By the new wave of sanctions, the United States aims to dry up Iran’s revenue sources to increase its economic and societal pressure on the Iranian government, as well as, to isolate it within its geographic boundaries, and to force it to change its political and military policy in the Middle East. Perhaps, Tehran will not remain indifferent to the US sanctions and will adopt strategies and options to undermine them, especially those targeting its oil exports-Iran’s most important source of income- and those related to its trade exchange and financial transactions with other countries. Indeed, some of these strategies and options will be effective while others will be difficult despite having succeeded before.

After the US withdrawal from the nuclear deal in May 2018, the first set of sanctions-hit Iran in August 2018 and targeted vital products to the Iranian economy such as cars, metals, and carpets as well as US dollar financial transactions. On November 4, 2018, the second wave of US sanctions came into effect-targeting Iran’s oil buyers, ports, insurance services, and shipping to and from Iran, as well as, financial transactions to and from Iran’s central bank and its financial institutions. Accordingly, the Iranian decision-makers have been trying to reuse effective tactics used before and to develop new strategies to get around sanctions; however, the questions that arise – Will these tactics be successful in achieving their goals? Will these strategies be sufficient to make up for the negative impact of the US sanctions on Iran’s economy and society clearly reflected in its oil exports, growth rate, the balance of payments, prices, and the value of its local currency? On the other hand, will the United States economic dominance and its currency monopolizing 40% of global payments be sufficient for it to impose unilateral sanctions on Iran?[1]

This study aims to explore the strategies adopted by the Iranian government in response to the US sanctions including the tools used and their effectiveness in achieving Iran’s goals, as well as, to explore future Iranian reactions to these sanctions by extrapolating several scenarios.

The study is divided into five main parts and an appendix. The first part deals with Iran’s shift towards the East, particularly in economic cooperation with China, Russia, India, and North Korea. The second part handles the unknown destinations of Iran’s oil exports, its methods of evasion, and their effectiveness. In its third part, the study analyzes the European financial channel ‘Special Purpose Vehicle’ (SPV) and the SWIFT system, as well as, European motives and prospects in succeeding in their attempts to develop an alternative financial channel with Iran. The fourth part discusses Iran’s methods of evasion while the fifth part tries to extrapolate the best scenarios available to Iran to face the sanctions. Finally, the study provides a brief appendix of the most important current and expected economic indicators in Iran and a conclusion of the most important findings.

First: Improving economic and political cooperation with Eastern Countries

With increasing US pressure on the European countries and its companies to strengthen their embargo on Iran, the Iranian government is increasing its economic cooperation with its eastern allies such as China, Russia, India, and North Korea.

1. China

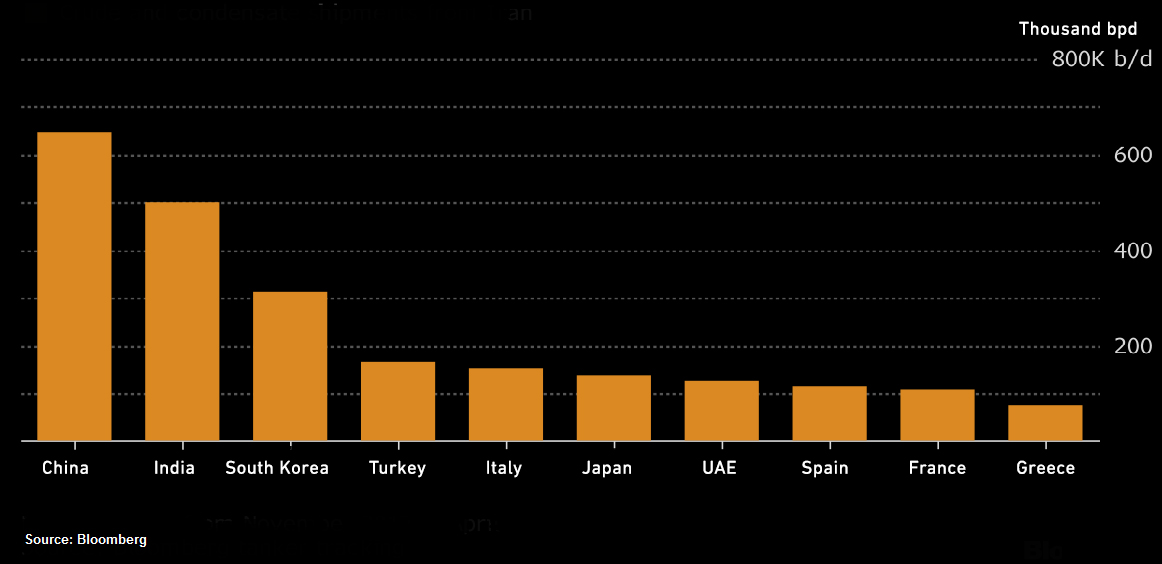

China has already opposed the unilateral US sanctions on Iran and has said that it recognizes sanctions, which are only imposed by the United Nations (UN) only.[2] For Iran, China is its most important potential savior in midst of the US embargo as it is Tehran’s first trading partner. In 2017, trade exchange between both countries registered 37 billion USD.[3] China is Iran’s biggest oil buyer and rejected US pressure to stop buying Iranian oil despite it pledging to not increase its oil imports in the future (more than 700 thousand barrels per day from January to May 2018, costing more than eight billion USD). However, after the departure of the French company Total from Iran, China has taken possession of its share in developing the Iranian South Pars gas field.

Figure 1: Major buyers of Iran’s oil from November 2017 to April 2018; China is ranked first

The question that arises here is- what are the outcomes of cooperation between both countries and can China save Iran’s economy from its current and possible future economic crises?

Beijing was the first destination for Iran’s Foreign Minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif after the US withdrawal from the nuclear deal. This highlights the importance of China to Iran at present and reflects the possibility of China-Iran trade and investment cooperation continuing under the condition of developing a secure financial transaction mechanism between the two countries.

