Introduction

For nearly four decades, Arab countries have repeatedly called on regional and international actors to take responsibility for overlooking the dangers posed by violent non-state actors to security and stability. Over the past 20 years, they have also put forward constructive approaches to mitigate these threats, emphasizing geographical proximity and the militia-driven logic that defines these groups. Now, decision-makers in both the East and West have come to recognize the credibility of the Arab and Gulf perspective on the long-term risks associated with the proliferation of such actors in the Middle East. After years of neglecting these warnings, they find themselves grappling with the consequences, forced to confront these threats head-on and bear the high costs of countering them. However, it was only when their own interests were directly harmed, their allies’ security was jeopardized and the cost of confrontation became unavoidable that they began to acknowledge the destabilizing effects of these groups, which have turned affected Arab states into hotbeds of crises, threats and insecurity.

The shifting regional landscape, marked by the arrival of a new US administration opposed to violent non-state actors, presents a historic opportunity to develop pragmatic and effective strategies to curb their influence. This could set the stage for either neutralizing these groups or integrating them into localized structures, leading to an irreversible shift away from their destabilizing role. Such an approach would bolster the resilience and authority of the nation-state, particularly as the countries hosting these actors — such as Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, Sudan and Libya — have devolved into failed states. These countries are now plagued by complex conflicts, prolonged crises and conditions that provide safe havens for terrorist and extremist groups. The resulting humanitarian disasters, including soaring displacement rates and unregulated mass asylum, have only deepened. Meanwhile, the unchecked proliferation of arms and escalating hostilities between local and regional actors continue to pose serious threats to international trade and maritime security.

This study aims to analyze and assess the rationale behind proposed strategies for addressing the challenges posed by violent non-state actors, specifically the Iran-backed militias operating in Iraq. The ultimate goal is to secure the Iraqi state’s monopoly over arms by dismantling these groups and curbing their influence both domestically and internationally. Iraq has become a focal point of regional and global efforts to control the spread of weapons, mirroring past experiences in Lebanon and Syria. This focus is driven by sustained US pressure on the Iraqi government to weaken Iran’s armed proxies and reinforce the principle of state control over weaponry. However, the core issue is not merely expert assessments on whether these militias can be partially or fully dismantled. Instead, it lies in the institutionalization of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) within Iraq’s armed forces, effectively functioning as a parallel or alternative army —much like Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

The study raises several key questions regarding the historic opportunity* to establish the Iraqi state’s monopoly on weapons. Chief among these: do the proposed approaches genuinely achieve this goal, even temporarily, as seen in Lebanon and Syria? Or are they merely partial, short-term measures that address the symptoms rather than the root cause?

It also examines the deeper complexities of violent non-state actors and their resistance to conventional solutions. Does the challenge primarily relate to integrating the PMF into the national army as a unified body? Or does this challenge extend to the dissolution and integration of the unruly militias that operate outside even the PMF’s framework? Alternatively, is the real obstacle a fundamental misunderstanding of the militia-driven logic that dominates Iraq?

Beyond these questions, the study explores whether realistic and constructive solutions exist that could help the Iraqi state regain full control over arms and break free from the influence of violent actors. If such solutions are viable, can a concrete implementation strategy be developed? Furthermore, what are the strengths, weaknesses and limits of the various parties involved in Iraq’s entrenched militia system? Finally, given the current historic opportunity, how can efforts to dissolve the PMF be effectively advanced?

Critical View of the Approaches Related to the Violent Actors in Iraq

Decision-makers in Washington and Tel Aviv have increasingly focused on Iraq, viewing it as the next target in broader US efforts to weaken Iran’s influence in the Middle East. This comes amid concerns that pressure on Iraq could escalate with the start of a second term for US President Donald Trump, known for his staunch opposition to militias. Trump might consider a military response or grant Israel greater latitude to strike militias in Iraq if the Iraqi government, led by Mohammed Shia’ al-Sudani, fails to meet US demands to establish a state monopoly over weapons possession.

Against this backdrop, discussions within US, Israeli, Iranian and Iraqi decision-making circles have placed the issue at the forefront of global media attention. The following outlines the key proposed approaches to addressing the challenge of violent non-state actors in Iraq.

A Partial Dissolution of Some Unruly Militias*

During former US Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s unannounced visit to Baghdad on December 13, 2024, Washington presented the Iraqi government with a proposal urging Prime Minister Sudani to take strict measures against unruly militias.[1]

According to multiple media reports, the proposal centered on a partial solution: pressuring the government to dismantle three militias operating under the banner of the “Islamic resistance” in Iraq. These groups had participated in the war alongside Hamas to counter Israeli military operations in Gaza until the ceasefire was declared. They were also accused of carrying out attacks on US targets in Iraq. The targeted factions included Kata’ib Hezbollah led by Abu Hussein al-Hamidawi, Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba led by Akram al-Kaabi and Kata’ib al-Shuhada headed by Secretary-General Abu Alaa al-Wala’i, also known as Hashem Finyan al-Saraji.

The proposal has ignited debate among think tanks, highlighting its failure to understand the dominant militia dynamics in Iraq and its inability to curb Iran’s influence in the country. Experts argue that the real issue is not the disbanding of three militias or all unruly militias, but rather the PMF, a formidable faction within the Iraqi army that functions as a parallel force similar to the IRGC. As a result, many view the proposal as inadvertently supporting Iran’s efforts to shift focus away from the core issue: dismantling the PMF and reintegrating it into the Iraqi military through a new approach, rather than the previous integration process. Disbanding three militias, or even all rogue groups, will not diminish Iran’s power in Iraq as long as the PMF exists in its current form. Iran could easily restructure the three militias under new identities or fold them into the many other militias operating within Iraq, thus maintaining its influence.

Total Dissolution of All Unruly Militias

A potential US proposal, introduced by the Trump administration as part of a broader strategy to eliminate Iranian influence in Iraq, calls for the complete disbandment of unregulated militias rather than a partial dismantling. This approach aligns with the views of Gabriel Soma, a member of President Trump’s advisory council, who emphasized that the president aims to eradicate all Iranian influence and prevent the militias from targeting Israel under any circumstances. The proposal also reflects the statement of Iraqi Parliament Speaker Mahmoud al-Mashhadani, who revealed that Trump had urged Sudani to limit the possession of weapons to the state. Additionally, several media outlets reported that Blinken conveyed a message from Trump to Sudani,[2] urging him to take action to control militia activities, restrict their movements and prevent their interference in Syria.

During a phone call with Sudani on February 25, 2025, the current US Secretary of State Marc Rubio delivered stern warnings to the Iraqi government. According to a statement from the US embassy in Baghdad,[3] Washington demanded that Iraq curb what it described as malignant Iranian influence, ensure its energy sector’s independence and uphold contractual agreements with US companies to attract further investment. Rubio also stressed the importance of continued consultations on regional affairs, strengthening US-Iraq security cooperation and joint efforts to prevent the resurgence of ISIS and broader regional instability. The call took place amid growing Iraqi concerns over potential US sanctions, which could target specific entities, banks or individuals.

While Democrats have largely focused on pressuring Baghdad to curb militia activities, Trump is expected to take a far more hardline approach if Iraq fails to enforce state control over weapons. This could lead him to threaten military action — either directly or by granting Israel the green light to replicate its past operations against Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Such a move would aim to dismantle the military capabilities of all factions within the so-called Axis of Resistance and prevent them from participating in future regional conflicts with Israel. Trump’s particularly hostile stance toward Iran-backed militias in Iraq suggests he may pursue more aggressive measures to weaken their influence.

Many observers anticipate that Trump will adopt an approach aimed at weakening Iranian influence in Iraq by setting a specific deadline for the disarmament of militias, coupled with intense pressure on the Iraqi government. He is expected to leverage a range of financial, economic, political and military pressure tactics against Iraq — targeting its banks, financial system, oil sector and key militia-aligned military and political figures.

However, as of the study’s publication, there is no indication that the United States under Trump intends to dissolve the PMF. If Washington formulates a strategy to counter Iran in Iraq, the core issue will not be merely disbanding, disarming or integrating militias into the PMF. Rather, it lies in the PMF being a parallel army to Iraq’s official military.

