The Communist experience failed with the collapse of the Soviet Union, giving rise to 15 independent republics after they had gone through economic, social, and military turmoil. Boris Yeltsin, the first Russian president following the collapse of the Soviet Union, believed that dismantling the costly Soviet empire and pursuing a market economy were critical to achieving prosperity and to ensure that the Russian people were lifted out of abject poverty. Perhaps he was not aware that his successor, Vladimir Putin, had a totally different vision. Since ascending to power in 2000, Putin has worked systematically to develop a plan to revive the Soviet empire as he considered its dissolution 30 years ago to be a great humiliation. It is clear that the end goal of President Putin is to reverse the outcomes of the Cold War which enabled NATO to gain a foothold in the traditional Russian areas of influence. NATO established military bases and deployed missiles — posing a direct threat to Russian national security.

Despite his efforts, Putin will not succeed in reviving the former Soviet empire. Nonetheless, it seems that he is rushing headlong to reimpose Russian dominance over some former Soviet republics, primarily Ukraine. This country is considered to be a strategic route into Russia, and NATO’s expansion into it would compromise and expose the Russian Lebensraum (living space). Using diplomatic methods with several European presidents along with the US President Joe Biden, Putin tried to ensure that Ukraine adopts a neutral position in regard to the West. But his efforts were in in vain. Putin lost patience, and he started his military campaign against Ukraine on February 24, 2022. Through this military campaign, Putin aims to re-establish a geopolitical buffer zone that Russia’s rulers throughout the country’s history — from the Tzars to the Bolsheviks — felt necessary for their own survival. The ongoing developments in Ukraine indicate that the Russian ambition is to ensure that Ukraine totally spins in Moscow’s orbit — away from NATO — or at least to keep it neutral or to ensure control over it through creating two pro-Russian independent republics: Donetsk and Luhansk. Both were officially recognized by Russia on February 21, 2022.

The Strategy of the Russian Lebensraum

Lebensraum is an old concept with an inherently colonial nature. The Lebensraum of countries varies depending on their understanding of the concept of Lebensraum, and the interests they seek to secure. According to the concept of Lebensraum, a living space grows like a living creature and stretches like rubber to encompass land, sea, air, and space. Weak states most often do not seek to expand at the expense of their neighbors since they lack the necessary means. Major states— against the backdrop of competition for global supremacy and the pursuance of qualitative superiority over their foes — find themselves prompted, though illegally, to expand their borders at the expense of their neighbors. They also may exercise their economic influence at the expense of weaker states — even if this leads to the deployment of military force.

The Concept of the Russian Lebensraum

The concept of Lebensraum was the reason behind the colonial expansion of several countries in the era that followed the Industrial Revolution. The need arose for raw materials and markets to export finished products. Thus, this concept emerged to make a case for stronger countries to occupy weaker ones and expand at their expense. In the 19th century, Western countries took control of regions and states in Africa, Asia and Latin America. It is important to note that prior to this Western colonialization, the West deemed these regions backward and not worthy of exploiting for their resources, potential and location.[1]

The geopolitical concept of Lebensraum gained momentum in the 1930s. The Nazis extensively used it to restore Germany’s power and clout which it lost following its defeat in World War I. The Nazis expanded into neighboring countries to secure the raw materials to build “the German nation.”

During the Cold War between the Eastern and Western camps, the concept of Lebensraum was manifested in the behavior of the two disputants and their proxy warfare in most of the Third World countries. Since the end of the Cold War —except for the US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the Iranian Shiite geopolitical expansion at the expense of the Arab countries — the concept of Lebensraum has significantly diminished which is primarily based on dominance and monopoly of clout. This concept has gradually been replaced by different forms of international cooperation and economic competition. The aforementioned have characterized the new system of international relations amid the upsurge in globalization.

However, it seems that Russia under Putin has clung on to the old concept of Lebensraum, which turns bordering countries — especially those that were part of the former Soviet Union — into normal areas of influence for Moscow, as well as some distant countries that could serve as military bases such as Syria. Putin’s application of the concept of Lebensraum is no different than what Friedrich Ratzel, the godfather of political geography who inspired Hitler, had visualized. Ratzel believed that the state is a living creature, with necessities prompting it to expand to annex territories, even if military force is deployed to this end.[2]

There had been extensive discussions in Russian decision-making circles on the concept of the Russian Lebensraum. They pointed out that the principal threat since the fall of the Soviet Union has been the expansion of NATO to swallow the entire region of Eastern Europe, thus coming in to close proximity to Russian borders. Russian cities are within NATO’s firing range.

