Abdulraouf Mustafa al-Ghunaimi

A researcher at the International Institute for Iranian Studies (Rasanah)

Ahmed Shamsadin Leila

A researcher at the International Institute for Iranian Studies (Rasanah)

Iran-China relations has developed into a partnership and understanding. In international relations this represents an advanced and strong level of coordination and consultation. The extent of Iran-China relations became apparent when China officially rejected the US maximum pressure strategy to change Iran’s behavior. This included Beijing’s initial rejection of the US withdrawal from the nuclear agreement, and the reimposition of US economic sanctions on Iran. In addition, Beijing refused to lower its imports of Iranian oil to zero in spite of the severe US sanctions against Iran.

Undoubtedly, these developments pave the way for deeper cooperation between China and Iran and may reach the level of international integration. This situation can occur when the views of two countries converge over regional and international affairs. The Chinese-Iranian relations is expected to face an important reality check impacting the future course of bilateral relations due to two main reasons: the Iranian developments along with rising tensions with international powers, principally the United States; the ongoing debate over China’s position in relation to the vote in the next battle between Washington and Tehran in the Security Council in October 2020 to extend the arms embargo on Iran.

Accordingly, this study will focus on the determinants impacting Iran-China relations, review the issue of cooperation and divergence to interpret the nature of relations between the two countries as well as China’s historical position on US encirclement policies toward Iran. In addition, this study will predict China’s position in regard to the vote to extend the arms embargo which would shift Iran’s power level if not extended. This could exacerbate the level of the conflict in the Middle East.

I. Explanatory Determinants of the Strategic Partnership Between Iran and China

China is a reliable partner of Iran and vice versa in opposition to US encirclement policies. This is due to several determinants as follows:

1-The Absence of Negative Remnants in the Course of Relations

Returning to the deeply rooted Chinese-Iranian relationship, we find that trade has dominated relations between the two countries ever since its onset during Persia’s imperial rule. The ancient Persian empire entered into a commercial partnership with China through the land routes of the Silk Road. These routes were used by Chinese trade convoys to travel from China to Persia and to Western Europe.

In modern times, Chinese-Iranian relations were economically weak during the Shah’s era because Iran prioritized the United States and Europe in its foreign policy. However, relations between the two countries were exclusively political. Since China recognized the nationalization of Iran’s oil industry in the 1950s, Tehran in return recognized the People’s Republic of China in 1967 and supported the People’s Republic of China in gaining membership to the Security Council in 1971 in place of the Republic of China led by Chiang Kai-shek who was backed by the United States. In 1978, former Chinese President Hua Guofeng made his last foreign visit to the Shah before the fall of his government.[1]

Post-revolution 1979, relations warmed because of the change in the Iranian political system and because the clergy tightened their grip on power. This shifted Iran’s foreign policy away from America and Europe. Since then, hostilities have emerged between Iran and the United States and its strategic and traditional allies in the region. Beijing quickly recognized Iran’s revolution. It joined the list of countries supplying arms to Iran during the Iran-Iraq war. This was a very critical time for Iran after an arms embargo was imposed on it because of the 1979 hostage crisis.[2] Iran did not forget China’s support, as a result Beijing earned the trust of Iranian clerics despite their reservations over China’s good relations with the Shah.

By the 1990s, a new phase between China and Iran took shape as bilateral relations entered the stage of “strategic cooperation” due to similar shifts in both countries. Khamenei became the Supreme Leader after Khamenei’s demise in 1989, likewise Jiāng Zémín came to power in 1992. In addition, China moved from exporting oil to importing oil in 1993 against the backdrop of rapid economic development thanks to the vision of the reformist engineer Deng Xiaoping. Iranian oil was imported by China.

At the beginning of the 1990s, international transformations played a critical role in strengthening relations between Iran and China extending to the economic, commercial and military spheres as well as the political sphere. Both countries realized that Washington was adopting a policy of encirclement and embargo towards them, at a time when China’s need for oil was growing due to growing local production. The growing Chinese military cooperation with Iran stimulated the US-China conflict in the Taiwan Straits in 1996, increasing the chances of confrontation in the straits. Therefore, China reduced its military cooperation with Iran due to its intent to restore calm in the Taiwan Strait.

By the end of the 1990s, their relations returned stronger after Beijing prioritized an open policy in order to access global markets for its products as well as open access to oil. Iran was among the important oil alternatives for China. After Beijing opposed the American reception of Taiwan President Lee Teng-hui in 1997, and the latter rejected China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 1995, which it later joined in 2001,[3] China ignored American demands to lower its levels of cooperation with Iran.

As Washington adopted a policy of sanctions against both countries, Chinese-Iranian relations deepened. China refused to refer Iran’s nuclear file to the Security Council and signed a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Agreement with Iran in 2015. It also raised the level of trade and investment exchange with Iran, and rejected the US withdrawal from the nuclear agreement and the reimposition of sanctions on Iran in 2018.[4] The United States pursues a policy of encirclement towards both the rising Chinese giant in East Asia to maintain its leading position in the international system, and Iran as the regional power in the Middle East to uphold Israel’s qualitative superiority and to ensure the balance of power between regional actors.

By reviewing the history of Iran-China relations, it becomes apparent that their relationship is very solid and clear of any hostilities like conflicts, wars, colonialism, occupation, and annexation. This played a role in building confidence between the two countries and strengthening bilateral relations.

2- The Nature of the Political System in Both Countries

The nature of both political systems in China and Iran has played a significant role in strengthening relations between the two countries. Their political systems can be characterized as oligarchic or dominated by minority rule – in which power is in the hands of a few segments of society – aristocrats, theocrats, the military, a political party – by virtue of the fact that the Chinese government is led by a single dominant party, the Chinese Communist Party, that monopolizes all sources of political power. Similarly, Iran’s political system is led by clerics who monopolize all sources of power.

The Chinese and Iranian political systems share anti-Western values and resist calls for political pluralism and democratization based on the European and American models. Both systems believe that Western values pose a threat to their survival. Therefore, Beijing is not concerned about Tehran posing a threat to the Chinese home front and vice versa. China supports minority rule and does not permit opposition to the existing political system.

3- Mutual Strategic Economic Need

China’s economic importance to Iran stems from three fundamental factors. First, China has had no problem in transferring modern technology and complete production lines to Iran. It has also been providing financial support to Iran’s economic and development projects since the early 1990s. Secondly, China’s industrial policy does not care much about the end-use of its exports unlike many countries in the world, especially European countries. This includes the use of its exported products and goods for industrial and medical purposes or even military purposes. Iran imported MRI machines from China for medical purposes but they were used instead for military purposes such as to check missile malfunctions and to scan military equipment. China, however, overlooked the whole matter. Thirdly, there is an Iranian desire to maintain close and friendly relations with the largest buyers of its oil and petrochemical exports and to find a reliable industrial supplier in times of crisis as an alternative to European manufacturers whose interests overlap strongly with the United States at the expense of Iran.