Total Dissolution of the PMF

This reflects an Israeli perspective, as i24News — known for its close ties to the government — offered an alternative interpretation of Washington’s demands to Sudani. According to the network, the United States is not only calling for the dissolution of uncontrolled militias but also for the dismantling of the PMF itself.[4] This narrative contradicts reports in the Iraqi and Arab press regarding the behind-the-scenes negotiations between Washington and Baghdad. Israel’s stance may stem from its understanding of Iraq’s prevailing militia logic, which places the core issue within the PMF as an integrated entity within Iraq’s armed forces. However, the Israeli press has not proposed any new framework for dissolving the PMF or reintegrating its fighters into the army — likely because such a move is neither practical nor feasible.

Integrating PMF Fighters Into the Iraqi Army

An Iranian proposal — circulated in the media during Quds Force Commander Esmail Qaani’s visit to Iraq on January 7, 2025, where he met with Sudani and militia leaders — suggested that Sudani issue a decision to fully integrate thousands of PMF fighters into the Iraqi army.

This plan would replace the current arrangement, under which the PMF maintains financial and military ties with the armed forces while enjoying administrative independence and implementing its own orders. Instead, PMF fighters would wear official army uniforms and adhere to the military chain of command.[5] The proposal aimed to achieve several objectives:

Circumventing Dissolution Demands

By integrating the PMF into the army under an Iranian-defined framework, Tehran seeks to ensure its continued existence as a distinct entity. This preemptive move is designed to shield the PMF from mounting US and Israeli pressure, which could otherwise force Baghdad into a swift dismantling of the group — similar to what happened to its counterparts in Syria and Lebanon.

Blurring Distinctions Between Army and PMF Fighters

By granting PMF members official military status, including army uniforms, Iran aims to make it difficult for adversaries to distinguish between regular forces and PMF units. This would reduce the risk of targeted US or Israeli military action against PMF fighters, particularly under the prevailing Trump presidency.

Mitigating Internal Disputes

The proposal also serves to prevent tensions between Sudani and Coordination Framework leaders over the PMF’s future. With Sudani under increasing pressure to resolve the issue of violent non-state actors, this integration plan would provide him with a means to navigate both domestic and external demands without triggering a major confrontation.

Maintaining Coordination Framework Unity Against US Pressure

The proposal aims to prevent divisions among Iran-aligned Coordination Framework leaders regarding how to respond to escalating US demands. Any internal discord could weaken the bloc’s influence within Iraq’s political landscape. By fostering a unified stance, the Coordination Framework can focus on strategies to shield the PMF from external threats.

One suggested tactic is the transformation of targeted militias into political entities. Given that these militias have become highly exposed and are now considered liabilities rather than assets, their direct military role may no longer be viable. Instead, shifting them into political fronts could offer a way to preserve their influence while reducing their vulnerability to US and Israeli retaliation.

Iran’s maneuver to prevent the dissolution of the PMF — which it views as a crucial red line in maintaining its regional influence — reflects Tehran’s unwavering commitment to its geopolitical project. This was underscored by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei during his meeting with Sudani in Tehran on January 8, 2025, when he stated, “As Sudani stated, the PMF constitute an important element of power in Iraq, and efforts must be made to preserve and further strengthen it.”[6]

Similarly, Ebrahim Azizi, head of the National Security and Foreign Policy Committee in the Iranian Parliament, reinforced this stance during a meeting with an Iraqi tribal delegation, “The dissolution of the PMF aims to strengthen terrorist groups in the region.[7]

These statements highlight Iran’s insistence on keeping the PMF intact, despite growing pressure from the United States and its allies.

However, the various proposals for consolidating state control over weapons in Iraq remain political and partial rather than comprehensive. These constitute temporary palliatives that, while offering short-term fixes, may lead to strategic miscalculations with long-term consequences. At the core of the issue is a lack of understanding of the prevailing militia logic in Iraq — a fundamental gap that prevents the formulation of realistic solutions to fully address the influence of violent actors in Iraqi politics.

The crux of the matter is not merely dissolving the militias — whether partially or completely — but rather the entrenched militia mindset itself, with the PMF serving as its centerpiece. As a parallel army, the PMF remains Iran’s key instrument of influence in Iraq, and any attempt to integrate it into the official armed forces must grapple with the deeper structural and political implications of its existence.

Resolving the Issue of Iraq’s Armed Non-state Actors — Dilemmas and Complexities

The attempts and proposed approaches to addressing violent actors in Iraq are not unprecedented; they have been preceded by multiple initiatives[8] and numerous appeals from Iraqi, Arab and US stakeholders. However, all these initiatives failed because they were detached from the realities of Iraq’s ongoing crisis since 2003.

The fundamental flaw in these approaches lies in their lack of a comprehensive and realistic vision — one that fully acknowledges the deep-rooted and complex nature of the problem. Over the past two decades, Iraq has grappled with a systemic issue that extends beyond the mere presence of militias.

At its core, the crisis revolves around the dominance of group-based logic over state-based governance — a reality that manifests across political, economic, cultural and security dimensions, not just in the military sphere. This entrenched dynamic has shaped Iraq’s trajectory, making any attempt to curb violent actors ineffective unless it directly confronts the deeper structural imbalances within the Iraqi state.

The following are some of the most pressing challenges that must be addressed to achieve a meaningful resolution:

The Prevailing Militia-oriented Mindset

All traditional and current approaches have failed because they overlook the prevailing militia mentality in Iraq rooted in non-state structures and sectarian entrenchment, which fundamentally opposes the principles of statehood, institutional governance, civil rule and national unity.

This militia-driven model is a direct consequence of the sectarian quota system that took hold in Iraq after the 2003 US invasion. Over time, Iraq’s Shiite political system has increasingly aligned itself with sectarian interests, militias and their external patrons, rather than serving as a unifying force for the state.

Unlike in Syria or Sudan, where militias primarily function within a military framework, in Iraq, the militia mindset has infiltrated all aspects of governance and decision-making — political, economic and social. This widespread influence complicates efforts to dissolve the PMF or integrate its fighters into the Iraqi state in a way that prevents them from remaining a cohesive, independent entity within the system.

The PMF is deeply tied to influential political figures and factions in Iraq, many of whom embrace the concept of a militia state as a means to preserve their power and shape decision-making. These factions rely on militias more than official institutions as parallel armies, granting them control over rivals, the state and its resources.

This dynamic explains why Iraq’s power players refuse to disband the PMF — it is not just a military force but a political, legislative, economic and social entity that has embedded itself within the state. The PMF does not see itself as a force to be dissolved but rather as an entity entitled to govern and shape society. Any move to dismantle the PMF would mean losing the privileges, influence and resources it has accumulated over the years —rendering it the biggest obstacle to any political consensus on its future.

Lack of an Executive Mechanism for Confining Arms to the State

The failure of external actors to grasp the underlying logic of militias in Iraq has led to inconsistent and ineffective approaches in dealing with militant groups. As a result, there has been no unified or coherent strategy. Most efforts have centered on the idea of dissolving uncontrolled militias — either fully or partially — as the primary means of ensuring that weapons remain under state control. A smaller number of proposals have called for the outright dissolution of the PMF but without outlining clear steps for what would follow. Meanwhile, Iran has pursued a different approach, advocating for either the integration of militias into the PMF or a more superficial integration, limited to standardizing military uniforms.

The complete or partial dissolution of unruly militias effectively translates into their absorption into the PMF, aligning with Iran’s preferred approach. However, this would shift the balance of power in favor of the PMF at the expense of the Iraqi army. Such a merger risks bolstering the PMF’s dominance, especially given that its ranks had grown to approximately 204,000 fighters in 2023, according to its leader, Faleh al-Fayyadh.[9] This figure surpasses the estimated 200,000 troops in the Iraqi army, as reported by US intelligence the same year.[10] If three of the targeted militias — each estimated to have between 10,000 and 50,000 fighters, with some estimates suggesting numbers as high as 100,000 for groups like Kata’ib Hezbollah — were to be integrated into the PMF at an average of 30,000 fighters per group, the PMF’s total strength would rise by around 90,000, bringing its forces to roughly 294,000 fighters.[11] This would further outnumber the Iraqi army as the PMF’s forces could reach twice the size of the Iraqi army, which ranked 45th globally in 2023.

