Introduction

Syria-Israel relations were governed by a security arrangement rooted in the 1974 disengagement agreement. This arrangement ensured relative calm along the shared border, with minimal security threats or risks, until the onset of the Syrian uprising in 2011. The ensuing developments generated a complex and evolving security environment that required Israel to recalibrate its approach to safeguard stability along its northeastern frontier. Over the 14 years of the conflict in Syria, Israel succeeded in maintaining a delicate balance amid competing domestic and global actors. It also managed to mitigate emerging security risks through a combination of military interventions and political maneuvers.

Later, the October 7, 2023 attacks marked a watershed moment for Israeli national security, prompting Tel Aviv to initiate a full-scale military campaign against the Gaza Strip. This escalation, in turn, led the various factions within the so-called Axis of Resistance to operationalize the strategy of “unity of arenas,” manifesting in a series of coordinated military engagements. These confrontations dealt significant blows to Iran and Lebanese Hezbollah, constraining their strategic reach in Syria. These setbacks, coupled with Russia’s disengagement from Syria due to its preoccupation with the conflict in Ukraine, precipitated the rapid collapse of the Assad regime. The disintegration of this regime effectively dismantled the longstanding security arrangement between Syria and Israel.

In response to these developments and motivated by heightened anxieties following the October 2023 attacks, Israel undertook a series of aggressive measures to safeguard its national security. Key indicators of a shift in Israel’s rules of engagement in the transition from the Assad era to the post-Assad phase included targeting the new Syrian authorities, expanding territorial control, bypassing the UN’s role in security-related arrangements and intervening in the formation of the new Syrian government in a manner favorable to Israeli security interests.

Given Syria’s current transitional state and the layered complexities associated with the broader conflict, in which the Israeli dimension has emerged as a critical determinant, this study analyzes Israel’s strategic posture in Syria from a geographic-security standpoint. It proposes a tripartite model comprising three concentric security spheres: the sovereign circle, the direct security circle and the indirect security circle. The study defines each of these spheres, delineates Israel’s specific objectives within them and examines the mechanisms Israel employs to realize its strategic aims. Additionally, it explores the challenges Israel faces in operating across these distinct but interrelated security domains.

Syria From Israel’s Security Perspective After October 7, 2023

The border between Syria and Israel is the shortest among Israel’s neighbors, measuring no more than 80 kilometers. Nonetheless, it remains the most intricate, primarily because of Israel’s occupation of the Golan Heights and the resulting political and military consequences — impacted by ongoing developments within both countries and the broader region. The demographic landscape on either side of the border, especially the concentration of the Druze minority, adds another layer of complexity. This is further intensified by the geographical proximity of Damascus, the Syrian capital, which lies just 70 kilometers from the border. Such proximity renders any military arrangements with sovereignty implications more likely to reflect a zero-sum dynamic in how both sides — Syrian and Israeli — approach crisis management.

From the standpoint of Israeli national security, Syria can be conceptually divided into three zones of security significance, encompassing both direct and indirect dimensions. The Golan Heights — comprising both the Israeli-occupied portion and the adjacent Syrian side — constitute the first and second of these security circles. The first security circle refers specifically to the sovereign border region within Israeli territory, which is home to both Druze communities and Israeli settlers. On the opposite side lies the direct security zone, which includes the UN-monitored disengagement area as well as Syria’s Quneitra Governorate.

The third zone — the indirect security circle — encompasses the rest of Syrian territory, which, as a neighboring state, carries strategic weight in Israel’s broader security calculations. Within this framework, the position of Damascus becomes particularly noteworthy: its distance from the Israeli border is minimal, with the closest point measuring no more than 50 kilometers. This geographical proximity places the Syrian capital squarely within Israel’s direct security circle. The same logic applies in reverse — from the Syrian perspective, the capital also lies within the sovereign security circle, making it central to Syria’s national defense posture.

This geographical reality reflects a broader strategic dilemma often faced by peripheral capitals — those located near national borders — unlike central capitals situated deeper within a state’s territory. Peripheral capitals, lacking natural defensive depth, face inherent vulnerabilities that complicate efforts to ensure national security.

Over the course of nearly 14 years of the Syrian uprising, Israel’s approach to safeguarding its national security was visibly aligned with the previously outlined classification, particularly within the direct and indirect security spheres. In the direct security sphere, Israel consistently sought to prevent the consolidation of any substantial or powerful presence of armed groups along the border area — whether from opposition factions or militias affiliated with Iran and Hezbollah. It routinely targeted attempts at entrenchment in this zone and maintained close surveillance over the battles unfolding in the corridor stretching from the Damascus countryside to the Quneitra countryside.

This strategy was partially facilitated by the demographic composition of the area, including several Druze towns that largely refrained from offering a social base for either side in the conflict. As a result, the Syrian regime was able to reestablish control over its positions in Quneitra Governorate following the 2018 reconciliation agreements and continued to observe the terms of the 1974 disengagement agreement.

In contrast, within the indirect security sphere — comprising Syria’s more distant northern, eastern and western governorates — Israel chose not to intervene in the clashes among local and external actors. Instead, it concentrated its efforts on neutralizing threats deemed directly relevant to Israeli security. The Israeli Air Force carried out hundreds of precision airstrikes, targeting advanced missile consignments destined for Hezbollah and eliminating high-ranking figures from both Hezbollah and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.[1]

The events of October 7, 2023, however, came as a profound shock to Israel, exposing critical vulnerabilities in its national security doctrine, which had traditionally centered on deterrence as its foundational principle. The failure of this model prompted the Israeli military to undertake a fundamental reassessment of its strategic framework. Since then, Israel has adopted an entirely different operational posture — discarding prior rules of engagement and entering into direct military conflict with Iran, while also delivering exceptionally forceful strikes against Hezbollah.