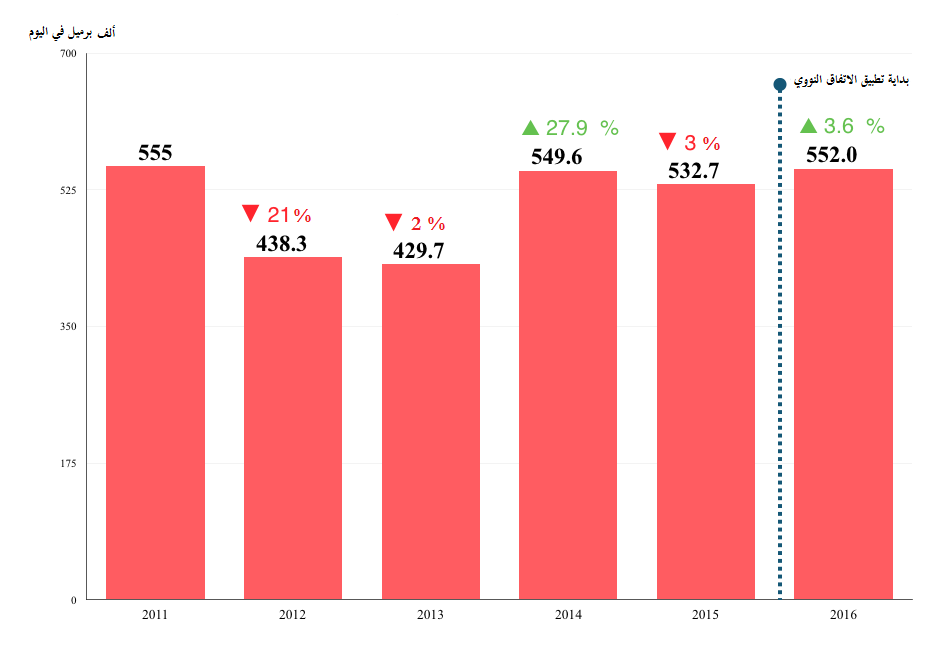

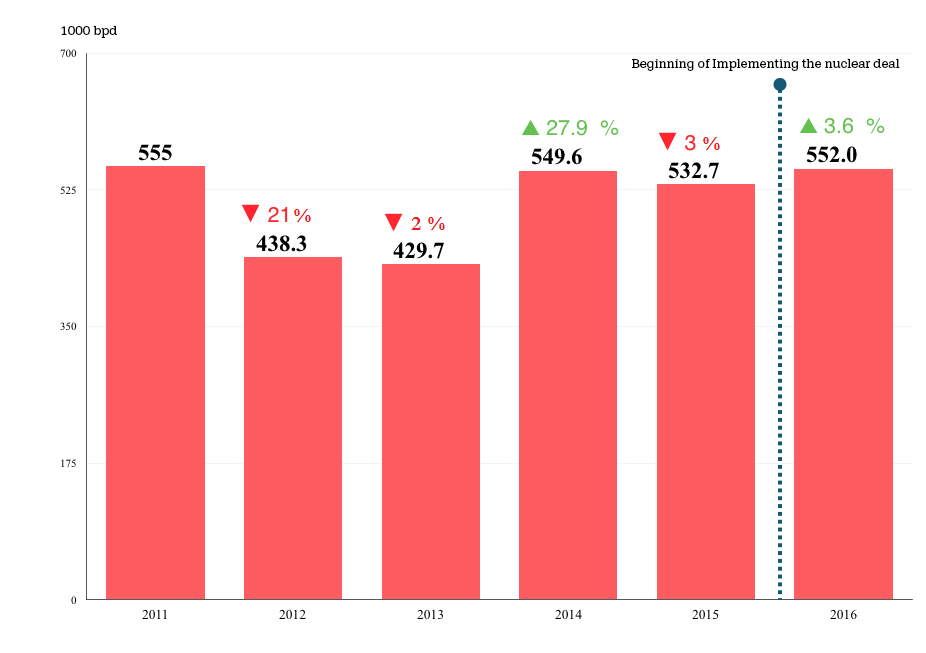

Iran’s economic importance to China stems from three factors. First, Iran is one of the most reliable oil suppliers to China. It possesses huge oil reserves amounting to 1.584 billion barrels, ranking it fourth in the world after Venezuela, Saudi Arabia and Canada with 9.3 percent of global reserves.[5] If the new Iranian field reserves of more than 50 billion barrels announced by Tehran in November 2019 are added, Iran will be ranked third in the world.[6] Particularly, Iran is the second largest supplier of crude oil to the Chinese economy after Saudi Arabia. Part of China’s long-term strategy is to diversify its energy supplies, especially from the Middle East which experiences a great deal of geopolitical volatility impacting the stability of oil supplies. During periods of economic blockade on Iran, China often benefits from Iranian facilitation in transporting oil or in using alternative payment methods. Therefore, Chinese imports of Iranian oil did not decline significantly when sanctions and the international blockade against it intensified in 2012 and 2013. The following graph (Figure 3) shows that imports decreased by about 20 percent during these two years and then returned to their previous levels in 2014 and 2015, two years before the activation of the nuclear agreement. Although China’s imports of Iranian oil fell more than 50 percent after the extension of US exemptions from sanctions ended on Iran in May 2019, in the long run it will compensate for this decline. by increasing imports from Iran in the future

Figure 3: China’s Imports of Iranian Oil (2011-2016)

The second factor is the centrality of Iran’s location as it is situated along the Chinese Silk Road and is the primary corridor to transport Chinese goods to Central Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Europe. In exchange, this corridor is also used to transport raw materials to China. The third factor is that China uses its relations with Iran as a pressure card against the United States to obtain competitive advantage or the upper hand in the disputes that emerge from time to time, such as the dispute between both countries over tariffs or the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, as well as other files that influence China’s position in the global economy.

4 – Geo-political Considerations

Iran’s location is of geopolitical significance to China because it is located in the southwest of Asia and overlooks the most important strategic bodies of water: the Arabian Gulf, the Arabian Sea, the Indian Ocean and the Caspian Sea. Thus, it is a link between East and West and a natural corridor for world trade and an important conduit for China. It is a bridge between Central Asia, East Asia, West Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean. It is bordered on the east by Pakistan and Afghanistan; on the west by Turkmenistan; on the southwest by the Arabian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman; and on the west by Iraq, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Turkey, and the Caspian Sea. Iran is a vital corridor for importing and exporting between the East and West.

Therefore, this strategic location offers China a foothold in the vital Middle East, with all its strategic commodities, natural and mineral resources, as well as broad markets and international shipping lanes through which oil tankers cross over to China. Iran’s location gives China the opportunity to maintain a presence in the region to compete with the United States. It provides an opportunity for the expansion of Chinese strategic geographic influence way beyond its immediate neighborhood in Asia and the Pacific region. Moreover, Iran’s location helps China expand its geostrategic influence beyond its surrounding neighbors in Asia and the Pacific Ocean; therefore, Iran is not a mere oil supplier for China.

