Introduction

Following World War II and the Cold War, the United States declared itself the greatest victor. It spearheaded the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in order to establish a new political reality in Europe that would serve its interests and expanded the alliance to accomplish more aims and leverage itself further in the international spheres, particularly in Europe. The United States sought to provide justifications to keep in place its military bases in Europe while undermining France’s and Germany’s political moves to minimize US influence over Europe. Simultaneously, the United States attempted to isolate Russia from Europe and thwart any economic, political or military integration or rapprochement attempts between them. Furthermore, the United States allowed the Eastern European countries to join the alliance in order to remove them from Russia’s orbit. The United States’ aim behind this move was to prevent Moscow’s reemergence as a rival power and to maintain its position as the world’s sole hegemonic power.

Superpowers have always sought a foe throughout history; they deliberately create one if they cannot find one. The existence of a nemesis appears to be the key to a nation’s survival and progress. Courtiers without a formidable enemy will decline, retreat and vanish. Without a foe, a country will lack the political and popular justifications for entrenching power and expanding influence. It will also be unable to mobilize people to support political leaderships or justify foreign interventions. The September 11 attacks provided Washington with a pretext to invade Afghanistan and occupy the country for the next 20 years. Furthermore, the United States invaded Iraq based on the false accusation that the country possessed weapons of mass destruction. In Europe, the United States recognizes that NATO’s existence is dependent on the presence of a major geopolitical foe. For more than seven decades, the alliance protected Europe from the threat posed by the former Soviet Union. Once the Soviet Union collapsed, the geopolitical threat disappeared. As a result, NATO’s main raison d’être ended, and its purpose became unclear. French President Emmanuel Macron declared in 2019 that NATO was experiencing “brain death.”

The world is used to the fact that Europe only awakens during times of crisis and convulsions and most likely, it lacks preemptive strategies against potential threats. Europe crafts new strategies and arrangements to address crises but when they end, all newly pursued security and defense arrangements revert back to square one.

At present, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has forced the Europeans to restructure their security system and think about a host of new strategic plans/initiatives. But many Europeans are pondering over the future of this European geopolitical/strategic leap after the Russian invasion of Ukraine ends. Can the EU truly adopt the French “European strategic autonomy” initiative or has the Russian invasion resurrected and revitalized NATO once again, providing reasons for the alliance’s existence and Europe’s continued military dependence on the United States?

NATO: A Guarantor of European Security Against Russia

Following World War II, Washington was convinced that its next foe would be the Soviet Union, which had triumphed against Nazi Germany. The United States quickly realized that it needed to establish new rules for the next geostrategic game in Europe, where most of the battles against Nazi Germany took place. Stalin believed that Russia must be surrounded by countries that were not allied with the United States. Over a period of nearly five decades, the Soviet Union did not establish a modern state nor did it provide economic welfare or grant freedom. It eventually collapsed, along with the Eastern European countries that had always spun in its orbit. They moved closer to Europe and NATO in their quest for social welfare, democratic governance and military protection from any prospective Russian aggression.

The Geostrategic Expansion of NATO Toward Encircling Russia

The context that led to NATO’s creation has changed. The Soviet Union no longer exists, the bipolar world order collapsed, the Cold War finished, the European Union (EU) was institutionalized further, and China has emerged as a formidable power in the international arena. However, despite these shifts and changes, Russia has remained as the West’s sworn foe and NATO has been expanding eastwards.

When the alliance was formed in 1949, it only had 12 members: the United States, the UK, Canada, Belgium, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, and Portugal. In 1952, Greece and Turkey joined the alliance, three years before West Germany. In 1982, Spain became a NATO member, bringing the total number of members to 16. After the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact, the Eastern European countries — once part of Soviet bloc — began to join NATO. Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic joined the alliance in 1999. In 2004, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia and Bulgaria joined NATO. In the same year, the three Baltic countries (Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia) — that are in direct geographical contact with Russia — joined the alliance. In 2009, Albania and Croatia joined the alliance. Montenegro joined NATO in 2017. North Macedonia was the 30th and the last country to join the alliance in 2020.[1] NATO has continued to bolster its military capabilities, incentivize the military activities of its member countries, further expand, and establish military bases near the Russian borders, with Moscow viewing this as a national security threat.