These transformations, combined with other contributing factors, played a role in catalyzing change within Syria. The aftershock of October 7 was particularly evident in Israel’s behavior following the sudden collapse of the Assad regime. Deep concerns emerged over the possibility of a similar surprise attack unfolding along the Syrian border, particularly given that Israeli intelligence failed to foresee the regime’s rapid downfall, which occurred within days. As a result, Israel’s response in Syria was shaped by a sense of acute shock — mirroring the reactive posture it had adopted in Gaza after October 7, 2023.[2]

In the Syrian context, Israel’s occupation forces adopted a markedly offensive posture, initiating large-scale, diverse and swift strikes despite the absence of any immediate threat. These actions were largely precautionary, motivated by fears of being subjected to similar attacks in the short or medium term — concerns that were explicitly addressed in the final report of the Nagel Committee submitted to the Israeli Defense Forces. The military leadership, in line with the committee’s recommendations, called not only for the preservation and enhancement of Israel’s defensive capabilities but also for embracing a doctrine of offensive and preventive operations. This approach entails leveraging the strength of the Israeli military not merely for defense, but to proactively neutralize threats either as they emerge or even before they materialize.

In the aftermath of October 7, a growing consensus has emerged that deterrence alone is no longer sufficient; rather, there is now a perceived imperative to adopt preemptive action as a strategic necessity.[3] These Israeli strikes also convey, in one sense, a form of rapid decisiveness — achieving their intended goals within a very short timeframe and without provoking any meaningful retaliation from adversaries.

Alongside these operations, Israel publicly outlined a set of objectives it intends to pursue across all defined security spheres. These include various components of its traditional military doctrine — deterrence, early warning and rapid resolution — all of which Israel now seeks to restore and reinforce across multiple fronts. The successes it has secured against its adversaries thus far are being leveraged to this end. These themes are further explored in the subsequent section.

Israeli Objectives in the Syrian Security Spheres Following the Fall of the Assad Regime

The collapse of the Assad regime and the subsequent rise of the opposition to power aligned with certain Israeli interests — chief among them, the elimination of Iran’s presence in Syria and the resulting curtailment of Iranian regional influence. Of particular significance was the disruption of the overland supply corridor from Iran to Lebanon via Iraq, a key logistical route for Iranian support to Hezbollah. However, the fall of the Assad regime also led to the breakdown of the prior security arrangement that had governed the Israeli-Syrian frontier.

In response, the Israeli occupation has moved to pursue a series of strategic objectives aimed at both restoring key elements of the status quo that prevailed under Assad and extracting additional advantages from the unique circumstances of Syria’s transitional phase. These efforts are also driven by a desire to avert the emergence of a security situation comparable to the surprise attack on Israel in October 2023.

Israel’s most critical objectives — and the instruments it has employed to advance them — within its three delineated security spheres can be summarized as follows:

Objectives and Tools in the Sovereign Security Spheres

The attacks of October 2023 primarily targeted Israeli settlements and military installations situated along the border with the Gaza Strip. Meanwhile, the areas near the Lebanese border experienced some of the most intense clashes between the Israeli military and Hezbollah, which referred to its involvement as part of the “support battle.” These hostilities forced the evacuation of settlers from northern border regions. A majority of the resulting security incidents — including infiltration attempts and exchanges of gunfire — were concentrated along the Israeli-Jordanian border, prompting the Israeli military to respond by enhancing security infrastructure, including the construction of a new barrier.

From this vantage point, Israel continues to view its border areas — especially those adjacent to Syria — as among the most susceptible to emerging security threats.[4] Consequently, ensuring the security of settlements in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights has become a central priority. The area has remained relatively stable, owing to Israel’s control, the absence of hostile activity within the local environment and the deployment of UN forces on the Syrian side of the border. As a result, security arrangements had largely remained within conventional frameworks.

However, the collapse of the Assad regime marked a pivotal shift. In response, the Israeli army bolstered its military posture in the Golan Heights by establishing a specialized rapid intervention unit deployed within the occupied Syrian Golan Heights. The unit’s primary mission is to prevent, if necessary, any assault on Israel resembling the Hamas-led incursion of October 7, 2023. This elite unit maintains full operational readiness, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, regardless of circumstances. It is composed of carefully selected personnel from Israel’s top military and intelligence units.[5]

Simultaneously, Israel’s defense establishment initiated the construction of a comprehensive land barrier along the Syrian border. This new structure is to include a dual-layer fence, supplemented by earthworks and trenches, and will expand upon the current fencing with advanced surveillance technologies and intelligence-gathering systems. The completed barrier is projected to span 92 kilometers along the Israeli-Syrian frontier. The conceptual foundation for this initiative stems from lessons learned following the breach of Israel’s southern wall by the al-Qassam Brigades on October 7, 2023.[6] In tandem with these defensive measures, the Israeli military conducted a large-scale training exercise designed to simulate a rapidly deteriorating security environment in the Golan Heights,[7] reflecting the seriousness with which it views the evolving strategic landscape.

Objectives and Tools in the Direct Security Sphere

The objectives of early warning systems are highlighted within the immediate security zone, which grants the Israeli army greater capability to defend the sovereign security perimeter first and foremost, as well as Israel’s overall security. Accordingly, the Israeli occupation army modified its rules of engagement to allow greater flexibility in carrying out preemptive strikes against military targets inside Syria, without the need for large-scale ground operations. This approach is viewed as part of Israel’s deterrence strategy aimed at reducing long-term security risks.[8] Based on this strategy, the Israeli army expanded the buffer zone inside Syria in order to prevent any attacks on settlements within the occupied Golan Heights. The Israeli army began this operation just weeks before the fall of the Assad regime. On September 22, 2024, it opened corridors along the border in the buffer zone controlled by the UN peacekeeping force in southern Syria, UNDOF, and began removing landmines. A few days later, an Israeli army brigade, supported by tanks and heavy machinery, advanced 300 meters into Syrian territory. The operation included paving a new road, digging trenches and establishing fortifications and new observation points near the border. This move was justified at the time as a way to facilitate future Israeli ground operations on Syrian territory along the border if necessary, and to counter plans by Iran-aligned armed groups based in Syria to launch a ground invasion similar to the events of October 7 in the area of the Golan controlled by Israel.[9] Following the fall of the Assad regime, the Israeli army quickly seized control of the buffer zone previously occupied by UNDOF, which spans 145 square miles. The Israeli army also established new positions inside Syria, built roads to access them, dug trenches and deployed hundreds of soldiers there.[10]

