Following the lifting of Western sanctions on Iran’s primary source of income, foreign oil, and gas exports, and the Tehran government is currently expending massive efforts to expand its oil and gas sales to overseas markets. It needs to do this in order to generate the funds to escape its current economic crisis, reduce its budget deficit and lower its domestic and foreign debt, which are growing rapidly as a result of its involvement in regional conflicts and aggravating its existing serious domestic problems. These include soaring unemployment rates which recently hit 8 million jobless, in addition to high prices for basic goods endured by Iran’s citizens for years, which have continued even after the lifting of Western sanctions.

Following an agreement concluded with the Western powers in November 2015 easing the ban on the overseas export of Iranian oil and gas, which came into effect in January of this year, the US and Western European powers imposed a variety of economic sanctions on Iran over its nuclear activities. As a result of this, Iran’s oil exports have been curtailed to one million barrels per day (BPD), the same level as since 2012, although oil exports before the ban were estimated at 2.3 million (BPD). Domestically Iran consumes around two million BPD, with current daily production rates of approximately 3, 800,000 (BPD), although the country is striving to return to the pre-ban production and export levels.

This study addresses three main themes: the first section shows the primary importers of Iranian oil, while the second deals with the leading importers of Iranian gas. The study concludes with a display and analysis of the future of the Iranian oil and gas exports.

» First: the primary importers of Iranian oil

China, India, Japan and South Korea are currently the largest importers respectively of Iranian crude oil, with most of the market for Iran’s crude oil exports concentrated in Asia, although Tehran is now bidding to open new markets in the countries of Eastern Europe and neighboring nations, and to regain lost markets in some African countries following the lifting of international sanctions.

Levels of the aforementioned Iranian crude oil exports to most countries have varied over the years. To illustrate the disparity between the imports of each country we will compare the level of the current imports after the lifting of the international embargo to those before last year’s lifting of restrictions on Iran’s oil exports. We will also include the figures for the client nations’ highest and lowest import levels of Iranian crude oil during the past five years, starting in 2012 [1], as well as discussing and analyzing these countries in descending order, from the largest to the smallest importer of Iranian oil.

China is by far the largest importer of Iranian oil. In the past five years, it has become the second largest oil importer in the world after the United States, although the size of its imports fell to 671,200 (BPD) during April 2016, compared to the volume of imports of 707,400 (BPD) in April 2015. This meant a percentage of the decline of over 5.1% in a one-year period. China recorded its largest monthly imports of Iranian oil in April 2014 when it imported an average of around 800,000 (BPD) and its smallest in October 2013 when it imported around 250,000 (BPD).

India has become the second largest importer of Iranian oil in Asia over the last five years, with its imports of Iranian oil rising dramatically, by 48.8 percent since the beginning of 2016 to reach around 393, 00 (BPD) in April 2016, compared to 264,100 barrels in April 2015. India’s imports of Iranian oil reached their highest rate in five years in March 2016, when they rose to 506,100 (BPD), although they’ve fluctuated between 100,000 and 400,000 (BPD) over the five-year period. India recorded its lowest monthly imports of Iranian oil for this period in July 2013, when it imported only 35,500 (BPD).

Japan is currently the third-largest importer of Iranian oil, although its imports fell sharply in April 2016 by 71.8% to 19,200 (BPD) compared to 68,300 (BPD) in April 2015, following a 10.7 percent rise in January 2016 compared to January 2015, recording imports of 194,100 (BPD) in 2016 compared to 175,300 (BPD) in 2015.

It’s noteworthy that over the past five years, Japanese imports of Iranian oil always seem to peak in January and hit their lowest annual point in April, with the highest monthly import levels, 339,000 (BPD), recorded in January 2012, while the lowest monthly figure was seen in April 2013, when it imported mere 7, 500 (BPD).

Imports of Iranian oil by South Korea, the fourth-largest importer of Iranian oil, have risen sharply over the past year, recording an 88 percent increase from 126,000 (BPD) in April 2015 to 237,100 (BPD) in April 2016. South Korea saw its highest monthly levels of imports of Iranian oil within the past five years in February 2014 and February 2016 when it imported 293,000 (BPD) and 282,200 (BPD) respectively. The lowest levels of South Korean imports of Iranian oil were recorded in August 2013 when a mere 63,500 (BPD) were imported.