The Russian Strategy Toward the Caucasus

When looking at the map of Russia and the Caucasus, one finds that Russia — despite some concerns that the United States will draw Georgia toward its sphere — mainly fears the expansion of NATO from the south. From this direction, Russia has always been protected by the Caucasus. It is a rugged mountainous area that does not help in mounting attacks, thus NATO has never considered this option (see Map 1).

Map 1: Russia’s Outlook on the Caucasus as a Lebensraum

The Caucasus region consists of two mountainous chains. The north is more rugged while the south is less rocky to some extent. The north houses Chechnya and Dagestan — both of which contain Islamic separatists which Russia fears and with whom multiple skirmishes have taken place, particularly in Chechnya. Russia lost two wars to Chechnya and it just about won the third one. These Islamic separatists have remained calm until now as Putin took political measures to control these two regions. But, Russia fears that outsiders may enter the fold to help in reorganizing and supporting the separatists to exhaust her, especially after the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan. Moscow fears that Afghan territories could once again turn into a gravitational center, attracting terrorists from the Caucasus and Central Asian regions.

Putin is concerned that the South Caucasus countries (Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan) have broken away from Russian influence as they are now independent states. Russia fears that the South Caucasus countries may form an anti-Russia alliance and that the West, especially the CIA, will back revolts or rebellions in the North Caucasus, paving the way for eliminating the southern barrier and opening up a loophole in the north. Driven by its fears, Russia has maintained an alliance with Armenia, the weakest of the three countries and has complicated its ties with Azerbaijan, a prosperous oil-producing country. As for Georgia, it moved away from Russian influence and placed itself in the US orbit. Therefore, Russia waged a military campaign against it in 2008 given that it is the most acute threat in the south against her.

Moreover, Russia has been suffering in the south because of the long dispute between Azerbaijan and Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh. For over two decades, Azerbaijan avoided a full-blown dispute. But it recently decided, through support from its ally Turkey, to wage a massive attack on Nagorno-Karabakh. The Russians are aligned with Armenia and feel uneasy about the victory of Azerbaijan and Turkey which seeks to become an influential powerhouse in the Caucasus region. As an ally of Armenia, which is a poor former Soviet republic with a populace of less than 3 million, Russia already possesses a military base northwest of Armenia. It sent a 2,000-troop peacekeeping force to Nagorno-Karabakh which will serve for at least five years. The disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh is a pocket of land in Azerbaijan inhabited by the Armenians under the agreement which brought the fighting in the region to an end last year.[4] In the end, it was Russia that helped with the negotiations to end this war. In the meantime, 2,000 Russian troops in Nagorno-Karabakh represent a decisive force. This means that its ally Armenia now has Russian forces in the east of the region and Azerbaijan has Russian forces in the north and west of the region (see Map 2).

Map 2: Areas of Russian Peacekeepers in Nagorno-Karabakh

In reality, Russia took an important step to restore the South Caucasus or at least to have a certain level of control over it. The existence of a major Russian force with a long-term right to stay there will eliminate what would have been a potential threat in the long term. Maybe the presence of US forces in Georgia poses a problem. But given the lack of US offensive intent, it is unlikely that Washington is ready to deploy a significant number of troops to the region. The minimal presence of US training forces in Georgia is something that Russia could possibly live with.