One of the most significant Israeli measures within its new security framework has been the move to assert control over the summit of Mount Hermon, from which Israel withdrew 50 years ago as part of the 1974 disengagement agreement. This mountain holds immense strategic value due to its commanding elevation overlooking Damascus. Its height makes it an ideal natural observation post, offering the capability to monitor both military and civilian movements across surrounding territories. The summit’s elevation also makes it suitable for the deployment of advanced radar systems and early warning stations, which would provide Israel with a marked intelligence advantage and enable timely alerts against potential aerial or ground attacks. Retaining a presence on the summit would naturally serve Israeli security interests and could facilitate future control of the position.[11] Despite these strategic benefits, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has gone further, demanding that the Syrian government demilitarize all areas extending from southern Damascus to the capital itself.[12] Such a demand is highly controversial, as it contradicts the basic principles of national sovereignty and is unlikely to be accepted by any sovereign state.

Adding to the ambiguity, Israeli public statements have been inconsistent — oscillating between suggestions of temporary control pending the establishment of security guarantees and indications of a potential long-term or permanent presence. Moreover, Israeli officials have stated that Tel Aviv requires a buffer zone extending 15 kilometers into Syrian territory to ensure that no future regime loyalists or allied forces will be positioned to launch missile attacks against Israel. Beyond this buffer zone, Israel has also expressed the need for an extended zone of influence reaching up to 60 kilometers inside Syrian territory. This would enable Israel to maintain intelligence dominance in the area, with the objective of detecting and preempting the emergence of any future security threats.[13]

Beyond the buffer zone it seized, Israel imposed a set of conditions governing the military and security presence of the emerging Syrian authority in the surrounding areas. These conditions included the confiscation and destruction of heavy weaponry, as well as a ban on the establishment of any military positions near the border. Within this framework, Israeli forces permitted limited Syrian army activity in the form of police operations in towns located in the northern Syrian Golan Heights, approximately 30 kilometers from the border. At the same time, Israel asserted that its own military forces had full freedom of movement through these towns en route to nine newly constructed settlement outposts, established by the Israeli military inside Syrian territory. According to Israeli assessments, this area has now been designated a “safe zone” under its control.[14]

In parallel, Israel leveraged its purported protection of the Druze minority to pursue broader strategic and political objectives. Specifically, it aligned with the demands of Hikmat al-Hijri in Suwayda, who called for a distinct political and administrative status for the Druze community. By doing so, Israel aimed to advance multiple goals — among these, a domestic political objective of Netanyahu’s government: to secure greater support from the Druze minority within Israel in the upcoming elections. The coalition hopes that demonstrating solidarity with Druze populations in Syria will enhance its appeal among Israeli Druze voters.[15]

Israel used soft power to win over segments of the Syrian Druze population, including organizing visits to Israel in March and April 2025 and offering limited humanitarian assistance — tactics designed to exploit Syria’s dire economic conditions and deteriorating living standards.[16] However, Israel’s engagement was not confined to soft power alone. In the wake of the Sahnaya events in late April 2025,[17] it employed hard power tools to signal the seriousness of its commitment to Druze-related policies.

Moving beyond surveillance and political messaging, Israel launched airstrikes on Ashrafiyat Sahnaya and other locations, officially describing the attacks as “warnings.” Notably, one of the missile strikes landed near the presidential palace in Damascus less than 24 hours after a ceasefire agreement was signed between the Syrian government and Druze representatives. This act was rich in symbolism: a deliberate message that Israel does not acknowledge the full legitimacy of the transitional government and that any political resolution that fails to consider Israeli interests or border security concerns remains vulnerable to disruption.[18]

To reinforce this message, Israel adopted a similar approach during the Suwayda unrest in July 2025. The Israeli air force conducted a series of strikes targeting Syrian government forces in Suwayda military installations on the Thala and Shaqrawiya roads in its countryside, and areas near the 52nd Brigade in al-Harak in the Daraa region. The escalation culminated in direct strikes on high-profile sites, including the General Staff building, the Ministry of Defense and again the vicinity of the presidential palace. Israeli Defense Minister Israel Katz declared that “Israel has ended the phase of warnings,” threatening what he termed “painful strikes” against Syrian regime assets should Damascus fail to meet Israeli demands.[19]

Even amid these hard-power tactics, Israel maintained its soft power posture by announcing the allocation of 2 million shekels in aid to the Druze community in Suwayda. The assistance included food parcels, medical supplies, first aid kits and essential medicines.[20]

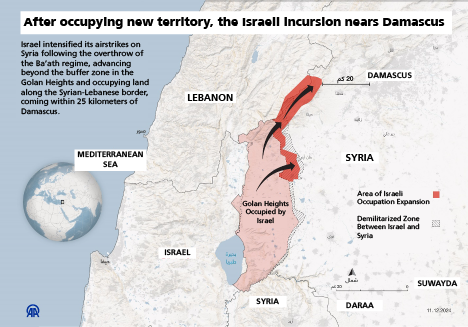

Figure 1: Israeli Expansion in Syria After the Fall of the Syrian Regime

Source: Anadolu Agency – https://www.aa.com.tr/ar/info/%C4%B0nfografik/42665

Objectives and Tools in the Indirect Security Sphere

The partial Israeli security arrangements mentioned earlier fit into a broader vision of Syria as a neighboring state — one defined by its various geopolitical strengths, its role in regional and global dynamics and its potential impact on Israeli national security. Within this framework, Israel’s main objectives and concerns regarding Syria are:

A Fragile State on the Verge of Failure

Israel harbors dual concerns regarding Syria’s trajectory: it fears both the rise of a powerful Syrian state and the collapse of the Syrian state. As such, Israeli strategy seeks to confine Syria to a space of prolonged weakness — closer to dysfunction than strength. While complete state failure and ensuing chaos are also viewed as dangerous, given the absence of a central authority to contain militant threats, Israel considers a resurgent, militarily capable Syria an even greater risk.