Source: Reuters Graphics. 2016.Asia’s Iranian crude oil imports

By analyzing the previous figures, we confirm that China and India were the largest importers of Iranian crude oil, respectively, with imports by both nations rising significantly in April 2014. India’s imports continued to increase in subsequent years up to the present, although China’s imports curve, like Japan’s, then declined up to April 2016, reducing their imports of Iranian oil while India’s and South Korea’s import levels grew in the same period.

It is important to note that India and South Korea have seen the most rapid increase in the volume of Iranian crude oil imports since April 2013, with the levels of both countries’ imports continuing to increase steadily in 2016. This reflects the strong cooperation between them and Iran following the lifting of international sanctions on the Tehran regime, with this growth shown most clearly by the 88 percent increase in South Korea’s imports of Iranian oil between April 2015 and April 2016.

Following the lifting of the international sanctions and as part of its quest to overcome its endless financial crises, Iran is currently pursuing oil contract agreements with the European giants in the field of oil discovery and export, such as British Petroleum, and Italian ENI, the multinational oil and gas company which were unable to trade with Iran before the sanctions were lifted.

Tehran is also attempting to expand into new oil markets in Eastern Europe such as Hungary, Poland, Bosnia- Herzegovina, Serbia, the Czech Republic, and Croatia, as well as into Southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia, and to compete with leading international oil exporters by selling oil at below world prices.

The central role played by Iran in the African continent should also be noted, with the theocratic regime taking advantage of its infiltration in some countries of the continent under the cloak of religious and nationalist slogans, to build business partnerships with nations in all parts of Africa, north, south, east, and west. In the area of energy, South Africa, and Kenya were the main allies of Iran in Africa before the imposition of international sanctions. South Africa was attaining 30 percent of its oil imports from Iran until 2012, at a rate of 70,000 (BPD), but the sanctions dramatically decreased import levels.

Iran is now seeking to restore its previous role in South Africa after the lifting of the sanctions, which impeded the work of Iranian companies in Africa in several sectors, with the most prominent example of this being Iran’s 49 percent ownership stake in South Africa’s ‘MTN’ telecommunications and mobile phone company. [ 2]

In a step indicating both countries’ eagerness to restore economic ties, South African President Jacob Zuma visited Tehran in April for three days, signing 200 cooperation agreements during his trip in the areas of oil and gas, financial services, and other areas of joint cooperation between the two countries. [ 3]

Kenya is another African country where Iran is seeking to restore its previous strong business relations following the lifting of international sanctions, with the two countries signing an agreement for Iran to supply 80,000 (BPD) of crude oil in 2012, a deal that was canceled following the imposition of Western sanctions shortly afterward. Iran has claimed that it had resumed exporting natural gas to Kenya via Marin tankers in May, although the Kenyan Petroleum Authority subsequently denied these claims [ 4]. Be this as it may, the claims do not negate the trend of Iran reviving relations and strengthening its existing presence in the African energy market as quickly as possible.

» Second: importers of Iranian gas

While Iran occupies the second place after Russia in terms of global reserves of natural gas, it has not yet begun extensive exports of gas for several reasons; these include rising domestic demand for gas given Iran’s status as one of the largest consumers of natural gas worldwide, and the nation’s lack of advanced technology to access the gas deposits, exacerbated by the economic sanctions imposed by Western nations.

Domestically, Iran ranked as the third largest domestic consumer of natural gas globally in 2015, when it consumed around 150 billion cubic meters of gas. The potential revenue from natural gas exports has not been considered sufficiently lucrative to justify the high cost of extraction by the regime previously, with the amount earned from selling the gas less than the costs involved in extracting it.

For this reason, Iran has not counted on gas exports as a revenue stream, with its income from natural gas exports accounting for less than four percent of the funds generated by the country’s exports in 2010 compared to the 78 percent of the market accounted by for oil exports, according to US Energy Information Administration figures. (EIA) [5].

Despite this, Iran has signed agreements with several countries, including neighboring nations, for the export of natural gas, via pipelines to nearby countries and via liquefied gas shipments to more distant overseas customers, although most of these agreements have not yet entered into force. Following the lifting of the Western sanctions Iran is seeking to emerge as a player in the global gas markets and to attract energy technology, especially liquefied natural gas technology with the help of Western developed countries, to expand the export of energy as a means of helping to pay off the nation’s economic debts domestically and overseas. The Tehran regime is also seeking to resume work on the creation of a liquefied gas production facility in Iran which was suspended following the imposition of Western sanctions which prevented investment and advanced technology from entering and developing the country’s liquefied gas sector.