The proposed solutions have also failed to account for the militias’ amorphous structures and the complexities of their existence. While the PMF has been in place for years, many militias have not fully integrated their fighters into its ranks. Media reports indicate that a significant number of militia members are also government or private sector employees who secretly participate in militia activities. As a result, many fighters remain unidentified, and their locations are not concentrated in clear, targetable camps.[12] Additionally, most militias operate based on ideological commitments rather than conventional military structures, and their actual numbers remain undisclosed.

The PMF’s Ideologically-driven Military Doctrine

A deep divide exists between the military doctrine of the Iraqi army and that of the PMF and unruly militias, making it difficult to implement any proposed solution. The Iraqi army operates under a civilian-oriented doctrine, prioritizing national security. In contrast, the PMF’s doctrine is ideologically driven, rooted in unwavering belief in the principles of Wilayat al-Faqih (Guardianship of the Jurist) and the conviction that the PMF has an ideological role in preparing for the emergence of the “the Infallible Imam,” who is expected to establish a so-called global government of justice.

Therefore, the PMF embraces Iran’s transnational revolutionary ideals, viewing its role in advancing Tehran’s international agenda as a spiritual and religious duty. Its fighters follow the directives of Iran’s supreme leader rather than the Iraqi Armed Forces’ commander-in-chief. The militias primarily serve Iran’s interests rather than those of Iraq, particularly as Tehran remains determined to maintain its influence in Iraq after suffering historic setbacks in Syria and Lebanon. This further complicates any efforts to dissolve the PMF.

An Iraqi study published in late 2021 found that 44 out of 67 militias operating under the PMF — roughly 65% — pledge allegiance to the religious authority in Qom.[13] The PMF’s composition is predominantly Shiite, with Shiites making up 85% of its members, while Sunnis account for just 15%. At the leadership level, Shiites hold full control, occupying 100% of the top positions.[14] Moreover, many of the militias Iran established in Iraq after the 2020 killing of Qassem Soleimani, the former commander of the Quds Force, are directly linked to the IRGC and similarly pledge allegiance to Qom. These groups actively push for the withdrawal of foreign forces from Iraq and often serve as front organizations for long-established militias targeted by US sanctions.[15] Among them are Ashab al-Kahf, Rub’ Allah, Ahd Allah, Liwa Tha’r al-Muhandis, Saraya Qasim al-Jabbarin, Saraya Awliya al-Dam, Asbat al-Tha’ireen, Kata’ib al-Sabireen, Kata’ib Karbala and Kata’ib Sayf Allah. Given these deep-seated ideological allegiances and distinct military doctrines, the prospect of dissolving the PMF remains highly complex.

The Relationship Between the Ruling System and the Militias

The influence of militias in Iraq is directly tied to their political leverage and relationship with the ruling system, particularly those factions most loyal to Iran’s supreme leader. Many observers argue that Shiite alliances’ dominance in Parliament and their ability to form successive governments are heavily linked to their military strength. Armed groups have reportedly influenced elections through fraud in favor of Shiite alliances or by using the threat of violence to maintain their political control. This was evident in 2021 when militia fighters used weapons against Sadrist protesters in the Green Zone. The resulting crisis led to the withdrawal of Sadrist MPs from Parliament and Muqtada al-Sadr’s announcement of his political retirement, clearing the way for the Coordination Framework to form the current government.

Against this backdrop, Iraq’s prime minister faces a highly delicate balancing act, akin to walking a tightrope. He seeks to maintain good relations with the US administration to avoid sanctions or policies that could worsen Iraq’s crises. At the same time, he cannot afford to alienate the militias, as their existence underpins the strength of the Shiite-dominated political order that brought him to power. Furthermore, he fears that increased pressure on the militias could lead to large-scale unrest or violent escalation. Unlike in Syria, where many foreign fighters withdrew after the government’s collapse, Iraq’s militias are composed of Iraqi nationals, making the stakes even higher. Additionally, Iran, as Iraq’s direct neighbor, can provide immediate support to its allied militias in any confrontation that arises.

An Alternative Perspective to Resolving the Issue of Armed Actors

The challenges outlined above highlight the shortcomings of current approaches to addressing violent actors in Iraq. These proposed solutions often rely on unrealistic assumptions and fail to grasp the complex logic that governs militias. As a result, they focus primarily on a military response — such as the partial or complete dissolution of uncontrolled armed groups — while overlooking the political, economic, cultural, ideological and social dimensions that have shaped Iraq’s militia landscape for the past two decades. A more effective strategy requires drawing lessons from regional and international experiences with violent non-state actors while recognizing the unique complexities of the Iraqi situation. Given the urgency of seizing the current historical opportunity to establish the state’s monopoly on arms, an alternative “constructive and realistic approach” could be developed from an Arab perspective. This approach must be rooted in a deep understanding of Iraq’s militia dynamics and should aim — albeit in a limited capacity — to gradually transition from a militia-dominated system to a state-centered framework. Achieving this would necessitate progress along multiple, parallel paths.

Obliterating Auxiliary Armies

One of the key solutions emphasized in the literature on violent non-state actors is the elimination of auxiliary armies — not only in Iraq but also in Syria, Lebanon, Sudan and other regions. The PMF in Iraq exemplify such an auxiliary army because, although integrated into the armed forces, it retains the capacity to operate independently at any time. This structural ambiguity was codified in the PMF Law, Article 1, Second Paragraph 1, which states: “The Popular Mobilization shall be an independent military formation and part of the Iraqi armed forces, and shall be linked to the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces.”[16]

Other regional actors have recognized this issue in similar contexts. The Syrian administration has rejected demands from the SDF to be integrated as a unified entity, and the Sudanese army foresaw this challenge in relation to the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Given this precedent, proposed strategies for addressing violent actors in Iraq should shift their focus. Instead of framing the issue as dissolving uncontrolled armed militias, whether partially or completely, the primary objective should be framed as “dissolving the PMF.”

The core problem lies in how the PMF has been structured as an entity separate from the army and police, rather than in the existence of uncontrolled militias alone. The dissolution of militias should be accompanied by the transfer of their weapons to the state. This position aligns with the statement made by Shiite politician and Secretary-General of the Iraqi Loyalty Movement Adnan al-Zurfi during an interview on Dijlah satellite channel on March 3, 2025, where he described this process as a national duty and a prerequisite for genuine change toward building a new Iraq based on state-centric governance. This shift also corresponds with broader regional and international efforts to eliminate non-state actors. A recent example is PKK, whose opposition factions have accepted the call of their imprisoned leader in Türkiye Abdullah Öcalan to lay down arms after four decades of conflict. This decision, based on an agreed-upon executive mechanism, serves as a model for structured demobilization efforts.

Screening and Integration

The army must adopt strict controls prior to the integration process. These controls are based on screening and sifting between ideologically motivated elements, regular fighters and fighters with key roles in the PMF and militias, according to state principles. These elements must be redefined within the traditions of the Iraqi army, then excluded from the ranks of ideologically motivated elements and fighters with key roles, possibly retiring them or replacing them with civilian jobs. Their numbers are usually small, while regular fighters are integrated and absorbed into the army.

Individual Distribution

National military committees are formed to individually reintegrate regular fighters into units, divisions, battalions and brigades, according to army regulations and laws regarding military ranks, while taking into account national standards and avoiding sectarian bias.

Monitoring and Doctrine

Integrating elements into the army are monitored, and their commitment to the national military doctrine and their cohesion with the armed forces are monitored. Those proven to adhere to ideological slogans are excluded as what happened in previous years was the unregulated merging of militias and the PMF into the army, leading to the fragmentation of loyalties within military institutions and the emergence of the PMF as a complete, parallel entity.

Army Powers

The army’s powers to control the country must be activated by redeploying its personnel to strategic areas previously controlled by unruly PMF brigades and militias, such as strategic commodity areas, border areas and international highways.

Geographic and Demographic Distribution

In terms of deployment, fighters must be kept away from geographical and demographic incubators, in governorates other than their birth governorate and governorates other than their sectarian affiliation.