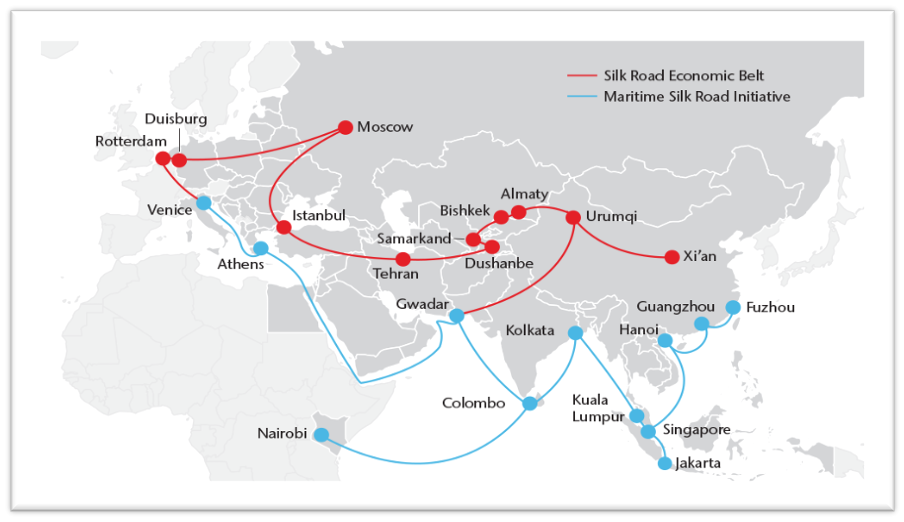

Iran is located within the network of countries that form part of the Chinese project to revive the Silk Road, which was proposed by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013. This giant transcontinental economic project is known as the Belt and Road Initiative. This trade route connects China to Europe and Africa, stretching from Central Asia to India and East Asia, and extending to the Gulf countries toward Africa. There is another road that passes through Iran towards Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and possibly to Israel, as well as a road that runs through Iraq towards the Turkish territories, Cyprus, and Europe.[7]

Map of China’s Belt and Road Initiative

This project is of great importance to Iran because of its positive impact on its economy leading to increasing demand for its oil from countries located along its border. This project provides Iranians the opportunity to achieve the Iranian dream envisioned since the era of the late President Hashemi Rafsanjani in the late 1980s that “Iran is the heart of the Silk Road,” underscoring the international geopolitical importance of Iran’s location. Therefore, during the Chinese president’s visit to Iran in 2016, China and Iran signed an agreement to turn Iran into a “transit center” for Chinese goods once the Silk Road is completed.[8]

China’s position is of strategic importance to Iran because it is located in East Asia with its vast area. China has borders with 21 countries by land and sea. China also controls the Taiwan Strait connecting China’s southern and northern seas where trading ships carrying strategic goods pass through from South Korea and Japan, allies of the United States. Given its geographical location, China possesses international pressure cards which Iran can benefit from.

5- American Encirclement Policies

Firstly, the shift of the international system to a unipolar system in the early 1990s was accompanied by a decline in China’s importance in the United States’ strategy. This led to the end of the American-Chinese alliance that emerged during the Cold War to confront the former Soviet Union. The United States started to consider China as a competitor in the international system. Secondly, the United States gave priority to containing Iran because Tehran adopted a revolutionary foreign policy that threatened important US strategic allies such as Israel and traditional allies such as the Gulf Arab states. Therefore, the United States pursued a policy of “double encirclement” toward the rising Chinese giant in East Asia and revolutionary Iran in the Middle East, as follows:

A. The US encirclement policy towards China: In the time it has been unilaterally leading the international system since the early 1990s, Washington rearranged its cards and identified its allies and opponents. Accordingly, China was identified as a potentially growing threat to its leadership position in the international system. This explains America’s decision to block China’s accession to the World Trade Organization until 2001when Washington realized the importance of China in the fight against terrorism against the backdrop of 9/11.[9] In addition, this explains the signing of a nuclear cooperation agreement between the United States and India to contain the rise of China. This agreement has enabled India to import nuclear technology and to be a thorn in the side of a rising China in the post-Cold War era.

Former US President Barack Obama adopted the policy of “pivoting east” and the policy of encirclement and containment of the ‘Chinese dragon’ to isolate it internationally. This explains his administration’s endeavor to strengthen relations with historical allies such as Japan, South Korea and Thailand, and to establish new partnerships with neighboring countries directly or indirectly to counterbalance the rising Chinese juggernaut such as Brunei, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore.

With Trump coming to power, US encirclement policies against China escalated with the waging of a trade war against Beijing. In July 2018, the Trump administration imposed successive tariffs, reaching about 30 percent in August 2019, on Chinese imports worth $450 billion. In response, Beijing implemented similar retaliatory measures by imposing tariffs on US imports worth $170 billion.[10] Washington accused China of concealing important information and spreading false information about the coronavirus. Trump used the term “China virus” which was offensive to the Chinese government.

The United States’ fear of China is due to its transformation into an international power possessing the capabilities to compete for the leadership of the international system due to the following;

1-China has a veto. Thus, it has an international pressure card against any draft resolution proposed by the Security Council, including draft resolutions against Iran and its proxies in the region.

2-China possesses economic and military capabilities. Its economy is ranked second in the world after the American economy, and China ranks third militarily after the United States and Russia, in relation to power indicators, and military spending, as well as in terms of the number of military personnel, aircraft, and air, land and sea missiles it possesses.[11]

3-China is one of the most important founding members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). According to some international relations experts, the SCO is not merely an organization for for coordination commerce and son on, it is a military alliance. Some observers even believe that it has succeeded the Warsaw Pact. Therefore, the SCO led by a Russian-Chinese regional power pact is a threat to American interests in Central Asia.

4- China established the AIIB and pumped $100 billion into it. It acts as an international financial competitor to end the West’s financial domination via institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.[12]

B. American encirclement policy towards Iran: Washington seeks to encircle Iran and prevent it from becoming a regional leader. The administration of former President George W. Bush described Iran as a state sponsor of terrorism. However, the administration of former President Barack Obama tried to contain and integrate Iran into the international community by signing the 2015 nuclear agreement. The Trump administration announced its withdrawal from the nuclear deal in May 2018 and reinstated economic sanctions against Iran. It signed two packages of sanctions against Iran in August 2018 and November 2018 in relation to the country’s oil sector. Trump’s administration ended the sanction waivers it had provided to eight countries importing Iranian oil in early May 2019. The United States pursued sanctions on several vital Iranian sectors. It designated the IRGC as a terrorist organization, targeted its regional proxies, and assassinated Iran’s Commander of the Quds Force Qassem Soleimani in January 2020.

II.The Level of Relations and the Dimensions of the China-Iran Strategic Partnership

After the Iranian revolution, Chinese-Iranian relations improved. The development of these relations can be viewed through the following:

1. Economic and Commercial Cooperation

China-Iran economic relations during the Shah’s rule were cold and weak. Iran’s trade was directed towards several European countries including Germany, Britain and France, in addition to the United States and Japan. 21 percent of Iran’s imports in 1978 were from Germany, and 15 percent from the United States, compared to less than half a percent from China (0.5 percent). In the same year, 45 percent of Iran’s exports went to the United States. However, Iran’s exports to China did not exceed a significant level of (0.3 percent) Iran’s total exports to the outside world in that year.[13] Table No. 1 shows Iran’s volume of trade with China and the rest of the world between 1981-2018.

A. The development of economic relations since the revolution: Over the past 40 years since the 1979 revolution, Chinese-Iranian relations have gone through four stages. First, the minor Chinese support during the war with Iraq in the 1980s; second, Iran’s increased confidence in China and Iran’s reconstruction after the war from the late 1980s until the mid-1990s; third, the fostering of relations and Chinese development assistance in major projects, in exchange, Iran became one of China’s major energy exporters from 1992 to 2005; and fourth, the stage of trade relations growing from 2006 until now, which has not been free from some challenges impacting the extent of cooperation between the two countries.