Although the new Syrian government has declared its intent not to threaten any neighboring state, including Israel, Israeli security circles remain skeptical. From their perspective, Syria continues to represent a medium and long-term threat, especially after its miscalculation in falling for Hamas’ strategic deception prior to the events of October 2023. Consequently, Israeli policy is likely to focus on ensuring Syria remains without the military capacity to challenge Israel’s security equilibrium.

Strategically Backing the Autonomy of Minority Communities

Israel views Syria’s ethnic and sectarian diversity as a strategic lever to weaken the central state. One of its core tools is the minority card — empowering peripheral communities with various levels of autonomy to dilute Sunni majority dominance. Beyond its support for the Druze, Netanyahu declared in March 2025 a policy shift toward building influence through direct alliances with Syria’s minority groups.[21]

Accordingly, Israel is expected to pursue a two-track strategy: coordinating directly with minority factions or pressuring its regional allies to block reconciliation efforts between the Syrian government and groups such as the Kurds and Druze. This approach may also involve backing separatist movements and armed factions, not necessarily to fracture the country, but to undermine its cohesion and destabilize any efforts toward national recovery.

Dismantling Syria’s Military Arsenal and Curbing Its Armament Programs

Israel sees the rearmament of a post-Assad Syrian regime as a direct threat — especially if the new government, recognized as a sovereign actor, leverages alliances and resources to acquire advanced weaponry. To preempt such a scenario, Israel launched multiple airstrikes following the Assad regime’s collapse, targeting large portions of Syria’s military infrastructure, including missile stockpiles and airbases.

This approach has continued, with regular Israeli strikes aimed at undermining Syria’s military revival — most notably against sites such as the T4 airbase.[22] Looking ahead, Israel is expected to combine political pressure, including sanctions and diplomatic conditions, with military force to block any serious effort to rebuild Syria’s arsenal. The late May 2025 air raids on arms depots in Latakia — shortly after US President Donald Trump’s meeting with Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa — highlight Israel’s commitment to keeping Damascus militarily weak, regardless of international political shifts.

Preventing Syria From Becoming a Base for Attacks

Iran-backed militias are unlikely to resume significant operations inside Syria, let alone engage Israel directly. Deep-seated animosity between these groups and both Syrian society and the state has effectively sidelined their role in the country. This dynamic is rooted in Syria’s internal context, not in Israeli actions. By contrast, southern Lebanon remains a far more favorable environment for such militias to operate.

As for Palestinian factions, their presence in Syria remains more complex. While the Syrian government has expressed varying degrees of reservation toward some of these groups, political and social realities — such as the continued existence of Palestinian refugee camps, enduring support for resistance narratives and widespread public sympathy for the Palestinian cause — allow some level of unofficial or even semi-official activity. Support may come in the form of funding or political backing, either openly or discreetly tolerated by authorities.

Israel, however, is expected to actively target this activity. Whether through covert operations or direct military strikes, Israeli efforts will likely focus on disrupting any resurgence of Palestinian factional activity in Syria — especially when such efforts are buoyed by grassroots or government-linked support.

Challenges Facing Israel in Syria

Israel continues to face a range of obstacles that hinder its ability to fully realize its strategic security objectives. These challenges differ across various security domains, particularly when viewed through a medium to long-term lens.

Challenges Within the Sovereign Security Domain

Despite Israel’s full control over this area — granting it extensive capabilities to preserve security and maintain internal stability — it is not immune to certain persistent challenges — including:

Druze Protests and Episodes of Unrest in Syria

The sectarian ties between the Druze communities in Syria and Israel create a dynamic of mutual influence and impact. As a result, civil unrest in Syria can spill over into Israeli society in various ways. This became evident during the clashes in Suwayda in July 2025, when dozens of Druze individuals crossed from Israel into Syria. The Israeli military accused some of its Druze citizens of using violence against its soldiers, stressing that “any act of violence against the security forces is taken very seriously” and that infiltrating Syrian territory constitutes a grave criminal offense subject to legal action. Israeli media outlets criticized the army for its apparent failure to deter these infiltrators.[23] Demonstrations erupted in protest, condemning the army’s inaction in protecting their Syrian “brothers” after tribal factions rejected a ceasefire declared by the Syrian government on the morning of Saturday, July 19, 2025. While Israeli authorities possess strong capabilities to manage such incidents, the potential for their recurrence remains.

Security Threats Moving Into Israel via the Druze

Israel has made several attempts to win over the Druze community in Syria, including offering work permits that would allow Syrian Druze to take up jobs inside Israel. In a public statement about supporting and protecting the Druze, Katz announced a plan to bring dozens of Syrian Druze workers into Israel’s agricultural and construction sectors. However, the Israeli government quickly reversed course — likely due to security concerns. Officials feared that hostile actors could exploit these permits to infiltrate Israel and carry out retaliatory attacks, particularly in light of emerging resistance activities against the Israeli presence in parts of the Daraa countryside.[24] This comes amid an already tense relationship between the Druze in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights and Israeli authorities — a friction rooted in longstanding discriminatory policies and preferential treatment of settlers. While unlikely, there remains a remote possibility that increased interaction between Druze on both sides of the border could eventually give rise to organized groups within the community that actively oppose the occupation, especially if broader regional dynamics make such a move feasible.[25]

Challenges in the Direct Security Domain

These challenges include the following:

The Emergence of Resistance in the Border Zone of Daraa

Daraa Governorate, predominantly Sunni, sits geographically between the Druze-majority regions of Quneitra and Suwayda. During Israel’s incursions into southern Syria, it faced minimal resistance — except from local armed groups in Daraa, which mounted opposition in early April 2025. One such group, the Ahmed al-Deif Brigades, claimed responsibility for launching two rockets at the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights on June 4, 2025. Similar confrontations could recur — and possibly escalate — if Israel seeks to deepen its presence in the area, whether to back the Druze, assert control, or pursue a deal with the Syrian government. Daraa’s demographic makeup makes it a potential stronghold for anti-Israel resistance. This risk may grow if the Syrian government fails to reassert its monopoly over armed force — a failure that could be worsened by Israeli actions. In such a scenario, Israel could unintentionally position itself as a protective force for anti-regime groups in Daraa, against the backdrop of Druze armed factions controlling neighboring Quneitra and Suwayda.

