With the failure of the United States and Russia to extend the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) for a year as a band-aid, ambiguity of intentions and secrecy of actions will lead the world to continual uncertainty and insecurity. The New START — agreed upon between US President Barack Obama and his Russian counterpart Dmitry Medvedev in 2010 — encountered its momentous slippery slope in 2023 when President Vladimir Putin suspended it unless the White House ceased its military support for Ukraine. Moscow also demanded the inclusion of London and Paris in future arms control talks. Whereas on-site inspections remained suspended since the COVID-19 pandemic, the Kremlin started withholding biannual data on nuclear facilities and forces, notifications on treaty-accountable items like ballistic missiles and launchers and sharing of telemetric information on the testing of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), prompting a tit-for-tat response from the Pentagon. Though the United States opted against increasing its deployed nuclear arsenal in 2024, the incumbent president not only opposed further extension of the New START but also allocated funds available after February to exceed its technological and operational perimeters. While the United States’ nuclear arsenal modernization plan is facing delays, Russia is developing various new types of nuclear weapons. Trump aspires to build the Golden Dome defense shield, besides adding more nuclear warheads to its submarines. Putin’s offer to extend the accord for a year failed to impress Trump, as Russia is perceived to be buying time to resolve technological deficiencies in its nuclear arms development. Thus, the last effective bilateral strategic arms control accord is no more after 15 years.

The United States and Russia agreed to deploy no more than 1,550 strategic nuclear warheads each. Each side was restricted to 700 delivery systems, including:

- Land-based ICBMs

- SLBMs

- Heavy bombers

- A combined limit of 800 deployed and non-deployed launchers was set for these delivery vehicles.

Notifications were mandatory for activities involving strategic weapons, such as missile tests and bomber movements. Data exchanges were conducted to share information about the number of deployed missiles and delivery systems. On-site inspections were permitted to ensure compliance. The treaty did not limit non-strategic nuclear weapons, despite Russia’s substantial inventory of over 1,000. It did not restrict new strategic weapons systems. The inclusion of a limit on non-deployed launchers was intended to prevent rapid expansion of deployed numbers beyond treaty limits, a scenario known as “breaking out.”

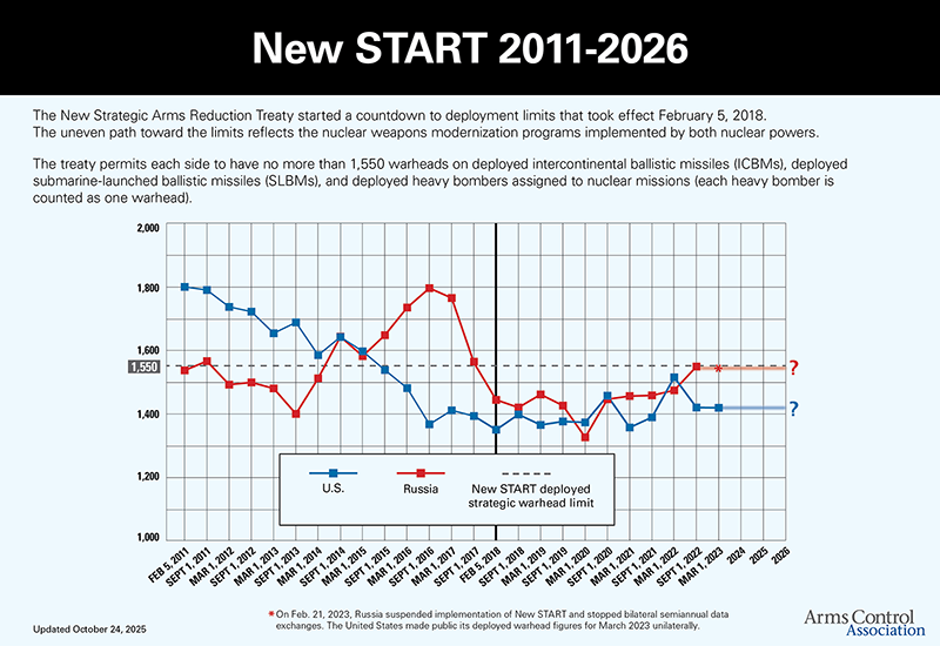

Figure 1: New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (2011-2026)

“If it expires, it expires,” Trump told The New York Times. “We’ll do a better agreement” after the expiration. The United States wants to include China, whose expanding nuclear arsenal numbers between 600 to 800. He also wants other nuclear powers in on any future accord, too. None has shown interest. His perspective changed altogether in the second term of his presidency. Trump used to pitch himself as Reagan’s arms control negotiator in the late 1980s. He then advocated denuclearization. His Russian counterpart had no qualms about comprehensive arms control. Putin seeks to undo the Soviet Union in any way possible. The world is faced with a nuclear arms race.

Suppose the United States wanted to expand its deployed strategic forces; it could quickly bring reserve warheads online. One straightforward step would be to increase the missile load on its ballistic‑missile submarines from the current four‑or‑five missiles per boat to a maximum of eight, adding roughly 800 to 900 warheads to the submarine fleet, giving the force far greater firepower and likely making it trigger-happy once firing is authorized. The US Air Force is also ready to restore B‑2 and 76 B‑52’s capability to carry Minuteman III ICBMs. The aircraft were taken off alert and their weapons placed in storage in 1992. There are no treaty constraints on the number of nuclear-capable B-21 Raiders in service.

While the United States focuses on modernization of its nuclear arsenal, Russia is likely to make more of the same until the technological challenges to its new heavy ICBM the RS-28 Sarmat and the likes are duly addressed. By all means, Moscow does retain a substantial capacity to add warheads to its strategic forces, especially its SS-18 Satan ICBMs. For long-term needs, its scientists, engineers and spies are working to ready five types of next-generation weapons, which Putin has prematurely declared developed and deployed.

Owing to Ukraine’s Operation Spider Web, one-third of Russia’s nuclear bombers — Tu-95MS and Tu-22M3 — were destroyed or significantly damaged. With its invasion proving too slow and costly, Russia’s defense industry remains haemorrhaged with sanctions barring imports of western machinery, alloys and advanced equipment, including microprocessors. Hence, the expensive feat of producing its legacy or new nuclear bombers would neither be smooth nor quick. Moscow may contend to produce more legacy ICBMs, albeit with piecemeal upgrades, in the short term. Experts believe that Russia can add 400 additional warheads across the Russian ICBM force.

Russian and US nuclear planners are locked in assuming worst-case scenarios, leading to increased investments in nuclear forces, conventional forces, cyber and AI capabilities and missile defense systems. China suspended strategic stability talks with the United States in 2024, citing disrespect for China’s core interests. Mutual distrust as well as the fantasy of a comprehensive nuclear arms control treaty involving all nuclear-armed states is a recipe for disaster in a hyper-polarized world. None of the nine nuclear-armed states — the P-5, Israel, India, Pakistan and North Korea — would ignore the worst-case scenario and save on its arsenal growth. If Russia is developing more advanced nuclear weapons and the United States is unwilling to support its allies, then what would stop Canada, Germany, Poland and South Korea, or even Japan from pursuing their own nuclear deterrence after quitting the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)? Has the time for Kenneth Waltz’s more-may-be-better discourse really come? Washington and Moscow should freeze the status quo by extending the treaty for a year or more, thereby reverting to respecting data-sharing verification mechanisms.