1- The first stage (1979-1989): During this period, Iran mobilized all its resources to serve the war effort. China’s imports were limited to the military sector only. Economic relations were in their infancy. China supported Iran with military equipment, the transfer of military technology and ammunition production facilities. Until the end of the 1988 war, Iran did not trust Chinese products. Therefore, Iran’s trade with China was strictly limited to less than 1.5 percent of its total trade with the outside world.

2-The second stage (1989-1991): During this stage, China tried hard to earn the trust of Iranian decision makers and to attracs Iran’s foreign trade towards Chinese industry, over a long period of time. China helped to reconstruct what the war with Iraq destroyed over eight years in Iran, especially road infrastructure, housing and factories for construction materials such as cement, iron, copper and zinc. In addition, China provided much-needed parts for Iran’s oil and petrochemical industries, and helped to construct dams and power and hydroelectric stations. Thus, the trade volume between the two countries doubled and reached nearly $341 million in 1991, although it was still small compared to Iran’s trade with the rest of the world. In addition, the trade balance between the two states was totally in China’s favor.

3- The third stage (1992-2005): Iranian confidence in Chinese technology and commodities increased. China had already helped Iran to establish major development projects and had transferred advanced technology. On the other hand, Iranian exports to China were still limited, whether oil or raw material exports. However, bilateral trade increased compared to the previous stage. China also signed a contract to construct the Tehran Metro in 1992 to cover the entire capital under the condition that China provided 75 percent of the project equipment, the financial support and advanced technology. The first phase of the project was launched in 2000 in the presence of the former Iranian President Mohammad Khatami and Chinese Foreign Minister Tang Jiaxuan.[14]

Moreover, Tehran’s Metro is the largest subway project implemented by Chinese companies outside China. Iranian confidence in Chinese companies operating in Tehran served as a means to advertise and promote modern Chinese technology and industry. China has completed a 295-kilometer railway linking the city of Mashhad in northeastern Iran to the Turkmenistan border. It appears that China had long-term goals since then to access Central Asian markets through Iran.

The Chinese-Iranian partnership expanded beyond infrastructure to include major industrial projects. China set up auto factories and built huge oil tankers for Iran through credit loans from Chinese banks. It also contributed to modernizing Iran’s fishing fleet, maritime transportation, and mineral industries. Iran also imported from China equipment for its oil/gas and petrochemical industries, as well as heavy diesel engines and electric motors. Nearly half of the value of capital goods that Iran imported from China was paid through Iranian oil sales to China.

4-The fourth stage (2006-present): Economic relations between the two countries entered a deeper and more cooperative stage. In this stage, the two countries decided that their economic cooperation should be balanced rather than one party benefiting at the expense of the other. China aims to gain a large share of the Iranian market, especially to export consumer goods. Iran wants to help China in major development projects, particularly in the oil industry, and to increase China’s imports of its oil in order to tip the trade balance to such an extent benefiting both countries, not just China as was the case previously as shown in Table 2.

Table 1: Iran’s Trade With China and the World From 1981-2018 (in Billion Dollars)

| State/Year | 1981 | 1988 | 1998 | 2000 | 2008 | 2011 | 2017 | 2018 |

| China | 0.122 | 0.511 | 1 | 2.3 | 23.5 | 38.5 | 39 | 30.7 |

| With the World | 23.5 | 18.7 | 27.4 | 39.2 | 164.2 | 176 | 116.2 | 117.1 |

| Percentage | 0.5 | 2.7 | 3.6 | 6 | 14 | 22 | 33.5 | 26 |

Source: Researcher’s calculations based on data: IMF, Direction of Trade Statistics

B. Indicators of cooperation and growing economic relations: As shown in Table 2, the volume of bilateral trade has doubled several times since 2005. Iranian oil exports to China have increased significantly, making it one of the largest oil suppliers to China after Saudi Arabia. The volume of bilateral trade increased by more than $10 billion in 2010,[15] including 44 percent of Iranian exports which went to China. The latter has become the largest buyer of Iranian oil and has taken the place of Japan, meaning that Iran has succeeded in reducing the trade deficit between them by increasing its exports to China. On the other hand, China has increased its exports to Iran in various fields including consumer goods, and industrial/electrical products, as well as industrial spare parts which have flooded Iranian markets as they have done with other international markets.

Table 2: Trade Balance Between Iran and China From 1997-2016 (in Billion Dollars)

| Iran | 1997 | 2002 | 2005 | 2010 | 2016 |

| Imports | 0.400 | 0.985 | 2.4 | 5.7 | 10.6 |

| Exports | 0.62 | 0.185 | 0.500 | 4.4 | 8.3 |

Source: UN, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Trade Statistics.

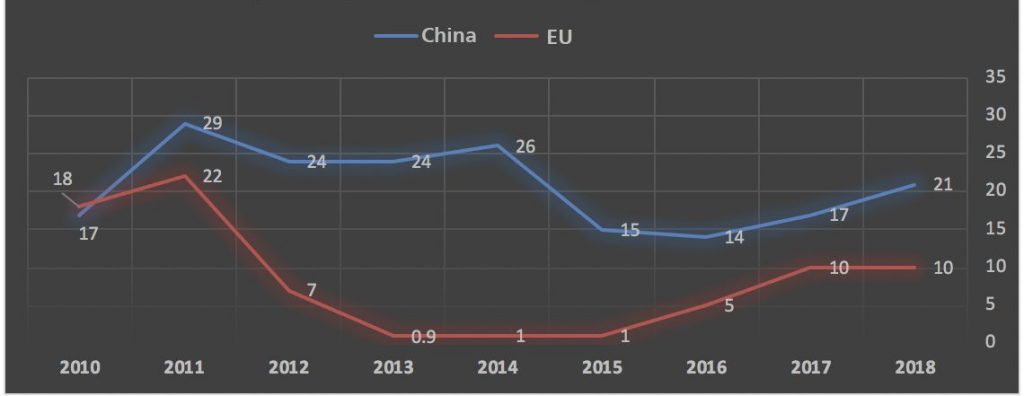

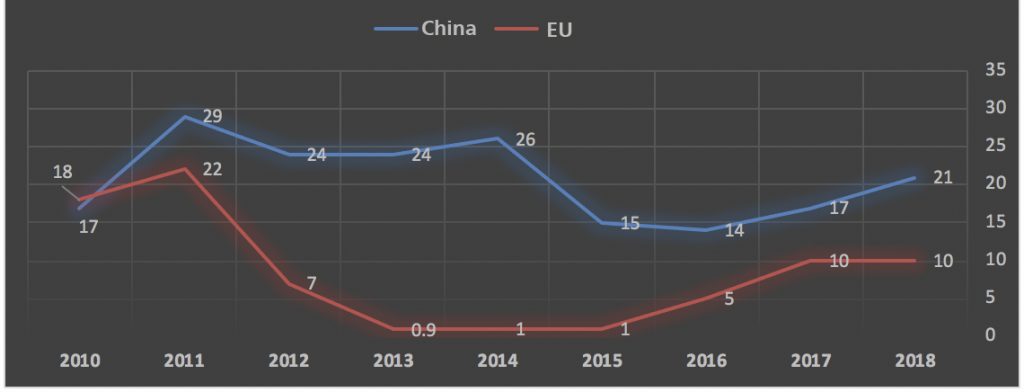

Iran-China economic and trade relations have not declined significantly following the imposition of severe economic sanctions against Iran. On the contrary, they have increased. From 2010 to 2018, various economic sanctions were imposed on Iran by international and European parties on its trade, oil, and banking sectors. In 2011, for the first time, China became Iran’s largest trading partner surpassing the European Union, which was the country’s most important trading partner for decades. Iran’s trade with China alone was more than a quarter of its trade with all other countries of the world that year. Since then, China has been Iran’s largest trading partner followed by the European Union. The volume of Chinese-Iranian trade reached $40 billion in 2011 (the total of exports and imports), as shown in figures 1 and 2. During this period, the UN Security Council and the European Union imposed sanctions against Iran.

