The 2025 Iraqi parliamentary elections — the country’s sixth — hold extraordinary significance, extending beyond Iraq’s borders into a highly volatile regional context marked by intensifying geopolitical conflicts. Iraq is deeply entwined in these dynamics, particularly due to the competing interests of external actors within its territory. Unlike prior elections, which often culminated in routine consensus mechanisms for appointing the prime minister, these polls represent a pivotal moment that may shape Iraq’s stance on critical regional issues amid ongoing transformations.

Notably, these elections highlighted the influence of militias linked to external actors in Lebanon, Yemen and Palestine as well as Iranian apprehensions over a potential strategic shift that could redefine Iraq’s identity and orientation. Iraq is widely regarded as a cornerstone in sustaining the remaining elements of Iran’s regional geopolitical project, therefore the stakes of this electoral process were sharply heightened.

All internal and external actors perceived the 2025 elections as exceptional and decisive — a genuine test of control over Iraq amid critical regional developments. The elections presented a historic, perhaps unrepeatable, opportunity to forge a new political equation in Iraq and coincided with notable shifts in US policy under President Donald Trump, whose administration is intensifying efforts to diminish Iranian influence in Iraq and weaken the reach of its allied militias. This strategy follows US and Israeli objectives to neutralize Iran’s regional footprint, first in Lebanon and Syria, and now within Iraq. The United States is employing multiple mechanisms to counter Iranian interference in government formation and to foster an Iraqi political identity aligned with a regional axis independent of Tehran, or at a minimum, one reflecting a genuine balance of power.

The elections were thus widely viewed as a litmus test. Given their significance for internal power dynamics and broader Middle Eastern geopolitics — particularly with the anticipated parliamentary majority that will select the highest executive office — every shift is measured against its impact on the US-Iran regional confrontation. Key questions emerge in this context: What opportunities do the elections provide for redefining Iraq’s identity and orientation? How will electoral outcomes impact Iraq’s future political environment? What are the defining features of the new electoral map? What are the implications for Iraq’s various alliances and the distribution of power? How will Iran’s role in Iraq be affected? And finally, how will Iran adjust its strategic orientations in Iraq, particularly in light of unrelenting US pressure?

Iran’s Preponderant Role in the Sixth Iraqi Elections

In Iraq, each parliamentary term unfolds within a distinct electoral environment that shapes alliances and influences the overall outcome. The sixth electoral cycle stands out as markedly different from its predecessors. The first elections in 2005 occurred amid the aftermath of the US invasion and the initial phase of Iranian intervention, aimed at molding Iraq’s identity, deepening sectarian divisions and consolidating Shiite control in the country. The 2010 elections reflected an expanded the Iranian presence through military proxies, while the 2014 polls took place as Iran leveraged the US withdrawal and regional Arab Spring uprisings to further entrench its influence in Iraq.

The fourth parliamentary elections in 2018 occurred two years after Iran had consolidated its influence by integrating Shiism into Iraq’s political system through the approval of the Popular Mobilization Forces Law.[1] The fifth elections in 2021 followed a period of popular unrest, notably the October 2019 protests against Iranian interference.[2]

At the time, the regional landscape was also undergoing upheaval following the 2020 US assassination of Soleimani which aimed to deliver a major blow to Iran’s regional project, yet instability and Iranian influence persisted in Iraq. The current elections unfolded amid a regional context in which Iran and its militias have faced setbacks, and the United States has resumed a more active role in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon. These circumstances are expected to significantly influence the balance of power among Shiite alliances and the formation of the new Iraqi government.

External Developments

Compared with previous electoral cycles, external factors exerted the greatest influence on the sixth parliamentary elections. This placed Iran —the main architect of Iraq’s prevailing political identity — in a historically unprecedented position amid intensified US pressure to alter Iranian influence, and created an opportunity for political alliances to play a more decisive role in shaping the next phase of Iraq’s political landscape.

The Implications of Waning Iranian Influence

For the first time since 2005, Iraqi parliamentary elections took place amid a noticeable decline in Iranian influence. The Iranian establishment, which shaped the post-Saddam era, faces a historic predicament, having suffered significant blows to its centers of power* and the unravelling of the “Axis of Resistance,” the cornerstone of its regional project. This has created a new regional phase, forcing Iran into a defensive posture, limiting its ability to preserve Shiite dominance in Iraq, testing Shiite alliances like never before and opening opportunities for cross-sectarian coalitions. At the same time, Shiite communities in Iraq’s southern provinces aligned with Iran’s position over Gaza as documented on social media, particularly in the wake of Israeli and US strikes on Iran. This sentiment may have influenced voter attitudes toward Shiite alliances, particularly those with military backgrounds.

Consequences of the Post-October 7 Phase

Iraq is among the countries whose militias took part in the recent Gaza conflict, under the Iranian strategy of “unity of arenas,” proclaiming to defend Palestinians. However, militia activity witnessed a reduction following President Trump’s assumption of office in early 2025. Moreover, Israel’s unbridled aggression in Gaza may also have influenced the general mood of Iraqi voters and shaped their electoral behavior.

Increasing Turkish Influence in Iraq

The elections occurred amid Türkiye’s expanding role in Iraq, where Iran’s influence has long challenged Ankara both within the country and regionally. The early November 2025 signing of the water cooperation agreement marked a breakthrough in the longstanding water-sharing dispute, granting Türkiye authority to manage Iraq’s water resources and implement projects financed through Iraqi oil in exchange for water flow. This raised public concerns over growing economic and water dependence on Ankara, potentially undermining Iraq’s historic water rights and encroaching Turkish influence. Rising discontent on social media may threaten Turkish-backed Iraqi alliances like Siyada, while the Iraqi government seeks balance through a strong regional partner to limit Iranian pressure.

The US Pressures on Iraq

The decrease in Iranian influence over the elections is matched by mounting US pressure to dismantle the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) and reassert full state control over all unauthorized weapons. US pressure has taken shape through several clear steps and policy signals such as the following:

- -Appointing Mark Savaya as US envoy to Iraq: Analysts have portrayed him as a de facto US governor for Iraq. His opening remark — “I want to make Iraq great again” — was widely viewed as patronizing and provoked public anger. Trump appears inclined to manage Iraq directly from the White House, bypassing traditional diplomatic channels, while granting his envoy broad authority to operate across all levels. His earlier mediation with Iraqi militias to secure the release of his friend, Russian-Israeli researcher Elizabeth Tsurkov, showcased his Iraqi heritage, deep familiarity with the country’s dynamics and extensive network of contacts. His past involvement in the cannabis industry also fits Trump’s unconventional approach, which favors quick, pragmatic deal-making. For these reasons, Savaya is expected to play a central role in shaping Iraq’s political landscape. Trump has tasked him — one of the most prominent financiers of Trump’s campaign in Michigan, a decisive swing state — with three priorities: resolving the militia issue as a top objective; engineering the formation of the new Iraqi government, particularly its ministries such as finance, oil, interior, defense and the Central Bank governorship;[3] and restructuring US-Iraqi economic relations.

- -The US insistence on settling the militia issue: The Trump administration has made curbing the spread of uncontrolled weapons and redefining the parameters of Iraq’s relationship with Iran a core strategic priority. After years in which Washington relied mainly on sanctioning individual militia leaders, the US State Department escalated its measures in September 2015 by designating four factions as terrorist organizations.* The campaign also targeted the financial networks sustaining militia activity, including the Al-Muhandis Company, the economic arm of the PMF, along with several prominent bankers. Among them was businessman Ali Gholam, accused of smuggling oil and laundering funds through Iraqi banks on Iran’s behalf.

- -The Free Iraq from Iran Act: US lawmakers have introduced a bill* demanding an executive strategy to free Iraq from Iranian influence, in line with similar efforts in Syria and Lebanon. The proposed strategy calls for dismantling the PMF and other rogue armed groups, imposing sanctions on pro-Iran political, military and judicial actors and publicizing the abuses committed by militias against Iraqis who oppose Iran’s role. It also requires Iraq to halt its imports of Iranian gas.[4] The bill reflects the Trump administration’s reading of the entrenched militia-driven dynamics that shape Iraqi politics today.

Although such pressures have opened space for non-Shiite alliances to gain parliamentary seats, they have also generated sympathy for Shiite blocs opposed to US and Israeli objectives. Notably, one of the militias sanctioned by the United States ahead of the elections — Jund al-Imam —contested the vote as part of the Kadamat Alliance.

Changes in the Domestic Arena

Shifts in the external landscape have triggered corresponding changes within Iraq’s internal environment — developments that are poised to shape the future trajectory of electoral alliances, including the following:

The Coordination Framework Disintegrating Into Disputing Wings

The Coordination Framework* — long regarded as Iran’s most powerful lever in Iraq — is now embroiled in a fierce internal struggle. Its factions are divided over a second term for Prime Minister Mohammed Shia’ al-Sudani, control of the next phase of governance, the future of the PMF, the continuation of Fayyad’s leadership of the PMF and how to manage relations with the US administration. This turmoil follows the Coordination Framework’s fragmentation into rival blocs, a split driven by three core dynamics. First, Iran is confronting a moment of acute weakness, leaving it unable to manage or preserve cohesion within the Coordination Framework. Second, capitalizing on this vacuum, several Shiite leaders continue to compete for influence, positioning themselves for leadership. Third, intense US pressure has deepened rifts among the Coordination Framework’s components, opening space for alliances seeking a more balanced role.

As a result, the Coordination Framework has broken into distinct factions: the Sudani-Fayyad faction, the Maliki faction, the Khazali faction, the Amiri faction and the Askari faction. The sharpest confrontation is currently between the Sudani and Maliki camps, while the remaining factions shift between support and opposition depending on their interests, leverage and political orientations.

- -The Sudani-Fayyad Wing: This faction favors a flexible, balanced approach to regional dynamics and opposes former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki’s bloc. Key figures include Sudani, PMF Chairman Faleh al-Fayyad and Labor Minister Ahmed al-Asadi. They are supported by Ammar al-Hakim of the National Wisdom Party and Hadi al-Amiri of the Badr Organization. During the recently concluded elections, this faction supported a second term for Sudani and the retention of Fayyad as PMF head.

- -The Maliki Wing: Led by Maliki’s State of Law Coalition, this traditionalist faction backs a militia-centered state, opposes Fayyad’s continued PMF leadership and rejects Sudani’s second term due to his perceived prioritization of Iraqi interests over Iranian influence.