There are several reasons behind potential China-Iran cooperation: in addition to providing a valuable resource and benefiting from Iran’s lower prices to attract buyers, China could use these relations with Iran as a pressuring card on the United States in the disputes between itself and Washington, particularly regarding tariffs, the South China Sea and the US withdrawal from the Paris Climate Convention. Daniel Glaser, an expert on sanctions in the US Department of Treasury believes that China will not change its long-term energy strategy due to a short-term diplomatic dispute[4] and that China will benefit greatly from Iran’s urgent need to be paid in credit rather than in cash or for its oil to be exchanged for Chinese products.

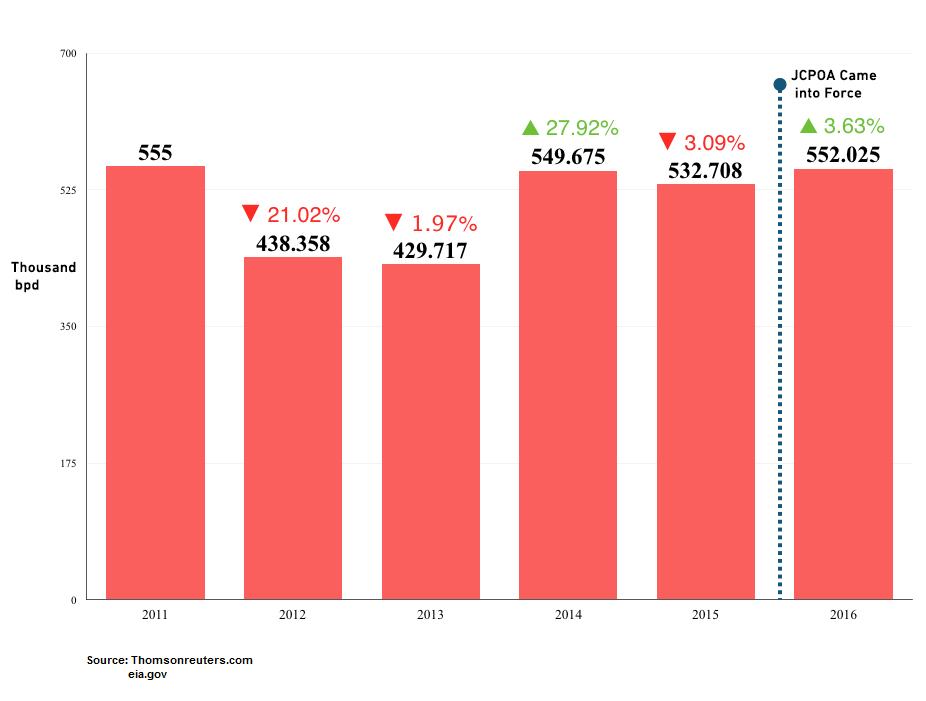

Figure 2: China’s imports of Iran’s crude oil from 2011-2016 (in thousand bpd)

With the first set of US sanctions, China reduced procurement of Iran’s oil by 20% in the period from May-August 2018. Despite China’s commitment to this policy being unclear[5], it is noted that this policy is same as the ones adopted in 2012 and 2013 before it re-increased its procurement even before the nuclear deal in 2015 as shown in the previous figure. This means that China is replicating the same scenario as it did before the nuclear deal.

The continuity of China-Iran trade and investment cooperation will play a major role in lessening, to a certain extent, the impact of sanctions on the Iranian economy as this will maintain financial flows for Iran’s general state budget and fill the void resulting from European investments departing Iran.[6] This cooperation applies more to governmental investment due to its low correlation with the US market while China’s private sector will be reluctant to invest due to its significant trade relations with the United States.

The statistics on the size of trade between the two countries are at odds when comparing Iranian and international sources. According to the statistics by the European Commission, the trade exchange rate between China and Iran increased from 20 billion dollars in 2015 to 27 billion dollars in 2017 while Iranian sources stated 37 billion dollars in the same year. In November 2018, the President of China-Iran Chamber of Commerce, Reza Hariri predicted trade rates between both sides would increase by the end of 2018 to reach 42 billion dollars because of hiked oil prices and the absence of alternatives to Iranian oil.

On the other hand, China’s increasing role in the Iranian economy could result in its monopolizing and influencing Iran’s decision-making due to Tehran’s limited options that might undermine its position in negotiations. Iran will also have to accept a lower quality in oil and industrial equipment technology from China compared to European technologies that would ultimately improve the competitiveness of Iranian products.

2. Russia

“The Russian President, Vladimir Putin decided to invest about 50 billion dollars in the Iranian oil and gas sector,” a statement made by the adviser to Iran’s Supreme Leader for International Affairs, Ali Akbar Velayati on July 13, 2018, after his meeting with Putin. Immediately on the same day, the Kremlin denied this statement when the Russian Oil Minister addressed the media and completely ignored Velayati’s statement, and provided Iran with the opportunity to purchase Russian products and services.[7]

In contrast to Iran’s expectations, Russia’s rebuttal revealed the weakness of economic cooperation between the two countries. In May 2017, Russia signed a barter agreement with Iran to supply it with Russian goods for 45 billion dollars a year in exchange for its oil, but the agreement has not been, fully or partially, implemented.

What can Russia actually do for Iran under the US sanctions?

During the period of international sanctions on Iran from 2007-2014, Russia-Iran cooperation was confined to limits of armament as specified under the sanctions regime and to some equipment and machinery. In 2014, trade exchange between the two countries registered 1.67 billion dollars[8] while in 2016 it registered about two billion dollars only.[9] Despite sanctions relief on Iran and an increase in political and military cooperation between the two countries concerning Middle East issues, trade cooperation remained limited during this period and showed no significant improvement post-sanctions relief in the aftermath of the nuclear deal. So, how would the size of trade between the two countries be boosted to 45 billion dollars after the reinstatement of US sanctions?