Figure 1: Iran’s Exports to Europe and China (2010-2018)

Figure 2: Iranian Imports From Europe and China (2010-2018)

C. The impact of US sanctions on the economic partnership and oil exports: China often benefits from Iranian facilities to transport oil or to make payments in times of economic blockade. Therefore, Chinese imports of Iranian oil did not decrease greatly when sanctions and the international blockade on Iran tightened as was the case during 2012 and 2013. The following graph (Figure 3) also shows that imports decreased by about 20 percent during these two years and then returned to their previous levels in 2014 and 2015, two years before the activation of the nuclear agreement. Although China’s imports of Iranian oil have fallen by more than 50 percent after the US ended its sanction waivers , in the long run they are likely to compensate this decline in the future.

Figure 3: China’s Imports of Iranian Oil (2011-2016)

In May 2018, after the American withdrawal from the nuclear agreement, China declared its opposition to US sanctions from day one. It considered these sanctions unilateral and did not recognize them. China was the first destination of Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif. Based on this clear position, trade and oil relations between the two countries continued but were centered on the companies linked to the Chinese government more than the Chinese private sector. When the major European companies left Iran after the American withdrawal from the nuclear agreement, major Chinese companies such as the Chinese National Oil Company CNPC purchased the share of the departing European companies such as the French company Total. It withdrew from the contract to develop the Iranian South Pars gas field worth $5 billion in 2017. Thus, the CNPC purchased 80 percent of this contract.[16]*

When the United States imposed sanctions on Iranian oil buyers in November 2018,[17]* China rejected them and continued to be Iran’s largest trading partner by supplying it with goods and importing Iranian crude oil in exchange. Although its import quantities decreased by 60 percent, they did not drop to zero, unlike other countries including Japan that upheld the American objective to decrease Iran’s oil exports to zero in order to avoid US sanctions.

For more than two decades, China has obviously succeeded in gaining the confidence of Iran’s leadership in spite of the challenges and impediments that have impacted economic relations between them at times. Any observer of the size of the partnership and the level of economic cooperation between both countries can see the depth of trade cooperation between them stemming from their common interests and the importance of both parties to each other. This factor – common interests – will ensure the sustainability of economic relations between both countries in the future as long as this equation exists. In addition, each party is of strategic and economic importance to the other as will be discussed below.

2. Cooperation at the Political and Strategic Levels

The common interests between China and Iran extend to the political level:

A. The common vision towards the nature of the international system: The two countries have a similar vision in relation to the growing risks posed by the unipolar international order to their regional and international interests. Both countries believe in the importance of establishing a “multipolar” world to create space for the emergence of rivals and influential actors in international affairs.

Despite the great economic mutual interests between China and the United States, Beijing rejects global American domination. Iran firmly adopted the view 40 years ago that the United States is the “Great Satan” and Israel the “Little Satan.” Both countries share the same view in regard to the unipolar international system and its attempt to target and encircle them as well as to limit their powers regionally and internationally.

B. Cooperation to address the American encirclement policy: The collective Chinese-Iranian consciousness centers on the fact that they are victims of the Western encirclement policy towards China in East Asia and Iran in the Middle East. Iran was divided into several Russian and British spheres of influence in the 19th century, and it was exposed to American and British pressure to discourage it from cooperating with the communist regimes and to pursue Western interests in the early 1940s. Iran was and still is facing a series of stifling economic sanctions. China experienced a series of consecutive military defeats from Western powers. It was under international sanctions led by the United States after it established the socialist system in the late 1940s. As a result, the two countries hold the same view in blaming Western European and American powers for their problems.

The Chinese-Iranian mindset is fully aware of the need to engage in joint coordination to address East Asian and Middle Eastern issues and form a strong geo-economic and strategic balance to confront the common threat of the US policy in the two regions. In East Asia, this is within the framework of the United States’ strategic alliance with South Korea and Japan, while in the Middle East it is within the framework of the strategic alliance with Israel and its traditional allies.[18]

C. Mutual strategic need: Together with the importance of the two countries to each other economically and commercially – China is the main buyer of Iranian oil mitigating the impact of US sanctions and Iran is a reliable supplier of oil – Beijing and Tehran are in a state of mutual strategic need.

1 -Iran needs the Chinese veto as a second international strategic balance after the Russian veto to protect its interests from American threats and sanctions. The Iranian strategic mind is always concerned about the continuation of Russian support which has led to historical mistrust between the Iranians and Russians. This is due to the fact that the Russians seized parts of Iranian territory during the period of the Qajar dynasty between 1813-1828, occupied Iranian lands during the Second World War, and supported the separatist movements in the Iranian Kurdistan and Azerbaijan regions, which Russian President Vladimir Putin himself acknowledged by announcing during his meeting with Khamenei in November 2017, “We will not betray you [Iran].”[19] In addition, a great deal of tension emerged in Russian-Iranian relations in relation to the Syrian file, which escalated to armed clashes between pro-Russian groups and Iranian-backed militias in Syria over areas of influence.

2- China considers Iran a strong alternative and a reliable ally to counter American policies in the Middle East. Iranian opposition to American hegemony is based on ideological grounds for the Islamic Republic. Therefore, there is a strategic value for China in helping Iran to develop its capacities so that it can counter US hegemony over the region’s resources. Russia’s help to Iran is a real opportunity and a gateway to secure China’s strategic foothold in the Middle East[20] and Central Asia. It also gives China a pressure card against the United States in the Middle East while the United States has pressure cards against China in East Asia.

D. The compatibility between some Middle Eastern and East Asian files: The two countries converged on the Syrian file and to keep President Bashar al-Assad in power. Iran provided military, financial, and political support to keep Assad in power. The Chinese veto curbed the imposition of international sanctions against Assad. They also converged on the North Korea file against US policies. Chinese President Xi Jinping also called on Iran in 2019 to jointly stifle the three forces: terrorism, separatism and extremism, including the East Turkestan Islamic Movement.[21]

3. Military Cooperation

Military cooperation between the two countries dates back to the 1980s when China was added to the list of Iran’s arms suppliers during the Iran-Iraq War (1980–88). Beijing exported to Tehran ballistic missiles, including Silkworm anti-ship missiles. Thus, China was the largest military supplier to Iran during the 1980s. Iran will never forget the Chinese favor because the arms were delivered at a very critical time after the arms embargo was imposed on it due to the American hostage crisis in 1979.