The Russian Strategy Toward the Western Front

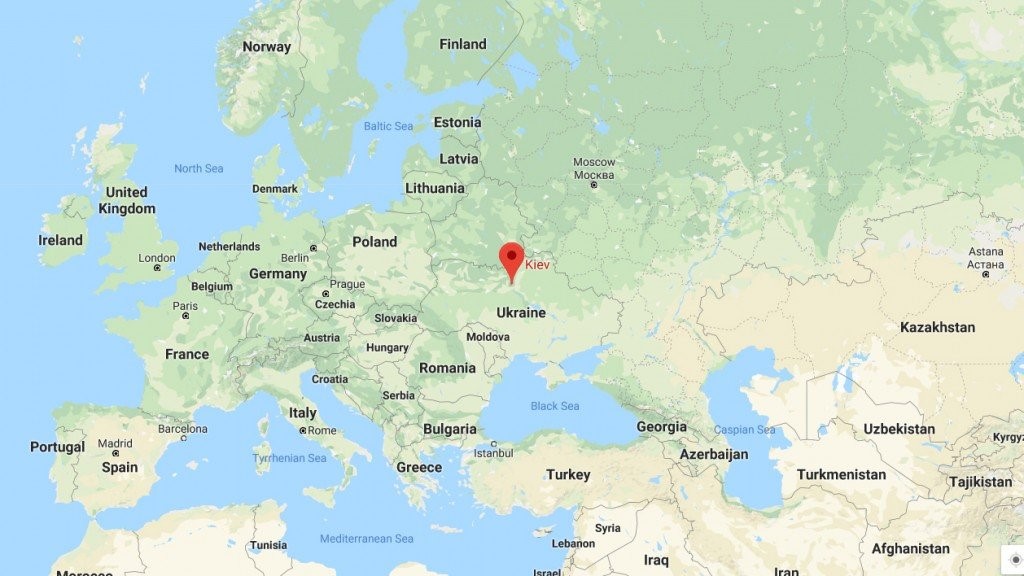

On the western front, a look at the Russian map reveals that NATO is advancing from the West to keep Russia besieged within its borders and prevent it from expanding toward warm waters. Russia is aware that its western flank (Ukraine) has always been the path taken by invaders. Russia still remembers that the invasions led by Napoleon and Hitler happened through crossing this gateway between the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea. Hence, it prefers to keep this region as a buffer zone and a barrier against Western advancements (see Map No. 3). The West perceived it necessary to secure the eastern flank; throughout ancient and modern history it had represented the gateway used by the “Barbarian” invaders to subdue Western cities and extend influence over them. Therefore, through reinforcing the eastern front, the Russian bear can be contained and its expansion curbed.

Map 3: Ukraine’s Geographic Location

No doubt that the West has so far swallowed the whole of Eastern Europe, except two countries: Ukraine and Belarus. If the West moves ahead to expand its influence into these two countries, it will totally deprive Russia of any foothold to the central region of Eastern Europe. Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there were Russian-American understandings, resulting in a tacit agreement with Washington: The United States will not provide Ukraine with massive offensive weapons. In return, Russia will not move large numbers of troops to Ukraine. Neither Russia nor the United States wanted the war. Perhaps each of them wanted Ukraine to be a buffer zone. This is what appeared initially, before things drastically changed.[6]

As to Belarus, it still spins in the Russian orbit. Russia will not accept any other attitude. Belarus is just 400 miles away from Moscow. Poland, which is hostile to Russia and houses some US forces, is located to the west. This poses a major threat to Russia if it fails to keep Belarus spinning in its orbit. The elections in Belarus held this year created an opportunity for Moscow. Though Russian-backed Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko faced dangerous opposition, he won the vote. In exchange for Russian support, Lukashenko is prevented from making any compromises with the West to which Moscow disagrees. He also has to meet Russian military requirements.

On balance, the three Baltic countries (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) continue to pose a threat to Russia due to their NATO membership and because of the alliance’s military units stationed there. Yet, their terrain makes it difficult to wage a full-scale war against Russia. Hence, Russia may be secure in terms of not facing a ground offensive. But of course, it is not immune from aerial and missile attacks.

The Geopolitical Significance of Ukraine in the Russian Strategic Calculus

Political geography focuses on the study of natural and human geography — since both factors are critical to determining a country’s international significance and standing. Ukraine is geopolitically significant mainly due to its location and natural resources. Further, the country is an important linkage point between Eastern and Western Europe through which the best trade routes pass. The global powers represented by Russia and the United States have attempted to exert influence over Ukraine, given that it is one of the main gateways to dominate and control the world. This is backed up by Halford Mackinder’s heartland theory which focuses on the territories deemed to be the heart of the world — Ukraine represents the epicenter of the heart.

Ukraine: Strategic Depth for Russia

In his address before the Russian Federal Council in 2005, Russian President Vladimir Putin said the fall of the Soviet Union was the most devastating geopolitical disaster in the history of Russia. Putin meant that the fall of the Soviet Union had caused Russia to lose its strategic depth which had allowed it to withstand foreign invasions since the 18th century. The Russians cannot accept Ukraine joining NATO. Russia allowed the Central and Eastern European countries as well as the Baltic countries to engage with the West and Western organizations. But Russia embraced an intransigent position toward Belarus and Ukraine (Slavic nations) breaking away from its influence. Ukraine is of particular importance. It represents strategic depth for Russia and serves as a barrier preventing Western expansion. Since the independence of Ukraine, the West has attempted to integrate it into NATO and the European Union, given its geostrategic and economic significance. Russia is adamant that it will not allow Ukraine to join the West if it wants to regain its spheres of influence and restore its standing as a global superpower.

Over the course of history, Russia has always considered Ukraine to be part of its traditional motherland and an essential part of its history despite the cultural differences. During the Soviet era, despite the full control over Ukraine, there had been calls from Ukrainian national elites to seek independence from the Soviet Union. However, Russia was able to repress Ukrainian nationalism until the collapse of the Soviet Union. After its collapse, it was unable to maintain its grip over Ukraine. The latter became an independent state and Russia recognized it in 1997.[7]

In geographic terms, Ukraine has a unique location. When looking at the map of Europe, we find that Ukraine has an important strategic location in Eastern Europe. It is located at the crossroads between Europe and Asia. Ukraine’s unique geographical location lies in the fact that it overlooks the Black Sea. Getting access to the Black Sea allows access to the Mediterranean, which is particularly important for Russian trade and the passage of energy supplies to all parts of the region. Russia cannot cede Sevastopol city or the Crimean Peninsula, the essential base for the Russian Black Sea fleet, allowing it to have a presence in the Black Sea and the Mediterranean (see Map 4). This presence gives Russia greater room for free strategic maritime movement, the ability to carry out strategic deployment and the capacity to transfer forces to its spheres of influence in the Middle East. This means Russia possesses the necessary characteristics/capabilities to be considered as a superpower.

