Iran’s currency hit a new record low against foreign currencies, with one US dollar reaching as high as 21,000 tomans. The currency tumbled a few days after the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) Board of Governors passed a resolution on June 19, 2020, calling on Tehran to fully cooperate with the agency and to stop denying it access to suspected former nuclear sites.

Both President Hassan Rouhani and Governor of the Central Bank of Iran Abdul Nasser Hemmati said that the slump in Iran’s toman will be “temporary” and “balance must return to the exchange market.”

The following points will discuss the volatility in Iran’s foreign exchange markets in light of the current economic and international conditions, the implications of the decline of Iran’s currency on the Iranian government and people, and the possible options for the Iranian government to deal with the current crisis.

I. US Dollar Gains Value Against Iranian Toman and Iran’s Desperate Attempts to Support Its Currency

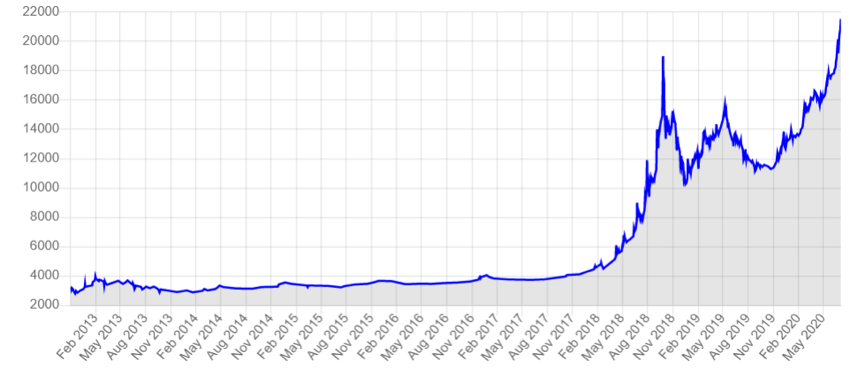

In April 2018, one month before the US withdrawal from the nuclear accord, the US dollar was valued at less than 5,000 tomans in the free market. Soon after the United States withdrew from the nuclear agreement in May 2018 and reimposed sanctions on Iran, the Iranian currency rapidly plummeted. In early July 2020, it fell to as low as 21,000 tomans against the US dollar. When compared to April 2018, the exchange rate of the toman fell by 320 percent and when compared to 2012, it fell by 600 percent.

Currently, the widely used free exchange rate is five times higher than the official exchange rate. The latter is set by the Iranian government at 4,200 tomans to a dollar for the purpose of importing essential commodities such as food and medicine.

Therefore, the currency crisis is set to cause further pain for the Iranian government and people alike.

Figure 1: The exchange rate of the dollar against the toman in the free market (2013-2020)

Source: Bonbast.com

On July 28, 2018, one US dollar accounted for 10,000 tomans for the first time. The exchange rate continued to soar until September 26 of the same year when one dollar was equal to 19,000 tomans.

To support their country’s local currency, Iran’s government and Revolutionary Guards pumped millions of dollars into the foreign exchange market, causing a slight fall of the toman exchange rate to less than 10,000 tomans. It is likely that the devaluation scenario will repeat itself and that the current toman exchange rate will deteriorate further. The Iranian government may temporarily inject dollars into the market during the next days or weeks to help reduce both the exchange rate and the public’s frustration.

The Governor of the Central Bank of Iran Abdul Nasser Hemmati’s description of the national currency’s fall as “temporary” is inaccurate. In December 2019, Hemmati made similar remarks when the exchange rate of the toman amounted to 13,000 per dollar but his remarks were proven to be false as he failed to fulfil his promise.

Even if Iran’s Central Bank, with the help of key players such as the Revolutionary Guards, decide to pump millions of dollars into the foreign exchange market, as their previous attempts show, they will face two daunting obstacles in their path to stem the recent exchange rate’s depreciation: the excessive domestic demand for the dollar and the external pressures imposed on the Iranian economy. Therefore, the Iranian government, whose budget is under severe strain as it supports the import of basic commodities such as food and medicine at a price of 4,200 tomans per dollar, will only be able to provide limited support.

II. Economic Pressures and Psychological Factors

The recent sharp decline of the toman’s value impacts Iranians psychologically. As Iranians have lost confidence in their local currency, many Iranians keep their savings in foreign currencies.

By attracting the people’s savings to the stock exchange market, the government in Iran is trying to curb cash in the hands of Iranians and control the high inflation rates. Recently, “justice shares” have been offered by the Iranian government to enable its citizens to buy shares in state-owned firms at low prices. The government’s move intends to reduce the purchase or acquisition of US dollars and this resulted in the stock market rebounding in the past three weeks. Nevertheless, Iranian small and large investors appear to prefer to use the dollar and euro instead of the toman, increasing the demand for the two currencies during times of fluctuating exchange rates.