The Chinese role extended beyond this and it played a central role in developing Iran’s nuclear program during the 1980s and 1990s. Beijing assisted Tehran in building the Isfahan Center for Nuclear Research, which opened in 1984, and trained Iranian nuclear engineers and taught them how to extract and enrich uranium. In 1990, China also shipped to Iran a ton of uranium hexafluoride gas, which is important to pump gas to centrifuges.[22]

Although China ended its support for the Iranian nuclear program in 1997 in an attempt to improve its relations with Washington, it supplied Iran from 2002 to 2009 with weapons such as C-801 and C-802 anti-ship and cruise missiles and QW-11 portable surface-to-air missiles.[23] During 2010, China helped Iran build a factory for Nasr-1 anti-ship missiles, and anti-ship cruise missiles Noor, an upgraded version of the Chinese missile C-802 with a range between 120 kilometers to 220 kilometers.[24]

Tehran has received Chinese assistance to develop ballistic missiles capable of launching satellites into space via its membership in the Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization. China conducted joint military manoeuvres and exercises with Iran in 2014, 2017 and 2019 in the waters of the Arabian Gulf. In 2015, the electronic defense company SA Iran signed contracts with Chinese companies to benefit from the Baidu-2 system navigation satellite for military purposes. This system provides more accurate services than the GPS system, which advances and improves Iran’s ability to use satellite navigation in its missiles and drones.

As the October 2020 expiration date of the UN embargo on Iran to sell and buy weapons under resolution 1747 draws closer, China remains one of the most important candidates to enter into a massive military partnership with Iran via supplying it with weapons to develop its conventional arsenal. A report by China Daily revealed that Iran could benefit from Chinese military industries in the air, land, and sea spheres. For example, the modern Chinese J-10C could play a role in developing and modernizing the ageing Iranian air force. Iran could also benefit from some Chinese products including fast attack cruisers Type-02, anti-aircraft cruise missiles YJ-22, Yuan submarines,and the HHQ-10 (FL-3000N) anti-aircraft missile system. Beijing can also provide technical support to Iran to operate and maintain these systems.[25]

China was classified as the second largest arms exporter to Iran after Russia up until the arms embargo in 2007, and was a strong candidate to sell arms to Iran after the embargo expired, especially in light of the historical mutual trust between China and Iran and the need for geopolitical and economic cooperation between the two countries.

III- The Constraints on the Development of Relations and the Chinese -Iranian Divergence

Although the level of cooperation between China and Iran is described as ‘an understanding and partnership,’ obstacles to relations and issues of divergence limit the cooperative relations between the two important countries regionally and internationally as follows:

1. Economic Sanctions on Iran and China’s Pragmatic Behavior

The economic cooperation between the two countries does not mean that bilateral economic and trade relations were always seamless during the partnership phase since 2006, which is still ongoing. However, Chinese companies suspended the implementation of huge agreements valued at about $20 billion to develop the South Pars field in 2011 in fear of international sanctions. The behavior of some Chinese companies has angered Iranian officials in the absence of competition, especially from the Europeans. In 2015, the former Deputy Minister of Economy Mohsen Farhani said that Chinese companies imposed new conditions as a result of the embargo and due to the absence of competition raised the prices of their exports and delayed delivery dates. Iranian manufacturers felt compelled to use Chinese products. [26]

This Chinese behavior may explain why the volume of joint trade between the two countries in 2015 and 2016 declined by approximately 7 percent. At the same time, trade between Iran and the European countries witnessed a fourfold increase in a bid to end Chinese hegemony over the Iranian market, creating opportunities for new competitors after the lifting of sanctions in January 2016 (see figures 1 and 2). The move towards Europe was also prompted by Iran’s urgent need for more advanced technology which European industries can provide. However, China has remained the world’s largest buyer of Iranian oil, although import quantities have decreased.

China’s Bank of Kunlun was the main banking channel to pay for Iranian oil and trade between the two countries since 2010, and it is a bank owned by the Chinese government largely through CNPC.[27] The Chinese government authorized the bank to act as a financial channel and to protect other Chinese banks from sanctions imposed on Iran. Although the United States imposed sanctions on it in 2012, this bank continued to play its role and facilitate the movement of goods and oil between the two countries. However, it seems that the bank is no longer able to play the same role now after the reimposition of US sanctions because the owner of the bank expanded its investments in the US market[28] which makes the bank vulnerable to US sanctions. Therefore, the bank quickly announced that it has limited the deal with Iran to humanitarian trade (food and medicine only) until the sanctions are lifted.

Another constraint on the development of relations between the two countries is the current trend of the Chinese financial sector toward upgrading its financial systems and abiding by international transparency standards and the requirements of the anti-money laundering rules and regulations to combat terrorist financing developed by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).This agreement sparked widespread controversy in Iran and it has refused to join it to date.

Indeed, these obstacles are reflected in the current levels of trade between the two countries. The volume of trade exchange also declined following the reimposition of US sanctions. In January 2019, Iran’s exports to China decreased by about 50 percent compared to the same month in 2018, while China’s exports to Iran decreased by about 60 percent during the same period. Thus, if China does not find alternative ways to trade safely with Iran such as dealing with small banks, the volume of economic and trade cooperation between them will surely decrease even more, according to statements by Chinese officials.[29]

2.The Divergent Economic Interests With the United States

There is a difference between China and Iran in relation to their economic interests with the United States. While China has extensive economic and trade relations with the United States, Iran’s economic relationship with the United States has come to a halt. The Chinese approach to dealing with the American position on Iran is determined somewhat by Washington’s desire to maintain strong trade relations with China. However, Iran cannot adopt a similar approach to China in dealing with the United States due to the complete severance of US-Iranian ties.

3. The Divergence in Foreign Policy

While revolutions erupted in both countries leading to a decline in Western values in the two countries, China did not adopt revolutionary thinking to drive its foreign policy. Rather, its foreign policy shifted to depend on pragmatism as the international system shifted to unipolar leadership with national interests taking center stage in international relations instead of ideological differences. China’s major concern is economic development, from any source and by any means, whether assistance is provided by the former Communist Russia, and imperial Japan that attacked it in the past, or the United States, China’s current rival. Here, the statement of Deng Xiaoping holds deep resonance, “I don’t care if the cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice.”[30] This approach has prompted China to engage in cooperative relations with various international actors including the United States and Israel, the archenemies of Iran. Thanks to its cooperative policies, China’s economy is ranked second in the world. However, Iran relies on a revolutionary, ideological approach.

The revolutionary and ideological approach, the expansionist theory of the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist, has been one of the most important drivers of Iranian foreign policy since 1979 via which Iran identifies its allies and opponents. This has created hostilities with many countries at the regional and international levels, which has prompted Iran to enter into conflictual and confrontational relations with many countries in the region and the world and to sever its relations with the United States and Israel. Iran has also turned into a country which suffers from economic crises and international isolation due to its interference in the internal affairs of other countries as well as it not respecting the principle of good neighborly relations and national sovereignty due to its revolutionary alignment as mentioned in its constitutional provisions, in particular Article 154.[31]

4. Divergent Views Over Middle Eastern Issues

There are divergent views over issues such as nuclear proliferation and Iranian threats to close the Strait of Hormuz. Beijing rejects the proliferation of nuclear weapons in general because of its potential catastrophic impact on Chinese international commercial interests and oil tankers coming to China, as well as Iranian threats to close the Strait of Hormuz to oil tankers coming to China through it or to Chinese merchant ships loaded with goods. If this strait is closed, China will inevitably be harmed.