Despite the Coordination Framework’s current fragmentation, its factions may regroup following the conclusion of the elections. Historical patterns show that Shiite forces often deliberately fragment before elections to maximize seat gains, only to reunite afterward and form the largest parliamentary bloc.

The Boycott of the Elections by Formidable Forces

For the first time in the post-Saddam era, Iraq’s legislative elections occurred without the Sadrists. Their leader, Muqtada al-Sadr, announced a boycott, citing the participation of figures he deemed corrupt. The Victory Alliance, led by former Prime Minister Abadi, followed suit. Sadr had conditioned his participation on the principle of “not repeating past mistakes,” which included dismantling the current political class, disarming militias strengthening the army and police, safeguarding Iraq’s independence and non-alignment and committing to reform and accountability of corrupt officials.[5]

Analysts are split on the impact of Sadr’s boycott on voter turnout, with the emergence of two dominant views: First, the boycott represented a historic opportunity for Sadr’s opponents to secure more seats, echoing the post-fifth-term scenario. Second, rather than a permanent withdrawal, Sadr’s boycott represented a strategic pause in order to bide more time before reentering politics, waiting for the militia system to weaken — either through rising domestic discontent, external efforts to challenge the militia-based order, or renewed public mobilization under reformist banners.

In this context, Iraq’s top Shiite cleric Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani advised, “If a citizen believes participation serves Iraq’s best interest, they should vote for righteous and trustworthy candidates.”[6] This contrasted with clerics aligned with Maliki, who framed voting as a religious duty and abstention as sinful. Sistani’s guidance validated boycotts while aligning with Sadr’s emphasis on principled voting. Historically, boycotts have favored pro-Iran alliances, as in 2021 when Sadr’s withdrawal allowed them to form the largest bloc and pass ideologically driven legislation. Thus, Sadr’s electoral boycott could be viewed as a strategic misstep.

Violence and Assassinations Targeting Sunnis

As the elections neared, two Sunni candidates were targeted in October 2025. Baghdad Provincial Council member Safaa al-Mashhadani was assassinated, while Muthanna al-Azzawi survived an attempt in Yusufiyah three days later. Both districts, part of the Sunni Baghdad belt, host widespread militias. Shiite hardliners fear a new generation of Sunnis challenging corruption and arms proliferation. Mashhadani had spearheaded a council resolution to reclaim illegally seized lands,[7] a sensitive issue for militias, while Azzawi, a close ally, leads an e-governance initiative to modernize Baghdad’s provincial administrations, directly confronting militia control.

Map of Political and Electoral Alliances

Amid these shifts, 31 major alliances, 38 parties and 75 independent lists competed fiercely for 329 seats, a record in Iraq’s electoral history. The candidate pool rose to 7,743 — 5,496 men and 2,247 women — including current and former ministers, former parliamentary speakers like Mashhadani, around 250 fifth-term lawmakers and dozens of former members (see Table 1). Iraqi media reported that many alliances sought to replace familiar faces with new, popular candidates, a strategy that boosted their electoral appeal while reducing the prospects of established figures.

Table 1: Comparison Between the 2025 and 2021 Elections Data

| Election year | 2021 | 2025 |

| Number of voters | 22 million voters, casting ordinary and biometric tickets | 29 million, only 21 million of them obtained the biometric tickets* |

| Number of candidates | Total: 3225 Males: 2279 Females: 946 | Total: 7743 Males: 5496 Females: 2247 |

| Voter turnout | 43% | 56.1% |

| Determining criteria | The top vote-getter | Sainte-Laguë (proportional representation) system 1.7 |

| Alliances | 27 alliances comprising 108 parties | 31 major alliances comprising 38 parties |

Table created by Rasanah IIIS.

Iraq’s Shiite population is concentrated in the southern provinces — Najaf, Karbala, Dhi Qar, Basra, Babylon, Wasit, Qadisiyah, Maysan and Muthanna — while Sunni communities, including Kurds, dominate areas north and west of Baghdad, such as Anbar, Sulaymaniyah, Ninawa, Diyala, Erbil, Salah al-Din, Kirkuk and Dohuk. Baghdad itself is mixed. The following outlines the main alliances that competed to form the largest bloc in the 2025-2029 Parliament.

Shiite Alliances

For the first time since 2005, the sixth election cycle was distinguished by a multiplicity of competing Shiite candidates backed by both political and military factions. Earlier cycles were dominated by traditional leaders and military-backed alliances typically joined under political alliances, complicating the selection of the next prime minister. The following lists the most prominent Shiite alliances in this cycle.

Table 2: The Major Shiite Alliances

| Alliance | President, leader, secretary-general |

| Reconstruction and Development | Shia al-Sudani |

| State of Law | Nouri al-Maliki |

| National State Forces | Ammar al-Hakim |

| Sadiqoun | Qais al-Khazali |

| Badr Organization | Hadi al-Amiri |

| Huquq | Hossein Moanes |

| Khadamat | Nabeel al-Tarfi |

| Asas (Iraqi Foundation) | Mohsen al-Mandalawi |

| Abshir Ya Iraq | Hammam al-Hamoudi |

| Tasmim | Asaad al-Aydani |

| Badil | Adnan al-Zurfi |

| Other alliances | Ishraqat Kanoon; Faw-Zakho; Sumerians; Salah al-Din; Idrak; Thabitun; Support for the State; Diyala First; Our Partnership in Salah al-Din. |

Table created by Rasanah IIIS.

Political Alliances

- -The Reconstruction and Development Coalition: Formed by Sudani in May 2025, this new alliance brings together prominent political forces (see Table 3). Sudani established the coalition due to disagreements with the Coordination Framework leaders over his second term, Fayyad’s renewal, the future of the PMF and weapons proliferation. Analysts link his move to a desire for independence from Coordination Framework constraints, recognition of regional shifts offering a historic opportunity* and the need for a parliamentary bloc to advance — or block — key initiatives.

Table 3: The Elements of the Reconstruction and Development Coalition

| # | Forces | Leadership | # | Forces | Leadership |

| 1 | Tayyar al-Furātayn | Prime Minister Mohammed Shia’ al-Sudani | 6 | Ibda‘ Karbala Alliance | Karbala Governor Nassif al-Khattabi |

| 2 | al-‘Aqd al-Watani Alliance | Head of the Popular Mobilization Authority, Faleh al-Fayyadh | 7 | Hulul al-Watani Alliance | Mohammed al-Darraji |

| 3 | al-Wataniya Coalition | Former Prime Minister Iyad Allawi | 8 | Harakat Irada | Hanan al-Fatlawi |

| 4 | Bilād Sumer Gathering | Minister of Labor Ahmed al-Asadi | 9 | Ministerial figures | al-Asadi and al-Yasiri. |

| 5 | Ajyāl Gathering | MP Mohammed al-Sayhoud | |||

Table created by Rasanah IIIS.

- The State of Law Coalition: it is rivaled by the Reconstruction and Development Coalition and led by former Prime Minister Maliki, a traditional Iranian ally. This coalition comprises 14 political forces with tribal, popular and parliamentary bases (see Table 4). Its discourse leans heavily on sectarianism, aiming to maintain Iraq’s prevailing militia-based system. The alliance sought to block Sudani’s second term and bring Maliki to power for a third term, consolidating its influence within the existing political and military framework.

Table 4: The Elements of the State of Law Coalition

| # | Forces | Leadership | # | Forces | Leadership |

| 1 | Islamic Dawa Party | The Wing of Nouri al-Maliki | 8 | Shiite Human Movement | Yasser al-Maliki |

| 2 | Al-Hadbaa al-Watani | Hashem Fitiyan Rahim | 9 | Diyala First | Adnan Mohammed Abbas |

| 3 | Salah al-Din Alliance | Jamal Jaafar Kazem | 10 | Iraqi Wing Movement | — |

| 4 | Victory Bloc | Saleh al-Kazimi | 11 | National Oath Current | Abd al-Amir al-Assadi |

| 5 | Al-Nahj al-Watani Alliance | Abd al-Sada al-Furji | 12 | Islamic Iraq Coalition for Turkmen | Jassim Jafar al-Bayati |

| 6 | Hemam Movement | Wael al-Obaidi | 13 | Al-Luhaj Youth Movement | Abu Noor al-Nasiri |

| 7 | Men of Iraq | Zakaria al-Tamimi | 14 | Renaissance and Construction Gathering | — |

Table created by Rasanah IIIS.

- -The National State Forces Alliance

Observers describe this coalition as reformist in structure and moderate in orientation, led by Hakim, head of the National Wisdom Movement. Unlike other Shiite alliances, Hakim does not seek the premiership, reducing competition and conflict with fellow Shiite blocs. Generally close to and supportive of Sudani, the alliance includes seven political forces (see Table 5) comprising influential ministers and political leaders, holding significant weight within the Shiite political landscape.

Table 5: National State Forces Alliance

| # | Forces | Leadership | # | Forces | Leadership |

| 1 | National Wisdom Party | Ammar al-Hakim | 4 | National Orientation Party | General Secretariat |

| 2 | Arak Party | Mohammad al-Bawi | 5 | Arab Mashriq Party | Naeem al-Shuwaili |

| 3 | Jihad and Construction | Jawad Rahim al-Saadi | 6 | Tomouh Movement | Zaidoun Khezal |

Table created by Rasanah IIIS.

- -Asas (Iraqi Foundation): Formed in August 2023 and led by First Deputy Speaker Mohsen al-Mandalawi, a close ally of Maliki, the alliance aims to position him as a key Shiite political figure.[8] It brings together independent, moderate and youth-oriented parties, including Mustafa Jabbar Sand’s National Foundations Party and Ali al-Sharifi’s Standing Party, alongside civil, community and popular leaders.[9] Despite its ambitions, the coalition struggles with limited political experience, weak structures and flawed domestic and foreign strategies, making its electoral prospects dependent on convincing voters of its moderate, non-sectarian platform. In provincial elections, it won only two of 10 governorates.