The Russian Minister of Oil commenting on Velayati’s visit, wishing Iran the opportunity to make business with Russia was as if he was saying, “If there was Russian support to Iran during sanctions, it would not be at the expense of Russian interests and its big companies.” The evidence of this is the withdrawal of the Russian state company, Rosneft from Iran after the re-imposition of US sanctions.

All in all, Iran will seek closer relations with Russia while Moscow has little to offer, other than in the defense and energy sectors.[10] The Russian economy has enough of its own worries stemming from US-European economic sanctions resulting from its interference in US elections and its annexation of the Ukrainian Crimea Peninsula. Therefore, the Russian government cannot trigger further economic pressures on itself or exacerbate differences further with the international community. In fact, the Russian economy does not have much to offer to Iran either by barter trade or in cash other than arms sales and some limited equipment and technology.

3. India

India’s position on the US sanctions on Iran has been notably cautious given its strategic relationship with Washington; however, oil is a powerful commodity binding India to Iran. Iran is India’s third-biggest supplier of oil after Iraq and Saudi Arabia, representing 10% of New Deli’s need for crude oil. In addition, Iran is an important logistics partner of India.

At the same time, India cannot undermine its common security and economic interests with the United States. It was in a confused position as it did not want to lose either side- the United States or Iran. At first, some unconfirmed statements were released concerning India’s intention to stop buying oil from Iran by November 2018 and then officially announced its recognition of international sanctions only imposed by the UN rather than unilateral sanctions.[11] It said it could reduce buying Iran’s oil by 50%, only if the United States provided it with the incentives to do this.[12] In August 2018, India decreased imports of Iran’s oil by half (400,000 bpd) before re-increasing them in September 2018.

India-Iran oil cooperation at lower rates is more likely to continue even after the expiry of US waivers on buying Iran’s oil.[13] So, how can New Delhi decline such an offer to buy Iran’s oil with free shipping and insurance, as well as, with lower payments?[14]

In addition to India’s willingness to diversify its energy sources, it has other important security and geopolitical goals. The Iranian port of Chabahar is important to India as it allows it to threaten Pakistan’s Karachi port and open new hydrocarbon markets in Iran, Afghanistan, and Central Asia by a network of railways.[15] Indeed, it seems that the United States is willing to allow India to complete this project and therefore, it excluded it from the sanctions targeting Iran’s energy sector.

4. North Korea

Tehran will seek to have North Korea, the US traditional rival, play a major role in marketing its oil in the upcoming stage as North Korea has a long experience in dealing with international sanctions and in smuggling oil with Russian and Chinese technical assistance.[16] Perhaps this is the message both Iran and North Korea wanted to convey during the visit of the North Korean Foreign Minister Ri Yong-ho to Tehran on August 7, 2018, when the first set of the US sanctions on Iran imposed.

In its Farsi version, the Russian Sputnik news agency reported from the South Korean researcher in Middle Eastern studies, Jiang Ji Hiang that Iran and North Korea have a long history of secret economic and military cooperation and that the best example of this cooperation is North Korea’s efforts in transferring weapons to the Houthis in Yemen with Iranian financial support as well as selling nuclear and missile technologies to Tehran. At the time Washington continues its simultaneous sanctions on North Korea and Iran, given this reality, the two countries are likely to step up cooperation with one another to lessen the impact of sanctions.

Second: The unknown destinations of Iran’s oil exports and effectiveness of pursuit

No less than 170,000 barrels or 11% of Iran’s exports of oil in the first two weeks of October went to unknown or undeclared destinations. Evidence has indicated that these shipments have gone to European countries such as Italy and to Asian countries such as India and Japan. In fact, Iran had adopted this policy before the second wave of the US sanctions came into effect. So, what prevents it from adopting the same policy either during the waiver period that the United States has granted to some countries (six months) or after it expires? How would this arise? This is what we will try to answer.

The decline of Iranian oil exports and a rise in unknown destinations

Asian countries were the biggest buyers of Iran’s oil before the reinstatement of the US sanctions. China was ranked first followed by India and South Korea and then European countries. Despite no change happening in this ranking after the re-imposition of sanctions, Iran’s oil exports declined to all buyers including its top purchasers.

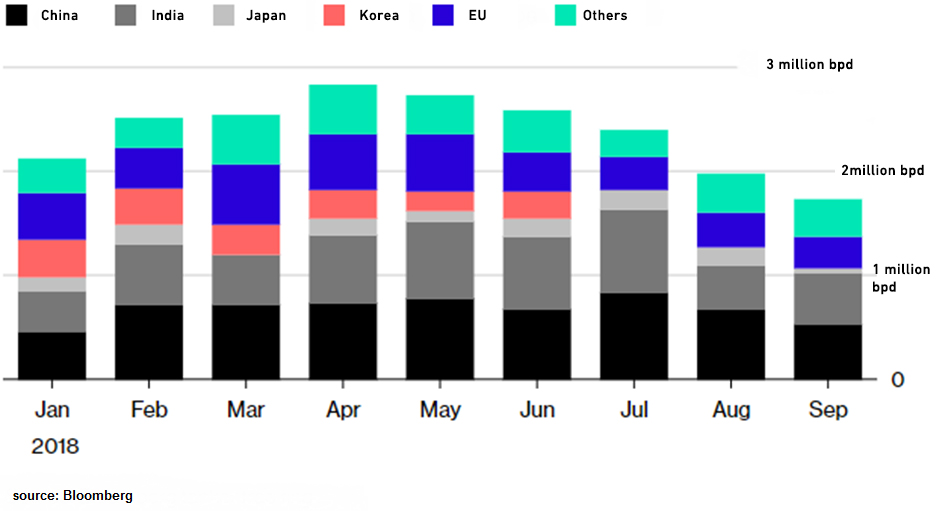

Figure 3: the Iranian crude oil buyers from January-September 2018 (in million bpd)

According to the previous chart and official records tracking Iran’s oil export destinations, starting from May (when the United States withdrew from the nuclear deal) to September 2018, Iran’s oil exports to China, India, Japan, Korea, and Europe declined, meaning that the majority of its biggest buyers had conceded to US pressure concerning this issue.