In order for Iran to be capable of exporting effectively, however, it needs to first fulfill growing domestic demands, which are expected to increase to 190 billion cubic meters (6.7 billion cubic feet) in 2025 and secondly to rapidly increase production levels and rates in order to keep up with projected future demand. Rahenama Moses, an analyst with the ‘Energy Aspects’ Research Center in London, believes that any significant increase in production rates will take at least three years for Iran to achieve. [5], especially in light of the rate of development of the South ‘Pars’ field, one of the largest gas fields in Iran or globally, whose development took longer than expected.

» Current Iranian Gas Importers

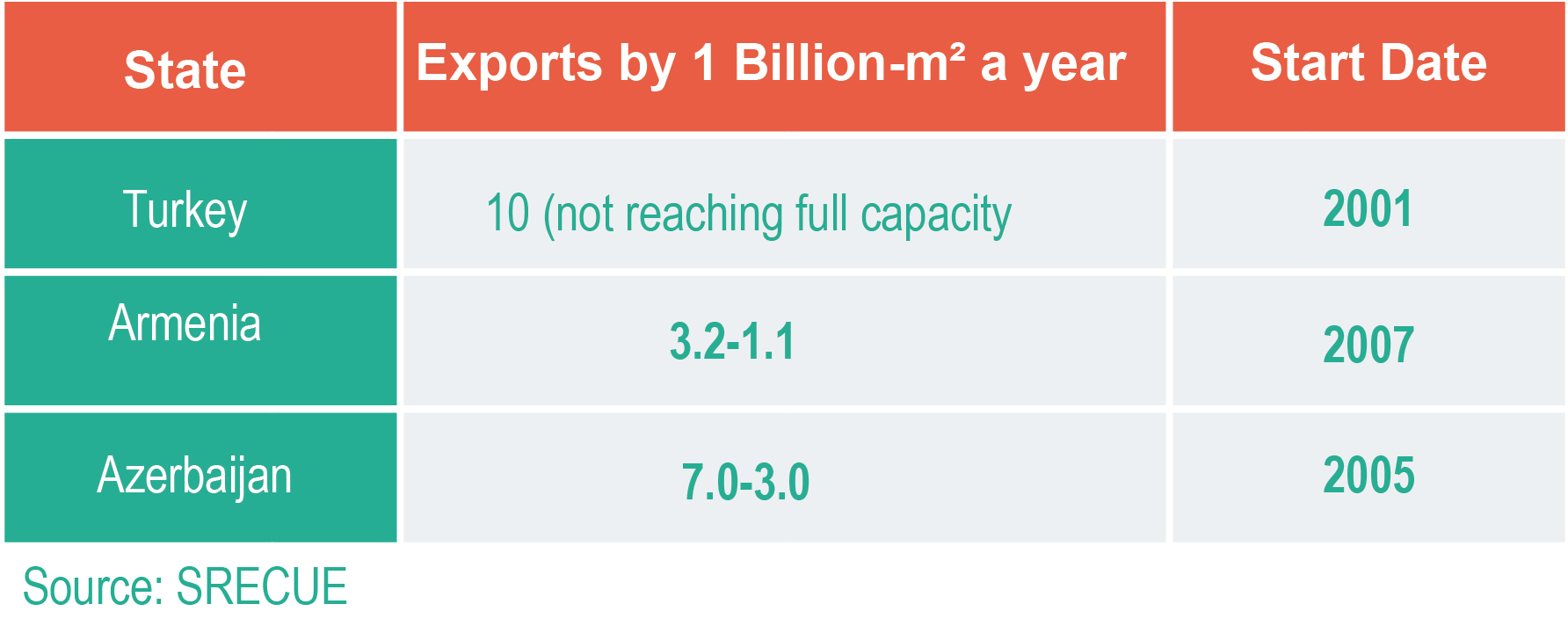

Iran is a weak country in terms of overseas gas export, especially given the relatively small exports compared to the massive size of the reserves, an estimated 1,200 trillion cubic feet, or 18% of world reserves. The most prominent importers of Iranian natural gas are neighboring countries such as Turkey and Armenia and Azerbaijan, where Iran has constructed pipelines to transport the natural gas directly.

Turkey is the largest importer of current Iranian gas via pipelines between the two countries, importing what was originally projected to be 10 billion square meters annually under the terms of a 2001 agreement between the two countries. Iran’s failure to reach the promised capacity means that Turkey has taken Iran to an international court to sue over non-compliance with the agreement’s terms.