IV- Iran as a Bargaining Chip Between China and the United States

With the end of the second decade of the third millennium – a decade which was full of unprecedented transformations in contemporary history – there were milestones with a more polarizing impacr among international units. At the end of this decade, the American demand to extend the arms embargo on Iran under Security Council Resolution 1747 faced a Chinese and Russian veto. This was due to the growing intense polarization and sharp divergent interests of the permanent members of the Security Council since the American withdrawal from the nuclear agreement in 2018.

A great deal of analysis reveals that the Chinese veto blocking the extension of the arms embargo on Iran is due to several factors, most importantly as follows:

A. China rejects the US strategy of maximum pressure against Iran and it still complies with the agreement which stipulates the lifting of the arms embargo in October 2020.

B The United States ignited a trade war against China at the beginning of 2018 by imposing tariffs directly on Chinese imports and through sanctions on China’s major energy suppliers.

C. Some intelligence reports indicated that Beijing and Moscow concluded arms deals with Iran that will be implemented as soon as the embargo expires[32] which will provide China and Russia with billions of dollars. In that case, how can the two countries be discouraged from using the veto to extend the embargo, especially after Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov announced that Moscow will not accept the extension of the ban?

D. There is a shift in international power levels, contrary to what prevailed at the beginning of the century. The great power difference was in favor of the United States over the rest of the international actors. By 2020, this is completely different because the power difference has declined dramatically among the international actors, as China and Russia have taken up advanced positions in the international system as was indicated by their responses/reactions to the outbreak of the coronavirus in 2020.

The factors prompting the Chinese or Russian veto on the decision to extend the arms embargo may seem logical and increase the issue’s complexity while making it more difficult for the United States to exert pressure to extend the embargo. The decision to extend the embargo depends on the price Washington is willing to pay, which will not be low, to Russia and China to discourage them from using the veto against the decision. China and Russia in 2020 are not in the same position as they were in 2000 in terms of their level of influence in international affairs.

The Russians refused to extend the embargo on Iran. The Russian Foreign Ministry noted in March 2020, “It was said in Congress that the United States will try to persuade Russia and China not to veto the draft UN resolution on extending the arms embargo on Iran. But there is no use in raising this issue.” In its statement, the ministry added, “The United States presents its multibillion dollar arms deliveries to the Middle East.”[33] This statement was a very important sign of reciprocity on the issue of selling arms to the region’s countries, but there is a great difference between selling weapons to responsible countries that use them to deter threats and to irresponsible countries such as Iran that use them as a direct threat.

Therefore, American calculations to achieve international consensus on the issue have become overly complicated. The fluctuating European position to extend the ban has further complicated US calculations as indicated by Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov. He said, “European countries that signed the deal – including Britain, Germany and France – do not have the intention to refer Iran’s file to the Security Council.”[34] How will these countries agree to extend the embargo on arms sales to Iran which conflict with the terms of the nuclear agreement while opposing the American withdrawal from the agreement and seeking to create a cooperation mechanism with Iran to discourage it from withdrawing from the nuclear agreement? This is what the US secretary of state acknowledged by saying, “If we are unable to urge others to act, we will consider closely all options to achieve that.”[35]

Hence, the issue is mainly related to what Washington will offer to the signatories of the nuclear agreement to achieve an international consensus to extend the embargo. This is difficult under an American administration that adopts inflexible policies on outstanding issues. The US administration may threaten further sanctions against China and hold it responsible for the potential risks of Iran’s growing power that threatens the security of the region which China relies on to import oil. China is concerned about Iran’s growing power, which increases the Iranian threat and harms Chinese interests. The next few months will reveal whether the decision to extend the arms embargo on Iran is accepted or rejected. The whole issue has become extremely complicated and unclear.

V- Conclusions

In light of the determinants of strength in Chinese and Iranian relations and their cooperation and divergence, the Chinese position on the UN arms embargo canbe reviewed as follows:

1. Success in Building Multifaceted Strategic Relationships

What brings China and Iran together is far greater than cooperation in the spheres of energy and trade. Chinese-Iranian cooperation is also linked to the central goal of Chinese foreign policy; to spread its influence peacefully across the world and transform the international system to a multipolar one, ending US hegemony over the international system and gaining a foothold in the Middle East which will limit American influence and serve Chinese interests. Iran is thus important to China in the region, and even to the Silk Road project generally. Even if it is a cross-border trade route, it is one of the most important Chinese mechanisms to pull the rug out from under American feet to end its international domination. This road is also associated with the Iranian goal to reduce US hegemony and to gain a reliable international ally that can counterbalance the United States and limit its pressure and serve as a source of international protection.

2. Establishing a Relationship Outside the Boundaries of American Influence

American options and pressure cards toward China to reduce the level of its relations with Iran have limited influence. The United States’ use of penalties against Chinese companies and trade have become ineffective due to China’s economic strength, which is ranked second in the global economy, and its political weight, veto power, and growing military budget which has reduced the gap in in military expenditures between international powers. Successive US administrations have failed to shape China’s approach in dealing with the Iranian file to serve US policies and sanctions on Iran.

3. A Permanent Economic Relationship and Greater Gains for China

Chinese-Iranian trade cooperation will continue to exist in the future, and could be developed further, provided that safe mechanisms are established for financial exchange between the two countries. Banking obstacles will undoubtedly hinder the increase in the volume of trade exchange between the two countries unless China succeeds in finding alternative ways to continue working with Iran through a group of small Chinese banks. It is possible that economic relations will tend to serve Chinese interests more than Iranian interests as long as US economic sanctions remain in place. China’s growing role within the Iranian economy will increase its influence over Iranian decision-making, particularly in light of the limited alternatives and options available to Iran. This may result in the Iranians being in a weaker position in relation to trade negotiations between the two parties. Iran will also have to accept lower quality technology and equipment for its oil and industrial sectors, compared to fleeing European investments, which will ultimately impact the competitive nature of Iranian products. On the other hand, for China, the period of US sanctions on Iran will be a good opportunity to obtain more concessions in relation to the purchase of Iranian oil and the development of gas production and exports in its favor in addition to trade and securing investment opportunities in the Iranian market.

4. Iran’s Failure in Taking Advantage of the Chinese Model

Despite the strong strategic relations between China and Iran, and that China is Iran’s closest international ally, the latter failed to benefit from the former in seeking the ideal scenario to build strength and achieve its goals without being involved in conflict. The time period of China’s economic transformation almost coincides with the rule of the supreme leader in Iran. The Chinese experience was initiated by Deng Xiaoping in 1978, while Iranian clerics tightened their grip on power after the revolution in 1979. China gave up the ideological dimension in its foreign policy more than 40 years ago because this dimension led it to adopt a confrontational position against many countries of the world and placed it on the list of the world’s poorest countries. China adopted the pragmatic dimension that turned it into the world’s second-largest economy. Nevertheless, Iran did not learn from China’s approach and upheld the ideological dimension after China abandoned it due to its catastrophic repercussions on its internal and external conditions which created conflictual relations with many regional and international powers. Iran now experiences what China did four decades ago, despite the changes in the regional and international systems.