On the other hand, there was an increase in the unknown destinations of Iran’s oil exports in August and September 2018 (as shown in green on the chart). Some of these shipments might have been officially registered, but this does not deny the rise in such destinations compared to a decline of known destinations.

On October 7, 2018, Tanker Trackers[17] (independent online service that tracks and reports shipments and storage of crude oil all over the world) released a report, saying, “Iran is exporting large quantities of oil to more destinations than we thought.”[18]

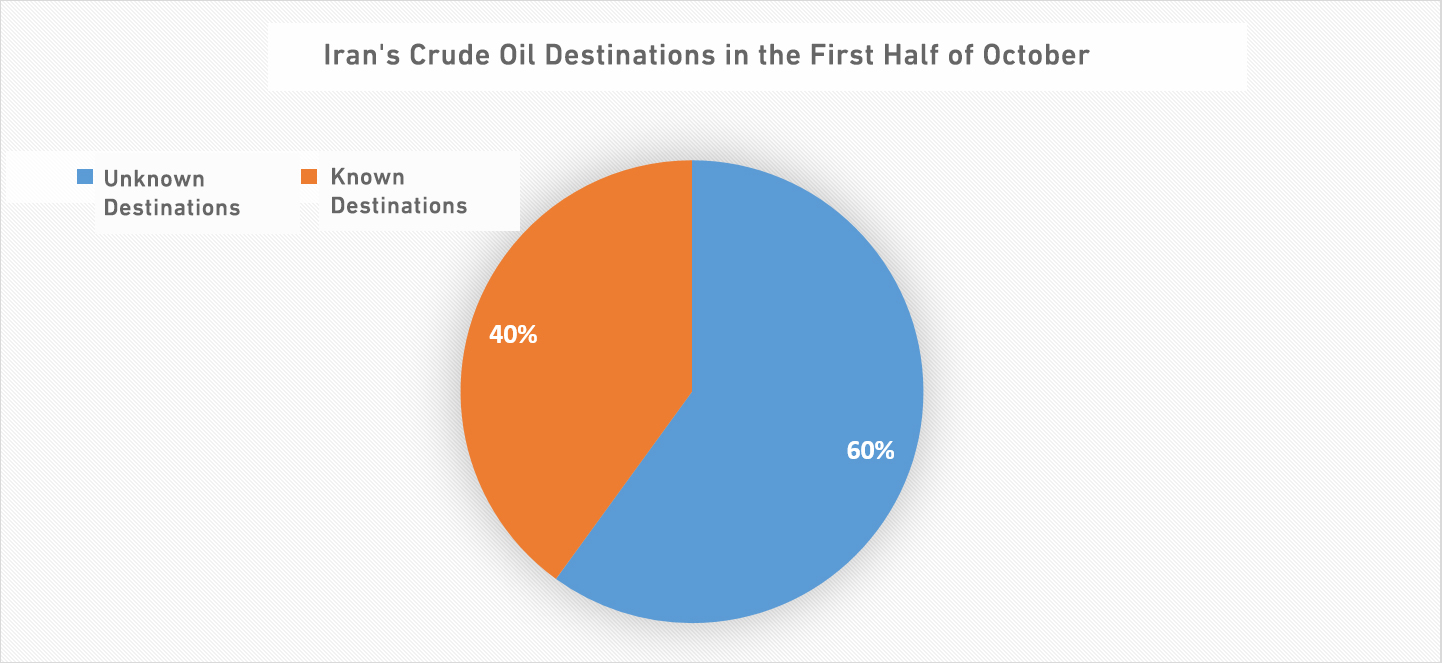

In the months of April and October 2018, we find that Iran’s oil exports declined by at least one million bpd. According to the official records of Tanker Trackers,[19]Iran was exporting about 2.5 bpd in April while in the first two weeks of October oil exports dropped to about 1.33 million bpd and to about 1.5 million bpd if we add the unknown destinations of these shipments, which means that about 11% of Iran’s total oil exports went to unknown destinations.

Figure 4: The rise of unknown destinations for Iran’s crude oil exports in the first half of October 2018

Prepared by: Unit of Economic Studies in the International Institute for Iranian Studies – Financial Times data

At the same time, other sources stated that Iran’s total exports of oil in the same period amounted to 2.2 million bpd,[20] that increases Iran’s exports to unknown destinations to 40% of its total exports of oil.[21]

Japan, for example, reduced oil imports from Iran significantly after the first set of US sanctions came into effect in August 2018. However, it received undeclared amounts of 1.39 million barrels of oil and natural gas from Iran in September 2018.[22]

Iranian methods in misleading international observers concerning its oil exports

No doubt, Iran has effective covert ways in selling its oil to make up for the decrease in its exports. Iranian oil tankers follow certain ways to avoid international tracking of their final destinations such as:

1. Turning off their AIS transponders to cloak their movement and final destinations[23] as well as concealing the identity of buyers to avoid US penalties. This tracking system tracks and reports the routes of commercial vessels under international maritime law. In fact, Iran used this technique effectively during the US-EU oil embargo in 2012.[24]

For example, oil tanker Suezmax Stark 1(used to transport Iran’s oil to India before the sanctions) left Iran with one million barrels of crude oil and headed east. Approximately 200 miles off the Indian eastern coast, the tanker turned off its tracking transponders and then reappeared in the same location after one week.[25]

The energy expert Alex Lawler says that final destinations of exports remain difficult to identify, despite tracking becoming easier than before due to satellite technology, but eventually, this issue needs “informed and involved” experts.[26] Perhaps, Lawler is referring to the experience of observers and the availability of informal private sources at Iranian ports and the potential destinations for Iran’s oil exports.