Armenia and Azerbaijan, meanwhile, each import far smaller amounts of Iranian gas, with Armenia importing between 1.1 and 2.3 billion square meters annually since 2007, while Azerbaijan has been importing between 0.3 and 0.7 billion square meters per year since 2005.

Iran agreements for future gas supplies

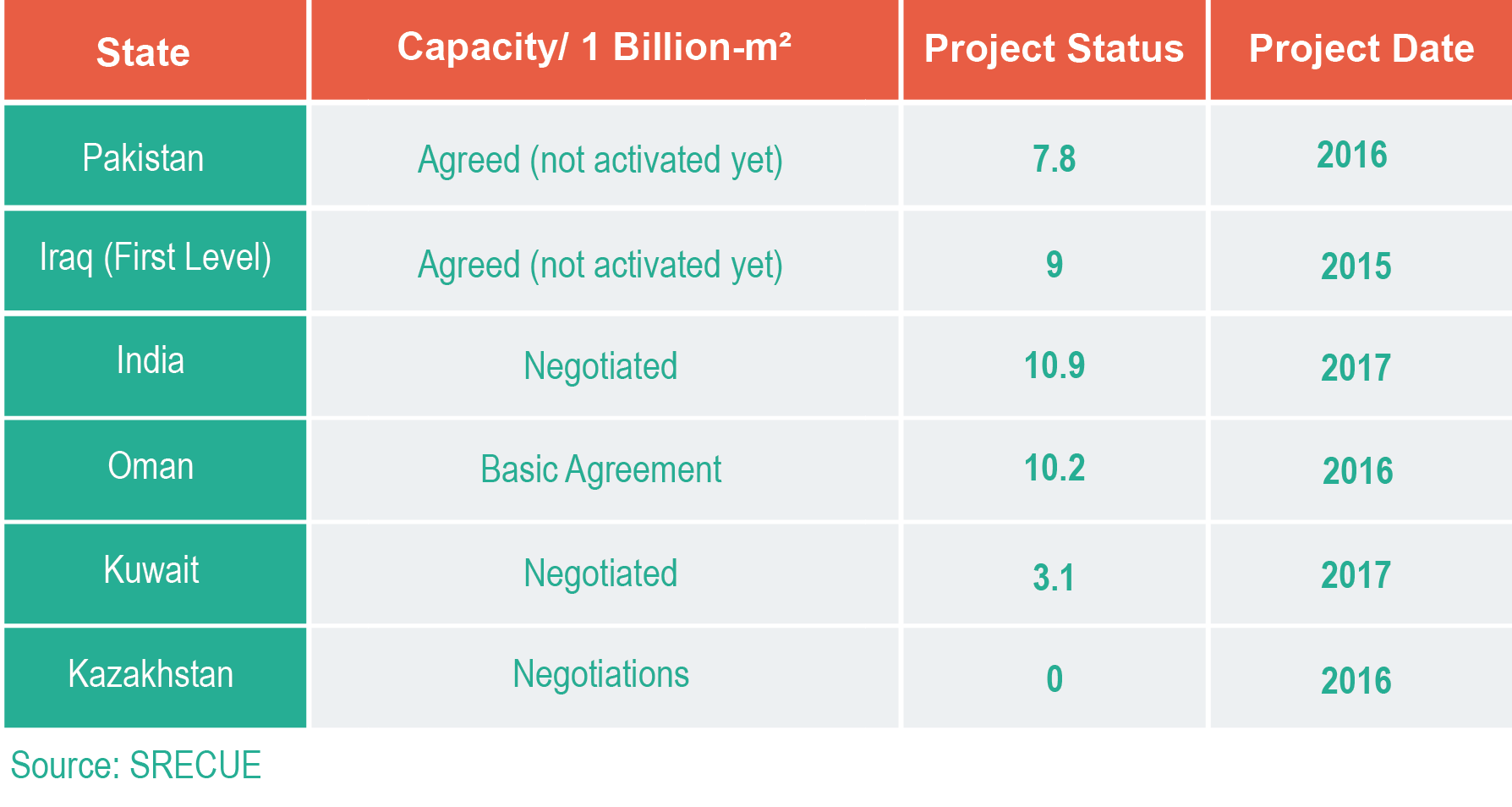

In their tireless pursuit of increased revenues from energy exports, Iran has entered into gas export agreements with several countries, although the majority of these are either still in the negotiations stage or have been signed but are yet to be implemented. The factors delaying implementation of these agreements include fast-moving international political changes and doubts over Iran’s ability to meet its promises, especially given its officials’ hostility to many international economic and political organizations.