Map 4: Ukraine’s Geography

Russia is aware of the threat posed to its national security if Ukraine joins NATO. Ukraine is the last strategic garrison that separates Russia from the West and its allies. As known to all, the principle of collective defense is one of the key principles of NATO. An attack launched against a NATO member country is considered to be an attack against all the alliance’s members. If Ukraine is granted NATO membership, it will be acutely dangerous for Russia to take any military action in the Ukrainian territories. NATO could also support Ukraine to restore the Crimean Peninsula and wrest full control over the separatist region of Donbas. This would be considered a massive loss for Russia and would diminish its influence, however, it would be a triumph for Washington and its allies. Russia fears that Ukraine joining NATO would open the door for Georgia to follow suit, which would be a severe blow to Russian influence. It would also lead to Russia being besieged militarily and pose an aerial and missile threat to its security.

To Russia, the West’s entrenchment of its interests and clout in Ukraine means its exertion of influence over the entire northern part of the Black Sea and the Crimean Peninsula which has strategic and historical importance. As Turkey, the West’s ally, sits on the southern coast of this sea — and Romania and Bulgaria on the western coast and Georgia on part of the eastern coast — Russia’s presence in this warm sea will be limited to only part of the eastern coast. The Black Sea is strategically important for Russia as it allows the safe and swift movement of its naval fleets. With Russia’s limited presence in this sea, it will no longer have the aforementioned strategic benefits. This will curb the movements of the Russian navy toward the Mediterranean. Russia has a foothold in Syria and pockets of influence in in Libya and some North African nations.

Russian Policies to Contain Ukraine

Immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine maintained traditional relations with Russia. In 1994, Leonid Kuchma was elected as the new Ukrainian president who hoped to maintain good ties with Russia. In 2003, he approved a Russian proposal to create “a common economic zone” with Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan. In 2004, the Russia-backed candidate Victor Yanukovych won the presidency. Shortly afterwards, the Orange Revolution, staged by the supporters of the candidate backed by the West Viktor Yushchenko, broke out. This revolution forced the election results to be reconsidered, resulting in Yushchenko being declared the winner. Yushchenko’s victory triggered a Russian crisis of confidence, with Moscow believing that the Orange Revolution was instigated by the CIA to weaken Russian clout and disentangle its connections with its neighbors.

Russia is always concerned about foreigners infiltrating its neighboring Eastern European countries. This not only includes the expansion of Western political or military clout into these countries but also Western cultural infiltration. Russia deems the latter to be a dangerous Western policy to move the Eastern European countries away from its clutches and make them embrace liberal ideas which are despised by President Putin. He has always said that liberal ideas reflect a culture that goes against Russian social and traditional values. He has also warned against the moral decadence that liberal ideas could lead to.

At the intelligence level, Russia has been working through the use of soft power to win over Ukrainian officials and for them to partake in elections. In 2010, Moscow succeeded in supporting its candidate Yanukovych. He won the presidential election and resumed relations with Russia. His administration extended Sevastopol port’s lease agreement with Russia and reduced ties with the European Union. But the protests demanding alignment with the West quickly reemerged, which prompted Yanukovych to resign from office amid Russian astonishment.

A new Ukrainian government was installed. The Western-backed Oleksandr Turchynov was elected as Ukraine’s president. Russia refused to recognize Turchynov’s government. Then in 2014, the Ukrainians elected Petro Poroshenko, who continued his escalatory and harsh rhetoric against Russia. Relations between Russia and Ukraine went downhill. Russia realized that diplomacy did not achieve its objectives in Ukraine and that military force must be deployed and a fait accompli must be imposed that enhances its geopolitical standing. Thus, Russia waged a military campaign leading to the capture of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula in 2014 — the first time a European country annexed territory belonging to another country since World War II.[9]

In a speech he delivered in 2014 before the Duma, Putin made the claim of Russia’s historical right to Ukraine. He said, “In people’s hearts and minds, Crimea has always been an inseparable part of Russia. This firm conviction is based on truth and justice and was passed from generation to generation, over time, under any circumstances, despite all the dramatic changes our country went through during the entire 20th century.”

