When it comes to space, Beijing is not reverse engineering the technology and following in the footsteps of the United States and other developed states. China is making bold statements by achieving quite a few firsts while meeting nearly all of the self-imposed deadlines unlike its giant rival, NASA. And the race to infinity has barely started!

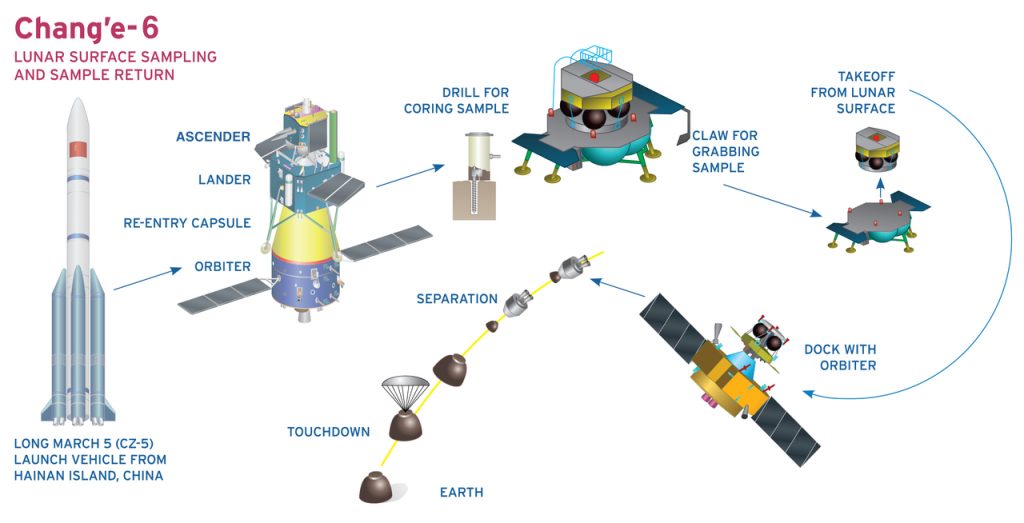

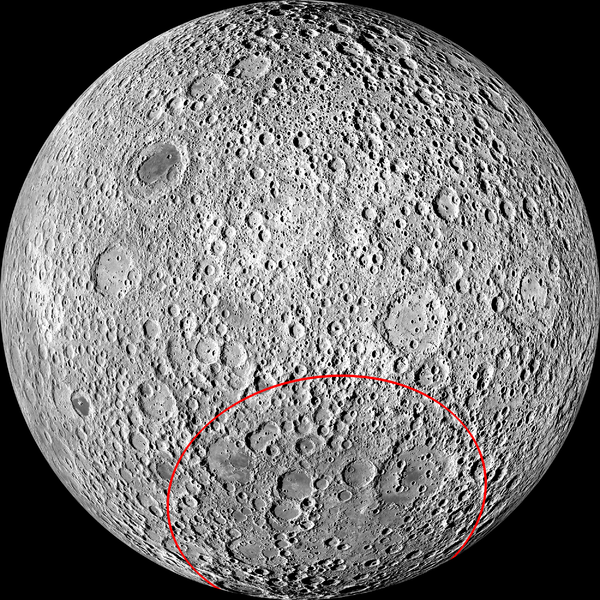

On May 3, the Change-6 spacecraft blasted off from Wenchang Space Launch Site in southern China to the dark-side of the moon for a 53-day mission. Last August, India become the fourth country to touch down near moon’s southern pole. However, the recent Chinese voyage goes a few steps further plans to grab samples containing material ejected from the lunar mantle, and then gather insight into the history of the universe. Beijing will study the sun’s poles from the far side of the moon besides looking for other exoplanets by setting up telescopes. Since the far side is geologically different with a thicker surface, China hopes to not only look for water and traces of the early universe but also find some rare metals and minerals. The notion of a moon-earth economic corridor has already been advanced.

The intricacy of the operation until the samples are delivered to Inner Mongolia is straight out of science fiction. A lander separated from the orbiter towards the southern edge of the Apollo crater on the far side of the moon where it is expected to land in early June. With a scoop and a drill, the lander will collect surface and subsurface materials from the South Pole-Aitken Basin, a crater 2,500 kilometers in diameter dating back to early times of the universe, which will then be blasted into lunar orbit by an ascender capsule. Due to communication issues, the operation will be completely automated or pre-programmed. Once in the moon’s orbit, the capsule will be captured by the orbiter, like a flying baseball ending up in a fielder’s glove but traveling at 1.68 kilometers per second. Once the samples reach the return module, another ordeal of re-entering the atmosphere awaits.

Typically, China like any other country will not share the entire details of its research pursuits, the materials and data gathered. For instance, experts discovered a rover attached to the lander in a picture of the Chang’e-6 spacecraft stack, which might be equipped with an infrared imaging spectrometer. After its return, soil samples in the module will be studied at various institutes in China. It is anybody’s guess if Beijing will share the moon dust with ESA, NASA, or other space powers. It took 2.5 years after its landing in 2019 to offer samples from the Chang’e-5 moon mission for global research.

Though US pressure is limiting European cooperation with China, the Chang’e-6 is carrying a scientific payload from France to detect radon outgassing from the moon’s surface, which will provide information on the lunar atmosphere. Sweden has sent the Negative Ions at the Lunar Surface (NILS), a device developed in Sweden with European Space Agency support, designed to study the impact of solar wind. Likewise, the Chinese Odyssey also has Pakistan’s ICUBE-Q cubesat aboard.