- -Abshir Ya Iraq Alliance: Led by Humam al-Hamoudi, who frames it as a corrective project for Iraq,[10] the alliance includes influential Shiite forces notably Abdul-Hussein Abtan’s Iqtidaar Watan Party and Abdul-Karim al-Anzi’s Tanzeem al-Dakhil Party. It maintains a traditional Shiite discourse aligned with Wilayat al-Faqih, leveraging al-Hamoudi’s symbolic stature from his opposition to Saddam Hussein and advocacy against sectarian quotas.[11] Despite its historical and political weight, the alliance lacks a broad popular base, limiting electoral breakthroughs. It proposes Abdul-Hussein Abtan, former Minister of Sports and ex-Governor of Najaf, as a compromise candidate for government formation.

- -Tasmim Alliance: Founded in 2021 and led by Basra Governor Asaad Al-Eidani and lawmaker Amer Al-Amiri, head of the Alliance bloc in Parliament, it emerged amid declining influence of traditional Shiite parties like the State of Law Coalition, the Wisdom Movement and the Fatah Alliance. The alliance capitalized on the failures of successive Shiite governments to address national and local crises, particularly in Basra. Its locally focused discourse addressing Basra’s specific issues has boosted its popularity, making it more influential than traditional alliances in the province.

Military Alliances

- -The Sadiqoun List: This is the political wing of Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, led by Qais al-Khazali and considered the main competitor to the Huquq Movement. Its leading figure is Education Minister Naeem al-Aboudi who contested the elections independently, outside the Coordination Framework or broader Shiite alliances. Although sectarian at its core, it adopts a tactical public posture, seeking to reposition itself within major Shiite blocs by courting Sunni figures — such as Dr. Awan Kadhim al-Tikriti — and building ties with tribal leaders in Tikrit. It also maintains cordial relations with the Suwani region.

- -The Badr Organization List: This sectarian list serves as an alternative to the former Fatah Alliance. It is headed by Amiri, the Badr Organization’s secretary-general, a key Coordination Framework figure with close ties to Iran. Like Sadiqoun, it ran separately from the Coordination Framework and traditional Shiite alliances. The list represents the political arm of the Badr Organization, one of Iran’s oldest allied militias and retains a loyal support base in Basra and Wasit.

- -The Huquq Movement: The political arm of the Iraqi Hezbollah, designated as a terrorist organization by the United States. It is led by Kata’ib Hezbollah Commander Hussein Moanes (Abu Ali al-Askari), known for his proximity to Iran as well as his hardline rhetoric — such as his 2022 threat against former Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi. The movement began under the Coordination Framework but opted to run independently to expand its political footprint and secure seats that would reinforce the militia-dominated political order. It won one seat in 2022, but after the Sadrist withdrawal, its share rose to six seats.

Despite their electoral rivalries, all three militia-linked lists strongly backed the Gaza front and expressed full support for Palestinians, aligning with Iran’s support for Hamas. They also opposed Israeli and US strikes on Gaza, Iran, Lebanon and Yemen — positions that helped solidify Shiite popular support for their pro-Palestinian stance.

The Sunni Alliances

For the first time since 2005, Sunni alliances participated in the elections with minimal Iranian involvement, amid a regional and international inclination to sideline Iran’s influence in Iraq. The key Sunni alliances are listed in the Table 6 below.

Table 6: The Major Sunni Alliances

| Alliance | President, chairman, secretary-general |

| Taqadum Party | Mohammad al-Halbousi |

| Siyada Alliance | Khamis al-Khinjar |

| Azm Alliance | Muthanna al-Samarrai |

| Hasm (National Resolution Alliance) | Thabit al-Abbasi |

| Al-Jamahir al-Wataniya | Ahmed al-Jabbouri |

| Ninawa for Its People | Abdullah al-Yawar |

| Tafawoq | Ibrahim al-Namis |

| Arab Alliance | Rakan al-Jabbouri |

| Turkmen Front | Mohammed Samaan |

| National Identity | Rayan al-Kildani |

Table created by Rasanah IIIS.

Taqadum (Progress) Alliance

The largest, most influential and best-organized Sunni alliance was established in September 2019 under the leadership of former Parliament Speaker Mohammed al-Halbousi.* It brings together a group of the most prominent and impactful[12] Sunni alliances in both the Sunni arena and the broader Iraqi political landscape (see Table 7).

Table 7: The Elements of the Taqadum Alliance

| # | Forces | Leadership | # | Forces | Leadership |

| 1 | Taqadum Party | Moahmmed al-Halbousi | 4 | Qiyadah Alliance | Five Sunni leaders |

| 2 | Qimam Alliance | The minister of industry, leading figure within Taqadum Party Khalid Battal | 5 | Al-Anbar Hawiyatna (Anbar is Our Identity) | Ali Farhan al-Dulaymi |

| 3 | Parliamentarians | Raad al-Dahlaki, Haibat al-Halbousi, Fahd al-Rashid al-Dulaymi, Yahya al-Shaglawi, Ahmed Mazhar al-Jabbouri, Watban al-Jabbouri, Sara al-Dulaymi, etc. | |||

Table created by Rasanah IIIS.

Azm (Determination) Alliance

Classified as a tactically driven and functional alliance, it was established in April 2021 under the leadership of Muthanna al-Samarrai, head of the Civil Path Party. The alliance aimed to win enough parliamentary seats to position itself as a negotiating actor within the Iraqi political landscape. Some view it as a balancing force within the Sunni community — either representing Sunni factions seeking influence or functioning within a broader strategy by Shiite forces to weaken traditional Sunni power structures. Its relationship with Iran and the Coordination Framework is generally positive.* The alliance has a regional character, focusing on constituencies in Ninawa and Salah al-Din — particularly Samarra, Sharqat, Baiji and Tikrit. It encompasses a group of alliances and influential Sunni figures that provide it with a strong tribal and local base. These include the United Party led by Osama al-Nujaifi; the Iraq Victory and Peace Bloc; and prominent leaders such as Qasim al-Fahdawi, former Anbar governor and former Minister of Electricity; Talal al-Zubaidi, head of the Iraqi Glory Party; and Haider al-Mulla, a key figure within the alliance. Its platform calls for ending the international coalition’s military mission in Iraq and meeting Sunni demands.* However, its prospects of leading the Sunni political scene remain limited due to fierce internal competition among its senior figures for top posts — especially the speakership of Parliament — and a series of defections. In March 2024, five members broke away to form a new bloc, the Sadara Alliance, which included four sitting lawmakers.* Former parliamentarian Fares al-Fares also defected, reducing the alliance’s seats in the fifth parliament from 14 to 10.

Hasm (National Resolution Alliance)

Founded in July 2023 to participate in the provincial council elections, the coalition is led by then-Defense Minister Thabit al-Abbasi — who maintains strong relations with Türkiye, the UAE and Jordan — with former Speaker of Parliament Osama al-Nujaifi serving as secretary-general. It brings together a group of prominent Sunni tribal leaders and alliances.* The coalition calls for exclusive state control over weapons, combating corruption, ending Sunni marginalization, rebuilding areas liberated from ISIS and facilitating the return of internally displaced persons.[13] Its prospects, however, remain limited. The coalition functions more as a regional and pragmatic formation than a nationwide political project. It lacks a strong party structure, a broad support base and a clear ideological identity. Many of its leading figures belong to the older generation of Sunni hardliners who shaped the post-Saddam political landscape — an element that contributes to its generally positive relations with Shiite alliances. Observers believe the coalition may have been assembled to counter rising young Sunni leaders with broader popularity, such as Halbousi, Khanjar, Samarra’i and Janabi. As a result, it is often described as a functional coalition ready to strike deals even at the expense of Sunni interests. In addition, some of its members face corruption accusations, leading to comparisons with an association of corrupt officials.[14] The coalition has also drawn controversy because it is headed by a serving defense minister, despite constitutional provisions barring ministers of defense and interior, as well as military commanders, from engaging in political activity.

Siyada (Sovereignty) Alliance

An exceptional alliance that blends constituent and pragmatic characteristics, it was formed after the 2021 election results through the merger of the Taqadum and Azm alliances in January 2022, under the leadership of Khamis al-Khanjar. The merger aimed to strengthen Sunni influence within the largest parliamentary bloc tasked with forming the government. The alliance initially emerged as the largest Sunni force, holding 51 seats in Parliament (37 from Taqadum and 14 from Azm). However, it later suffered a series of defections — 15 in total, including 11 from Taqadum, 4 from Azm and the defection of Raad al-Dahkali from Siyada — reducing its seat count to 35 and weakening its electoral prospects. The alliance maintains moderate tribal and political influence in Anbar and Salah al-Din and enjoys regional ties with Türkiye and Qatar.

The Kurdish Alliances

The Kurdish alliances (see Table 8) in the Kurdistan Region — Erbil, Duhok and Sulaymaniyah — played a pivotal role in shaping the largest parliamentary bloc. The most prominent among these alliances are:

Table 8: The Kurdish Alliances

| Alliance | President, chairman, secretary-general |

| Kurdistan Democratic Party | Masoud Barzani |

| Patriotic Union of Kurdistan | Bafel Talabani |

| Al-Mawqif al-Watani (National Position Movement) | Ali Saleh |

| Kurdistan Islamic Union | Jassim al-Bayani |

| New Generation Movement | Sashwar Abdulwahid |

| Kurdistan Justice Group |

Table created by Rasanah IIIS.

Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP)

The largest and most organized Kurdish force, led by former Kurdistan Region President Masoud Barzani. It holds strong economic, security and political influence in Erbil and Duhok due to its control of the regional presidency and government, its extensive security and economic networks, tribal backing, historical legacy and support from several Turkmen groups.* The KDP maintains better relations with Sunni alliances than the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), and also enjoys ties with Türkiye and a number of Arab parties.

Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK)

Long regarded as the second major Kurdish force, led by Bafel Jalal Talabani. It holds significant security and popular influence in Sulaymaniyah, Halabja, and Kirkuk and has strong relations with key Shiite leaders and alliances close to Iran. Its prospects, however, are weakened by enduring organizational and structural challenges since the death of its founder, internal divisions — including a reformist wing led by Lahur Sheikh Jangi — and pressure from the New Generation Movement in Sulaymaniyah. As a result, it is expected to lose part of its base to the New Generation Movement, particularly among youth and independents.

New Generation Movement

A populist reformist bloc led by businessman and media activist Shaswar Abdulwahid, owner of NRT TV. It emerged as a response to what supporters describe as entrenched corruption and the dominance of the two main Kurdish parties. It enjoys strong popularity in Sulaymaniyah and lesser — but growing — appeal in Erbil and Duhok, attracting youth, intellectuals, independents and voters dissatisfied with the ruling parties. Although its presence is limited in tribal areas, rising public frustration has strengthened its electoral prospects.