The Prospect of Intra-Druze Violence

Suwayda and other Druze-majority areas in southern Syria are home to a diverse array of religious figures, political currents and militias — each with varying views on the legacy of the Assad regime,[26] the current Syrian government and Israeli involvement.[27] Despite their differences, these groups have largely managed their disputes peacefully. But tensions with Damascus have recently escalated beyond political disagreement. In May 2025, an armed group stormed the Suwayda governor’s office and briefly detained him—an incident widely condemned by Druze activists. Should such confrontations intensify or become more frequent, they risk sparking internal armed conflict within the Druze community. This would run counter to Israeli interests, as such instability could be exploited by rival factions to launch attacks on Israeli targets — particularly if Israel is seen as a catalyst for intra-Druze violence.

Challenges in the Indirect Security Sphere

At the national level in Syria, Israel faces several key obstacles that could derail its strategic ambitions. These central challenges — rooted in political, security and social dynamics — pose significant risks to Israel’s long-term expansionist agenda which involves amassing influence and seizing territory beyond the southern Syrian frontier. The primary challenges are as follows:

International Recognition of the New Syrian Government

In recent months, the Syrian government has made a series of rapid and significant gains as a result of Saudi and Qatari support. Foremost among these was President Trump’s decision to ease sanctions on Syria — reportedly at Saudi Arabia’s request — during his Gulf tour in mid-May. This was soon followed by a similar move from the EU on May 20, and then by Washington’s removal of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham from its list of terrorist organizations on July 7.

These shifts in international policy challenge Israel’s traditional reliance on Western leverage to secure Arab and regional concessions that align with its interests. Historically, Israel has counted on US and European pressure to shape Arab states’ behavior in ways that accommodate Israeli demands, including in their dealings with Damascus. While the West’s conditions for lifting sanctions — such as respect for minority rights, improved human rights and counterterrorism commitments—remain in place, Israel has worked, overtly or behind the scenes, to ensure that its strategic priorities are also part of the equation. The inclusion of the Syrian file in Netanyahu’s talks with Trump, along with discussions on potential normalization, clearly reflects how intertwined these issues have become. From Israel’s perspective, continued Syrian progress without normalization is problematic. It risks reducing the dynamic to a bilateral matter, depriving Israel of international backing. In this context, the connection between internal and external factors is crucial. International achievements like sanction relief boost the transitional government’s domestic legitimacy and weaken the leverage of opposition groups who depend on foreign support. Likewise, any internal successes — particularly on the security front — enhance the government’s credibility abroad, opening the door to further diplomatic engagement and reintegration into the global economy. None of this serves Israeli interests. Israel has long benefited from Syria’s instability, which has kept Damascus diplomatically isolated and militarily weakened. A stable, internationally recognized Syrian government threatens to upend that status quo.

Instability in Syria

Israel’s current approach to Syria risks triggering the collapse of the newly formed regime and plunging the country back into civil war — a perilous scenario that would be hard to contain. Such a breakdown would demand massive financial and human investments from the Israeli military. It could also create fertile ground for hostile forces like Hamas, various Syrian factions, or even al-Qaeda to regroup and launch operations against Israeli interests.

Ironically, a weakened central government in Damascus could benefit Iran. Tehran would likely seize the opportunity to reassert influence through loyalist figures and remnants of its old proxy networks, creating direct competition with Israel for sway over key communities.[28] That is why a total collapse of the Syrian state presents a challenge just as serious as the one posed by its potential recovery. Israel is compelled to walk a tightrope: allowing the Syrian regime just enough capacity to manage the current situation and ensure its own survival, while keeping it constantly distracted and worn down by internal crises. This strategy aims to prevent Syria from regaining full strength without pushing it into total chaos — an outcome that would backfire on Israeli interests.

Regional Powers Backing the Syrian Government

From the moment Bashar al-Assad was ousted, regional powers — particularly Saudi Arabia and Türkiye — were quick to embrace Syria’s transitional government. Alongside Qatar, they have been actively supporting the new regime, with notable success. Their efforts have helped the interim government gain gradual international recognition and have contributed to the easing of sanctions on Syria. Substantial financial assistance is also being provided to speed up the country’s economic recovery. At the Syrian-Saudi Investment Forum 2025, held on July 24, Saudi Investment Minister Khalid al-Falih announced the signing of 47 agreements worth 24 billion riyals ($6.4 billion). He also revealed that over 500 Saudi companies had expressed interest in exploring investment opportunities in Syria.[29]

Türkiye, meanwhile, is playing a more assertive role in the security and military spheres, particularly regarding the Kurdish issue — a shared concern for both Ankara and the new Syrian leadership. Just one day before the Saudi investment announcements, Türkiye revealed that the Syrian administration, led by Sharaa, had officially requested Turkish assistance to bolster its defense capabilities and intensify its fight against terrorist groups, particularly ISIS. The administration also urged the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to implement a prior agreement with Damascus that would integrate them into the Syrian national army.[30] These regional roles, however, directly conflict with Israeli strategic interests. As a result, Tel Aviv is working to counter these efforts through diplomatic maneuvers and by supporting certain minority groups within Syria, as previously outlined.

The Shift in Washington’s Middle Eastern Policy Under Trump

Trump has pursued foreign policy directions that diverge in several approaches — and at times in objectives — from the traditional positions of US institutions. He has even clashed with these institutions, attempting to sideline them to avoid obstacles to his vision. The US intervention in the June 2025 war between Iran and Israel underscored the limited nature of their disagreements, prompting speculation that these differences may be part of a broader strategy of deception.