Reshuffling the Current Political Equation

The Iraqi case presents a far more intricate challenge than Syria and Sudan when it comes to dissolving auxiliary armies like the PMF. Unlike in Syria and Sudan, where violent non-state actors lack deep political entrenchment, militia logic dominates Iraq’s power structure, making dissolution efforts significantly more difficult. In Syria, the SDF do not have strong political representation in the government or Parliament, making it easier for Damascus to sideline or eliminate them. Similarly, in Sudan, the RSF, while militarily influential, do not enjoy the same level of institutional integration or parliamentary presence as the PMF. In Iraq, however, PMF-affiliated politicians and factions play a key role in the government and Parliament, making any move to dissolve the entity a direct political confrontation with entrenched interests. Achieving a national consensus on dismantling the PMF is difficult due to the deep entrenchment of the militia mindset within Iraq’s ruling system. The ruling regime, the Coordination Framework, the PMF and various militias are all key players in Iraq’s political landscape, while Iran, as an indirect but powerful actor, has a vested interest in preserving the PMF as a tool of influence. Given these complexities, many analysts argue that reshaping Iraq’s political landscape is necessary before any serious attempt to dissolve the PMF can take place. This requires shifting the political discourse away from a sectarian-militia-based security framework toward a state-centered national security strategy while encouraging narratives that promote the Iraqi state’s exclusive monopoly on arms rather than normalizing armed non-state actors. This could happen as follows:

There are influential political, economic and judicial militia figures who shape the Iraqi political equation, making the dissolution of the PMF a complex task at multiple levels. Many observers argue that pressure must be intensified, and additional sanctions should be imposed on political and military militia figures. The Trump administration may resort to freezing their assets and salaries or even threaten targeted operations against them, similar to the approach used to eliminate Hezbollah leaders in Lebanon. Reports indicate that several targeted militia leaders have already left Iraq, fearing assassination,[17] following repeated US warnings emphasizing the urgency of resolving the militia issue.

As Iraq approaches parliamentary elections in 2025, pressure should also be exerted on influential Shiite factions that, with Iranian backing, have historically bypassed the constitutional rule of forming a government through the largest parliamentary bloc.[18] Instead, they have relied on consensus to appoint Iran-aligned figures as prime minister. Iraq’s political system must be reoriented toward adherence to constitutional principles, providing space for figures and movements that transcend sectarian and national divisions, including civil and Sunni movements operating within different frameworks. The failure of Shiite political forces to build Iraq — and before it, Iran — demonstrates that the militia approach is inherently doomed to failure, whereas a national approach is essential for state-building and development. In contrast, civil-oriented movements — such as those that emerged after the Tishreen protests, cross-sectarian Shiite groups as well as Sunni and Kurdish factions seeking state-building —should be supported to assume a more significant role. This would help curb the dominance of Shiite alliances that perpetuate militia influence over state institutions.

Bringing Into Force Constitutional and Legal Frameworks

Dismantling the PMF

Article 9, Paragraph b of the Iraqi Constitution explicitly prohibits the formation of militias beyond the framework of the armed forces,[19] defining the legitimate armed forces as the army, navy, air force, air defense and border guards, all of which fall under the Ministry of Defense and the command of the prime minister as commander-in-chief. In comparison, the Sudani government’s program includes a provision to end the presence of weapons outside state institutions.[20] The PMF, originally established as a militia force, fundamentally contradicts the Iraqi Constitution and government plans. The justification for forming such militias — first to resist the US occupation and later to combat ISIS — is no longer valid, as the United States has significantly reduced its presence since 2011, and the primary military confrontation with ISIS has concluded. Consequently, there is no legal or practical basis for maintaining the PMF as an independent, armed entity.

Confronting Militia Headquarters

The Iraqi government is constitutionally obligated to confront terrorist militia headquarters. Article 7, Section 2, mandates combating terrorism in all its forms and preventing Iraq from becoming a base, corridor or operational arena for terrorist activities. Article 1 further prohibits any entity that promotes racism, terrorism, excommunication, sectarian cleansing or extremist ideologies.[21]

Protecting Neighboring Countries

Similarly, Iraq must uphold Article 8 of the Constitution, which emphasizes the principles of good neighborliness and non-interference in the internal affairs of other nations. This makes the presence of militias that entered Syria to support the Assad regime or threaten neighboring countries a clear legal and constitutional violation.

Confining to the Rule Giving Precedence to the Biggest Parliamentary Bloc

Adherence to the constitutional rule of the largest parliamentary bloc must be reinforced. Article 76 obliges the president of the republic to assign the prime ministerial nomination to the candidate from the largest parliamentary bloc.[22] Strengthening the role of the Federal Supreme Court in monitoring constitutional violations is also essential to ensuring its independence from militia influence.

Abolishing the Sectarian and Exclusionary Law

Addressing sectarian and exclusionary laws passed under the influence of the Coordination Framework is critical. Parliament has enacted legislation that enforces a Shiite identity, such as the Eid al-Ghadir Law and the Civil Status Law, which impose a Shiite narrative on Iraq’s diverse sectarian and ethnic fabric. Civil movements must be supported to halt the passage of such laws and to review existing legislation with sectarian undertones. In this context, repealing the Accountability and Justice act, which has been used to marginalize Sunnis by equating them with Baathism, is crucial to preventing further social and political alienation.

Consulting Arab Neighbors When Laying Out Approaches

The effectiveness of any strategy for dealing with armed actors in Iraq depends on the involvement of Iraq’s Arab neighbors in shaping its formulation and articulating their positions and perspectives. These countries possess the deepest understanding of the militia mentality in Iraq, making their proposals essential to enhancing the strategy’s effectiveness. This is particularly relevant given that Western capitals have come to recognize the validity of the approaches advocated by influential Arab and Gulf states in addressing the threats posed by Iran’s geopolitical project and proxy militias, both within affected countries and along international transit corridors. The heavy costs incurred by the West due to its previous disregard for these Arab perspectives now compel it to take their views seriously and engage with neighboring countries in developing a more effective approach.

The Prospects of Dissolving the PMF and Reintegrating It Into the Army

The PMF’s vulnerabilities can be leveraged to facilitate the process of dissolution and integration. These include:

The Constitutional Breaches Involving the Formation of the PMF

There has been widespread controversy in Iraq over the constitutionality of the law mandating the PMF to join the army since its passage in Parliament in 2016. This debate is particularly significant given that the PMF was formed from militias established in violation of Article 9 of the Constitution. Sheikh Thaer al-Bayati reiterated this in December 2024, stating that the PMF violates the Constitution as it consists of militias that were unlawfully established and that the majority of its brigades maintain affiliations with militias.[23] Furthermore, the PMF has not been individually integrated into the armed forces and enjoys a special budget estimated at $2.8 billion,[24] deducted from the Ministry of Defense’s total budget of $21.6 billion, despite being directly under its command.

In addition, many militias with brigades in the PMF are also listed as terrorist organizations by the United States, including Kata’ib Hezbollah, Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba and Sayyid al-Shuhada. Additionally, the involvement of many of their leaders in politics — whether by running in parliamentary elections or forming political alliances — violates constitutional rules that prohibit members of the armed forces from participating in elections or leading political parties. The head of the PMF, for instance, also leads the Ataa Movement, while figures from Kata’ib Hezbollah, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq and the Badr Organization are part of the Coordination Framework. Moreover, many militias operating under the PMF umbrella have been implicated in the killing of demonstrators and in extorting both citizens and foreign investment companies without facing accountability. Some PMF factions openly maintain ties to Iran and consider themselves an integral part of what Iran calls the “Axis of Resistance” which has recently endured unprecedented setbacks.

Najaf’s Support for State Institutions

Unlike Qom, the Najaf religious authority supports the state’s monopoly on arms, the consolidation of state authority and the independence of its decisions. This issue remains a key point of contention between the two religious authorities. As pressures on Iraq mounted, Najaf reiterated in November 2024 its demand for the state to maintain exclusive control over weapons, considering it a fundamental condition for building a new and stable Iraq.[25] Observers saw this as an urgent message to the government regarding the need to address the unchecked proliferation of weapons and a warning to militias to refrain from bombing US and Israeli targets to prevent Iraq from being drawn into renewed conflicts.