2. Concealment of shipments among other countries’ cargo: oil tanker YUFUSAN, flying the Panamanian flag was detected carrying oil from Iran last October and it then headed to Kuwait, carried Kuwaiti oil, and then headed to Japan. In appearance, this tanker carries Kuwaiti oil only, but, in fact, it carries bigger quantities of Iran’s oil.

3. Storing and then selling oil. Iran stores oil in giant tankers off its coasts and in large warehouses in other countries to be sold later. In 2014, during the previous sanctions before signing the nuclear deal Iran stored oil in the Chinese port of Dalian and then sold it to South Korean and Indian customers.[27] Iran also transports oil to customers’ ships in the open ocean far from its coasts so that buyers can avoid sanctions.[28]

Aerial photograph of six giant tankers with two million barrels capacity each, storing oil off the coast of Iran’s Kharge Island in mid-September 2018.

Source: Bloomberg.com.[29]

4. Other countries’ assistance: Iran’s major oil buyers such as China and India help Tehran technically to find new methods of deception in case old methods are detected as these countries need to diversify their sources of oil. In addition, Iran has offered price discounts to attract buyers and to transport oil to buyers in Iranian oil tankers (about 40 tankers) without additional charges.[30] Indeed, such cooperation would be covert to avoid any US financial sanctions as the case of India and Japan.

American procedures to curb Iran’s oil smuggling strategy

The United States has offered financial incentives to countries that reduce oil imports from Iran. Most major buyers have responded positively to these incentives. Nevertheless, what prevents these countries from lowering their imports only on paper to please the United States and continuing with importing Iran’s oil given the absence of an effective mechanism to prove sanction violations? some US officials believe this strategy is ineffective and that they can track Iranian tankers through Western spy satellites and other surveillance systems.[31]However, this depends on Washington’s seriousness and the use of its technologies.[32]

Peter Harrier, a former specialist in combating Iran’s threat at the US Department of State suggested, in an article published in the Foreign Policy Journal, an idea to impose sanctions on Iran’s oil prices rather than on the quantities it exported. [33]

Harrier suggested that Washington should at least temporarily refocus U.S. sanctions on the price that Iran gets for its oil, rather than the raw volume of oil exported. Under existing U.S. sanctions law, countries that want to qualify for the significant reduction exception must reduce the volumes of Iranian crude that they import—which has driven up prices, given that global supply is currently tight. A better strategy would be for Congress and the Trump administration to authorize a significant reduction for counties that reduce either the volume or the value of crude oil purchases.[34]The implementation of such a proposal could remove the need to track the unknown-destination Iran’s oil exports. In addition, this policy will be beneficial in maintaining global oil supplies.

Third: The European financial channel SPV and its opportunities for success

Due to the US financial embargo on Iran, the European Union (EU) is trying to create mechanisms to continue its trade and financial transactions to and from Iran. The most important of such mechanisms is the SPV.

What is the SPV?

On September 25, 2018, High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Federica Mogherini announced a new mechanism called the SPV to maintain trade with Iran under European law and to allow non-EU partners to join this channel. This system aims to continue the flow of financial transactions between Iran and other countries away from US sanctions[35] by using other currencies or conducting financial transactions away from the United States influence, including SWIFT.

This mechanism is expected to work as follows: for example, Iran sells oil to an Italian company and instead of receiving the sales value in cash, it is recorded in favour of Iran in its accounts. So, when Iran buys products from another European company, this company collects its cash value from the Italian company, meaning that transactions go from one European company to another without them being transferred directly to Iran.

The SPV to save the Iran nuclear deal is not yet clear.[36]The Spokesperson of the presidency of the Iranian parliament, Behrooz Nemati confidently said, “Western countries have promised to create mechanisms for financial transactions to and from Iran in parallel with the beginning of the second wave of US sanctions on November 4, 2018. Russia, China, and India will also be committed to this mechanism.” However, the Iranian media quoted European diplomats as saying that the launch of SPV would take months after imposition of sanctions on Iran.[37]

The European SWIFT and the United States influence

SWIFT is a global financial network based in Belgium. It links banks and financial institutions using digital codes all over the world. More than 11,000 financial institutions in more than 200 countries are linked to this system.[38] So far, the removal of Iran from SWIFT has not been listed on the US sanctions, but there is internal pressure in the United States to ban Iran from using SWIFT.[39] In the first place, SWIFT follows EU resolutions- as was the case during Iran’s ban in 2012- but it acts under Belgium law. The United States does not have a majority on SWIFT’s board of directors, but it can impose sanctions on banks integrated within SWIFT and that deal with Iran’s financial institutions.[40] For example, in February 2012, the United States blocked the transfer of 26,000 dollars from Denmark to Germany to complete a trade deal linked to Cuba that is subject to US sanctions.

The European motives to create an alternative financial transaction channel with Iran

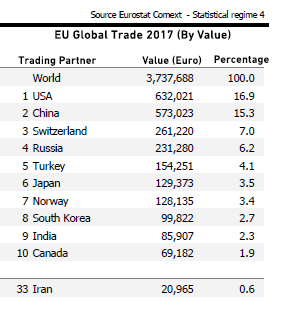

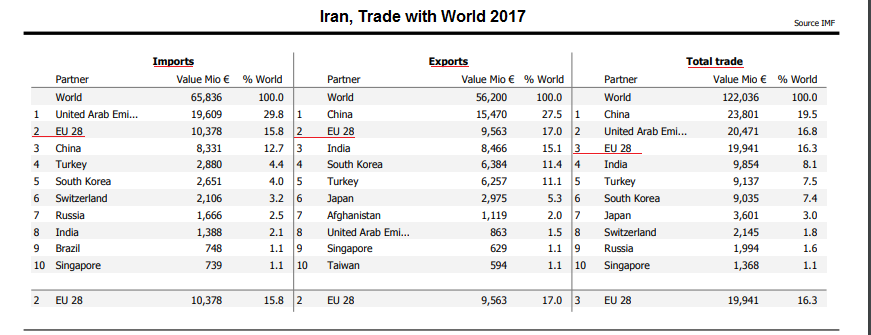

In 2017, before the United States withdrawal from the nuclear deal, trade exchange between the EU and Iran registered 21 billion Euros; more than 50% were EU manufacturing exports to Iran. However, this number represents only 0.6% of the European trade balance with the world. Iran is ranked as the 33rd partner to Europe while the United States and China lead with almost 17% and 15% respectively as shown in the following figure:

Figure 5: EU trade balance with the outside world in 2017

The EU motive for saving the nuclear deal seems to be its willingness to achieve certain political and security goals rather than the importance of Iran’s oil and market to its economy. Indeed, the EU strives to maintain its national security, the security of its regional allies, stand against US policies ignoring its political and economic standing, and lower the US US dollar’s dominance on world trade.[41] Also, the EU seeks greater financial and banking independence by creating alternative financial transaction systems away from volatile US policies as stated by the German Foreign Minister, Heiko Maas in an article in the German newspaper Handelsblatt.[42]However, this does not deny the fact that the Iranian market was full of promising opportunities for European companies after signing the nuclear deal, but these opportunities have been lost due to the US withdrawal from the nuclear pact.

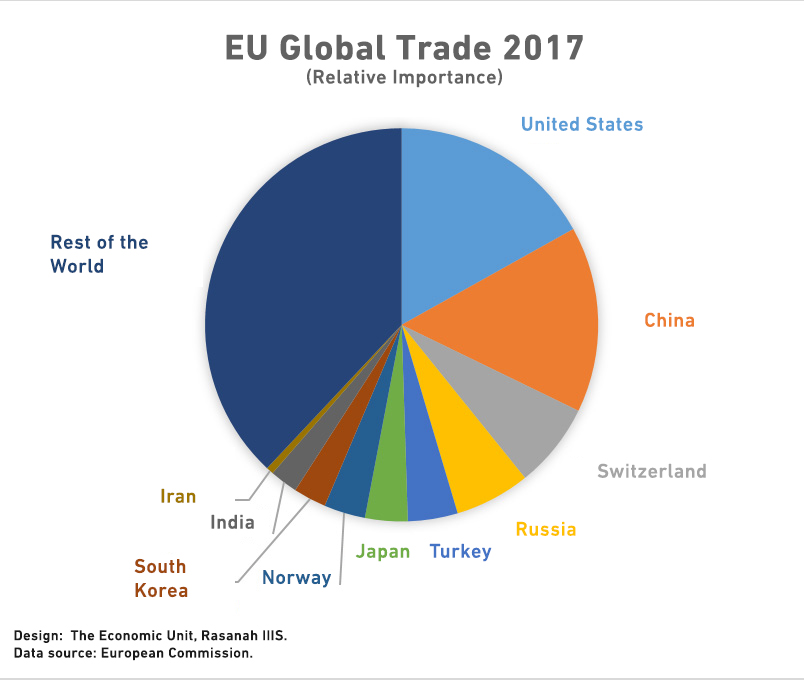

Iran is the biggest beneficiary of continuing its financial and trade channels with the EU, which is evident by Mogherini’s statement, “Trade between Iran and the EU is a fundamental aspect of Iran’s right to receive economic advantages in exchange of its commitment to nuclear obligations.”[43] The following table shows the economic importance of the EU to Iran. The EU is Iran’s third biggest trade partner with nearly 16% of Iran’s total trade volume with the world after China and the UAE (this ranking might change in the future after the UAE announced its compliance with the US sanctions on Iran and measures it will undertake to stop money laundering and terrorist funding across its territory).

Table 1: Iran’s trade balance with the outside world in 2017

*In million Euro

Euro = 1.14 dollar

Source: the European Commission, and the International Monetary Fund

How successful is the European Mechanism?

If the European channel succeeds in solving the problem of financial transactions to and from Iran, it will likely be valid for small European companies and possibly medium-sized companies rather than larger companies that have stakes in the US market and. are linked to the American Capital Markets or Markets chaired by American boards of directors. For these companies, the risk of being banned from the US markets is greater than the potential losses of negating their trade relations with Iran,[44] as seen by the withdrawal of Total, Peugeot, Siemens, and Airbus from Iran’s market.

Professor Richard Nephew at the University of Columbia believes the European channel is an innovative way to solve one problem: financial transactions with Iran with the refusal of banks. However, these sanctions do not only target financial transactions, but also goods and their movement. Therefore, the European channel is unlikely to be suitable for large-scale businesses to and from Iran or to invest in Iran.[45] If this is the case, trade deals with Iran will shift from big companies having advanced technologies and considerable capital to small and medium-sized ones with limited potential. This will negatively impact Iran’s means of production, operating rates, domestic production, availability and competitiveness of its goods.

Fourth: Means to circumvent the US sanctions

In addition to the aforementioned Iranian responses to US sanctions, several Iranian methods have not been disclosed yet. Some of these methods are known while others are still secret that have been prepared by Iran’s government since last year and are gradually being implemented in the oil, petrochemicals, and cars industries. This was stated by Sa’eed Bastani, a member of the industries and minerals committee in the Iranian Parliament.[46]One known method has been to create an internal energy stock exchange by Iran’s Ministry of Energy to sell oil to the private sector at lower than world prices with long-term payment plans. In this case, buyers are responsible for selling crude oil in their own way.

Iran uses other techniques to satisfy its needs such as front companies that belong to charities and religious associations, foreign bank accounts using forged passports of non-Iranian nationalities, using the exemption of food and medicinal imports from the US sanctions to establish companies in China or Africa for money laundering purposes and to import goods, as well as, flying the flags of small countries such as Tuvalu on Iranian oil tankers for smuggling, and signing agreements to exchange oil for local currencies.[47]

In fact, Iran uses various methods to circumvent sanctions. Once a method fails, the Iranian government creates a new one. Therefore, the United States is looking for ways to face Iran’s methods of getting around its sanctions, but it might succeed or not. However, it is notable that most of these methods are more expensive for Iran than direct and legal methods.