While debates persist over the extent of strategic divergence between American and Israeli interests — particularly under a far-right government in Tel Aviv — Israel’s current approach runs counter to a core principle historically shared by both countries: the importance of bolstering central governments in fragile Arab states to counter non-state actors. Such groups, especially Hezbollah in Lebanon and pro-Iran Shiite militias in Iraq, offer Tehran avenues for expanding its influence.[31] As a result, it is plausible that Washington could block Israel from continuing certain policies in Syria — or even compel it to adopt a different course — just as Trump once urged Netanyahu to resolve tensions with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Fears of Another Incursion at Par With October 7

Hamas and the new Syrian government share a key feature: both, in different ways, represent transitional cases moving from non-state actors to state-like entities. Hamas has held power in the Gaza Strip since its 2006 electoral victory. This shift played a central role in the strategic deception it used ahead of Operation Al Aqsa Flood. Through a series of calculated decisions, Hamas gave Israeli intelligence the impression that the responsibilities of governance had pushed it to prioritize administration over armed resistance — mirroring the path of the Palestinian Authority. This assumption led Israeli analysts to dismiss the likelihood of an attack.

Under Israel’s deterrence doctrine at the time, Hamas was expected to learn from Hezbollah’s 2006 miscalculation, when its abduction of two Israeli soldiers triggered a 34-day war that devastated southern Lebanon. That experience was supposed to deter Hamas from similar action. In turn, Israel hoped that its brutal response in Gaza would serve as a warning to the new regime in Damascus.

But the October 2023 assault shattered that logic. The attack exposed Israel’s overreliance on a narrow, outdated understanding of its adversaries — especially Hamas. This failure prompted a major reassessment of Israeli security doctrine. Current evaluations suggest that classical deterrence no longer works against jihadist-driven non-state actors. In its place, voices are increasingly calling for a new approach: “decisiveness,” or the complete elimination of the enemy. This marks a shift from relative deterrence to a zero-sum equation — either them or us.[32]

In light of this, the fear of another October 2023-style attack is likely to remain embedded in Israel’s strategic thinking. No matter what steps the new Syrian government takes, Israel may continue to view them as part of a long-term strategic deception — similar to what it believes Hamas executed — until Syria has built up enough strength to strike. Several possibilities arise here. On one hand, Israeli preemptive strikes could succeed in deterring the Syrian regime, especially given that Syria is emerging from nearly 14 years of devastating war, during which much of its population endured suffering on a scale comparable to, or even worse than, what has occurred in Gaza. On the other hand, the regime’s ideological orientation could just as easily push it toward confrontation — mirroring Hamas’ path.

Instigating a Prolonged War on the Syrian Front

Syria today combines the strategic advantages of both Hezbollah and Hamas — while avoiding many of their weaknesses. Like Hezbollah, Syria enjoys strategic defensive depth across its national territory, particularly in Sunni-majority regions. This allows it to set up defensive lines, absorb Israeli strikes, regroup and launch counteroffensives. And like Hamas, the new Syrian authority embraces an independent jihadist ideology — unlike Hezbollah, which operates under the authority of Iran’s supreme leader. These two features make any potential military clash between the still-militia-like Syrian army and Israel likely to turn into a protracted war. A quick resolution would be difficult, especially if the conflict devolves into irregular warfare involving tribal and semi-state armed groups. If Israel crosses certain red lines — such as assassinating the political or military leadership of Syria’s new ruling authority — it risks triggering another grinding war of attrition. It is important to note that sheer military superiority may not determine the outcome. The demographic and geographical balance tilts in Syria’s favor, and Israeli air dominance alone may prove insufficient without ground operations. The other side could deploy tactics to neutralize air power, as seen in Suwayda, where tribal fighters burned tires en masse and fought at night to evade Israeli airstrikes.

Normalization Agreement Concessions

What worries Israel the most is not an all-out war, but rather asymmetric attacks by small groups targeting Israeli settlements in the Golan Heights. This concern makes Israel reluctant to give up the territory it seized after the fall of the Assad regime, especially given its ongoing territorial ambitions. The shock of October 2023 has only reinforced Israel’s push for forward defense lines; its military doctrine has since shifted toward preemptive action and the creation of buffer zones inside enemy territory.[33] On the Syrian side, any move toward normalization or a security agreement includes demands to return to the terms of the 1974 disengagement agreement — terms that run counter to Israel’s updated security doctrine following the 2023 attacks. As a result, any Israeli concession would pose a serious challenge, potentially leaving the relationship without a binding legal framework. This would reduce Israel’s diplomatic flexibility while bolstering the Syrian government’s hand.

Future Scenarios

It is difficult to assess the extent of success or failure of the Israeli strategy due to the expansionist nature of the occupation and the shifts in Israel’s defensive doctrine, largely based on preemptive strikes. Nevertheless, the future scenarios of the Israeli strategy in Syria range between complete success, complete failure or partial success — where Israel achieves its goals in some files and fails in others. From a holistic perspective, the following three scenarios can be noted:

Scenario One: Success of the Strategy

Reaching a comprehensive normalization agreement is the most prominent feature of this scenario, where the new authority in Syria submits to Israeli conditions and agrees to sign a new agreement under which it relinquishes the Golan Heights in favor of Israeli sovereignty, in exchange for promises of settlements in areas occupied by the Israeli army on the eve of the fall of the Assad regime. The most notable indicators of this scenario are the negotiation rounds between the two parties and the direct meetings between officials from both countries, most notably the meeting between Syrian Foreign Minister Asaad al-Shaibani and Israeli Strategic Affairs Minister Ron Dermer in Paris. The likelihood of this scenario lies in the weakness of the transitional government in Syria and the various problems it suffers from across different sectors, especially security unrest in areas populated by minorities and the declared and practical Israeli role in many of them. Thus, the authority in Damascus may find itself compelled to make very large concessions in exchange for its survival. On the other hand, this scenario faces major challenges, the most important of which is that the Israeli demands — starting with the Golan Heights and ending with a form of governance that grants minorities privileges and a special status — are impossible for the Syrian government to accept, as they would lead to a loss of legitimacy and could result in rebellion or a coup from within the structure of the new Syrian authority. Moreover, the new regime has some internal and external cards that grant it room for maneuver without reaching this surrender stage. Based on all this, the likelihood of this scenario is low.