Civil Alliances

The Badil Alliance

Founded on May 25, 2025, under the leadership of Adnan al-Zurfi, head of the Loyalty Movement, the alliance adopts a civil-technocratic discourse that opposes the militia state in all its forms and advocates for a full institutional state. It has accused the Sudani government of failing to control the proliferation of weapons and of engaging in cover-ups.[15] The alliance brings together national and civil groups seeking change, including the Independence Party led by Fifth-Parliament member Sajjad Salem, the Communist Party headed by Raed Fahmi and the Iraqi Intellectuals Party led by Dirgham Allawi. It banks on any potential political settlement to strengthen Zurfi’s chances of assuming the premiership, given his acceptance across Shiite, Sunni and Kurdish forces.

The Civil Democratic Alliance

Led by the widely accepted academic figure of the Tishreen movement Kazem Aziz al-Rifai, the alliance advocates for a civil state and includes several civic movements such as Renewed Horizon, the Social Democratic Current and the My Homeland National Initiative. Its support base consists of intellectuals, activists, and university professors. However, its chances in the recent elections were low due to its lack of a traditional party structure. Its influence remains confined to urban constituencies in Wasit, Najaf, Baghdad, and parts of the south, and it lacks both tribal backing and external support.

Military Affiliates

Over 1.3 million members of the Iraqi army, police, intelligence services and PMF, along with prison inmates, cast their ballots in the elections through “special voting” 48 hours before the general public vote.[16] This occurred despite repeated calls to maintain military neutrality and keep armed institutions out of electoral disputes, given the influence of political alliances over Iraqi military personnel — contrasting with the US military, where party influence is minimal. The military vote remains a significant factor in Iraq’s electoral balance, often proving decisive in closely contested districts, particularly in northern and western provinces that host numerous army, police and PMF units operating beyond oversight and under direct brigade commander orders. This dynamic can boost the vote share for alliances with a military background.

General Observations

Analyzing the map of electoral alliances reveals a strategic feature of division along sectarian and ethnic lines, echoing patterns seen in the 2018 and 2021 elections. This division also exists within the sectarian and ethnic components themselves. The Shiite alliances are now split into more than nine major coalitions, each encompassing dozens of smaller alliances, compared to five major alliances in 2021. Sunni alliances are organized into four major blocs, similar to 2021, while Kurdish parties form three alliances, and Turkmen parties participate through two alliances. The most prominent sub-features of this map include:

Multiple Leaders Within the Pro-Iran Bloc

Unlike the 2018 and early 2021 elections, when Shiite alliances divided into only two camps — a sectarian, pro-Iran militia-state camp led by Maliki and a cross-sectarian camp supporting institutions and balanced foreign relations led by Sadr — the 2025 elections witnessed an intense political struggle within the pro-Iran sectarian camp itself. This allowed new Shiite leaders to run independently with their own alliances, refusing to subordinate themselves to traditional figures. The absence of Iranian orchestration — no role akin to Soleimani to enforce cohesion — and internal boycotts by influential Shiite figures have contributed to this fragmentation. The prominent camps which vied for the premiership are listed below (see also Table 9).

- -The second term camp of Sudani, led by Sudani

- -The second term camp of Maliki, led by Maliki

- -The first term camp of the emerging forces, led by Zurfi and Sajad Salem.

Table 9: The New Leaders, Old Guard, Boycotters and Absentees

| The new figures who ran individually | Old figures running individually | Boycotters | Absentees | |

| Shia’ al-Sudani | Adnan al-Zurfi | Nouri al-Maliki | Muqtada al-Sadr | Mostafa al-Kazimi |

| Shibl al-Zaydi | Qais al-Khazali | Hadi al-Amiri | Haidar al-Abadi | Adel Abdel-Mahdi |

| Asaad al-Aydani | Mohsen al-Mandalawi | Faleh al-Fayyad | ||

| Naim al-Aboudi | Hossein Moanes | Hammam al-Hammoudi | ||

Table created by Rasanah IIIS.

Intra-Shiite Dispute to Consolidate Iraq’s Standing in the Post-2025 Election Phase

Given the opportunities created by Sadr’s absence and indications that some voters — motivated by support for Gaza and resentment over strikes on Iran perceived as punishment for its backing of Gaza and resistance against Israel and the United States — backed Shiite alliances. These alliances competed not only to win parliamentary seats, as in the fourth and fifth elections, but also to assert themselves as the leading Shiite forces controlling the political scene and to consolidate their role as key decision-makers in the post-2025 period.

Paramilitaries Running Individually

For the first time in two decades, the three armed militias — Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, the Badr Organization, Kata’ib Hezbollah and the Imam Ali Brigades — participated through independent alliances rather than under the umbrella of Shiite coalitions. This marks a significant split within both the militias and their allied blocs, reflecting a strategic move by militia leaders to assert themselves as independent actors and secure a prominent role in the next phase, particularly amid the waning influence of Iran’s patron states and the militias’ determination to protect their own interests.

Electoral Issues and Their Impact on Voters

The following outlines the most prominent electoral issues in the sixth parliamentary elections.

The PMF

For the first time in more than two decades, the future of the PMF is a central electoral issue. The dismantling of the PMF and controlling the proliferation of weapons has become a strategic goal of the United States and Israel, positioning the PMF’s future at the heart of Iraq’s political debate. Shiite alliances remain divided on the matter: pro-Iran factions — including the State of Law Coalition, the Badr Organization, the Sadiqoun List and the Huquq Movement — oppose dissolving the PMF, while cross-sectarian Shiite alliances, notably the Reconstruction and Development Alliance led by Sudani and the Najaf Marjaya advocate for dissolving the PMF and establishing a state monopoly on force.[17] Sudani has emphasized that “political activity and bearing arms cannot coexist,” asserting that there is a political consensus to eliminate all weapons outside state control.[18]

The Political System

Despite more than two decades since its adoption, the Iraqi system remains unable to effectively deliver services, maintain security, ensure stability or pursue an independent and balanced foreign policy. Iraq continues to operate under non-state dynamics, failing to transition fully to a functioning state framework. This is largely because the Shiite political system prioritizes sectarian agendas over national programs, advancing sub-Shiite interests rather than the broader Iraqi community and aligning with Iranian objectives. Consequently, many Iraqis seek a political transformation that removes sectarian and consensus-based power-sharing, which has hollowed out the system’s democratic content. Achieving this would require constitutional amendments under Article 142 of the 2005 Constitution. As a result, a broad segment of voters is inclined to support cross-sectarian alliances such as the Sudani-led Reconstruction and Development Alliance.

Rampant Corruption

Iraq ranks among the most corrupt countries in the 2025 Corruption Perceptions Index, placed 140th out of 180 nations. Within the Arab world, it ranks eighth among the most corrupt states.[19] Former Anti-Corruption Committee member Saeed Yassin estimated in September 2021 that roughly $360 billion[20] had been smuggled abroad, while Iraqi legal researcher Ali al-Tamimi raised the figure to around $500 billion[21] in August 2025. Such massive plundering helps explain the dysfunction across Iraq’s sectors, despite the country’s vast oil wealth. The positions and anti-corruption efforts of political coalition leaders significantly influence voters’ decisions.

Iraqi Identity

Iraq is witnessing a debate over the country’s identity, shaped by the positions of internal and external actors. Some Shiite alliances, backed by Iran, emphasize a sectarian identity, while other alliances, supported by external actors, aim to promote a unified national identity. Against this backdrop, Iraqi voters largely recognize the country’s Arab heritage and its rich historical civilization, prompting many to support alliances that transcend sectarian divides, strengthen the nation-state and advocate a balanced approach to foreign relations. Historically, the modern Iraqi state was established by Iraqi Sunni Arabs following the decline of Turkish and Persian influence. Iraq is a historically ancient entity, endowed by Arabism with more than 1,400 years of distinction, authenticity and enduring regional role.[22]

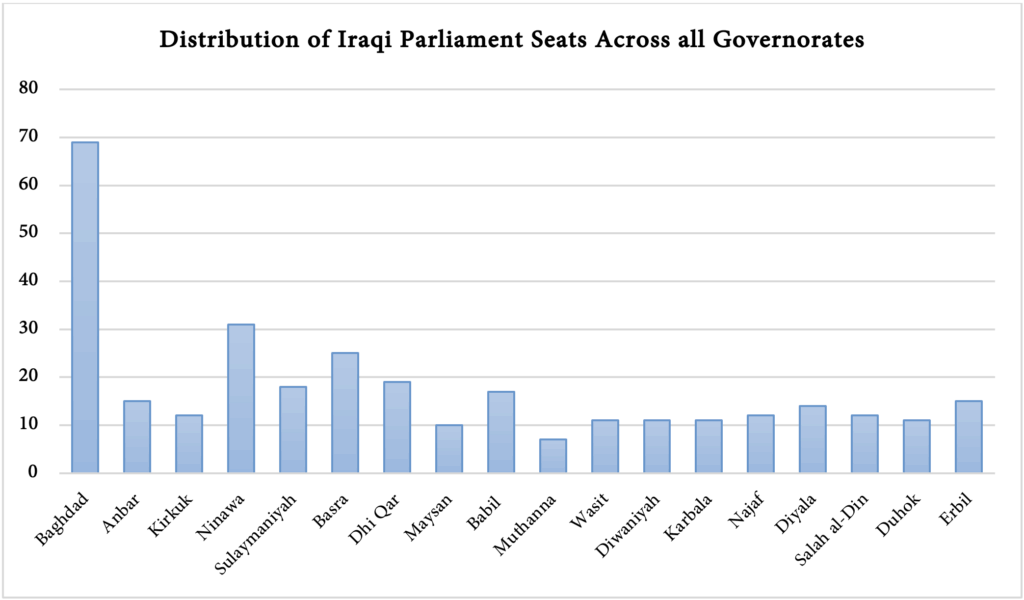

Election Results and Alliances’ Quotas

The Iraqi Council of Representatives comprises 329 seats, as stipulated by Law No. 4 of 2023, with allocations across Iraq’s 18 governorates based on population (see Figure 1). Of these, 320 are regular seats, including a 25% quota (83 seats) reserved for women, while 9 seats are designated for minority groups: five for Christians, one for the Feyli Kurds in Wasit,* one for the Shabak in Ninawa, one for the Yazidis in Ninawa and one for the Mandaean Sabeans in Baghdad.[23]

Figure 1: Distribution of Iraqi Parliament Seats Across all Governorates

Figure created by Rasanah IIIS.