The Najaf religious authority argues that the rationale for militia formation has expired, in line with Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani’s 2014 fatwa on “sufficient jihad.” Accordingly, at the end of 2020, it decided to withdraw the Shrine Units — which pledge allegiance to it — from the PMF. These brigades include the Abbas Combat Division, the Imam Ali Combat Division, the Ansar al-Marjaya Brigade and the Ali al-Akbar Brigade. This move angered militias loyal to the PMF as it undermined their efforts to solidify the PMF as a parallel army.

Many observers suggest that Najaf is now expected to issue a fatwa dissolving the PMF, just as it once issued a fatwa that led to its creation. They note that the two visits of UN representative for Iraq Mohammed al-Hassan to Najaf were reportedly undertaken to request such a fatwa. However, Sistani’s refusal to meet with Hassan during his second visit was widely interpreted as a rejection of the request. It appears that Najaf prefers to avoid issuing a fatwa that could reignite sectarian conflicts and instability in Iraq. Nevertheless, based on its established positions, any government decision to dissolve the PMF would likely receive its approval.

The Dilemma of Governance and Politics Within Society

The challenges facing Shiites in governance, politics and society provide a critical opportunity to push for the dissolution of the PMF, which has lost key pillars supporting its existence as a formal military entity.

The Weakness of Iraq’s Political System — A Major Factor

Over two decades, the ruling regime — aligned with the PMF — has failed to build a stable Iraq, lacking national programs and a unified identity to address crises. Instead, it has relied on sectarian policies that serve Shiite sub-identity and align with Iranian interests, narrowing Iraq’s state vision. Corruption is rampant, exemplified by the “$2.5 billion theft of the century”* and failures in electricity, employment, and water infrastructure. Judicial inaction against corruption deters foreign investment, exacerbates poverty and fuels displacement, deepening Iraq’s governance crisis and undermining its political institutions.

A divided Shiite House

The Shiite political landscape is experiencing a deep crisis between factions that support and shape the PMF. The primary conflict is between two major Shiite alliances. The first is the Sadrist Movement, which advocates for a state-controlled system where all weapons are under government authority, rejects Qom’s influence over Iraqi decision-making, seeks to replace consensus-based governance with a nationalist approach, and promotes balanced foreign relations. The second alliance, the Coordination Framework, includes Iran-aligned factions like Maliki’s State of Law Coalition and Hadi al-Amiri’s Fatah Alliance. It supports the continued presence of uncontrolled weapons. Militarily, internal divisions exist among major militias loyal to Qom, such as Kata’ib Hezbollah, Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba, Sayyid al-Shuhada, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq and the Badr Organization. These conflicts revolve around PMF leadership, financial control over key areas, and border revenues, exacerbated by the deaths of Qassem Soleimani and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis.

The Ruling Regime’s Failure to Govern

This has led to a decline in its Shiite and popular support, particularly in the Shiite-majority southern governorates. As a result, Shiite, Sunni, and Kurdish public opinion has increasingly rejected sectarian rule, viewing it as serving an Iranian rather than an Iraqi agenda.

Dwindling Sectarian Base

This shift has been evident in several ways. Large-scale youth-led protests have emerged, driven by contemporary ideas that oppose sectarian entrenchment, ideological control and the dominance of clerical leadership. Additionally, pro-Iran alliances suffered major setbacks in the 2018 and 2021 parliamentary elections, as voters refrained from supporting them while favoring alliances advocating for state sovereignty. These developments highlight the growing strength of a broad popular movement that rejects the prevailing militia-dominated order in Iraq.

Iran’s Diminishing Militia Patronage Amid Fears Over the Ruling Establishment’s Survival

Iran, the main sponsor of the PMF, is experiencing an unprecedented period of weakness due to a series of regional setbacks in Syria and Lebanon. Hezbollah has suffered significant losses in both leadership and capabilities, forcing its withdrawal from the conflict and leading to a ceasefire under UN Resolution 1701.

Meanwhile, Iran’s ally, the Syrian regime, has collapsed, giving way to a new government that rejects ties with Tehran and is backed by Türkiye and Saudi Arabia — two dominant regional powers. Additionally, Iran now faces a new regional deterrence framework that has put it on the defensive amid mounting US pressure and Israeli threats. These developments have left Iranian leaders increasingly concerned about a potential repeat of the Syrian scenario within Iran itself, raising fears that the possibility of the establishment’s downfall is no longer unthinkable.

These Iranian setbacks have weakened Tehran’s ability to pressure the Baghdad government on the issue of dissolving the PMF. This comes at a time when regional developments have created a “Sunni sphere” surrounding Iraq, wary of the potential domino effect. This sphere includes Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Syria, and Türkiye — all of which support Iraq’s transition to a fully sovereign state and reject the dominance of militias.

Additionally, there is a growing regional and international consensus favoring Sunni governance over Shiite rule. This shift is evident in the West’s diplomatic engagement with Damascus after Sunni opposition forces gained influence in Syria. Even Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan, during his visit to Syria, noted receiving positive signals from the West about strengthening ties with the new Syrian leadership,[26] alongside the previous US administration’s move to ease sanctions on Syria before leaving office.

The Trump Administration’s New Stance on Violent Actors in Iraq

In his previous administration, Trump adopted a highly confrontational stance toward violent actors in Iraq, driven by their repeated attacks on US targets as part of Iran’s strategy to counter Washington’s maximum pressure campaign. This approach culminated in the assassination of Qassem Soleimani, the former commander of the Quds Force and architect of Iran’s regional influence, along with Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, deputy head of the Iran-backed PMF. Moreover, the Trump administration imposed sanctions on militias and their leaders to cut off their financial resources and designated some of their figures as terrorists.

In Trump’s second term, key figures in his administration have signaled an even more aggressive US stance toward militias. Vice President J.D. Vance, a former US Marine who served during the Iraq invasion, has maintained a strong anti-militia position, shaped by his military background and unwavering support for Israel. Similarly, Secretary of State Marco Rubio is known for his hardline approach to militias in the Arab region. He has been a vocal critic of the Biden administration’s handling of the issue, arguing that it has emboldened militias to undermine the security of strategic US allies in the Middle East. Rubio also contends that these groups have imposed significant economic burdens on Washington by necessitating additional measures to protect its partners. Like Vance, he is a staunch supporter of Israel.

A harsher stance against the PMF in Iraq is anticipated, especially as the United States has recognized the threat they pose to its interests. European governments have also grown increasingly aware of the security risks posed by Iran’s military support for Russia in its war with Ukraine. This has contributed to a broader regional and international shift toward dismantling violent non-state actors.

Dismantling the PMF – A Mission Beset by Multiple Challenges

Strengths of PMF and the Militias

The PMF and its militias hold considerable weight and influence within Iraq’s Shiite ruling system, enabling them to impact both internal and external power dynamics. Several factors contribute to their resilience against dissolution efforts:

- Strong ideological and sectarian cohesion among PMF brigades.

- Promotion of their role in combating ISIS in Sunni-majority areas.

- Consensus among Shiite alliances on the PMF’s legal and sectarian legitimacy.

- Robust backing from influential political alliances in Iraq.

- Significant Iranian financial and military support, though reduced in recent years due to sanctions.

- Independent funding sources from black market activities, extortion, and control over oil-rich areas and border crossings.

- The absence of a fatwa from the Najaf religious authority calling for their dissolution, unlike the fatwa that led to their formation.

- Iraq’s economic importance to Iran as a means of circumventing sanctions, particularly in light of the United States reinstating its maximum pressure policy against Iran.

Many sources have indicated that the three militias targeted for dissolution* have outright rejected any attempts to disband them. On January 20, 2025, the head of the Political Bureau of Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba, Ali al-Asadi, stated that the movement would not lay down its arms and dismissed the remarks by the head of the Hikma Movement Ammar al-Hakim regarding the threat posed by the resistance’s weapons to Iraq’s economy as mere early election propaganda.[27] Firas al-Yasser, a member of the Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba Political Bureau, also asserted that the withdrawal of US forces must precede any discussion of militia dissolution. Similarly, the spokesman for Sayyid al-Shuhada Kazim al-Fartousi argued that it is unrealistic for one’s adversary to expect them to disarm. Naturally, calls for dissolution contradict the militias’ private interests and the gains they have accumulated over the years, including their status, influence, power and financial benefits. As a result, an organized political campaign is likely to be launched against Prime Minister Sudani to weaken his chances of securing a second term.