Scenario Two: Failure of the Strategy

The Syrian authority may gradually succeed in dismantling and neutralizing hotspots of tension, and forming regional and international alliances that weaken separatist and armed opposition forces in minority areas, thereby disabling Israeli tools inside Syria. It may also reach a defense agreement with Türkiye that limits Israeli military incursions into Syria. In this context, it is not unlikely that Damascus would allow military activities against Israel to force it to stop its aggression. However, the Israeli side also possesses cards it can play if it notices a comprehensive shift in favor of the new Syrian regime. In this case, a swift war targeting most of the current leadership — similar to what happened with Hezbollah in Lebanon and what was attempted with the Iranian establishment — is not out of the question. Considering the indicators of the previous scenario that overlap with this one, the likelihood of the failure of Israel’s strategy versus the success of the Syrian strategy is also low due to the significant power imbalance.

Scenario Three: Partial Success of the Strategy

The absence of direct security threats from Syria toward Israel — whether directly through the Golan Heights or indirectly as a corridor to Lebanon and then Israel — is considered a strategic gain, but remains insufficient, especially after the October 2023 operations. The Israeli occupation achieved additional gains following the fall of the Assad regime by expanding into new areas. On the other hand, there are currently no security threats that pose a military burden forcing Israel to enter into an agreement that does not preserve these gains, including a return to the previous status quo. Israel is also progressing in achieving its other objectives inside Syria, having secured some gains in the military confrontation that took place in Suwayda in July 2025. However, these achievements are considered superficial unless crowned by an agreement with the Syrian government that formalizes them. Therefore, they remain de facto accomplishments that secure Israeli interests while Tel Aviv continues to exert more pressure to achieve other goals whenever circumstances and developments allow. This is the most likely scenario, where relations will continue to oscillate between negotiations, pressure and incremental gains, while Syrian maneuvers aim to buy time and neutralize as many internal threats as possible.

Conclusion

On the eve of the Assad regime’s collapse, the Israeli government took several military and political steps that expanded its strategic advantage — compensating for its setbacks in Gaza with gains on the Lebanon and Iran fronts. It secured new strategic terrain, enhancing its early-warning capabilities and boosting its military superiority as part of its deterrence strategy. Yet these gains remain short-term. To lock in long-term advantages, Israel devised a multilayered set of objectives toward Syria, blending hard and soft power tools across its security perimeters. Syria’s internal disarray — the central government’s fragility, a battered economy inherited from decades of Ba’athist rule and civil war, and the presence of militia forces with both military ambition and local support in minority strongholds — offers Israel a variety of openings and opportunities to achieve its goals in the country. Still, Israel faces key challenges — chief among these, Syria’s potential resurgence. Over time, Syria could reemerge as a regional power, which Israel views as a threat to contain early. Meanwhile, Israel’s power surplus comes with risks: deeper military involvement in Syria could spiral into unintended confrontations, violating Syrian sovereignty and inflaming social tensions. These complications underscore the difficulty of reaching a viable settlement and suggest that relations between the two countries are likely to hover at low-grade escalations — or even slide toward open war.

[1] For further details on the Israeli strategy toward the Syrian crisis during that period, see: Yahya Bouzidi, “The Iranian-Israeli Confrontation in Syria: Between the Limits of Security and the Limits of Influence,” Turkish Vision 8, no. 2, Spring 2019, 83-101. [Arabic].

[2] Rob Geist Pinfold, “Why Is Israel Escalating Its Strikes Against Syria?” The Royal United Services Institute, May 9, 2025, accessed July 24, 2025,https://2u.pw/ZzR3Z.

[3] Helmi Moussa, “Israel Makes a Radical Change to Its Combat Doctrine… What Did It Do?” Al Jazeera Net, January 13, 2025, accessed May 26, 2025, https://2u.pw/gfNsM. [Arabic].

[4] “Israeli Army Establishes Rapid Intervention Unit on Border With Syria,” Asharq Al-Awsat, December 04, 2024, accessed July 24, 2025, https://2u.pw/NrFGjdiV. [Arabic].

[5] “Israeli Army Establishes Rapid Intervention Unit on Border With Syria,” Asharq Al-Awsat, December 04, 2024, accessed July 24, 2025, https://2u.pw/NrFGjdiV. [Arabic].

[6] “Israeli Channel: Land Barrier Soon on Border With Syria,” Al Jazeera.net, October 14, 2024, accessed July 24, 2025, https://2u.pw/ZEdMt. [Arabic].

[7] Zohar Palti, “Syria Is the First Major Aftershock Following October 7 — Is More to Come?” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, December 11, 2024, accessed May 15, 2025, https://2u.pw/Cf2qH. [Arabic].

[8] “Israeli Escalation in Syria in Early 2025: Strikes, Targets, and Implications,” Harmoon Center for Contemporary Studies, February 18, 2025, accessed May 19, 2025, https://2u.pw/6A5eR. [Arabic].

[9] “Exclusive: Israeli Army Penetrates Deep into Syrian Territory amid Syrian Silence,” I24 News, October 14, 2024, accessed July 28, 2025, https://2u.pw/zramK. [Arabic].

[10] Shira Efron and Danny Citrinowicz, “Israel’s Dangerous Overreach in Syria,” Independent Arabia, April 27, 2025, accessed May 12, 2025, https://2u.pw/P4HaX. [Arabic].

[11] Sawsan Mhanna, “Mount Hermon… Now an ‘Israeli Eye,’” Independent Arabia, December 23, 2024, accessed May 28, 2025, https://2u.pw/zZB2m. [Arabic].

[12] Ibid.

[13] “Israel Seeks to Maintain Zones of ‘Control’ and ‘Influence’ Deep Inside Syria,” Asharq Al-Awsat, January 10, 2025, accessed July 24, 2025, https://2u.pw/SUcLztn0. [Arabic].

[14] Yedioth Ahronoth, “How Israel Has Doubled Its Military Presence Inside Syria,” Al Jazeera Net, May 06, 2025, accessed May 12, 2025, https://2u.pw/AkWrn. [Arabic].

