Rising popular discontent could provoke the rise of a new political establishment in several European states and at the European Parliament level in 2024. Two main drivers seem to be the underlying force explaining this political evolution: firstly, the fear of a new wave of migration and, secondly, the high level of inflation in Europe since the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine war in February 2022. This combination of social and economic factors constitutes the key explanation behind the rise of far-right parties throughout Europe. Their growth is fuelled by migration crises and the loss of purchasing power. This political development is also reflected in the in the policies of several governments within the EU. Indeed, while the ideological separation with the classical right-wing parties is withering away, parties belonging to the radical right could be the main beneficiaries of the European elections in June 2024. In more than half of the European countries, far-right parties now represent the second political force, which places them at the gates of power. In France, the National Rally (RN) even tops the polls for the next European elections. The far right is part of the ruling coalitions in Sweden, Finland and Latvia. And for a year, a post-fascist party has ruled Italy. The reasons for the success of right-wing populists are the same in France as in Germany, but also in Italy and Spain: it is the fear of economic and social decline.

Compared to emerging countries, Europe no longer appears as the center of the world, or as a continent capable of asserting its values. At the same time, domestically, European states are no longer able to offer a model of guaranteed prosperity. Nationalist parties recruit mainly from the losers of globalization who are not only people whose jobs have been lost, but also those who find that the changes in cultural references are happening too quickly. This includes part of the European middle class. The phenomenon affects countries from old Europe as well as states from Eastern Europe.

At the beginning of the 1980s, the electoral rise of the National Front, the former name of the RN, created in 1972, made France an exception in Europe. We know that this is no longer the case and that in many European countries not only do far-right parties now obtain scores comparable to those of the RN and sometimes higher, but also European electoral systems allow them to perform better than the French far-right. For the French far-right, the objective remains the same as in the previous election: to transform the European elections into a mid-term election, the result of which will structure the 2027 French presidential election when President Emmanuel Macron will finish his second mandate and will not be able to be a candidate for a third one.

The rise of the French RN is taking place in a fruitful political context: from Italy to the Scandinavian countries and Germany, the far right is gaining electoral ground by trying to use the fear of a new wave of migration from outside Europe to attract new voters. This political phenomenon is happening at a time when European authorities are weakened by the rise of a post-Western world order, which exacerbates the need for protection, hence heightening the sense of economic nationalism. Across Europe, there is a growing number of coalition agreements paving the way to power for far-right parties. This is the end of a political taboo in Europe: the entente between right-wing and far-right parties to form governments or parliamentary majorities.

The far right is also likely to make gains, particularly in Austria, with the possibility of entering the government after the September 2024 election, potentially as the largest party. According to the latest surveys, the European Parliament’s right-wing Identity and Democracy (ID) group could gain as many as 11 seats in the June 2024 vote. This radical right includes anti-system, national-conservative, identity-based and libertarian parties. All are riding on the promise of protecting their nationals against real or supposed threats.

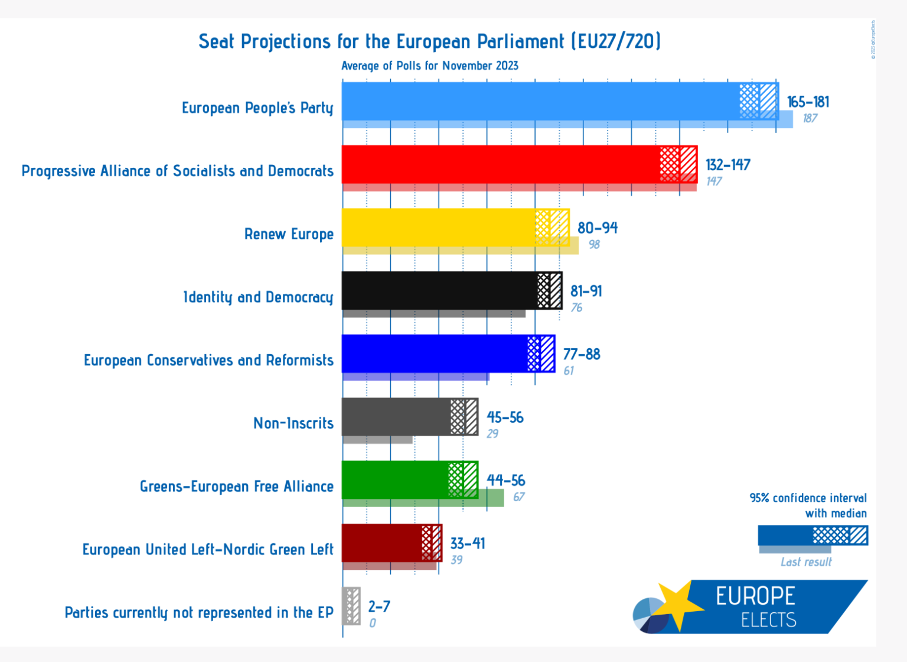

In the European Parliament, the various elected representatives of radical right parties are divided into two main groups: on the one hand, the ID, which notably includes the RN and the Italian League, and on the other, the European Conservatives and Reformists Group. Overall, radical right elected officials could increase from 130 to 180 seats in the future European Parliament after the elections in June 2024. This rise of far-right parties could influence the EU’s policy stance on issues such as immigration, climate change and EU enlargement. Finally, beyond the confirmation of this political phenomenon, one must consider the fact that far-right European parties are now part of the mainstream political discourse in Europe with a focus on identity-based issues and an economic discourse that takes into consideration the interests of European citizens who perceive themselves as the losers of globalization.

Source: Europe Elects.