He added: “Our task was not to conduct a full-fledged military operation there, but it was to ensure people’s safety and security and a comfortable environment to express their will.”[10]

Putin and Russian state-run media outlets have repeatedly accused Ukraine of mistreating people who have Russian origins, and reiterated the demand to reintegrate the Crimean Peninsula into the Russian motherland. The aforementioned speech came days after the people of Crimea demanded a referendum to support its return back to the Russian motherland and weeks before violence started in eastern Ukraine between Russian-backed forces and the Ukrainian army.

The annexation of the Crimean Peninsula and the outbreak of revolts in eastern Ukraine in 2014 created the justification for the new Ukrainian ruling coalition to turn to NATO. It demanded to be part of NATO’s defense umbrella to deter Putin’s ambitions which go beyond the Crimean Peninsula. As for Moscow, the Ukrainian leadership merely entertaining the idea of letting a former Russian satellite state with much geographic and economic importance joining NATO would be an unacceptable scenario and reflects the abject failure of Russia’s broader strategy.

Russia is aware that NATO’s expansion eastwards toward its sphere of influence will undermine its ability to defend itself against ground, air and naval incursions. The Russians began to re-read what the strategic theoretician Halford Mackinder wrote, “Whoever controls Eastern Europe controls the Heartland. And whoever controls the Heartland controls the World Island. And whoever controls the World Island will soon rule the world.”[11]

Russia is aware that Ukraine is the heart of Eastern Europe and that NATO’s outreach to it and placing it under its security and defensive umbrella is a stab in its back and a move that will thwart its chances of becoming a global superpower.

In 2019, comedian-turned politician Volodymyr Zelenskyy won the Ukrainian presidential election at the expense of President Poroshenko. Zelenskyy was no less hostile than his predecessor when it came to relations with Russia. His victory symbolized that the majority of the Ukrainian people are fed up with Russia’s hostile behavior and they want to turn to the West, not to Russia. Hence, Zelenskyy did not bow to Russian blackmail and called for a full Russian withdrawal and the disarmament of all its illegal military formations in eastern Ukraine. He advanced the process to join NATO and the European Union. The West, particularly the United States, rushed to provide Ukraine with cutting-edge weapons and military training, putting more pressure on Russia.

Russia’s Geopolitical Achievements From Invading Ukraine

Have the Russians Achieved Their Goal in Ukraine?

Putin is intent on establishing the new Russia through exploiting the so-called “frozen conflicts;” the differences within the Eastern European countries neighboring Russia — and using these conflicts as an entry point and justification for Russian intervention and expanding Moscow’s clout beyond Russian borders. Over the past three decades, Moscow has thrown its weight behind a pro-Russia regime in the separatist region of Transnistria in Moldova. It has also backed separatist governments in South Ossetia and Abkhazia in Georgia, two countries with a large number of Russian-speaking people. The existence of Russian-speaking people presents the Kremlin with a justification to interfere in the affairs of other countries. The Kremlin claims to act as the guardian of the Russian-speaking people against their integration into the West and protect them from embracing Western liberalism. Moreover, there are some who argue that Russia uses the Russian-speaking people as a bridgehead to expand its geopolitical sphere.

Russia has argued that NATO’s expansion eastwards damaged international relations with the West after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and this must be rectified now. The Kremlin wants, at all costs, to end the expansion of NATO eastwards — especially in the sphere of its traditional clout — and remove US nuclear weapons from Europe. Russia also wants to ensure that Belarus, Georgia, and Ukraine will never belong to a military or an economic bloc other than one that is dominated by Moscow and that it will continue to have the final say over foreign and security policy in the aforementioned countries. These three countries, according to the Russian point of view, should recognize Moscow’s sovereignty over their political decision-making as a fait accompli. According to the Russian point of view, Moscow should possess an exclusive sphere of influence in Eastern Europe and the South Caucasus, even if military force must be deployed to secure its interests in these regions.

In its military campaign against Ukraine, Russia announced that it had finished the first stage of its campaign, claiming it had achieved the goals set for the first stage. Before examining to what extent the Russian goals had been achieved, we should ascertain whether Russia has set an “end state” that it aims to achieve by the end of the war or if it has identified a set of goals which it seeks to achieve. The end state — as I see it — can best be defined as “ which point are we at now? And where should we be by the end of the war?” This means that policymakers should paint a precise picture of the geopolitical situation which they want to achieve by the end of the war to their military and civilian leaderships.

Prussian military thinker Helmuth von Moltke (1800-1891) advised war commanders against starting a war without having the desired outcomes visualized in their minds. He had a maxim which became the basis of one of the most important strategic planning rules. Addressing political leaders, he said, “Don’t start a war before imagining the ends in your mind and you have the ability to win it.” The role of field commanders and war generals is important: they should know what the political leadership specifically wants from the war and the end state which it wants to achieve.