Nonetheless, it is important to note that before Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula in 2014, NATO did not have any plans to deploy combat troops in its eastern European member countries. The Russian invasion of Crimea — added to Moscow’s invasion of Georgia in 2008 — was indicative of a new phase of tensions with Russia. In the face of Putin’s desire to increase Russia’s Lebensraum (living space) by expanding toward Eastern Europe, NATO began to strengthen its military presence in this part of Europe to deter Moscow and secure the security of its eastern European allies. For example, during the NATO Summit in 2016 held in Warsaw — in response to concerns about Russian advancements toward the alliance’s eastern European member countries, and after Moscow had taken control over the Crimean Peninsula — the leaders of the NATO member countries agreed to enhance the deployment of the alliance’s Forward Presence battlegroups in eastern and southeastern Europe.

Enhancing NATO’s Forward Presence in Eastern and Southeastern Europe

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, NATO agreed to create four multinational combat groups. This Forward Presence of the alliance was first created in 2017, with multinational battalion-size battlegroups formed in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland on a rotational basis. Then, additional combat reinforcements were deployed to Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia — rotationally led by the UK, Germany, and the United States. The battlegroups are strong, and ready to act in case a NATO member country is attacked; an attack on one member country is akin to an attack against the entire alliance. This brings the total number of multinational battlegroups to eight, extending throughout the eastern part of the alliance — from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Black Sea in the south. Meanwhile, the alliance’s member countries continue to contribute additional forces and military capabilities at all levels (ground, air, and sea) in the Black Sea region.[2]

Furthermore, land units in the southeast of the alliance were deployed around a multinational brigade, under the Multinational Division Southeast in Romania. At sea, NATO deployed more ships and conducted more naval exercises. In the air, the alliance intensified its training, which contributed to improved situational awareness and enhanced readiness.[3]

Since the start of March 2022, NATO member countries have sent warships, warplanes and additional troops to eastern and southeastern Europe, which has enhanced the alliance’s deterrence and defense posture. This included sending thousands of additional troops to the alliance’s battlegroups and fighter jets to support aerial patrols as well as reinforcements in the Baltic Sea and the Mediterranean (see Figure 1). Despite declining confidence in NATO in recent years, especially among European quarters, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has contributed to breathing new life into the alliance. The invasion has forced NATO to adjust and develop new initiatives/strategies in light of Moscow’s aggression and threats.

Figure 1: The Distribution of NATO Forces in Eastern and Southeastern Europe After March 2022