A division may emerge among the leaders of the Coordination Framework regarding the dissolution of the militias, as not all factions share the same stance on the issue. Those groups closer to the prime minister tend to be more supportive of dissolution than others.

The Official Narrative Focusing on Dissolving the Militias, Not the PMF

The official narrative focuses on “dissolving the unruly militias” rather than “dissolving the PMF.” On December 22, 2024, Sudani clearly and explicitly affirmed his government’s categorical rejection of any external dictates or pressures seeking to dissolve the PMF, considering it an official body that was integrated into the army with parliamentary approval.[28] Observers link this official narrative to the government’s affiliation with the Coordination Framework, the main sponsor of the prevailing militia mindset in Iraq. They view it as an attempt to circumvent US pressures and avoid dragging Iraq into exhausting conflicts while simultaneously serving the interests of Iran and its militias by providing them with legal cover to remain within the PMF.

The government is making strenuous efforts to achieve two goals: first, to halt militia attacks on US and Israeli targets, and second, to persuade the unruly militias to accept the solution. As part of these efforts, Sudani met with the leaders of the Coordination Framework and the militias to discuss the surrender of weapons to the army. He then visited Tehran in January 2025, on a mission to convince Tehran’s decision-makers of the need to support the government in disbanding the militias to spare the country the consequences of US and Israeli retaliation. Khamenei’s emphasis during his meeting with Sudani that the “disbandment of the PMF” falls within Iran’s red lines may indicate his awareness of the danger to Iran’s influence in Iraq. His failure to discuss the issue of a “partial or complete disbandment of the militias” implies acceptance of their continued existence. However, Sudani’s meeting with the leaders of the Coordination Framework and his visit to Iran reflect his awareness that the key to a solution lies in disarming the militias.

In this context, Iraqi Foreign Minister Fuad Hussein stated in an interview with Asharq Al-Awsat on January 18, 2025, that Sudani informed the Iranians that the issue of dissolving the militias was an internal matter. He explained that the government was considering various approaches to address the situation of the factions, including surrendering their weapons and transitioning to political activity, integrating into the ranks of the PMF,[29] or withdrawing completely from the political and military scene. On January 21, 2025, Sudani reiterated that his government was working to integrate the armed factions within legal and institutional frameworks to build a new Iraq based on its cultural heritage.[30] This indicates a move toward at least a partial dissolution of the militias.

The Coordination Framework’s Veto Against Dissolving Militias

The rejection of the Coordination Framework,* which includes the most prominent political alliances loyal to Iran, to dissolve the PMF remains one of the biggest challenges to any potential dissolution efforts. This is because the Coordination Framework played a central role in forming the Iraqi government, and the PMF serves as its strongest tool for exerting influence over Iraq’s political landscape.

All Coordination Framework leaders consider the PMF a red line that cannot be compromised, citing religious, legal, and security justifications. These include the fatwa from the religious authority that led to its formation, parliamentary approval of its integration into the army, and its role in combating ISIS. This stance was reaffirmed by Issam al-Kriti,[31] a leader in the Coordination Framework, and Saad al-Saadi of the Fatah Alliance on January 21, 2025, with the latter emphasizing that no fatwa has been issued to dismantle the PMF, unlike the fatwa that originally sanctioned its establishment over a decade ago.

The leaders of the Coordination Framework are actively working to legally entrench the PMF and prevent the retirement of approximately 4,000 PMF members who have reached the retirement age of 60. This effort includes senior figures such as PMF Chairman Faleh al-Fayyadh, Chief of Staff Abu Fadak al-Muhammadawi and Security Chief Abu Zainab al-Lami. Leveraging their parliamentary majority ahead of the upcoming elections, they aim to pass a law that addresses perceived legal loopholes in the PMF law. A draft amendment — yet to be approved — proposes:

- Raising the PMF retirement age to 70 years.

- Allowing for the replacement of retired, removed, or dismissed members with new recruits at the same job level to maintain the PMF’s numbers and prevent its gradual decline.

This proposed amendment has sparked significant controversy, as it contradicts the Iraqi constitution, which sets the retirement age at 60. Many political forces have opposed it in Parliament. A potential compromise under discussion is the inclusion of a provision granting the prime minister the authority to extend the retirement age for PMF commanders and officials by an additional five years until suitable replacements are found.[32]

In return, the Coordination Framework may accept the partial or complete dissolution of the unruly militias. Its leaders are currently engaged in negotiations with the three militias targeted for dissolution, urging them to surrender their weapons.

Izzat al-Shabandar, a former member of Parliament and a politician with close ties to both the government and the militias, revealed that Coordination Framework leaders have agreed on the necessity of dissolving these militias and that the decision has already been made. He also noted that understandings between Sudani and militia leaders are progressing.[33] This aligns with statements from Wael al-Rikabi, a member of the State of Law Coalition, who suggested that all armed factions are preparing to hand over their weapons to the government.[34] The move aims to prevent devastating strikes on militia positions and the targeted elimination of their leaders, similar to what happened with Hezbollah in Lebanon.

However, some key figures within the Coordination Framework, such as Maliki and Amiri, are pressuring the government to push for an end to the US presence in Iraq.[35] This strategy serves as a bargaining chip to convince the militias to disarm.

Sadrist-Coordination Framework Concordance

Despite the stark contrast between the Sadrist Movement and the Coordination Framework regarding the nature of the state — with the former adhering to a state-centric approach and the latter favoring a non-state model — both Shiite alliances share common ground on the legal status of the PMF and its central role in Iraq’s political landscape. This alignment is partly due to the fact that Sadr himself controls three brigades within the PMF.

Therefore, when Sadr speaks about the state’s goal of monopolizing weapons, he specifically refers to dissolving the unruly militias. This stance is not new; on November 18, 2021, he called on parliamentary election-winning alliances with militias to disband them.[36] A day later, on November 19, 2021, he announced the dissolution of the Promised Day Brigade, an elite unit of the Mahdi Army (Saraya al-Salam),* as a symbolic gesture to encourage Coordination Framework-affiliated alliances to follow suit.

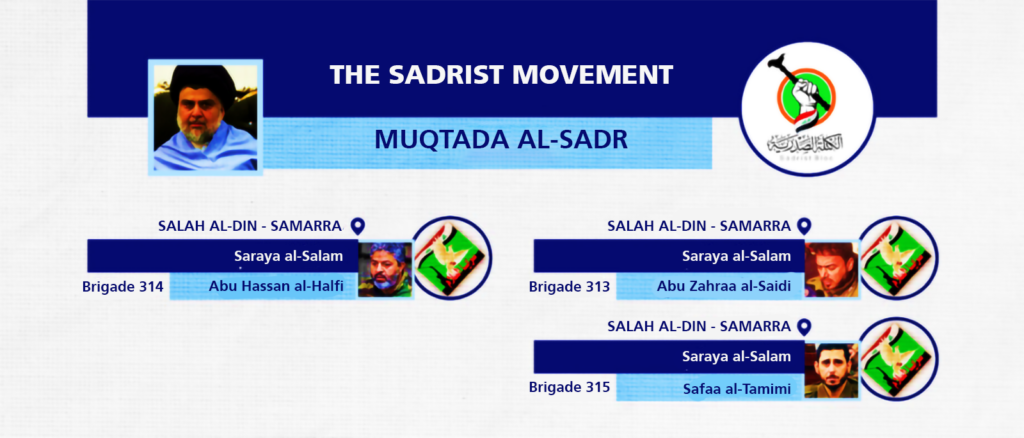

On January 6, 2025, following Israeli threats to strike Iraqi militias, Sadr reiterated his call to restrict weapons to the army.[37] However, a key question remains: Will Sadr take the step of dissolving the nine informal brigades affiliated with him? (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Sadrist Brigades Falling Under the PMF Umbrella

Source: https://bit.ly/3Ql61XM

Sectarian Dominance Over State Institutions in Iraq

Despite the Iraqi political system’s failure to resolve its crises, the continued dominance of Shiites over the executive, legislative and judicial institutions remains one of the key obstacles to dissolving the PMF. With their parliamentary majority, Shiite factions can block any legislation or legal measures aimed at dismantling the PMF.