Senior field commanders should start from the desired outcome to develop the necessary war plan and evaluate the needed military capabilities to secure victory. There is no such thing in military science as starting a war and determining the final outcome later. Military commanders need from the very beginning to outline the battle scenario they want to wage and execute it via war games before entering the battle. It is easy to start a war but it is difficult to control it and its consequences after the first spark breaks out.

Neither the final outcome nor what Putin intended to achieve by the end of Russia’s military campaign against Ukraine was unknown. Despite some victories, it remains unclear whether there is a well-defined Russian military strategy. This is also true of US operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, with US political and military planners unsure of the final outcomes. They did not even prepare a comprehensive military strategy over the course of the wars, which led to America’s failure to a great extent, prompting Washington to look for what it called a strategic exit. The exit plan is mostly executed when facing difficulties and setbacks in achieving the visualized end outcome and wanting to save face in front of domestic audiences and the world.

In the War Proclamation Address before the nation on February 24, Putin specified his goal regarding the special military operations: to strive for the demilitarization and denazification of Ukraine.[12] In fact, it is hard to convince us that this stated objective reflects the final goal of Putin’s war against Ukraine. The aim behind demilitarization is clear and achievable to a great extent because of Russia’s massive firepower. However, the process of denazification could be extremely difficult, given that Nazism is an ideology. It is not something material, logical or visible. Those embracing this ideology do not have marks on their bodies identifying them as Nazis. There are no clear structures representing Nazism nor are there specific leaders championing Nazism.

Putin’s remarks can be understood in the context of political rhetoric — not to clarify the ultimate goal of the war but to disseminate some sort of propaganda at home and abroad — painting a bright picture to legitimize the act of war. In doing so, politicians aim to secure the highest possible level of popular and official sympathy. The real goals of the war are usually concealed. They are only revealed to war generals or national security officials for them to develop plans and strategies to achieve the desired end.

In the face of such ambiguous remarks by politicians about the goals of war, observers and analysts find themselves prompted to conclude war objectives through tracking the course of military operations, the positioning of forces, the directions of military movements, the categories of weapons used and the size of the forces deployed. If we project the aforementioned considerations onto the Russian invasion of Ukraine, we will find — in my opinion — that Putin’s estimated and desired outcome is the ouster of the Ukrainian government and the installation of a pro-Putin government that agrees to amend the Ukrainian Constitution, stipulating that Ukraine shall be armed on a limited scale, neutral and not a NATO member.

It is believed that so far Putin has failed to deliver on Plan A — achieving the supposed end outcome as mentioned. But the Russian defense minister called it “the first stage.” He also said that the Russians have now begun the second stage, which, according to military planning science, is nothing but Plan B. Under this plan, instead of taking control of Kyiv and toppling the government, which is hard to achieve, Russia seeks to take control of Donbas, and enhance the independence of Donetsk and Luhansk while continuing negotiations with the Ukrainian government to play on the element of time.

All the aforementioned is related to the end outcome. As for the strategic objectives of the Russian military campaign, the Russian Defense Ministry did not clearly disclose them. However, it can be concluded that the strategic objectives include: first, weakening the Ukrainian political leadership and forcing it to make concessions; second, turning Ukraine into a neutral state and not allowing it to join NATO; third, defeating the Ukrainian armed forces and weakening them so that they do not pose a threat to Russia or to the separatists in Donbas; fourth, toppling the capital Kyiv; and finally, separating Donbas from Ukraine by creating two independent republics affiliated with Moscow.

The Extent of Russia’s Achieved Strategic Objectives

Two months have passed since the start of the Russia-Ukraine war. Despite the Ukrainian resistance, Russia has managed to achieve some of its strategic objectives. However, Russia has fallen short of scoring the geopolitical points that it aspired to achieve. As to the first and second objectives — weakening the Ukrainian government so it yields to the conditions dictated to it — so far, the Ukrainian political leadership is still effective and is faring quite well when it comes to managing the crisis. The Russians have so far failed to liquidate members of the Ukrainian government. The survival of the Ukrainian government can be construed as Russia’s inability to eliminate its members or a desire to keep them alive to finalize the negotiations but with a weakened resolve, moral defeat and their isolation from the Ukrainian people. Maybe the Kremlin seeks to merely put pressure on the Ukrainian government so that it accepts an agreement to ensure that Ukraine remains neutral and pledges not to join NATO. So far, the negotiations are still going on and the Russian demands, particularly regarding Ukraine’s neutrality, remain firm.