Iranians have become accustomed to economic vicissitudes during any crisis between their country and global powers or organizations. Thus, they rushed to withdraw their savings to buy foreign currencies following the IAEA’s warning to Iran. Other reasons for the rapid fall of Iran’s currency include the harsh economic sanctions imposed on Iran for two years and the economic impact of the outbreak of the coronavirus in the country. These two factors have contributed to reducing Iran’s foreign currency revenues from its oil and gas exports as well as its non-oil trade with neighboring countries and tourism income.

Iran’s First Vice-President Eshaq Jahangiri acknowledged that there has been a sharp drop in the country’s oil revenues from $100 billion annually in 2011 to $8 billion during the last Iranian year.

The Economist Intelligence Unit forecasts that Iran will face an approximate $7 billion trade deficit in 2020 and a budget deficit of almost 9 percent along with high rates of unemployment and inflation. According to the International Monetary Fund’s estimates, Iran’s foreign exchange reserves will drop to nearly $70 billion.

III. Iran’s Options to Mitigate the Economic Pressure

Under immense popular pressure, Tehran has been trying to stop the currency depreciation; an exceedingly difficult goal in light of US sanctions on Iran and the effects of the coronavirus pandemic.

The Iranian government can only reduce, rather than eliminate, the effects of the economic crisis through the following measures:

A. Looking for New Financial Resources and Recovering Overdue Receivables

An example of Iran’s overdue receivables is the unpaid oil bills for fear of US sanctions and the debts owed to it.According to the Iranian government, Iran’s oil dues are estimated to range from approximately $100 billion to $130 billion, including about $9 billion owed by South Korea to Iran. In June, Tehran urged Seoul to release the oil-export revenues, however, South Korea chose to abide by US sanctions, sparking a dispute between the two countries.

In Iran, however, the government managed to force exporters to convert their foreign exchange earnings to the local currency and threatened to publicize the names of violators in the media and to stop providing importers with foreign currencies.

The Iranian government also resorted to the old plan of “justice shares” which was issued in 2006. To fill the empty coffers of the state, the Iranian government aims to sell the shares of a basket of 49 state-owned firms on the stock exchange at attractive prices to citizens. The firms’ total value is estimated at 369.5 trillion tomans (approximately $88 billion at the official rate).

B. Using Iraq as a Corridor to Import Supplies

Tehran plans to get around US sanctions, particularly the oil embargo. Therefore, the country may be planning to export Iranian goods stamped with “Made in Iraq” labels in return for fees paid to Iraq or relief from Iraq’s overdue debt burden to Iran, estimated at $8 billion, for importing gas and electricity from Iran over the past two years. Iran plans to export non-oil goods worth $41 billion by the end of the Iranian year, or an equivalent amount has been set for targeted imports to reduce domestic demand for the dollar. Iran will most likely fail to achieve such a goal amid the current economic circumstances and the spread of coronavirus, except with considerable assistance from neighboring Iraq. For this reason, the Governor of the Central Bank of Iran Abdul Nasser Hemmati made a visit on June 17 to Iraq where he met the Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kazemi who confirmed his country’s support for Iran.

C. Creating a Fait Accompli Situation and Betting on the Time Factor

This strategy entails Tehran enduring the negative economic consequences of the currency devaluation in order to pursue its current foreign policy and external schemes, which puts it at odds with the international community, at least until the US election is concluded in five months.

This strategy was reflected in the remarks of the Governor of the Central Bank of Iran Abdul Nasser Hemmati. “Whatever is going on in the foreign exchange market is short-lived and we are not going to change our monetary policy just because of transient shocks,” Hemmati said during an interview with Iranian state television on Monday evening, June 22, 2020.

The currency depreciation in Iran is a direct result of the country’s policies which Iran thinks the people should endure so that the country can realize its ideological ambitions and foreign policy objectives.

Iranians, along with the currency crisis, will have to bear other significant economic costs, such as:

- Higher costs of raw materials and imported intermediate goods needed for production.

- Higher inflation rates and higher costs of imported goods.

- The decline of purchasing power among Iranians in general and the poor in particular and the middle class.

- Class inequality.

- Increased prices and demand for residential property and gold by investors. According to Iranian statistics, rents increased by 30 percent to 50 percent in June on an annual basis, while the inflation rate of basic commodities reached 60 percent.

Conclusion

The toman has hit a historic low against the US dollar, as the dollar was offered for as much as 21,000 tomans. Yet, the Iranian currency may see a slight increase due to the government’s efforts to support the local currency and to reduce the public’s frustration. Amid deteriorating economic conditions and Iran’s differences with the international community, Iran’s local currency will most likely suffer a further depreciation.

In July 2018, the toman’s rate declined to 10,000 against the US dollar for the first time. Since July, the Iranian currency continued to depreciate until it recorded its lowest ever rate in June, adding to the burden on low and middle-income citizens. The Iranian government will look for a way out of its financial crisis with minimal losses. The options available for Iran include the sale of state-owned firms under the “justice shares“ plan, the use of Iraq as a safe conduit, betting on the time factor, and waiting out the US presidential elections scheduled for November 2020.