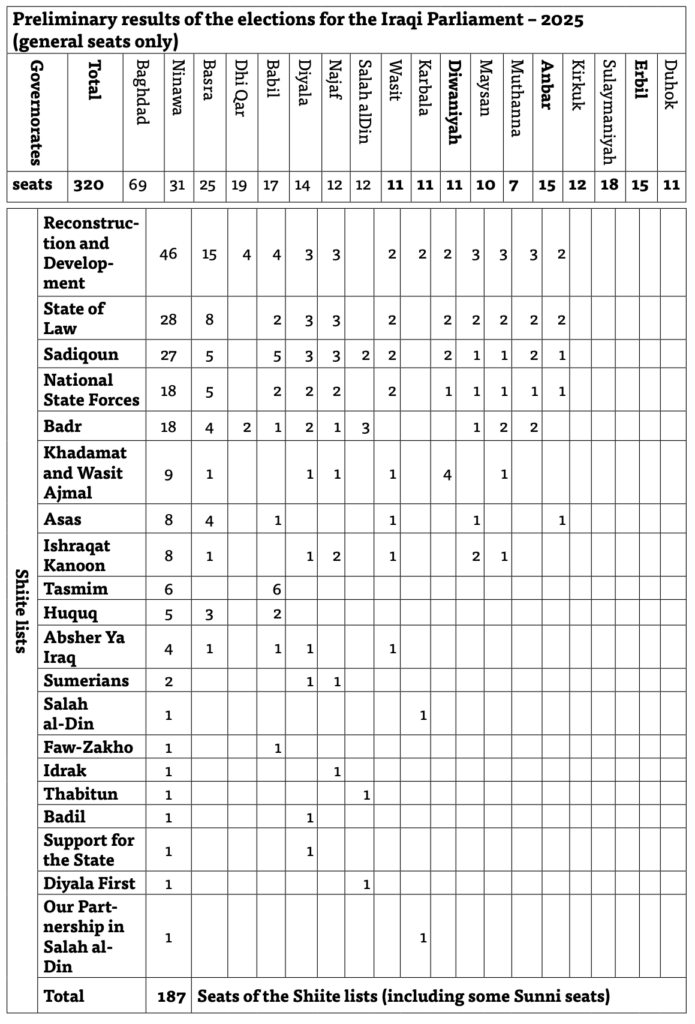

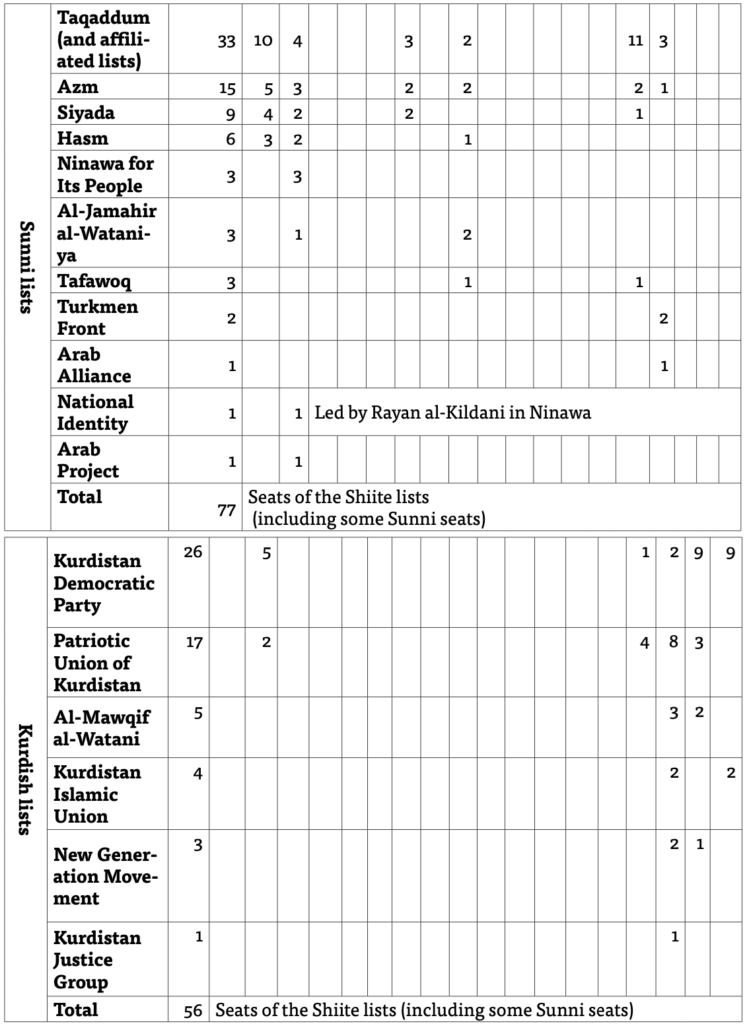

According to the preliminary results of the electoral commission, the distribution of quota rankings for the electoral alliances in the 2025-2029 Parliament was as follows (see the tables below):

Table 10: Positions and Seats of the Alliances by Governorate — Shiite Lists

Table 11: Positions and Seats of the Alliances by Governorate — Sunni and Kurdish Lists

Source:https://urli.info/1eAl9

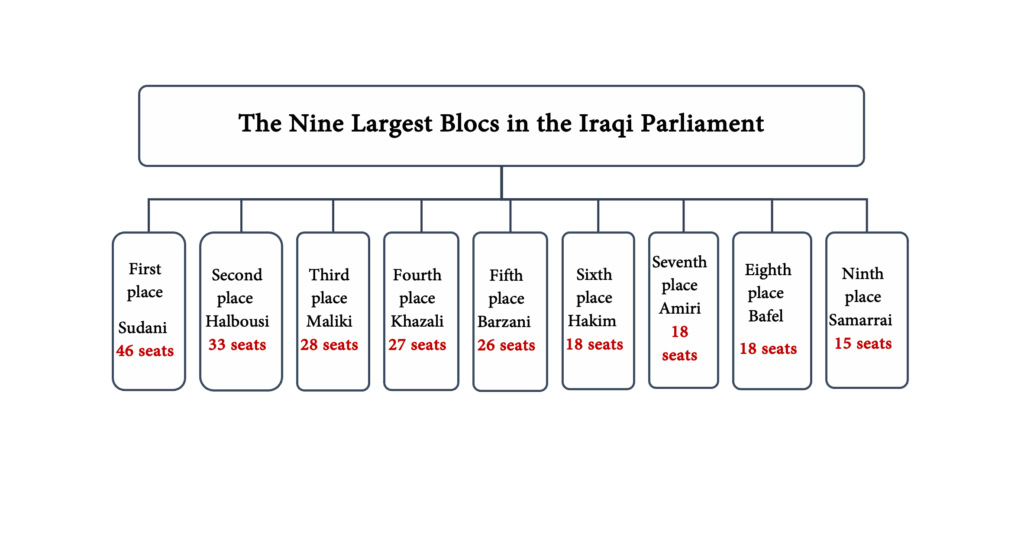

Figure 2: The Nine Largest Blocs in the Iraqi Parliament

Table created by Rasanah IIIS.

First Place: Reconstruction and Development (Sudani)

He emerged as the leading force, securing 46 seats out of 329, an impressive increase of 44 seats compared to the two he won in the 2021 elections (see Table 12). He ranked first in Baghdad, Qadisiyah, Najaf, Karbala, Muthanna, Maysan, Dhi Qar and Babylon and placed second or third in Basra, Salah al-Din, Ninawa and Wasit. This performance grants him substantial influence in the new Parliament and a strong negotiating position.

Table 12: Electoral Outcomes

| Alliance | Leader | 2021 seats | 2025 seats |

| Reconstruction and Development | Sudani | 2 Furatayn | 46 |

| Taqadum | Halbousi | 37 | 33 |

| State of Law | Maliki | 33 | 28 |

| Sadiqoun | Khazali | 15 | 27 |

| Kurdistan Democratic Party | Barzani | 32 | 26 |

| National State Forces | Hakim | 2 | 18 |

| Badr Organization | Amiri | — | 18 |

| Patriotic Union of Kurdistan | Bafel | 15 | 15 |

| Azm | Samarrai | 14 | 15 |

| Khadamat | Shibl | — | 9 |

| Huquq | Askari | — | 6 |

Table created by Rasanah IIIS.

Service-Oriented Achievements

Sudani leveraged his expertise to address citizens’ concerns and alleviate service-related crises, earning widespread popular support. This restored public confidence in the political process and strengthened his position as a formidable competitor, surpassing traditional hardline figures like Maliki.

Political Pragmatism

With such a rational, realistic approach, Sudani navigated regional transformations to benefit Iraq’s national, regional and international interests. He managed to rise above sectarian pressures, prioritizing Iraqi interests and guiding the country through a turbulent period.

Balance and Acceptance

Sudani enjoys broad domestic support — from influential military leaders like Fayyad and Amiri, to liberal figures such as Allawi, and popular ministers including Ahmed al-Asadi and Hayam al-Yasiri. Externally, he has backing from select Arab countries and carefully maintained relations with the United States. Reports suggested that his victory was secured through assuring the United States that his government would reduce Iranian influence in Iraq and grant Washington influence over five key government positions: defense, interior, finance, oil and the central bank.[24]

Positions on Key Issues

Sudani aims to establish a state monopoly on weapons, reform the political system to prioritize collective national interests, reinforce Iraq’s Arab identity and combat corruption.

However, going forward, pro-Iran alliances could pose challenges by blocking legislation, exploiting uncontrolled weapons or leveraging Maliki’s influence. This is particularly significant since Sudani did not achieve the number of seats won by the Sadrists who led the 2021 elections with 73 seats.

Second place: Halbousi’s Taqadum Alliance

Halbousi retained his second-place position from the 2021 elections, winning 33 seats — a drop of four from the previous cycle. He received strong support in Anbar and Baghdad, moderate backing in Ninawa and Diyala and weaker support in Kirkuk and Babylon. His continued second-place ranking is explained by several factors:

Leadership Factor

Halbousi is seen as a consensus-building Sunni leader who embraces a moderate, institutional and balanced approach. This makes him an acceptable political figure across diverse communities, earning him Sunni support in both Sunni-majority and mixed provinces.