These doubts don’t preclude recognition of Iran’s strenuous endeavors to complete the agreements that have already supplied it with the technology needed to implement them, in addition to its efforts to open new markets and to compete with leading neighboring countries in the export of energy, especially after the lifting of Western sanctions on technology transfer, at least in theory.

From this standpoint, Iraq is expected to become the largest importer of Iranian gas once the bilateral agreement signed between the two nations in August 2013 is implemented, with the six-year contract stipulating an initial supply of 7 million cubic meters of Iranian gas per day, gradually increasing until it reaches 25 million cubic meters two years after the start of the initial import process.

While the Iranian gas exports to Iraq were supposed to begin in May 2016, according to a statement by Assistant Iranian Oil Minister Hamid Reza Al-Iraqi in March of this year, they have not yet begun at the time of writing.

Tehran has also signed an agreement with Pakistan to export 7.8 billion square meters of natural gas per year, with the project, launched in 2016, still in the development stage. [6]

The regime is still in negotiations with India, Oman, Kuwait and Kazakhstan over exporting natural gas to these nations. India is set to become the largest importer of Iranian gas after Iraq, with an initial agreement to import 10.9 million square meters of Iranian natural gas daily beginning in 2017. Oman set to be the next largest importer, plans to import 10.2 million square meters of Iranian gas per day starting later this year, followed by Kuwait which will be supplied with 3.1 million cubic meters of Iranian gas per day from 2017. Meanwhile, negotiations are still underway to finalize the oil export agreement with Kazakhstan, which is set to take effect from later this year.

Most recently in May 2016, during a visit by the South Korean leader, Iranian officials signed an agreement on future shipments of Iranian liquefied gas to South Korea, with Tehran seeking access to South Korea’s advanced technology in developing the second phase of the South ‘PARS’ field [7]. As the fourth-largest importer of Iranian crude oil, South Korea is already one of Iran’s major trading partners in the energy field

» Third: the future of the Iranian oil and gas exports

Through the significant growth in Iranian oil exports to South Korea and India, we can conclude that Iran will continue its efforts to increase its oil exports in the near future. While South Korea and India are its largest growth markets, Iran is also exerting efforts to restore its oil exports to some African countries. Iran is also determined to use South Korea’s experience in technology to enable it to explore and develop its transport of gas from the oil fields, particularly liquefied gas, into a system with less wastage. Achieving this will take several years, however, and depends on many factors, including the continuing improvement of relations between the two countries without Western pressure on them, for example. According to experts, Iran’s experience in this area, particularly though not solely in the still-uncompleted South ‘Pars’ field, shows that such technological advances require years of work and development. [8]

The Iranian oil industry’s rising production rates and increasing export levels, along with its efforts to break into new markets, demonstrate the extent of the Iranian regime’s need for substantial financial resources, as well as emphasizing its determination to reach its goals of increasing production and export of oil and gas to pre-sanctions levels.

Achieving these goals in the current environment will not be easy, however, and may take years for a number of reasons, such as:

Importing Iranian oil and gas Present and Future

Recent declines in global oil prices, which have fallen by more than two-thirds over the past two-and-a-half years pose a major challenge for those companies just entering established markets and increasing their production. Iran will find it difficult to attract international companies to help it increase oil production since increased production and export levels mean raising supply levels over rates of demand and thus lowering prices, inflicting further damage on the interests of the international companies that have already suffered heavy financial losses during the past two-and-a-half years which have forced them to lay off a large percentage of their workforce and to accept lower profits. Give this situation , the companies are likely to help Iran with increasing oil production only in exchange for increasing their own percentage of the subsequent profits, thus reducing the Iranian regime’s revenue. At present, Iran has been forced to store surplus oil in massive offshore storage facilities due to a massive glut on the global market.

Rising domestic demand for natural gas in Iran is an obstacle to exporting large quantities in the near term. Another problem is the need for significant investment to build the infrastructure needed for pipelines and liquefied natural gas production; until those things are in place, Iran will not be able to take advantage or profit from its massive gas reserves since it also flares and burns the layers of natural gas in the oil extraction process. The lack of the technological infrastructure needed for natural gas processing and transport means that Iran is currently in third place globally behind Russia and Nigeria in terms of wasting gas and causing massive natural pollution by burning it off [9].

While Iran has signed agreements with neighboring countries to supply gas, it has not yet begun work on the infrastructure required to do so. Whilst Iraq, with which Iran signed a gas export agreement in 2013, should be the largest recipient of Iranian natural gas worldwide, work has yet to begin on the supply process, with the reason behind the delays still unclear.