[15] Efron and Citrinowicz, “Israel’s Dangerous Overreach in Syria.”

[16] In March, Israel allowed 100 Syrian Druze to visit its territory. The following month, Israeli Defense Minister Israel Katz approved the entry of 600 Druze clerics to attend the annual Nabi Shuʿayb festival, which includes visiting the shrine near Hittin between April 25 and 28 April each year. See: “With Katz’s Approval: 600 Druze Clerics from Syria to Visit Nabi Shuʿayb Shrine on Friday,” Arab 48, April 24, 2025, accessed July 21, 2025, https://2u.pw/FfJ2I. [Arabic].

[17] For instance, an Israeli Air Force helicopter delivered humanitarian aid to Syrian Druze in the Suwayda area, around 70 kilometers from the Israeli border. The aid came as the Israeli army evacuated five other injured Syrian Druze — apparently hurt in sectarian violence — to Ziv Hospital in Safed. At least 10 more wounded Syrian Druze were transferred in recent days. See: “Israeli Helicopter Delivers Aid to Druze in Southern Syria 70km From Border,” Times of Israel, May 04, 2025, accessed May 28, 2025, https://2u.pw/5C8sR.

[18] “From Sectarian Tension to Israeli Intervention: A Reading of the Events in Jaramana, Ashrafiyat Sahnaya, and Suwayda,” Harmoon Center for Contemporary Studies, May 10, 2025, accessed May 20, 2025, https://2u.pw/nwxLX. [Arabic].

[19] “Israel Bombs Central Damascus as Katz Speaks of ‘Painful’ Strikes,” Times of Israel, July16, 2025, accessed July21, 2025, https://2u.pw/uyr9t. [Arabic].

[20] “Syria: Israel Sends Aid to Druze in Suwayda – Here’s What It Includes,” CNN Arabic, July 18, 2025, accessed July21, 2025, https://2u.pw/Qi0wS. [Arabic].

[21] Efron and Citrinowicz, “Israel’s Dangerous Overreach in Syria.”

[22] The T4 Airbase, also known as Tiyas or Tyas, is located near the village of Tiyas in Homs Governorate, approximately 60 kilometers east of the ancient city of Palmyra. It lies in a strategic desert region that contains Syria’s main gas fields. T4 is one of the largest military airports in Syria and served as a key hub for Syrian air force operations. For more, see: “T4: A Syrian Military Airport Contested by International and Regional Powers,” Al Jazeera Net, April 6, 2025, accessed August 28, 2025,https://2u.pw/h4So2. [Arabic].

[23] “Israel Attacks al-Sharaa… Accuses Him of ‘Conspiracy Theories,’” Asharq Al-Awsat, July 19, 2025, accessed July 20, 2025, https://2u.pw/gRlb3. [Arabic].

[24] “Security Concerns Push Israel to Cancel Plan to Admit Syrian Druze into the Golan,” Middle East Online, April 02, 2025, accessed June 02, 2025, https://2u.pw/AFRjt. [Arabic].

[25] For more details on the nature of the relationship between the Druze community in the Golan and the Israeli occupation, see: Tayseer Maraybi and Osama R. Halabi, “Life Under Occupation: The Golan Heights,” Journal of Palestine Studies, vol. 4, no. 13 (Winter 1993).

[26] Positions ranged from support for the regime, to neutrality in the conflict, to siding with the revolution — with only very limited confrontations with the regime. For more details on the map of militia presence in Suwayda prior to the fall of the Assad regime, see: Yaman Ziyad, “Armed Groups in Suwayda: The Duality of Security and Drugs,” Omran Center for Strategic Studies, November 11, 2024, accessed July 20, 2025, https://2u.pw/PwQ9C. [Arabic].

[27] After the fall of the Assad regime, conflicts surfaced in various forms, including local factions’ rejection of the military council established by Tarek al-Shufi, head of the Federal Syria Movement, which advocates federalism for Suwayda — especially given the presence of regime army officers within the council. Factions within the military council also blocked the entry of internal security vehicles formed under an agreement between the Joint Operations Room in the province and the Damascus government. This coincided with demonstrations organized by the Federal Syria Movement calling for the fall of the current regime and praising both Sheikh Hikmat al-Hijri and Sheikh Mowafaq Tarif. Armed clashes occurred among these groups, most notably the Men of Dignity movement’s campaign against the militias of Raji Falhout — formerly the largest militia in Suwayda — which resulted in its complete dismantlement. For further details, see: Yaman Zabad, “Suwayda After Assad’s Fall: A Study of Shifting Military Forces and Political Demands,” Harmoon Center for Contemporary Studies, 03/13/2025, accessed May 21, 2025, https://2u.pw/GqrBL.

[28] Nir Boms, Carmit Valensi and Mzahem Alsaloum, “Beyond the Brink: Israel’s Strategic Opportunity in Syria,” The Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), Insight No. 1979, May 8, 2025, accessed July 24, 2025,https://www.inss.org.il/publication/new-syria/.

[29] “Saudi Investment Minister: 47 Agreements Signed to Inject $6.4 Billion Into Syria,” Al-Sharq Website, July 24, 2025, accessed July 27, 2025, https://2u.pw/3HKxx. [Arabic].

[30] Ibid.

[31] Boms, Valensi and Alsaloum, “Beyond the Brink: Israel’s Strategic Opportunity in Syria.”

[32] This perspective assumes the possibility of conflict management through rational deterrent mechanisms based on the principle of reward and punishment, as if Hamas adopts the same political logic embraced by the modern liberal state: a calculative logic that balances gain and loss, deterrence and punishment, costs and benefits. From this point, the epistemological foundation upon which deterrence was built began to erode, prompting calls for its reassessment. For more, see: Walid Habbas, “On the Philosophical Foundations of the Concept of (Failed) Deterrence in Israeli Security Doctrine,” Madar – The Palestinian Center for Israeli Studies, March 24, 2025, accessed July 10, 2025, https://2u.pw/X9cVL. [Arabic].

[33] Efron and Citrinowicz, “Israel’s Dangerous Overreach in Syria.”