Political Ideology

He promotes national moderation, rejects sectarianism, injustice, marginalization and violence, and opposes ethnic, regional, or sectarian conflicts. He advocates for a civil state, territorial integrity and peaceful coexistence among all groups, favoring non-violent methods for political change.*

Supporting Forces

His coalition includes influential executive, parliamentary and independent figures with political, tribal, and economic weight, backed by technocratic and administrative elites across the provinces where they operate.

Third Place: Maliki’s State of Law

He retained his third-place ranking from the 2021 elections but lost five seats, winning 28 in 2025. His party drew support in the southern and central provinces, including Baghdad, Karbala, Dhi Qar, Muthanna, Qadisiyah, Najaf, Maysan and Babylon. Despite the decline in seats, he maintains influence in the south due to the following factors:

Personal Symbolism

Maliki belongs to the hardline generation within the Shiite community, especially in the southern provinces. He played a key role in shaping post-Saddam Iraq and served two consecutive terms as prime minister.

Network of Influence

He retains extensive connections across the parliamentary, executive and judicial branches, possesses significant financial resources, and controls uncontrolled weapons that can be leveraged to destabilize or exert influence.

Strategy of Fragmentation

Maliki has used side alliances to fragment his opponents, limiting their prospects while strengthening his own electoral position.

Mobilization and Polarization

Four sitting ministers ran on his list — Oil Minister Hayyan Abdul Ghani, Electricity Minister Ziad Ali Fadhil, Youth and Sports Minister Ahmed Al-Mubarga and Agriculture Minister Abbas Al-Ulayawi — alongside numerous current and former lawmakers.

Limitations

His influence is constrained by his image as a symbol of a militia-based state facing strong US pressure, the weakening of his Iranian support and the broader “Axis of Resistance,”, and widespread negative public perception. Consequently, he did not secure first place in any provinces but came in second, third, or fourth.

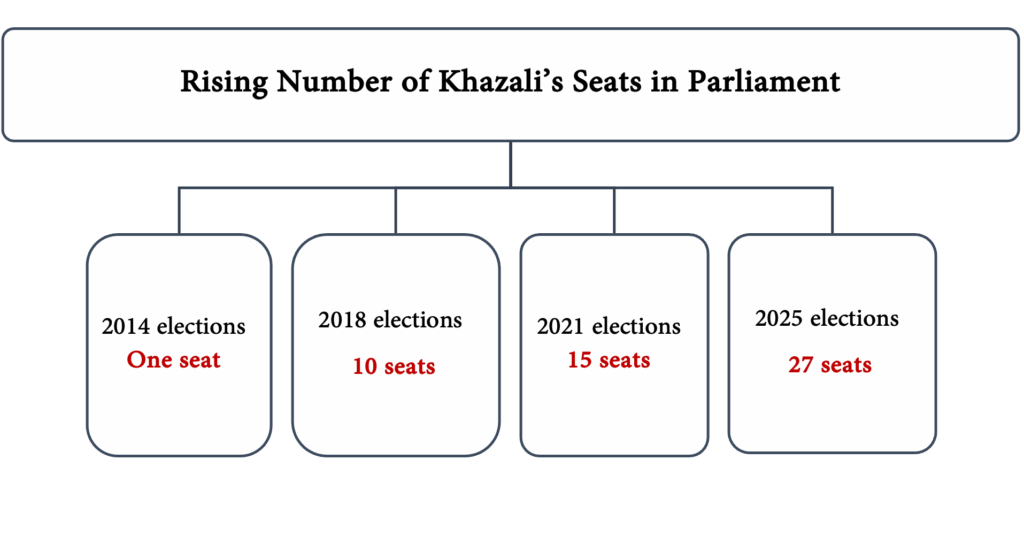

Fourth Place: Khazali’s Sadiqoun

The Sadiqoun bloc’s leap to fourth place was unexpected, as it won 27 seats in 2025. This marks an increase of 12 seats from the 2021 elections, when it secured 15 seats, 17 seats more than in 2018, and 26 seats higher than in 2014 (see Figure 3). The results indicate a steady upward trajectory in Sadiqoun’s parliamentary gains across election cycles. Analysts and the Iraqi public have offered multiple explanations for this growth.

Figure 3: Rising Number of Khazali’s Seats in Parliament

Table created by Rasanah IIIS.

Military Influence

Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq holds key positions within the PMF and competes with Kata’ib Hezbollah, giving it considerable influence over voters. It also commands several independent brigades outside the PMF, which significantly impacted voter turnout.

Alignment With Sudani

During Sudani’s tenure, Khazali aligned with the government’s domestic and foreign policies, including avoiding attacks on US targets. This reflects his political pragmatism and belief in leveraging the political process for power, unlike other militia leaders who prioritize militarism.

Independence From Iran

Unlike other pro-Iran militias, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq maintains a degree of autonomy in decision-making and enjoys strong ties with the government through its political, social and economic branches, some funded by the Iraqi state.

Origins and Ambitions

Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq emerged locally as a splinter from the Mahdi Army (Saraya al-Salam), loyal to Sadr. Unlike militias that primarily execute Iranian agendas, it actively seeks political power.

Support for Gaza

Its visible support for the Gaza front boosted its public standing, as citizens welcomed any opposition to Israeli actions. When it urged the government to intervene for Iraq’s interests, it complied — unlike other militias — enhancing Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq’s reputation for pragmatism.

Fifth Place – Kurdistan Democratic Party (Barzani)

The party declined to fifth place in 2025, securing 26 seats, mirroring its position (25 seats) in 2018 and down from 32 seats in 2021. This decline reflects growing public dissatisfaction in Erbil and Duhok over Masrour Barzani’s government’s poor economic and service performance. Its 2021 seat increase had been driven by support for the tradition to statehood and responsiveness to the October 2019 protests.

Sixth Place – National State Forces Alliance (Hakim)

The alliance surged from two seats in 2021 to 18 seats in 2025, recovering 16 of the 18 seats lost, compared to 20 seats in 2018. This leap elevated it to fourth place, overtaking the Kurdistan Democratic Party’s previous rank. Its resurgence is attributed to:

Candidate Selection

Hakim fielded candidates with strong popular support in Najaf, Baghdad Muthanna, Dhi Qar and Basra, promoting an unconventional reformist discourse both domestically and internationally.

Alignment With Sudani

The alliance endorses Sudani’s reconstruction and development approach, emphasizing a balanced political program that prioritizes Iraqi state interests.

Personal Symbolism

Hakim draws legitimacy and influence from his family legacy, the Hakim family, which holds deep historical and popular significance in Iraq.

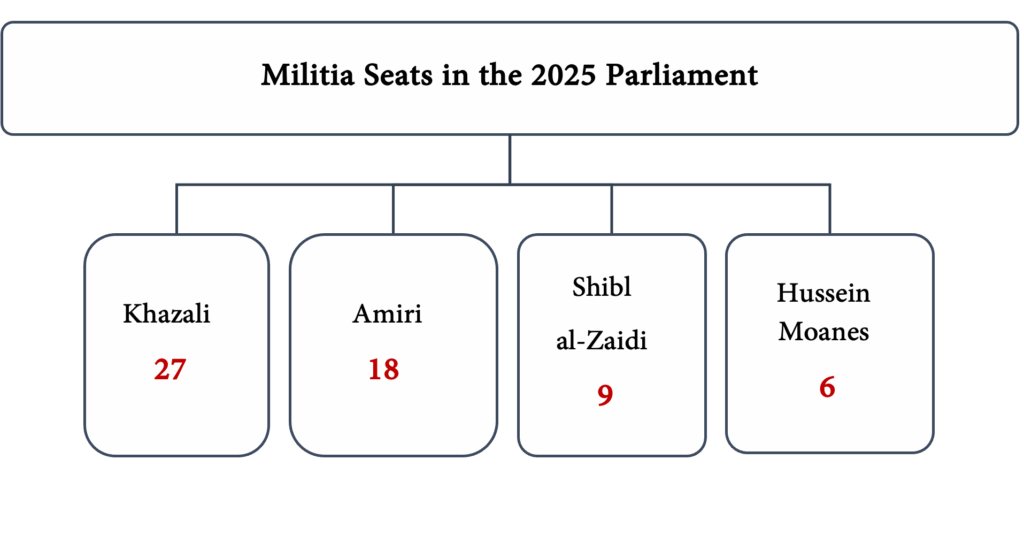

Seventh Place: Badr Organization (Amiri)

Amiri’s Badr Organization advanced by winning 18 seats, joining other militias that gained representation in the 2025 elections, including Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (27 seats), Khadamat-Kata’ib al-Imam Ali (nine seats) and Huquq-Kata’ib Hezbollah (six seats). Collectively, militias hold about 60 seats, 14 more than the first place group (see Figure 4).

If Maliki’s bloc adds its 28 seats, it would reach 88 seats. Further inclusion of other Coordination Framework alliances, such as the Civil State Forces (18 seats) and additional alliances like Ishraqat Kanoon (8 seats) and Abshir Ya Iraq (4 seats), could bring the total to 118 seats — exceeding the “blocking third” of 110 seats. This gives Maliki the practical ability to obstruct government formation unless countered by pressure from the Trump administration.

Figure 4: Militia Seats in the 2025 Parliament

However, this arrangement is difficult to realize due to internal disagreements within the Coordination Framework and the ongoing power struggle between the Maliki and Sudani factions. As a result, Khazali is unlikely to align with Maliki, leaning instead toward Sudani. In this case, Maliki’s bloc would lose its 91 seats and its blocking minority, allowing Sudani to advance more easily.

The militias gained unexpected electoral seats thanks to votes from members of the PMF and the army, their opposition to foreign presence in Iraq, their stance against Israeli aggression on Arab and Palestinian lands and their selection of influential candidates such as Transportation Minister Razzaq Muhaibis, former Interior Minister Mohammed al-Ghabban, MP Hamid al-Moussawi and the head of the PMF committee in Karbala, Abu Murtada al-Karbalai. The Sadiqoun bloc also nominated Education Minister Naeem al-Aboudi and attracted Sunni figures like Dr. Awan Kadhim al-Tikriti, forging tribal alliances in Tikrit. Nevertheless, American pressure against the prevailing militia logic in Iraq may weaken their chances of securing executive positions in the next government.