Selling oil through the low road [illegitimate], although better than nothing, requires offering discounts to convince buyers to bear the risk of making business with Tehran. In fact, the Iranian government bears higher costs resulting from oil transportation and increasing internal corruption. The fraud committed by Iran’s Oil Ministry via the Iranian mediator, Babik Zanjani is an example of the high cost paid by Iran’s people and its economy as a result of such illegal methods.

Fifth: Scenarios of Iran’s future resistance in the face of US sanctions

No doubt, the latest US sanctions have impacted negatively on Iran’s people and its economy. However, it is important to not ignore the fact that all forty-year-old and younger Iranians have witnessed successive international sanctions on their country; American, European, international sanctions, and sometimes simultaneously. This means that a big segment of the Iranian people- same as the Iranian government- are used to living bitterly under sanctions.

This does not necessarily mean that the same scenarios will be repeated after the imposition of the new sanctions as if nothing new would have happened. Each time the sanctions have led to different developments and the political systems’ inflexibility has led to the slow realization of the nature of these developments resulting in quick and unexpected consequences. In the following lines, we will discuss three future scenarios of Iran’s resistance in the face of US sanctions.

Scenario One: Iran’s long-standing resistance to US sanctions

Resistance here does not mean to prevent damage caused by US sanctions, but to minimize the damage as much as possible without changing the Iranian government’s position towards the United States.

To attain this scenario, Iran has to be able to take effective measures to stand against the US sanctions, such as to maintain the flow of governmental revenues necessary to run the country, to continue exporting its crude oil, and to stop the draining of foreign currency by boosting its non-oil exports and limiting its consumption commodity imports.

Externally, the support of major allies such as China and the EU should continue to provide Iran with raw materials, spare parts, intermediate and final goods, in addition to creating effective financial channels for trade exchange with Tehran. The Iranian government is betting on the American elections and a change in the current US administration, with the hope that the new administration restores the nuclear deal.

In fact, this scenario is linked to the stability of Iran’s internal conditions and Iranians’ being able to adapt their living conditions.

The Iranian Parliament Research Center released a report saying that the most optimistic scenario outweighed the possibility of an economic recession by 0.5% by the end of 2018, 3.8% by 2019, and a downturn in Iran’s critical industries such as automobiles by 22.5%.[48]

Scenario Two: popular revolutions and state’s failure

This scenario is likely to result from economic breakdown due to US sanctions. However, it is an unrealistic scenario, despite being frequently touted by media, for reasons explained in a previous study by the International Institute for Iranian Studies in August 2018.[49]

However, there is a critical factor- usually quick and surprising- to be taken into consideration. Half of Iran’s society is young and most of them are highly educated and unemployment among university graduates is 33%-one out of three. When these conditions meet with the harsh living conditions, psychological and societal crises increase, which would crowd out investments, and increase the pressure on the Iranian youth; a situation similar to that of the Arab Spring revolutions despite the strength of regimes at that time.

Scenario Three: interim resistance while opening the door for negotiations

The Iranian decision-makers continue to resist the US sanctions and temporarily reject making concessions for a few months after the US waiver given to some countries to import Iran’s oil ends. The Iranian government would be obliged, at some point, to negotiate with the United States by making concessions to preserve its very existence as a state.

During this interim period, the Iranian government would be using sanctions to unify its internal front to achieve political gains and to express its rejection of US demands and to show the effectiveness of its resistance, especially during the period of the US waivers to right major buyers of Iran’s oil such as China, India, Turkey, and Japan.

As economic and societal strangulation increases, Iran would resort to negotiations with the United States to revoke or lower sanctions in exchange for complying with some or all US demands, particularly those related to curbing its ballistic missile program and its regional military role. In fact, curbing Iran’s regional role is still out of reach as this is an integral part of Iran’s doctrine and foreign policy under the pretext of “defending the vulnerable” as stated in the Iranian constitution.

In a workshop organized by the International Institute for Iranian Studies concerning future of US-Iran relations in Riyadh, Norman Roule, a former US principal intelligence community official responsible for overseeing all aspects of national intelligence policy and activities related to Iran, said, “The US administration will continue its imposition of economic sanctions on Iran; hopefully, to bring the Iranian government to the table of negotiations directly or indirectly through the Iranian people.”[50]

This scenario might change the position of Iran’s allies in exchange for settling outstanding issues with the United States such as Russia bargaining to lower US-Europe sanctions imposed on it due to its occupation of the Ukrainian Crimea, or China maneuvering for the US to lift trade restrictions on its exports to the United States.[51] Or, the pressure of the European interest groups on their governments to change their supportive positions towards Iran and exploit the Iranian involvement in terrorist activities and assassination of Iranian opponents in Europe.

The Most Likely Scenario

The scenario of Iran’s long-term resistance to US sanctions is ineffective. Usually, people and governments as well, cannot afford the consequences of economic sanctions for too long, especially if they heavily rely on imports. In fact, this was Iran’s primary motive for negotiations with the West in 2015 that ended up by signing the nuclear deal after three years of an intense embargo on Tehran. The scenario of the Iranian government collapsing due to economic recession is ruled out. However, the possibility of a sudden youth-led popular uprising challenging the iron-fisted security machinery cannot be excluded.

The most probable scenario is the third one (interim resistance while opening the door for negotiations). The duration of interim resistance will be determined by stability or change in the of position of Iran’s major allies, the effectiveness of its measures in the face of sanctions, and Tehran arbitrary betting on the change of the US administration in the upcoming elections in 2020 in the hope of it adopting a less hardline policy on Tehran.