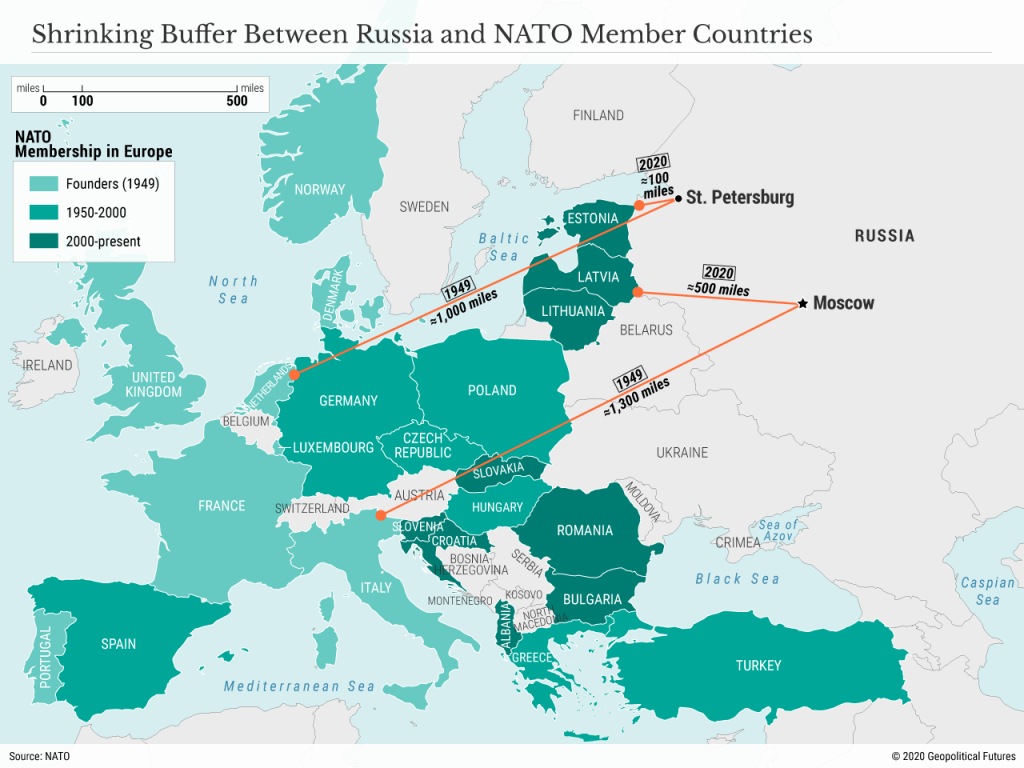

For the European countries to decisively beat Russia, they need to capture Moscow. But the Russian capital is a long distance off, and any successful move against it will require the deployment of much military power and forward supply lines. While advancing on Russia, military capacities/power will significantly diminish. Both Napoleon and Hitler arrived in Moscow exhausted because of the long distance and bitter cold. In light of the aforementioned, NATO seeks to preemptively reposition itself near Russia’s borders so that Russian cities fall within its firing range. During the climax of the Cold War, the Russian city of Saint Petersburg was 1,000 miles away from NATO forces and Moscow was 1,300 miles away. Today, Saint Petersburg is only 100 miles away and Moscow is nearly 500 miles away (see Figure 2). Putin believes that NATO and the West in general have become a direct threat to Russian national security.

Figure 2: The Shrinking Buffer Between Russia and NATO Member Countries

The Deployment of Ballistic Missile Defense Systems Terrify Moscow

In 2002, the United States withdrew from the landmark 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, citing the need to develop a global missile defense system to defend against what it called “rogue states:” Iran and North Korea. This justification did not convince Russia and it believed that Washington intended to edge its missile systems closer to its borders, hence preemptive action must be taken to stop this threat to Russian security.

The US-led missile defense doctrine is based on establishing military bases and deploying missiles and defense systems on land and at sea to prevent any intercontinental missile from targeting it or its allies. The United States has established many military bases while others are under construction. The United States’ missile defense systems identify/track the locations of hostile missile launching pads and destroy them once launched. These missile defense systems intend to deter countries from developing and using ballistic missiles against US and Western interests. In addition, they aim to undermine Russia’s deterrence capabilities in the territories it views as its Lebensraum.[6]

Among the largest US military bases in Eastern Europe are six bases in Poland where 5,500 US troops are deployed. Washington also canceled plans to establish a military base in the Czech Republic. In these two countries close to Russia’s borders, the United States has deployed two of its most effective missile defense systems that are capable of intercepting attacking missiles: Aegis Ashore and Thaad. In 2016, the United States announced it would establish a military base in Romania costing $800 million. The aim was to enhance its missile deterrence and to work with NATO forces in Romania.[7]

In 2018, Poland signed a $4.75 billion deal with Lockheed Martin and Raytheon to procure Patriot PAC-3 systems and complementary radars. The first batch will consist of two Patriot missile batteries, each with 16 launchers and PAC-3 missiles. The delivery of these systems to Poland is expected to begin in 2022, according to international press reports. The Patriot’s first unit will be deployed in the field in 2024. After Russia began deploying Iskander missiles in Kaliningrad, this deal was signed. According to Foreign Policy, the Russian army deployed Iskander missiles to the front lines on the border with Ukraine. Iskander is considered the most potent and crucial missile system in the Russian military. It is part of Russia’s new “Iron Curtain” to defend its borders against any prospective aggression. These missiles are thought to be among the fastest in the 21st century. The goal is to shoot down the enemy’s jets and missiles. They have a 500-kilometer range.[8]