Conclusion

Considering the foregoing, it can be said that it is difficult to influence Chinese-Iranian relations. It seems that any change is is dependent on the nature of the their political systems and the extent of their mutual strategic, geopolitical, economic, and military need for each other. This is in addition to the escalation of US-Iranian tensions toward war. This scenario is difficult to envision given the disastrous consequences of war for all the parties concerned. This makes the cost for China to maintain its relations with Iran very high compared to Beijing lowering the level of its relations with Iran. In the absence of these unlikely changes, China will maintain its stance on Iran and its refusal to withdraw from the nuclear agreement and the economic sanctions imposed on Iran.

As much as China recognizes the importance of Iran as a reliable trade and political ally in the Middle East, Beijing also understands that insecurity in the Arabian Gulf will inevitably risk its interests with the United States in the strategic and vital Arabian Gulf region. Instability in the Middle East threatens Chinese trade ships and energy supply lines, making China prefer the collective security option in the Arabian Gulf in light of the strategic importance of the Gulf states and Iran to China. China is making efforts to secure energy resources from the Caspian region as an alternative to Middle Eastern oil. Therefore, Iran is a vital link for the transit of oil pipelines to transfer energy from the Caspian region to China, indicating that China has a strong interest in maintaining a strong strategic partnership with Iran.

[1] Bonnie Girard, “The History of China and Iran’s Unlikely Partnership,” The Diplomat, accessed April 24, 2020, https://bit.ly/36eICiZ

[2] Peter Mackenzie, “A Closer Look at China-Iran Relations , Roundtable Report,” CNA China Studies, accessed April 24, 2020, https://bit.ly/2Re0Coj

[3] Scott Harold and Alireza Nader, “China and Iran: Economic, Political and Military Relations,” RAND Center for Middle East Public Policy, OP-351-CMEPP, 2012, accessed April 30, 2020, https://bit.ly/3dVrDot.

[4] “Trump Abandons Iran Nuclear Deal He Long Scorned,” The New York Times, accessed April 24, 2020, http://cutt.us/ZCmVd

[5] “Iran Proven Oil Reserves by Country (2020),” Global Fire Power, accessed April 30, 2020, https://bit.ly/2KVaZJ4

[6] “Rouhani Reveals the Oil Fields in Astan, Khuzestan,” BBC (Persian), April 30, 2020 accessed, May 26, 2020, ، https://bbc.in/2Wqj91l.

[7] “The Syrian Badia War Conceals a Conflict Over the Silk Road Crossings and Oil and Gas Fields,” ERM News, May 31, 2017 accessed April 20, 2020, https://bit.ly/36uaNu9

[8] “Iran, China Sign 17 Cooperation Documents/ Issuing 5-Point Statement on Tehran-Beijing Strategic Partnership,” accessed April 20, 2020, https://bit.ly/3c3tB4F. [In Persian]

[9] Harold and Nader, “China and Iran: Economic, Political and Military Relations,” 4.

[10] Abdelraouf Mustafa Jalal, “The Rise of China and American Encirclement Policies,” (Cairo: Egyptian Visions Magazine, al-Ahram Center for Social and Historical Studies), no. 58 (November 2019): 16-22.

[11] “2018 Military Strength Ranking,” Global Fire Power, accessed April 30, 2020, https://bit.ly/3d33GeP

[12] “How We are Organized,” Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank AIIB, accessed May 20, 2020, https://bit.ly/3eexdlV

[13] John W. Garver, China and Iran: Ancient Partners in a Post-Imperial World (Abu Dhabi: The Emirates Centre for Strategic Studies, 2009), 357. [In Arabic].

[14] Ibid., 368-369.

[15] “Direction of Trade Statistics, Exports, FOB to Partner Countries,” IMF, accessed May 26, 2020 https://bit.ly/2yxv85.

[16]* In October 2019, China withdrew from the project, but China will unlikely leave the Iranian oil market, especially the field of natural gas production, which it pays particular attention to in order to reduce its high level of air pollution.

[17]* The first stage of the sanctions were imposed on August 6, 2018, including on Iran’s dealings in the US dollar, the mineral trade and spare parts . The second stage was imposed on the buyers of Iranian crude oil and its derivatives on November 4 of the same year. Other sanctions related to transportation, insurance and ports.

[18] “China Backs Iran Nuclear Deal as United States Walks Away, but Could it Be a Costly Decision?” South China Morning Post, http://cutt.us/FfGke

[19] “Russian President Vladimir Putin Meets Iran Supreme Leader,” RT Arabic, accessed May 20, 2020, http://cutt.us/szW2z

[20] John W. Garver, “Is China Playing a Dual Game in Iran ?”accessed May 20, 2020, http://cutt.us/Wneyt

[21] “Chinese President: We Are Willing to Cooperate With Iran Despite the Changes in Regional and International Conditions,” Italian news agency Aki, accessed April 20, 2020, https://bit.ly/35Y8U93

[22] David Albright and Andrea Stricker, “Iran’s Nuclear Program,” United States Institute of Peace, The Iran Primer, October 6, 2010, accessed May, 20.2020, https://bit.ly/2zaIVer.

[23] Robert F. Worth and C. J. Chivers, “Seized Chinese Weapons Raise Concerns on Iran,” The New York Times, March 2, 2013, accessed April 20, 2020, https://nyti.ms/3icW6Rf.

[24] “China Opens Missile Plant in Iran,” UPI, April 23, 2010, accessed May 20, 2020, https://bit.ly/2EciHMb

[25] Mervat Zakaria, “Will China strengthen Iranian Military Capacity in 2020?” Arab Center for Research and Studies, January 26, 2020, accessed May 20, 2020, https://bit.ly/3chsCi1

[26] Najmeh Bozorgmehr, “China Ties Lose Luster as Iran Refocuses on Trade With West,” Financial Times, September 23, 2015, accessed May 20, 2020, https://on.ft.com/2ViDKGl

[27] “Banking Restrictions Take Toll on China-Iran Trade,” Financial Tribune, accessed May 20, 2020, https://bit.ly/2P9Vdgu

[28] Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, “Why China Isn’t Standing By Iran,” Bloomberg, March 1, 2019, accessed May 20, 2020, https://goo.gl/8haF3h

[29] “Disconnecting the Link Between the Company and the company,” Mashregh News, accessed May 26, 2020, https://bit.ly/33PWi1s.

[30] Ibrahim al-Akhras, China Ideological Background and Pragmatic Utilitarian, (Cairo: Dar al-Ahmadi, 2006), 67-106.

[31] The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran , Article 154.

[32] Anton Mardasov, “Iran’s Military After UN Arms Ban Ends?” Al-Monitor, March 9, 2020, accessed April 20, 2020, https://bit.ly/3dHEjPF

[33] “Arming Iran: New Conflict Between the United States and Russia,” Riyadh Post, March 10, 2020, accessed April 20, 2020, https://bit.ly/2yTNLk7

[35] “US Secretary of State: We Are Considering All Options to Extend the Arms Embargo on Iran,” Monte Carlo International, 29 April, 2020, accessed April 30, 2020, https://bit.ly/35RVnzA