Lagging Positions

Most of these were from Sunni and Kurdish components, as well as civil Octoberist and liberal currents. The Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) placed eighth with 18 seats, up from 15 in 2021. The Azm Alliance fell to ninth with 15 seats, compared to 14 in 2021. Siyada secured nine seats, the Decisive Alliance six seats, the National Position Alliance five seats and the New Generation Movement three seats.

Losing Positions

The Badil (Alternative) Alliance, led by Adnan al-Zurfi, won only one seat according to some sources — or four according to others — despite Zurfi’s notable influence due to his nationalist stance. The alliance shows weak presence in tribal and rural areas and limited reach in urban centers compared to more established alliances.

Notable leaders and lawmakers who lost in the electionsinclude:

-Mahmoud al-Mashhadani, outgoing speaker of Parliament from the Azm Alliance

–Prominent lawmakers in the Taqadum Alliance: Dhafer al-Ani, Yahya al-Muhammadi al-Shajlawi and Fahd Rashid al-Dulaimi

–Independent Sunni lawmaker Sheikh Shaalan al-Karim State of Law lawmaker Aqeel al-Fatlawi

-Rising civil lawmaker Sajjad Salem, formerly part of the Zurfi bloc.

Significations of the 2025 Election Results

The election results and the shares of the Shiite, Sunni and Kurdish alliances that contested the 2025 parliamentary elections reveal the following conclusions:

Restoring Confidence in the Political Process

Voter turnout reached 56.11%[25] in 2025, a significant rise from 43% in 2021, adding nearly 3 million new voters. This increase was surprising, given the environment suggested a decline: strong support for election boycotts — especially by the Sadrists — and the electoral commission’s restriction of voting to biometric cards, which barred over 7 million electronic card holders from voting.[26] Turnout had been declining for a decade due to public distrust in the political process, fueled by corruption, poor living conditions and inadequate public services in a country rich in strategic resources.

The reversal of this downward trend in 2025 can be attributed to several factors:

The Silent Majority

Iraqi media[27] estimates that about 4 million additional voters participated in 2025. This indicates that the Sudani government’s performance motivated the silent majority to vote, restoring trust in the political process and granting the government renewed popular legitimacy, compared to apathy in previous elections.

New Faces

Many alliances replaced familiar candidates with new, more popular figures, which helped mobilize voters.

Political Money

Alliances shifted mobilization priorities from sectarian affiliation to political spending, including using social media influencers. Candidates were categorized as diamond, gold, or silver based on vote-buying budgets, with prices reaching up to 700,000 dinars[28] per vote depending on the candidate.

Complicated Cabinet-formation Process Eases Compromise

The issue of no single alliance achieving the 165 seats required to form the largest bloc (out of 329) is not new. What is new is the fragile balance of power within the Shiite political establishment, with factions holding nearly equal numbers of seats — meaning there is neither a clear winner nor a loser. This complicates government formation and emphasizes the need for consensus.

Sudani faces a complex political struggle to renew his mandate. The Coordination Framework maneuvered to form the largest bloc while excluding Sudani, and disagreements persist over the structure of the new government.

This mirrors what happened in 2021, when Sadr won 73 seats — more than Sudani’s 46 — but could not form a government because the Coordination Framework exercised the blocking third. A similar tactic could be applied against Sudani.

The distribution of power among winning factions means that no party can form a government without consensus, a norm since 2003. This is further complicated by the strengthened presence of militias in the new Parliament, likely prolonging government formation, possibly repeating delays seen in previous elections. However, if the US administration applies pressure on the militia-influenced state and its institutions, a government could be formed more swiftly.

Emboldening the Militia State Over the Civilian State

The fact that the four militias participating in the elections secured 55 seats, while most civilian alliances failed to win any (except for Badil, which gained only four seats), highlights a strengthened militia presence in the new parliament and the broader Iraqi political scene. This could result in:

- -Passing more sectarian laws to reinforce Iraq’s Shiite identity

- -Amending the Popular Mobilization Forces Law to consolidate military influence

- -Enacting economic, security, and political legislation aligned with Iranian interests

- -Complicating US efforts to restrict weapons exclusively to the state for any new government.

Meanwhile, civil, Tishreeni, and liberal alliances — such as the Badil-Zurfi Alliance and the Civil Democratic Alliance — were sidelined, winning no seats despite their on-the-ground presence. This outcome shocked opposition groups against the dominance of political Islam and could hinder many civil and non-civil projects opposed to the militia state.

The reasons include: defections of civil figures to traditional and governmental alliances, divisions within the civil movement over election participation, and the overpowering influence of campaign financing, political media, and the militias’ unchecked weapons, which made competition nearly impossible.

Zurfi described his loss as part of an unequal battle: a civil project dependent solely on citizens’ belief in a civil state and change, confronted by the exploitation of power and political money.

The External Factor and the Engineering of the New Cabinet

The 2021 election scenario — where Maliki and Sadr faced off — is being mirrored in 2025 between Maliki and Sudani, as neither faction secured a clear majority to form the largest bloc. This bloc will likely emerge only after returning to consensus, influenced by regional developments that were largely unfavorable to Maliki and intense US pressure aimed at shaping Iraq’s next phase.

For the first time, external actors — particularly the United States — may play a more decisive role than internal forces in government formation. This reflects regional and international efforts to recalibrate Iraq’s internal power balance following October 7, amid historic setbacks for Iran that weakened its position and may encourage it to temporarily retreat.

The United States is expected to manage the next phase politically rather than militarily, seeking stability in a country without a viable alternative leadership. Consequently, the Trump administration appears to place its hopes on the new government to guide Iraq’s trajectory in the coming period. Most arenas in the region have shifted, creating a new regional equation, with Iraq as a critical pivot.

The upcoming phase will likely feature a contest between internal and external actors, each aiming to shape Iraq’s future according to its interests. The country cannot remain in its current state of limbo. Among the most prominent candidates for forming the new government are:

Former Prime Ministers and Established Figures

This group includes Kadhimi, Abadi, Fayyad, -Zurfi and Asaad al-Eidani.

New Candidates

Emerging figures include Intelligence Chief Hamid al-Shatri, Interior Minister Abdul Amir al-Shammari, Higher Education Minister Naeem al-Aboudi, State of Law lawmaker Othman al-Shaibani, as well as Dr. Ali Shukri, Abdul Hussein Abtan, Qasim al-Araji, Ahmed al-Asadi, Naeem al-Suhail, and Basim al-Badri.

Competing Candidates

Maliki is considered the least likely to secure the premiership, though his influence remains significant. Sudani is the frontrunner, yet his position is not guaranteed; he could still be sidelined. His coalition faces vulnerabilities, as key seats are controlled by figures such as Fayyad, Asadi and Haider al-Gharifi, leaving them open to Maliki’s influence, potentially threatening Sudani’s coalition in a manner similar to what happened with Abadi when Fayyad withdrew support.

Consensus Candidate

This could be one of the aforementioned figures or a previously unconsidered candidate who emerges through negotiation and compromise.

Table 13: Government Formation Procedure

| First step | The president of the republic calls on the new Parliament to convene within 15 days from the date of the announcement of the official election results |

| Second step | The Parliament speaker and his two deputies are elected by an absolute majority (half plus one) during the first session), which is chaired by the oldest member, and this post is customarily reserved for a Sunni |

| Third step | Parliament elects the president of the republic within 30 days from the date of the first session, and he must obtain a two‑thirds majority; this post is customarily reserved for a Kurd |

| Fourth step | The president of the republic tasks the nominee of the largest bloc with forming the new government, and this post is customarily reserved for a Shiite Arab |

Conclusion and the Iranian Engineering of the New Cabinet

Iraq remains central to Iran’s strategy for clear political, economic, geographical and security reasons. Unlike other arenas, Iraq’s proximity allows Tehran to maintain influence at a lower cost, especially after losing control in Syria and witnessing the weakening of its proxies in Lebanon Yemen, and Palestine. Iran is aware that the emergence of a non-aligned Iraqi government could accelerate the state’s centralization, reducing the militias’ sway and obstructing Iranian interests — particularly if the government insists on consolidating weapons under state control. Iranian officials, including Foreign Ministry Spokesman Ismail Baghaei and Ambassador Mohammad Kazem al-Sadegh publicly acknowledged US involvement in the elections while claiming Tehran would respect any electoral outcome.[29]

Nevertheless, Iran’s influence over the sixth elections was minimal due to its weakened regional position. Yet, the results indirectly favored Iranian objectives: the tight competition among alliances increases the potential success of pro-Iran coalitions, the militias control roughly 55 parliamentary seats that could shape government formation if aligned with Maliki and Coordination Framework allies and secular, civil-state alliances suffered a decisive defeat.

At the same time, Iran faces significant constraints: the establishment’s own vulnerabilities, fragmentation within the “Resistance Axis,” concern over potential new Israeli-US strikes, the steadfast support of the United States for Israel and the Trump administration’s determination to reduce Iranian influence in Iraq. Just days before the elections, the United States appointed a special envoy to directly influence Iraq’s next phase. Should US engagement weaken, Iran could revert to a 2021-style scenario, backing Maliki to exploit the “blocking third” tactic if it cannot control the largest bloc. This would complicate government formation, as holding over a third of parliamentary seats enables proxies to obstruct key decisions requiring a two-thirds majority such as electing a president — effectively delating the appointment of the prime minister, as occurred when the Coordination Framework forces blocked Sadr in 2021.

Ultimately, Iraq’s upcoming phase will serve as a critical test of US influence in shaping the country’s political landscape.

[1] “The Parliament Voted on the PMF Law and Began Reading the Trade Agency Organization Law,” Iraqi Parliament, November 26, 2016, accessed November 5, 2025, https://bit.ly/3n74K7q. [Arabic].

[2] Protests in Iraq: Demonstrators from all social classes, sects, affiliations and regions of Iraq raised slogans and chants hostile to Iran and its proxies in Iraq, such as “Iran out, Basra free, free” and “Iran out, Iraq remains free.” Protesters set fire to the Iranian consulate in Najaf three times during the demonstrations, targeted the Iranian consulate in Karbala, burned the Iranian flag in multiple Shiite provinces, stomped on images of the supreme leader and Qasem Soleimani and attacked militia headquarters. They also renamed Khomeini Street to “Martyrs of the 1920 Revolution Street.” See also: “Iraq Protests: Baghdad Free, Free – Iran Get Out,” YouTube, October 4, 2019, https://bit.ly/4rb5pFf. [Arabic].