In fact, before the Ukrainian conflict, Europe was concerned about the Iskander missiles. Following the Russians’ use of the Iskander missiles against Ukraine, Kyiv was terrified. The New York Times reported that “American intelligence officials discovered that the barrage of ballistic missiles Russia has fired into Ukraine contains a surprise: decoys that trick air-defense radars and fool heat-seeking missiles. The devices are each about a foot long, shaped like a dart and white with an orange tail, according to an American intelligence official. They are released by the Iskander-M short-range ballistic missiles that Russia is firing from mobile launchers across the border when the missile senses that it has been targeted by air defense systems.”[9] Perhaps this revelation explains why Ukrainian air defense systems had difficulty intercepting Russia’s Iskander missiles. Powered by a solid-fuel rocket motor, the Iskander can reach targets more than 200 miles away, according to US government documents. Each mobile launcher can fire two Iskander missiles before reloading.

In any case, Russia has improved its missile capabilities since learning that the United States intends to target strategic nuclear missile bases in its heartland, thus threatening its nuclear deterrence capability. As a result, it believes Poland’s participation in the United States’ missile defense project makes it a prime target for a nuclear missile response if conflict was to break out. Poland’s air defense has been evolving for several years amid growing concerns about Russia’s escalation.

Ukraine, on the other side, raises Moscow’s concerns. In 2014, Kyiv began modernizing its systems, increasing its missile stockpile, and developing medium and short-range missile systems. In 2015, Ukraine’s Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council Oleksandr Turchynov revealed the country’s intent to rebuild its missile shield, develop the Neptune cruise missile and the Vilkha and Harim-2 multiple rocket launch systems at tactical missile complexes. Ukraine’s Pivdenne Design Office is also working on another project, the subsonic cruise missile Hun-2. According to some Ukrainian military officials, the missile’s design will pit it against the US Tomahawk and Russia’s Calibr cruise missiles. There is no question that such developments in the field of missiles and the creation of a missile base in Ukraine have been a source of major concern for Moscow. [10] In 2019, the Ukrainian army was expected to receive upgraded missile systems such as the Buk, the S-300 and S-125. Prior to these expected arrivals, Ukraine’s airspace had been well protected by the S-300 PT, S-300PS, and BUK-M1 missile defense systems. According to the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense, efforts are underway to repair short-range air defense systems such as the OSA-AKM and Strela-10, as well as the Shilka self-propelled anti-aircraft missile system and the Tunguska air defense missile system, primarily to combat low-altitude targets such as drones. The ministry also announced that another promising advancement will be made in Ukraine’s Dnipro surface-to-air missile of middle range, which has a declared range of 650 kilometers.[11]

As a result, it came as no surprise that Russian missile attacks and airstrikes were designed to destroy the Ukrainian air defense system, its bases, and its air force’s infrastructure, which was rendered dysfunctional in a matter of days. Russia is aware that since Ukraine’s regime change in 2014, and its leaning toward the West, Ukraine has turned into a hotbed for NATO military bases — as is the case with Poland, the Czech Republic, Romania and the Baltic countries. Russia is fearful that its national security will be severely compromised. I believe that by invading Ukraine, Russia believes that it has succeeded in laying the groundwork for its preemptive approach which is in line with its greater Ukrainian strategy to counter the West’s clout and enhance its strategic depth in the former Soviet countries.

The EU Role on the Geopolitical Chessboard

The recent Ukraine-Russia crisis made the Europeans fully aware of the fact that energy and defense are the two primary sources of constant threat to Europe. The EU, therefore, should work to control and manage these two critical fields. Hence, it is not surprising that the EU Summit, held from March 10 to March 11 in France’s city of Versailles as part of its rotational presidency of the EU, focused on the independence of European energy and defense. Moreover, the coronavirus pandemic has forced the EU to acknowledge the strategic cost of depending on China. The Russian invasion of Ukraine obliges the EU to address the intermingling security and economic challenges it faces. It also necessitates the EU to use whatever tools are available to counter the new complicated set of challenges, both geopolitical and geo-economic.