With regard to the third objective, disarming Ukraine, the Russian army has achieved a considerable portion of this objective through the near-total destruction of the Ukrainian military infrastructure and significantly reducing the combat capabilities of the Ukrainian armed forces — particularly the air force and the air defense force. Until mid-April 2022, 123 out of 152 Ukrainian fighter jets, 77 out of 149 helicopters and 152 out of 180 medium and long-range air defense systems were destroyed. Furthermore, the naval force was totally destroyed, and all units of Ukraine’s ground assault force suffered heavy losses.[13] Meanwhile, Russia imposed aerial control and reached the extent of what is known as full air sovereignty over the airspace of the war theater.

When it comes to capturing Kyiv, it will remain a strategic objective for the Russian army — though hard to achieve at the present stage. This is because taking the capital is always the biggest objective, which if successful, makes securing the other military objectives much easier. The capital is always the symbolic heart of a country, as it represents the political functioning of the Ukrainian state. The fall of the capital dampens national morale, causing the rest of the cities to fall, securing victory for the invaders. Until now, the Russians have failed to take control of Kyiv, a city with a populace of 3 million, despite being only 30 kilometers away from it due to the powerful Ukrainian armed resistance and Russia’s fear of attracting negative public opinion against its war in case it pursues a scorched-earth policy resulting in a bloodbath. But the chief reason is Russia’s fear of sliding into urban warfare which it experienced before without any significant success. In fact, the Russian army’s incursions into Grozny in 1994 and 1999 and its involvement in Aleppo in 2015 were difficult. Thus, it seems that the poor experience of urban warfare is still fresh in Russia’s military memory. Instead of direct attacks on cities, the Russians this time chose a different military approach: placing cities under siege, encircling resistance pockets and isolating them from civilians, attacking cyberspace and communications networks to deprive the government of the ability to communicate with, inspire, and guide the people. This is in addition to bombing key facilities in cities and military infrastructure as well as opening up safe shelters for people to vacate to until cities surrender.

After completing most of the first stage of its military campaign in Ukraine, which can be considered as Plan A, Russia will focus on its bigger strategic objective or what it calls the second stage: fully liberating Donbas in eastern Ukraine, considered to be part of Plan B. The Russian Defense Ministry said the separatists backed by Russia now control 93 percent of Luhansk and 54 percent of Donetsk. The Russian Defense Ministry also announced Russia’s control of Mariupol port after liberating it fully from the militants of Ukraine’s Azov Battalion.[14] Mariupol is Moscow’s chief target in Donbas since it will make it easier for it to link its forces deployed in Crimea with those stationed in Donbas’ separatist areas. Taking control of Mariupol marks an important step toward complete control of the largest and most important port on the coast of the Sea of Azov. Wresting control over it means a strong economic capacity for Donetsk and Luhansk, especially in the field of coal and minerals exports. Depriving Ukraine of controlling it will mean undermining its economic capabilities, especially grain exports.

Beyond the abovementioned strategic objectives, there are ephemeral gains which Moscow managed to make. Among the gains is the sympathy displayed by several countries, especially in the Arab world and Africa — or what the West calls the Third World. Russia has launched media and diplomatic campaigns to promote its war against the liberal, expansionist and draconian West, which according to Moscow has turned Ukraine into factories of epidemics and spread them all over the world. Russia has significantly succeeded in this despite the strong Western propaganda that supports the Ukrainian narrative of the war. But this propaganda has lost its credibility, especially among the peoples in the Arab world, who have grown weary of the Western methods of influencing public opinion. Therefore, Arab media outlets resorted to Russian media outlets in search of the truth instead of Western media outlets, which have lost credibility.

In fact, Moscow managed to gain sympathy for its war from many Arab and African countries. The Western world rose up in unison to denounce and decry the Russian war against Ukraine and provided Kyiv with weapons and imposed economic sanctions on Russia. But Africa and the Middle East displayed sympathy with Russia. This confirms two facts: first, Russia has succeeded over the past two decades in mending ties with the African and Middle Eastern countries and forging partnerships, whether in energy or in the military fields. Second, it seems that a large number of Middle Eastern countries are fed up with US interventionist policies and no longer feel that Washington nor the West in general are credible when it comes to honoring their commitments to support peace and stability in the region, especially when they have done little to exert pressure on Iran to stop its proxy war projects. The Gulf states, which have long depended on the United States for protection, now believe that this security umbrella has loopholes. Gulf diplomats and others across the region hope their neutral position on Ukraine sends a message to Washington that “if we cannot depend on you, you cannot depend on us.”[15]

It seems that from now on, the Gulf states in their foreign policies will give precedence to their interests, commit to neutrality and diversify their alliances. China and Russia have become two essential partners for the Gulf states. The interests between these two major world powers and the Gulf states are much more significant compared to the mutual interests between the Gulf and the West, especially in the economic and energy fields. Even the military field is witnessing more interactions between the Gulf states and the two aforementioned major world powers. Regardless of the level of US political pressure on Saudi Arabia to increase the share of its oil production, Riyadh will be keen to maintain relations and joint understandings with Russia. It seeks to maintain a balanced policy on energy that first serves its interests and second achieves the interests of OPEC+ members, a bloc in which Russia is a major member.