Nevertheless, no matter how long it takes, this period will probably not be enough to make up for the negative impact of sanctions on foreign investment, growth, production, employment, and inflation, as well as, the pessimism that would hang over Iran’s future trade deals with the outside world.

A careful consideration of the economic indicators gives a clear understanding of Iran’s current and future challenges that will be listed in the appendix of this study.

Appendix: Iran’s current and future economic indicators

Iranian economic indicators since the implementation of the nuclear deal in 2015 until the imposition of the first wave of US sanctions on August 6, 2018, were analyzed in a previous study published by the International Institute for Iranian Studies in August 2018.[52]Today, in this study, and after the implementation of the second set of US sanctions, we will briefly address the developments and indicators necessary to gain insight on Iran’s current economic conditions and try to forecast the future after the implementation of the two phases of US sanctions on Tehran.

1. The real GDP grew by 2.5% in the second quarter of 2018. In November 2018, the British “The Economist” published a report predicting growth to decline and register -4.6% by the end of the fourth quarter of 2018, which means Iran falling into a recession until 2019. This is to be influenced by a decline of the added-value of Iran’s GDP economic sectors in 2018 such as the services sector (about -14%) and the industrial sector (-0.7%). In addition, Iran’s engines of economic growth declined; total fixed investments (-1%), private consumption expenditures (-1%), goods and services exports (-13.5%), and goods and services imports including production imports (-22%).[53]

2. The current net trade balance shows a 31.4 billion dollars surplus by the end of 2018 to fall to about 14 billion dollars in 2019. This constant surplus in the balance of payments is attributed to a hiked oil price, a decline in consumer and investment imports, and the devaluation of Iran’s local currency that impacted positively on the increase of its non-oil exports. In reality, this surplus will act to absorb the shock of financial crises in Iran in the short run.

3. Consumer prices rose by 24.5% in the third quarter of 2018 on an annual basis[54] while the International Monetary Fund expected inflation to register 40% by the end of 2018.[55]

4. Unemployment registered 12.7% in 2018 according to the Economist, but Iranian data recorded lower figures.

5. Budget deficit registered 1.8% of the GDP in the fiscal year 2017/2018 and is expected to rise to 2.8% in 2018/2019 because of a decline in government revenues and its plans to increase financial support to avoid popular protests once again in the country.[56] In fact, the actual budget deficit increased by 126% to register 2.6 billion dollars in six months from March to September 2018.[57]

6. The Iranian currency (toman) devalued in the free market from 5500 tomans to the US dollar in April to about 14,000 in November. The Iranian government was obliged to sell the dollar at a subsidized rate to buyers of some essential products such as food and medicine, exerting pressure on Iran’s reserves of foreign currency that amounts to 108 billion dollars covering thirteen months of imports compared to an estimation of 133 billion dollars in 2016.[58]

Conclusion

Iran is subject to harsh sanctions aimed at besieging its government, drying up its revenue sources, and increasing pressures on it to force it to change its political and military strategies in the Middle East. Obviously, the Iranian government will not remain indifferent to US sanctions and will adopt certain strategies and options some of which might be effective, others less effective, while others will be useless:

– The first option is to maintain economic and political cooperation with eastern countries such as China, India, Russia and, North Korea. China will be Iran’s most important trade and investment partner to fill the vacuum resulting from the outflow of European investments. Iran’s dependence on China as well as its domination over local activities in Iran will increase especially Chinese companies that have no relations with US markets. In return, Iran will have to accept a lower quality of goods and technologies compared to that provided European industries, while China’s willingness to diversify its oil resources will drive it to buy oil from Iran even under US sanctions.

Since the beginning, India has been reluctant to comply with the US sanctions and it seems to remain so, given India’s geopolitical goals such as completing its development of the Iranian port of Chabahar, opening itself to new markets in Central Asia, and gaining access to Turkmenistan’s gas through Iranian territory. Iran will also resort to North Korea to replicate its techniques in smuggling oil under US sanctions while Russia has little to offer to Iran to lower the impact of economic sanctions except political support and military equipment.

– The second option for Iran is to use diversionary tactics to continue exporting and selling oil under sanctions. Hence, decreasing Iran’s exports to zero, as the US administration seeks, is far from being achieved. However, it is certain that the size of Iran’s exports will not be the same as it was before the imposition of the two sets of sanctions- in August and November 2018. These sanctions will make oil exports more difficult to sustain not only because of financial sanctions imposed on buyers but also because of removing Iran from the international financial system, especially if the United States succeeds in excluding Iran from SWIFT. In addition, the United States can use techniques to control oil smuggling and impose financial sanctions on buyers, utilizing Western spy satellites- in case sanctions are taken seriously- or changing the sanctions strategy.

– The third option is to rely on the EU in finding a legal way to maintain a flow of international financial transactions and avoid the US sanctions. So far, Europe has not implemented this strategy yet, but it insists on making it come true. In fact, Europe is not in dire need for trade with Iran, but to show political and financial independence from the US administration. If Europe succeeds in activating the SPV mechanism, Iran will benefit from financial transactions, particularly with European small and medium-sized enterprises. In return, Iran will be deprived of big European companies investing that have large financial and technological potentials due to their trade relations with the US.

– In addition to the three aforementioned options, Iran has more tactics and tricks to get around the sanctions; whenever a method is exposed, these tactics change. However, most of them- if not all- are more costly for the Iranian people and the economy than direct and legal methods.

After going over the three future scenarios for Iran’s resistance to US sanctions, the most probable scenario, according to evidence, is the Iranian interim resistance to US sanctions after the expiry of the US waivers provided to eight countries. By the time, the US economic and societal pressures- as explained in the appendix of this study- will drive the Iranian government to open the door for mediation or direct negotiations with the United States and to make concessions to lift or lessen sanctions that threaten its survival. The duration of this interim resistance will be determined by the effectiveness of Iran’s measures in the face of the sanctions and on the stability or change in position of Iran allies’.