New Tools Adopted by the EU

Some Europeans believe that the war in Ukraine is a wakeup call for the EU in order for it to act in a strategic way. In other words, it is better late than never for the EU. Through the European reaction to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it was apparent that the EU began to employ a comprehensive set of tools, starting from the harsh economic sanctions on Russia, activating its European Peace Facility and supplying Ukraine with weapons. Only one week after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the EU agreed to increase the package of economic sanctions on Russia. It is likely that this economic tool will be intensified over the coming years with the aim to deal a severe blow to the Kremlin’s energy sector. A host of European oil and gas companies, including Shell, BP and Equinor, have started a phased withdrawal of their investment operations in Russia.[12] As a coercive tool against Russia, it is clear that the EU is ready to take advantage of its full economic leverage. The United States and its European allies have discussed banning Russian oil and gas imports. Despite not reaching an agreement, the discussions per se reflect the fact that the EU is ready to face the cost of rising energy prices in order to secure political capital and weaken the Russian economy that has displayed resilience so far.

Internally, the EU has eased obstacles to allow Ukrainians to enter European territories. European policymakers in Brussels launched the Temporary Protection Directive, which was outlined in 2001, but never activated. This emergency measure grants protection to a large number of Ukrainian refugees through providing them with residency rights, access to the European labor market, medical care and education. In parallel, the EU moved to suspend Russian media outlets such as Russia Today and Sputnik. The European Commission’s East StratCom Task Force intensified its efforts to tackle Russian misinformation.[13]

More importantly, the EU has emerged as an influential security bloc on the geopolitical chessboard through activating the European Peace Facility. This instrument has been operational since July 1, 2021 to address the financial loopholes in the EU’s joint security and defense policy and support partner countries in the military and defense fields. This instrument will allocate €500 million worth of arms to Ukraine, including lethal weapons.[14] Not only has this geopolitical awakening taken place in Brussels, but after years of military hesitation, Germany dramatically shifted its defense policy through announcing a €100 billion special fund for defense spending over the next four years plus a permanent commitment to spend over 2 percent of GDP on defense.[15] In addition, Sweden declared that it would boost its defense spending, and Denmark has complied with NATO’s 2 percent GDP guideline on defense spending. Romania and Latvia seek to increase defense spending to reach 2.5 percent of GDP. Poland aims to raise defense spending to reach 3 percent of GDP in 2023.[16] The UK has also announced that it intends to carry out the biggest investment in its armed forces in three decades despite the coronavirus pandemic and its socioeconomic ramifications. This step is in line with the UK government’s efforts to restore the country’s standing on the global stage, especially post Brexit. In November 2020, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson pledged to increase defense spending by £16.5 billion to restore the UK’s global standing – according to him – to establish the leading naval force in Europe. The UK’s current annual defense budget stands at £42 billion.[17]

However, despite the European wakeup call regarding what is seen as an illegitimate war waged by Russia against Ukraine, the EU has only succeeded in employing some of the comprehensive tools available at its disposal. So far, it has not employed all its tools to impose vast geopolitical pressure on Russia by agreeing on a united defense and economic strategy, with all of the bloc’s member countries consenting to it.

Sustained Efforts to Win a Long-Term Strategic Game

As the policy of force is reinstated, the Europeans are now facing a new and long-term geopolitical game which necessitates that their efforts are ongoing, and not short-term. EU member states increasing their defense spending is an important starting point. There are those who hope that the aforementioned efforts translate into EU-level coordination. Accordingly, EU member states will benefit from the European Defense Fund to increase their defense budgets in a coordinated way. The comprehensive borrowing program to finance European defense will allow the EU to escalate against Russia in response to its growing threats. In case Russia threatens the stability of the Baltic countries or the northern EU member countries, ensuring European flexibility and overcoming EU institutional paralysis will be critical to tackling such threats.