If all goes as planned with its space and lunar mission, China plans to send a crewed mission (three astronauts) to the moon in 2029 as part of the 80th anniversary celebrations of the People’s Republic of China. Building on earlier successes, Beijing plans to send Chang’e-7 in 2026 and Chang’e-8 before the high-prestige mission, including testing using lunar soil to 3D print bricks in preparation for setting up a crewed base.

Since 2019, Beijing has repeatedly proven its capability to shoot space-launch vehicles (SLVs) from floating barrages using cold pressurized gas with varying payload categories. With burgeoning competition amongst private launch companies, China is en route to industrializing the production of space launch vehicles and other paraphernalia for domestic and international partners’ needs. Alongside the United States and Russia, China is the third country to run its space station, named Tiangong, hosting three astronauts for periods of six months at a time. Operational since 2021, the China National Space Agency (CNSA) is scheduled to add two more modules, doubling the number of resident astronauts. Though smaller in size, the Chinese space base is quite capable of meeting the country’s ambitious goals. China’s Beidou constellation also parallels the United States’ GPS.

Half a century after the first moon landing, China can make its mark on the lunar surface with a super-heavy launch vehicle, a re-entry capsule and a lunar module to land and lift off. Beijing has achieved all this except for sending a crewed capsule.

Unlike Israel, India and Japan which enjoyed complete scientific and technological support from NASA, China does it on its own. Russia’s Roscosmos cannot successfully conduct a lunar landing due to Western sanctions since its Ukraine invasion.

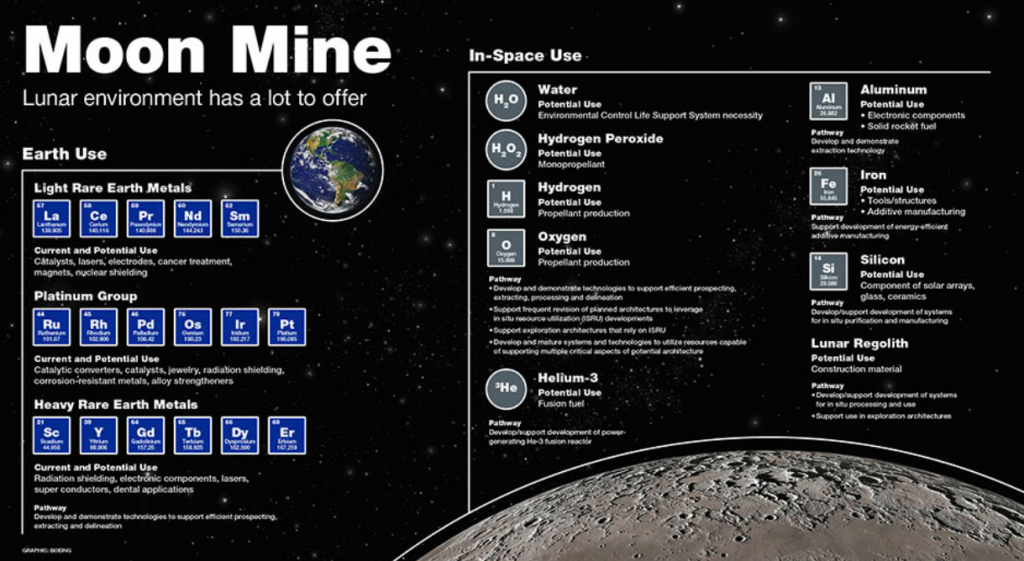

If China discovers water on the moon, the race will be in full gear to assess its volume, develop extraction methods in lunar gravity, exploitation and separation of hydrogen and oxygen to fuel rockets and for human consumption. Seismometers are already in place to study moonquakes and volcanoes and record the temperature of the soil. China has solely been conducting research on the far side of the moon since 2019.

The United States has long ignored the moon while developing knowledge and technologies to study Mars, asteroids and the history of the universe. NASA is to resume crewed missions in 2025, followed by China, the ESA and Japan. The discovery of water reservoirs on the lunar surface can start a new contest for celestial resources and military power.

Given the strategic significance and exponential financial cost, no base in space or planetary bodies will be for scientific research. The dual-use establishments mean a cut-throat contest for mineral exploration and military power.

Initiated in 2020, Washington’s Artemis Accords are bilateral arrangements between the US government and states to deliberate on the norms for outer space. Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain are amongst its members while China has been encouraging participation in the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) since 2023. Russia, Turkey, Egypt and Pakistan are among its members.

While the United States maintains numerous ground stations for deep space connectivity, it views with concern China’s Espacio Lejano Station, in Neuquen, Argentina. Beijing’s other two stations are located on its soil.

Amidst renewed global competition in outer space and unprecedented political polarization since the end of the Cold War, the United Nations working group on the legal issues mandated to propose principles for exploiting space resources by 2027 seems far from possible. Besides state actors, private entities are exploiting leaps in technology. The threat-perception matrix is further compounded by dual-use technologies while the Outer Space Treaty is already too outdated in its scope.

If the moon is a testing ground for Mars, it will also be a template for factories to build weapons and set up stations for jamming satellites to settle scores on Earth. The United States, Russia, China and India have already demonstrated the capability to shoot satellites from the ground. If one chooses to try the same from the moon, others will follow suit.

China’s current edge in the lunar domain is heating up superpower rivalries on Earth. If Beijing manages to extract soil samples from the lunar surface, it may well try the same on Mars too, a mission NASA and ESA have not been able to realize so far.