On February 25, the UAE shocked the United States and the West when it abstained from voting on a UN Security Council resolution condemning the Russian military operation in Ukraine. Moreover, the Arab League statement issued three days later made neither implicit nor explicit mention of Russia and although Egypt and the other Gulf states voted in favor of the General Assembly proposal in this matter, the officials of these countries argued that it is not their war and they do not have any official alliances with either of the parties involved in the conflict.[16]

Among the manifestations of sympathy with Russia was when most of the Arab countries abstained from voting on a resolution to suspend Russia’s membership to the UN Human Rights Council. Abstaining from voting reflects a position that is close to rejection or is indicative of reservations regarding the resolution. Arab countries are hesitant about issuing a resolution that condemns Russia before sending a committee to investigate the crimes committed in Ukraine as was the case in Syria, Gaza and Lebanon. They do not want to escalate the situation in a way that does not serve the mediation efforts led by the Arab League.

Anyway, when looking at the European map, one will realize the geostrategic significance of Ukraine, which lies in the fact that it is located at the heart of the European continent. Whoever wins Ukraine on its side as an ally will be closer to pulling the geopolitical strings in Europe. This cannot be untrue given Ukraine’s massive and unique natural resources. It is bigger than France in terms of area and at the crossroads of important maritime and overland routes, where the East and West and the North and South converge.

In the end, Ukraine will remain one of the most important geopolitical arteries for Russia in terms of its strength, survival, and recognition as a global power. The Russian military campaign will continue until Ukraine becomes — at best — a pro-Russia country again or Moscow at least gets guarantees that Ukraine will remain neutral and will not join NATO. However, Russia will not withdraw from Ukraine without ensuring that Donbas is fully liberated and under its control. Surely, Russia’s expected gains will not come without economic consequences for it, especially in the short term. But Putin is betting that the cost-benefit calculus will swing in his direction, and he will make significant geopolitical gains.

[1] Aqel Abbas, “Lebensraum and Russia’s Dreams of Reclaiming a Glory that Will Never Return,” Al-Nahar Al-Arabi, March 1, 2022, accessed March 31, 2022, https://bit.ly/3iPe6TB. [Arabic].

[2] “The Lebensraum Theory of Countries,” Ra2ej,November 24, 2019, accessed April 2, 2022, https://bit.ly/3vxCZcp. [Arabic]

[3] George Friedman, “Russia’s Search for Strategic Depth,” Geopolitical Futures, 17 November 2020, accessed 12 April 12, 2020, https://bit.ly/3xmuS4X.

[4] “Russian Military in Armenia Reinforce Areas Near Azeri Border,” EURACTIV, 4 May 2021, accessed April 17, 2022, https://bit.ly/3KSPENw.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Friedman, “Russia’s Search for Strategic Depth.”

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Russia blocking of Black Sea would be ‘unjustified’: NATO,” Bangkok Post, April 17, 2021, accessed May 12, 2021, https://bit.ly/3M7flLa.

[9] Christopher Schmidt, “Evaluating Russia’s Grand Strategy in Ukraine,” E-international Relations, July 6, 2020, accessed March, 21, 2021, https://bit.ly/36uOE30. [Arabic].

[10] Ibid.

[11] Dalal Mahmoud, “The Ukrainian Crisis: The Real Objectives of Russia and the United States,” The Egyptian Center for Thought and Strategic Studies, February 22, 2022, accessed March 21, 2022, https://bit.ly/3wnQpdb. [Arabic].

[12] Frank Ledwidge, “Ukraine War: What Are Russia’s Strategic Aims and How Effectively Are They Achieving Them?” The Conversation, March 2, 2022, accessed April 4, 2022, https://bit.ly/3u5Qell.

[13] Elena Teslova, “Russia Has Achieved Main Initial Goals in Ukraine: Defense Chief,” Anadolu Agency, March 29, 2022, accessed April 4, 2022, https://bit.ly/3wZR2Kn.

[14] “Russia: Most of the First Stage of the ‘Ukraine Campaign’ Is Completed and Now the Focus Is on Donbas,” Al-Sharq Al-Awsat, March 23, 2022, accessed April 4, 2022, https://bit.ly/3DCypNK. [Arabic].

[15] “The Economist: How Does Russia Win the Sympathy of Africa and the Middle East in Its War on Ukraine?” Al Jazeera, February 14, 2022, accessed April 18, 2022, https://bit.ly/3rysULa. [Arabic].

[16] Ibid.