Moreover, the government lacks the necessary leverage to enforce the dissolution of the PMF, given that it was formed by the Coordination Framework — the primary patron of both the PMF and various militias —with backing from Iran. The executive branch has no authority to hold militias accountable, and any confrontation with their leaders poses a significant risk. These armed factions openly assert their capacity to destabilize Iraq, making it perilous for Prime Minister Sudani to challenge them. His predecessor, Kadhimi, faced an assassination attempt when militias targeted his residence with explosives.

Shiite dominance over state institutions is a legacy of the sectarian quota system introduced by the United States after the 2003 invasion. This framework has enabled Shiite parties to control the government, Parliament and judiciary. As long as the quota system persists — excluding independents — Shiite factions retain control over more than half of ministerial portfolios, including sovereign ministries, while the remainder is divided among Sunnis, Kurds and minority groups.

Sectarian Incubators and Geography

Despite the decline in popular support for Iraq’s ruling Shiite establishment, the sectarian structure of the country continues to provide a strong base for the PMF and its affiliated militias. Shiites make up approximately 60% to 65% of Iraq’s population, with the majority adhering to the Twelver Shiite school of thought. This demographic reality serves as a strategic advantage for Iran, which views the Shiite population as a reliable support base for the PMF and its militias.

Furthermore, PMF brigades and militias are heavily concentrated in Iraq’s Shiite-majority southern provinces, including Najaf, Karbala, Dhi Qar, Basra, Babil, Wasit, Qadisiyah, Maysan and Muthanna (see Map 1). Several of these provinces — Basra, Maysan and Wasit — share borders with Iran, reinforcing Tehran’s influence and logistical access to these armed groups.

Map 1: Iraq’s Sectarian and Ethnic Distribution

Source: https://bit.ly/42W55k6

The Iranian Sponsor’s Geographical Proximity to Iraq

Unlike Syria, Lebanon and Yemen, Iran shares a 1,600-kilometer border with Iraq, featuring multiple crossings, including six official and five militia-controlled unofficial ones.[38] This border serves as a crucial channel for Iran’s influence in Iraq, facilitating illicit trade that strengthens its economic and military leverage. Through these routes, Iran swiftly supplies financial and military aid to the PMF and allied militias, while also enabling the movement of fighters amid US tensions. Tehran has actively pursued additional border crossings and railway links to deepen its connectivity with Iraq, though regional dynamics appear to have stalled these efforts.

Map 2: The Border Crossings Between Iraq and Iran

Source: https://n9.cl/u2h3q

Conclusion

The aforesaid suggests that proposed strategies for confronting violent actors in Iraq and shifting toward a state-centric approach diverge significantly from Iraq’s prevailing militia-driven logic. Such proposals could ultimately serve Iran’s efforts to deflect pressure on Iraq’s uncontrolled weapons and shift focus away from dissolving the Popular PMF, a core Iranian priority. The PMF functions as a parallel army to Iraq’s official military, boasting a larger force. If fighters from disbanded militias were absorbed into the PMF, its ranks would nearly double, further strengthening its influence over Iraq’s armed forces. This expansion would secure a larger budget, deepen control over the military’s leadership, and potentially enable the PMF to seize command of the army itself — an alarming prospect.

All Shiite factions, including the Sadrist Movement, unanimously oppose dissolving the PMF. Instead, they support, to varying degrees, the dismantling of independent militias as a tactical maneuver to appease American and Israeli legal, political and security demands while aligning with Iranian interests.

Dissolving the PMF hinges on an Iraqi-Iranian political consensus involving the government, Shiite alliances, and militias. Iran seeks to preserve the PMF as a parallel army akin to the IRGC, a vision articulated by Khamenei in his meeting with Sudanese officials. However, the United States wields several leverage points to compel Iraq and Iran into dissolving the PMF and integrating its fighters individually into the Iraqi army — aiming to establish Iraq’s independence from foreign influences.

The United States has multiple pressure tools, and the Trump administration had already begun removing Iraq’s exemption from Iran-related sanctions, jeopardizing its vital electricity imports. Other measures include:

Financial Sanctions

Washington could target Iraqi banks, oil firms, and financial systems to curb dollar smuggling. Of Iraq’s 44 official banks, 23 are already under US sanctions, with five more — Al-Mashreq, Al-Muttahid, Al-Amin, Misk, and Al-Sanam — potentially facing restrictions. This could destabilize the local dollar exchange rate, disrupt Iraq’s banking sector, and possibly extend sanctions to the state-owned oil company SOMO. The United States could also target PMF-linked militias, companies, and political or military figures while restricting PMF salaries, citing security concerns, as Adnan al-Zurfi suggested.

Oil Revenue Freezing

Since 2003, Iraq’s oil revenues have been deposited in an account at the US Federal Reserve, giving Washington significant control. In June 2023, the United States withheld $1 billion in Iraqi oil sales over allegations of illicit transfers to Iran, signaling its ability to restrict Iraq’s access to vital funds.

Military Leverage

Iraq remains dependent on the United States for weapons procurement and maintenance. Washington could block new arms deals, tying military aid to the dissolution of the PMF. Without US support, Iraq’s predominantly US-made arsenal — comprising about 80% of its weaponry — could deteriorate into obsolete “scrap” due to a lack of spare parts, maintenance and upgrades.

US Security Control Over the Al-Hawl and Al-Jad’ah Camps Along the Iraqi-Syrian Border

These camps, which hold thousands of ISIS members and their families from various nationalities, are supervised by the SDF with US support. If the United States were to withdraw, the camps would pose a significant security threat to Iraq’s already fragile stability.

The Critical Intelligence Iraq Receives From US Agencies

This is regarding terrorist plots, the locations of extremist operatives, and sleeper, tactical and active militant cells. Additionally, US air support remains vital for Iraq’s military operations against security threats.

The Potential Targeting of Lebanese Hezbollah leaders

This scenario could set a precedent for eliminating other militia leaders and key figures.

Beyond Iraq, the United States holds multiple pressure tools against Iran. The most impactful of these has already been enforced: the Trump administration’s maximum pressure campaign, which severely strained the Iranian economy and fueled mass protests against the government.

A second potential measure involves granting Israel the green light — either through direct support or tacit approval — to conduct preemptive strikes on Iranian military sites. This could extend to targeted assassinations of militia commanders and senior IRGC officers across Iran’s regional spheres of influence.

A third strategy would be to encourage European nations, many of which have suffered from Iran’s military backing of Moscow in the Russia- Ukraine war, to adopt more aggressive policies against Tehran.

The fourth and most decisive move would be pressuring for the disarmament of Lebanese Hezbollah. Analysts widely agree that forcing the Lebanese army to monopolize military power by dismantling Hezbollah would deliver a critical blow to Iran’s regional influence. This, in turn, would likely set a precedent for similar actions in Iraq —dismantling the PMF and affiliated militias.

Utilizing these levers, the US administration can exert pressure on all relevant parties to dismantle the PMF and associated militias. This could be accomplished by promoting gradual, non-violent, and systematic political, constitutional, and legal reforms, supporting fair constitutional elections, and backing a new generation of Sunni, Kurdish, civil and moderate Shiite political figures in Iraq. International oversight of upcoming parliamentary elections would be crucial, alongside the imposition of additional sanctions on political and military figures linked to militias. A scenario similar to that of Hezbollah in Lebanon could also be replicated, targeting influential Shiite and militia figures embedded within Iraq’s political system.

The trajectory of US pressure on Iraq’s armed factions remains uncertain, but if Washington refines its strategy and prioritizes these efforts, it could push for the PMF’s dissolution in a way that leaves little room for resistance. This could lead to severe economic sanctions on Iraq, potentially fracturing or even collapsing the Shiite political establishment. The United States might also sanction government ministers affiliated with the PMF and other militias, as well as Coordination Framework leaders, given their role in shaping government policies and their reliance on militia power to sustain the deep state. Military actions, including airstrikes on PMF positions, assassinations of militia leaders, or even a broader military intervention, could also be considered.