* Targeting Iran’s strategic assets: Iran systematically eliminated many leading nuclear experts and a significant number of top military commanders close to Khamenei, responsible for implementing the establishment’s internal and external policies. Additionally, a large portion of Iran’s ballistic missile and attack drone stockpiles as well as nuclear facilities at Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan, were destroyed.

[3] “Washington Informs Baghdad: The Ministries in the Next Government and Who Will Occupy Them Will Be Exclusively Our Choice,” Al-Rasheed TV (Iraq), accessed November 12, 2025, https://urli.info/1ev-7. [Arabic].

* Militia groups: Harakat al-Nujaba, Kata’ib Sayyid al-Shuhada, Harakat Ansar Allah al-Wafiya and Kata’ib al-Imam Ali.

* Bill prepared by Republicans and Democrats known for their hardline stance on Iran, led by US Congressman from South Carolina Joe Wilson, published on his website on April 5, 2025: The bill is part of a package of anti-Iran legislation introduced by the Republican Study Committee — the largest Republican caucus in Congress — including the “No Hezbollah in Our Hemisphere” Act, the “Maximum Pressure on Iran” Act, the “Sanctions Waiver Repeal” Act, the “Prevent Iranian Energy” Act and the “Countering Iranian Terrorism” Act, aimed at imposing additional sanctions on the Houthis and Tehran-aligned factions.

[4] “H.R.2658 – Free Iraq From Iran Act,” U.S. Congress, accessed November 12, 2025, https://2h.ae/DTmv.

* Shiite political and military blocs in Iraq: the State of Law Coalition led by Nouri al-Maliki, the Fatah Alliance led by Hadi al-Amiri, the Huquq Movement led by the Spokesperson of Kata’ib Hezbollah Iraq Hussein Moanes (Abu Ali al-Askari), the National Wisdom Party led by cleric Ammar al-Hakim, the Victory and Reform Alliance led by former Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, Kata’ib Hezbollah Iraq led by Abu Hussein al-Mohammedi, Harakat al-Nujaba led by Akram al-Kaabi and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq led by Qais al-Khazali. Most of these alliances and militias endorse the concept of a sectarian state, based on sectarianism, political accommodation, dependency and alignment with Iran.

[5] “Al-Sadr Renews His Election Boycott and Calls for the Surrender of ‘Loose Weapons’ and the Disbanding of Militias,” Rudaw, July 4, 2025, accessed November 5, 2025, https://bit.ly/3X3eaDB. [Arabic].

[6] “The Marjaya Protects Those Who Boycott Saying Participation in Elections Is a Matter of Personal Conviction,” Al-Wathika, October 20, 2025, accessed November 7, 2025, https://bit.ly/4p0mnom. [Arabic].

[7] “Baghdad Provincial Council Issues Important Decisions Regarding Agricultural Lands and Investment,” Al Arabiya ABC, October 14, 2025, accessed November 7, 2025, https://urli.info/1j44J. [Arabic].

* The biometric ticket is the automated card with a fingerprint, unlike the ordinary paper card, designed to prevent forgery.

* The disintegration of the “Axis of Resistance,” the Iranian establishment’s predicament and intense US pressure to disband the Popular Mobilization Forces and confiscate the weapons of rogue armed militias.

[8] “Supreme Council President: ‘Abser Ya Iraq Is a Reform Initiative,’” Alsumaria, January 20, 2025, accessed November 5, 2025, https://bit.ly/4p0kg3Y. [Arabic].

[9] “Announcement of the Launch of Iraq’s Largest Civil Political Coalition Under the Name ‘Iraqi Foundation Coalition,’” Al-Alam Al-Iraqiya, August 22, 2025, accessed November 8, 2025, https://urli.info/1jk4a. [Arabic].

[10] Ibid.

[11] Michael Knights, Hamdi Malik and Amir al-Kaabi, “Profile: The Hoquq Movement,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, March 15, 2024, accessed November 5, 2025, https://bit.ly/4ibwKmK.

* His prominent participation was in the 2018 Parliament, when he was elected speaker with the support of the Al-Bina’ Alliance, which maneuvered to keep Iraq within Iran’s sphere of influence and protect Iranian interests in Iraq under Nouri al-Maliki and Hadi al-Amiri. He was then elected speaker again in 2021, also with the backing of the Coordination Framework. In both instances, he was compelled to join Shiite blocs due to the withdrawal and volatility of Muqtada al-Sadr, from the coalition that usually includes the Sadrist Movement, Sunni alliances (Azm and Taqadum) and Kurdish alliances (Kurdistan Democratic Party), known as the Reform and Construction Alliance after the 2018 elections or Save the Nation Alliance after the 2021 elections. He advocates returning Iraq to the Arab sphere to preserve its Arab identity and rejects sectarianism, leaving Halbousi no choice but to rejoin the Shiite-led coalition under Maliki and Amiri.

[12] “Electoral Conference of Baghdad Taqadum Party Organizations Supporting President Al-Halbousi,” YouTube, November 8, 2025, accessed November 9, 2025, https://urli.info/1jbtP. [Arabic].

* The alliance condemned the two bombings that occurred in Iran in 2024, in Kerman near Qasem Soleimani’s cemetery and also condemned Israel’s assassination of Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah, eulogizing him as a brave, devoted and great leader. See also: “After Today’s Bombing, ‘Azm’ Confirms Its Solidarity With the Iranian People,” Alsumaria, January 3, 2024, accessed November 9, 2025, https://2u.pw/Dfql1. [Arabic].

* Returning displaced people from Sunni provinces to their homes, resolving the issue of the missing since the fight against ISIS, punishing those who committed crimes against Sunnis and rebuilding Sunni provinces using state funds rather than waiting for donor money, as well as controlling rogue weapons. See also: “TV Interview With Azm Alliance Leader Haider al-Mulla on Al-Rabiaa Iraqi Channel,” YouTube, March 13, 2025, https://2u.pw/fxrUQ. [Arabic].

* Prominent figures include Mahmoud al-Mashhadani, Talal al-Zubai’i, Khalid al-Obaidi and Muhammad Nouri al-Jubouri.

* Such as Sunni leader and former MP Qutaiba al-Jubouri, former Foreign and Finance Minister Rafi’ al-Issawi, founder and head of the Al-Hal Party Jamal al-Karbouli and former Commerce Minister Salman al-Jumaili.

[13] “Announcement of the Formation of the Hasm Alliance,” Anadolu Agency, July 19, 2023, accessed November 9, 2025, https://2u.pw/Ud3oN3Z. [Arabic].

[14] “‘Hasm:’ A New Iraqi Alliance With Old Faces,” Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, July 31, 2023, accessed November 8, 2025, https://2u.pw/r821Pz. [Arabic].

* Turkmen Development Party, Turkmen Democratic Party, Turkmen Democratic Movement, Turkmen National Salvation Party, Turkmen Intellectuals Association, Turkmen Liberal Association and Turkmen Youth Party in Kirkuk.

[15] “Al-Zurfi: Iraq Lost $20 Billion Due to the Stoppage of the Region’s Oil, and the Government Covers Militia Activities,” Kurdistan 24, November 6, 2025, accessed November 10, 2025, https://urli.info/1eoSK. [Arabic].

[16] “Iraqi Parliament Election Law No. 9 of 2020,” Official Gazette of Iraq, November 5, 2020, accessed November 8, 2025, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://moj.gov.iq/upload/pdf/4603.pdf. [Arabic].

[17] “Sistani Calls for Integrating Participants in the Fight Against ISIS Into the Security System,” Sky News Arabia, December 15, 2017, https://bit.ly/4p1pRGY. [Arabic]. See also: “Al-Abadi Expresses Surprise at the Fears of the ‘Post-ISIS’ Period and Presents a 7‑point Vision for the Future,” Asharq Al-Awsat, January 16, 2017, https://bit.ly/4a4Bt7v. [Arabic].

[18] “Prime Minister: There Is Consensus Among All Political Forces to End the Presence of Any Weapons Outside State Institutions,” Iraqi News Agency, November 5, 2025, accessed November 9, 2025, https://urli.info/1ekC6. [Arabic].

[19] “Iraq Ranks 140th Globally in Combating Corruption,” Baghdad Today, February 3, 2025, accessed November 9, 2025, https://urli.info/1j8dT. [Arabic].

* Since the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime, Iran quickly implemented a plan to change Iraq’s identity, launching a propaganda campaign against Arabism and linking it to Iraq’s deteriorating situation. All Arab symbols and facts were suppressed to pave the way for a “new Iraq” stripped of its Arab identity in favor of a Persian identity, effectively isolating Iraq from its Sunni Arab environment. See Also: Dr. Laqaa Makki, “Arabism in Iraq: A Living Reality That Cannot Be Ignored,” Al Jazeera, October 5, 2005, accessed November 9, 2025, https://bit.ly/48mor42. [Arabic].

[20] “$360 Billion in Funds Were Smuggled out of Iraq, and Two Entities Are Working to Recover Them,” Iraqi News Agency, September 9, 2021, accessed November 8, 2025, https://urli.info/1ekVw. [Arabic].

[21] “Estimated at $500 Billion: Legal Researcher: Recovering Iraq’s Smuggled Funds Is Possible Through International Agreements,” Iraqi National News Agency, August 8, 2025, accessed November 9, 2025, https://bit.ly/3LPYuB9.

[22] Ghassan Al-Imam, “Is Iraq’s Arab Identity in Danger?” Asharq Al-Awsat, July 13, 2025, accessed November 9, 2025, https://urli.info/1joeH. [Arabic].

* The Feyli Kurds are Shiite and speak a Kurdish dialect that differs from those found in Iraqi Kurdistan.

[23] “Seat Distribution for the 2021 Iraqi Parliament Elections,” Independent High Electoral Commission, accessed November 30, 2021, https://bit.ly/3K4aBKq. [Arabic].

[24] Al-Rasheed TV (Iraq), “Washington Informs Baghdad: The Ministries in the Next Government and Who Will Occupy Them Will Be Exclusively Our Choice.”