Meanwhile, the GCC nations have made it clear that unlike Iran, they are able to withstand low oil prices for a long period, a policy adopted after the last OPEC meeting in Doha when Iran refused Saudi Arabia’s request to freeze oil production levels.

Moreover, given the heavy dependence of the Iranian economy on its oil industry, Iran will be unable to tolerate increased supply levels and continued low prices long-term, more especially while facing domestic economic crises, while Gulf countries can resist longer periods of lower production costs and have the financial reserves necessary to enable them to survive for longer periods with a commitment to policies that provide government expenditures at current levels. This is a contrast to the Iranian government’s budget, which is suffering a large deficit, especially with the additional burdens of foreign interventions in Syria and Yemen that may ultimately force it to accept a production freeze to maintain prices.

Another problem for Tehran is the continuing hesitancy of international oil companies, especially those from the US and Europe, to enter the Iranian market since, although sanctions have been eased, this does not mean they’ve been completely lifted.

Furthermore, Iran is also still in the probationary period in assessments of its willingness to meet its obligations on the development of its nuclear program and ballistic weapons. In the case of non-compliance with these obligations, the same sanctions will be fully reapplied within 65 days from the date of breach of terms of the agreement. These conditions exacerbate the existing uncertainty about the possible future of any oil contracts that may be signed by international companies with Iran [9], which are long-term contracts often requiring decades-long commitments. In addition to this Iran needs to invest over $500 billion over the next 12 years to maintain and develop its oil and gas production capacity.

The ‘Fitch’ rating agency recently stated that while Iran has the potential to become the largest exporter of liquefied natural gas by the end of the current decade at the earliest possible date, the country still needs to develop its liquefied natural gas production infrastructure, adding that those parts under construction and already completed show that this is likely to be excessively expensive and to take many years to finish. The ‘Carbon Tracker Initiative’ financial think tank has predicted that Iran is unlikely to produce large quantities of natural gas before the mid-2020s. [10], assessing that its future projects stand only a slim chance of success.

The CTI study also stated that Iran needs to invest at least $283 billion in its LNG production over the years. [ 11], although given the increasing global reliance on and investment in alternative energy the need for LNG is likely to decrease.

» Conclusion and Results:

The energy sector is the lifeline of the Iranian economy without which it cannot continue, as the regime relies primarily on energy exports to meet government expenditures and to meet its growing fiscal deficit, relying on exports to certain strategic partners in the field of energy. The largest importers of Iranian oil are respectively: China, India, Japan and South Korea.

Iran is seeking to take advantage of South Korean expertise in the field of liquefied natural gas technology and specifically the development of the South ‘PARS’ field, the largest gas fields in Iran. It also seeks to persuade international oil companies to work in the Iranian market and to help in increasing Iran’s oil production, as well as to open new markets in Eastern Europe and to attempt to restore its former African markets.

In the gas sector, Iran has been unable to date to exploit its massive gas reserves in order to significantly increase its exports, despite signing several agreements for the export of gas through pipelines to neighboring countries, some of which are not yet implemented, including with Iraq, which was supposed to be the largest importer of Iranian gas in the event of the implementation of its agreement. Moreover, the levels of its other gas exports remain modest, with relatively small amounts going to Turkey, Armenia, and Azerbaijan.

As the above report shows, Iran is striving to increase its oil exports to pre-sanctions levels in order to increase its limited financial resources, and to open new markets in various ways, including the sale of “affordable oil” at below world ; achieving this goal, however, is in reality contradictory to Iran’s objective and may ultimately force the regime not only to freeze production, but to reduce it in order to maintain reasonable price levels to escape its financial distress, with the global oil market currently suffering from a glut in supply and low prices. This is exacerbated by an increasing global trend towards investment in alternative and renewable energy sources, as well as by the needs of the Iranian oil and gas sector for investment and for huge financial resources and technology to keep pace with the times and increase the development of production, financial and technological resources which are unavailable to the government for the time being. Another problem for Iran is the international oil companies’ caution over entering into long-term contracts with the Iranian regime for fear of deteriorating future relations between Tehran and the United States and Europe.

All of these combined factors make it difficult for Tehran to reach its goal in the near term, and make it more likely that it will ultimately accept an agreement with OPEC to freeze production, especially if Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states continue to maintain low oil output levels for a long period, which cannot be borne by the Iranian budget in the long term.