Several alternative approaches could accelerate the dismantling of the PMF. One option is for the United States to negotiate with Iran on the nuclear issue, offering sanctions relief in exchange for allowing Baghdad to move forward with dissolving the PMF. Another possibility is a “last resort” strategy — creating conditions that prompt Iraq’s religious leadership to issue a fatwa calling for the PMF’s dissolution. This would undermine the legitimacy of the militias’ continued existence. However, the key question remains: What mechanisms could be used to pressure the religious authority into issuing such a fatwa, especially given its concerns about triggering a broader conflict within Iraq?

A second anticipated scenario suggests that the Iraqi government may adopt a strategy of compromises and tactical maneuvers to avoid fully dissolving the PMF. This could involve dismantling select major militias that have been engaged in regional conflicts since Operation Al-Aqsa Flood or focusing on eliminating the most unruly factions. Additionally, Iran itself may play a role in shaping the PMF’s fate, as it faces internal challenges related to the presence of non-state armed actors within Iraq.

* Experts widely agree that a historic opportunity has emerged to dissolve the PMF before the outbreak of the regional conflict in Gaza, such a move was considered unrealistic — even discussions about dismantling unregulated militias seemed far-fetched. However, shifting regional dynamics have made what was once improbable a tangible possibility. Key factors influencing this shift include concerns within Iran’s ruling elite about the future of the ruling establishment, the vulnerability of Iran’s remaining militias following the heavy blows to Iranian proxies in Lebanon and Syria and mounting US and Israeli pressure on the Iraqi government to enforce state control over arms.

There are growing expectations that the new Trump administration will escalate its campaign against Iran and its affiliated militias in the Middle East as part of a broader strategy to weaken Tehran’s regional influence and impose a new deterrence framework. Many Iraqis view the dissolution of the PMF and other militias as a crucial step toward resolving the country’s complex crises.

Moreover, regional shifts further contribute to the diminishing role of violent non-state actors. A notable example is the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), whose opposition wing has responded to the call of its imprisoned leader Abdullah Öcalan to lay down arms after decades of conflict.

* The term “unruly armed militias” chiefly concerns to brigades and battalions that are not officially affiliated with the PMF (which was integrated into the state in 2016 as an auxiliary to the Iraqi armed forces). These militias engage in combat operations and military attacks, particularly against US and Israeli targets.

The general logic among Iraqi militias is that many major armed groups — such as the Badr Organization Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, Kata’ib Hezbollah, Saraya al-Salam, Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba and Sayyid al-Shuhada — have both officially recognized brigades within the PMF and additional brigades that operate outside its formal structure. The latter category consists of units whose numbers, locations and activities remain largely unknown.

These militias, often referred to as “uncontrolled militias,” reportedly number over 70 with many refusing to follow orders from the General Command of the Iraqi Armed Forces. Groups such as Kata’ib Hezbollah, Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq fall into this category. Additionally, numerous militias operate without even nominal affiliation with the PMF, making them even more difficult to regulate.

Shiite politician and former Najaf governor and parliamentarian Adnan al-Zurfi estimates that about 30% of these armed factions are under PMF control, while the remaining 70% operate independently, remaining infiltrated, unknown and engaged in covert activities.

[1] Jennifer Hansler, “Blinken Makes Unannounced Trip to Iraq as International Community Grapples With Syrian Regime Collapse,” CNN, December 13, 2024, accessed February 2, 2025, https://bit.ly/431f4o4.

[2] “US President-elect Trump Urged Iraqi PM al-Sudani to Reinforce State Control Over Weapons, Says Iraq’s Speaker,” Kurdistan24, December 30, 2024, accessed February 5, 2025, https://bit.ly/41bAQ6m.

[3] Official Website of the US Embassy in Baghdad, Post on X, February 25, 2025, accessed March 5, 2025, https://bit.ly/4buiPEJ.

[4] “Israeli Media Confirms ‘PMF Dissolution’ Intentions: U.S. Reassesses the Situation in Iraq – Urgent,” Baghdad Today, December 23, 2024, accessed February 3, 2025, https://bit.ly/3QpZds0. [Arabic].

[5] “Qaani Presents a Plan in Baghdad to Reorganize the Popular Mobilization Forces,” Al-Arab Newspaper, January 17, 2025, accessed February 3, 2025, https://bit.ly/3D0lIjX. [Arabic].

[6] “Khamenei: The PMF Must be Strengthened; the U.S. Seeks to Expand Its Influence,” VOA, January 10, 2025, accessed March 6, 2025, https://bit.ly/43sOogj. [Persian].

[7] “Chairman of the National Security Committee in Parliament: Dissolving the PMF Aligns With Strengthening Regional Terrorist Groups,” Mizan Online, January 15, 2025, accessed March 6, 2025, https://bit.ly/3Xts6aq. [Persian].

[8] The first attempt was during the first term of former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, after the sectarian conflict in Iraq ended with the establishment of a National Reconciliation Ministry aimed at resolving the conflict and integrating militias into the security forces. The second attempt occurred when the PMF was merged into the army despite the presence of many unruly militias. The third attempt came with US calls in 2017 to dissolve the PMF. Moreover, claims by militia leaders that the PMF is an official institution under the command of the prime minister, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces are not true. Since joining the army, these militias have not complied, as evidenced by their attacks on US targets, their repeated incursions into the Green Zone — the seat of state institutions — and, most notably, their threats against former Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi himself, under whose leadership they fall.

[9] Amir al-Kaabi and Michael Knights, “An Unusual Visit: The PMF’s Numbers in Figures,” Washington Institute, June 6, 2023, accessed February 1, 2025, https://bit.ly/41lnLID

[10] “Military and Security Service Personnel Strengths in Iraq,” The World Factbook, accessed February 2, 2025, https://bit.ly/3CSrLHn.

[11] “Iran-backed Iraqi Factions: Official Moves to Dissolve Them and Integrate Them Into the Military Institution,” Al-Rafidain News Encyclopedia, January 17, 2025, accessed January 5, 2025, https://bit.ly/4i6CNI6. [Arabic].

[12] Ibid.

[13] Hisham al-Hashemi, “Internal Disputes Within the PMF Authority,” Making Policies, July 1, 2020, accessed January 30, 2025, https://bit.ly/3ltjpbm. [Arabic].

[14] “The PMF: A Parallel Force to the Iraqi Army,” Dordou Media Foundation, January 7, 2025, accessed January 9, 2025, https://bit.ly/4b5UYep. [Arabic].

[15] John Davison and Ahmed Rasheed, “Exclusive: In Tactical Shift, Iran Grows a New, Loyal Elite from Among Iraqi Militias,” Reuters, May 21, 2021, accessed October 21, 2021, https://bit.ly/433cZIh.

[16] Official Website of the Iraqi Parliament, PMF Law, Article One, Clause 2.1, November 16, 2016, https://bit.ly/3D9PlPT.

[17] “Faction Leaders Depart for a European Country: Baghdad Faces a Final Opportunity,” Al-Alam Al-Jadid, December 12, 2024, accessed February 8, 2025, https://bit.ly/3EU65uR. [Arabic].

[18] Official Website of the Iraqi Presidency, Iraqi Constitution 2005, Article 7, accessed February 8, 2025, https://bit.ly/4gLLgiM.

[19] Official Website of the Iraqi Presidency, Iraqi Constitution 2005, Article 9, accessed February 8, 2025, https://bit.ly/4gLLgiM.

[20] Official Website of the Iraqi Government, The Ministerial Program of the Eighth Government Led by al-Sudani, accessed February 8, 2025, https://bit.ly/4gMbyl0.

[21] Official Website of the Iraqi Presidency, Iraqi Constitution 2005, Article 7.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Official Account of Sheikh Thaer al-Bayati, Post on X, December 29, 2024, accessed February 8, 2025, https://bit.ly/3QnH7Xq. [Arabic].

[24] Dordou Media Foundation, “The PMF: A Parallel Force to the Iraqi Army.”

[25] “Ayatollah Sistani Emphasizes Preventing Foreign Interference and Restricting Weapons to the State,” Iraqi News Agency, November 4, 2024, accessed February 5, 2025, https://bit.ly/4i5QK8U. [Arabic].