It seems that the EU, instead of using its 27 member countries to defend Europe, will focus on employing Article 44 of the EU Treaty which assigns any security or defense mission to a host of European countries that have the capability or desire to take up the mission. To achieve this end, NATO and its partner countries could renew support for the EU battlegroups and the rapid response multinational military units created in 2003 that have not been used so far. [18]

The EU cannot play a long-term role on the geopolitical chessboard unless it redesigns its neighborhood policy with unanimous agreement among its member countries on the bloc’s roles and responsibilities. For years, the Balkan countries have been discussing ways to strengthen their relationship with the EU. However, inconclusive talks on this issue prompted these countries to seek alternative partnerships, particularly with Turkey, Russia, and China. Furthermore, the EU’s attempt to forge a friendship ring with the Balkan countries through the Eastern Partnership as an alternative to accession to the bloc was merely ink on paper. Perhaps there was some focus on aspects related to economics, fighting corruption, and culture. However, there was almost no focus on security or defense; both were set aside. Countries such as Georgia and Moldova are concerned about Russian aggression. However, Brussels has dismissed their concerns. Is the Ukrainian crisis teaching the EU a lesson that it should accelerate the accession of these countries in the coming years while also adding a security dimension to its neighborhood policy through instruments like the European Peace Facility?

This leads us to believe that the EU’s role on the geopolitical chessboard will be determined by its ability to integrate geopolitical economics with political geography. To prepare for a long-term geopolitical game, the EU must reconsider its economic-geographic position. According to the Directorate-General for Energy, the EU is the world’s largest natural gas importer. Russia accounts for the lion’s share of European gas imports (41 percent).[19] Germany, in particular, has always maintained that Nord Stream 2, the gas pipeline which transports Russian gas via the Baltic, is a purely “economic” project with no “political” aim. The war in Ukraine eventually disproved Russia’s claim, forcing the Europeans to diversify their energy sources from the start of the conflict. But it is not that simple or quick. In the short term, European policymakers must prepare their people for rising energy prices. As a result, they must be prepared for heated discussions and debates at home with their voters, who will face the ramifications of the sanctions on Russia.

Given that the other gas-exporting countries, particularly those in the Gulf, have signed future contracts or are committed to OPEC policies, Europe will suffer until an alternative to Russian gas is found. Europe is also focusing on renewable energy sources, but the renewable sector is still unprepared for intermittent sources like wind and solar energy to completely compensate for the energy shortfall. Additionally, renewable energy sources have so far been unable to meet demand, which may force some European countries to return to coal, which will impact the EU’s climate change objectives.

The EU Summit in France held from March 10 to March 11, 2022, led to the Versailles Declaration, which reiterated the importance of enhancing the bloc’s defense capabilities, reducing dependence on Russian energy, and building a stronger economic base.[20] This declaration is a European acknowledgement that energy and political geography are inextricably linked. French President Emmanuel Macron is pushing for a joint financing plan to support energy supplies and strengthen the EU’s defense capabilities. Such a step may be risky, but it is the only option if the Europeans want to ensure that their efforts in line with Macron’s vision do not diminish after the current crisis ends because of budget constraints. If Macron is able to present a French-German proposal for intra-European borrowing to fund the development of European energy and defense dimensions, the EU’s ability to operate within the framework of political geography and economic geography will improve. But it remains uncertain whether the Macron initiative will lead to a European consensus. However, it is certain that it will remain a focal point in France’s European project, particularly after Macron’s election to a second presidential term.

Are We Seeing Real European Strategic Independence or Further Dependence on NATO?

The issue of European defense, since the establishment of the EU, has not been greatly discussed. It has achieved less consensus in public and political debates. Maybe the situation is different now. There is a stronger European need to have a joint military force in light of Brexit, and doubts over the United States’ commitment to the transatlantic relationship within the framework of NATO after Trump’s approach toward Europe.

Trump’s “America First” policy led him to threaten to pull the United States out of NATO; he had exerted pressure on NATO member counties to increase their financial contribution to the alliance. The Europeans will need to advance joint defense cooperation beyond the framework of NATO as long as they doubt the US commitment — in light of Washington’s changing administrations, policies and priorities. These European doubts are confirmed by some positions and policies embraced by the United States as well as some alliances it has established. It appears that the Anglo-Saxon bond is more significant when compared to the Euro-Atlantic bond — and sometimes the former comes at the expense of the latter. In the face of this European concern about NATO’s declining role and a weakening of the transatlantic partnership, France launched two strategic approximations. The first is the European Intervention Initiative (EII) and the second is the Strategic Independence Project.

The European Intervention Initiative

The EII is a new stepping stone in efforts toward European defense. Today, it translates into tangible and workable cooperation measures. The idea of the EII was first brought up in December 2017 by the French president. The objectives of the initiative, through developing a joint European strategic culture by the start of the next decade, include equipping Europe with a joint defense budget, a joint intervention force, and a joint doctrine to enable the continent to act together militarily in a convincing manner. Let us note here that one of the three aforementioned goals, a joint defense budget, is about to be met as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It was unclear whether this goal was to be met in December 2021. In light of this initiative, it appears that the European defense project is taking shape more clearly and is much more tangible than before. In fact, the initiative’s members have the will, despite the fact that their numbers are low, only 13 European countries out of 27 EU member countries. They do, however, have a genuine desire to forge strategic and military ties, as well as to boost their financial and human resources in order to respond rapidly and effectively to any potential threat.[21]

A total budget of €30 billion has been allocated for the initiative over seven years (2021-2027). It is likely that the budget will be divided into several items. A €13 billion European defense fund will be established dedicated to defense research in the coming seven years. The European Peace Facility, worth €10.5 billion, will be dedicated to financing the EU’s operations that have military and defense implications. Finally, there is a package of measures to enhance “military advancements” within the EU through the provision of an additional sum of €6 billion.[22]

As for the joint intervention force, there are several examples: the Combined Joint Expeditionary Force established by the Lancaster House Treaties in 2010; the joint UK, Baltic, Scandinavian, and Dutch expeditionary force established by another Lancaster House agreement in 2015 and completed in 2017; the German Framework Nations Concept (FNC) in 2014, which was established within the framework of NATO; and the Franco-German brigade currently deployed in Mali. The EUFOR Crisis Response Operation Core (CROC) is the most recent of these initiatives. It is a capacity-building project established under the umbrella of the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO). It was formed in November 2017 by 25 European countries, with the exception of the UK, Denmark, and Malta.[23]

CROC improves the crisis management capabilities of the EU through enhancing the bloc’s readiness to create forces and ensure that they are prepared. In addition, CROC ensures the commitment of EU member countries to participate in operations. A sufficient increase in ground force readiness can be achieved through a multinational brigade operating within the framework of CROC. Further, enhancing resilience at all levels is critical. Achieving set objectives through using CROC’s effective crisis response interoperability is likely to be much more probable than any other similar initiative.

Several advantages are anticipated from this initiative. First, it addresses the root cause of the problem: the significant differences between EU member countries, especially when it comes to identifying threats and the varying measures to guard against them. Despite recent developments, each country continues to evaluate positions from its own perspective, and each country has its own concerns and solutions. But this initiative will not be successful unless EU member countries carry out several steps, such as allowing their strategic visions to be examined/assessed, exchanging intelligence information, carrying out joint operational planning, developing a joint combat doctrine, and outlining unified administrative measures. It is also necessary to change the public mindset and establish joint rules regarding territorial clashes. Without such rules, the EU’s military operations will quickly deteriorate because of the limitations that each force has. Scenarios and joint exercises must also be developed to facilitate interoperability.

The second advantage of this initiative is that it operates outside of EU institutions via easily adaptable operational measures. This approach is highly practical: there are no admission criteria other than a simple invitation. There are no long-term commitments, penalties, or even assessments of effectiveness. The initiative consists of a group of countries that share a common vision of threats and a nearly unified defense philosophy.

Finally, because it operates specifically outside of EU parameters, this European initiative has the potential to include the UK despite its departure from the EU as well as Denmark which opted to withdraw from the Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP). At the same time, the initiative allows countries such as Sweden and Poland, which have long opposed strategic autonomy for fear of losing US protection, to participate.

Though the initiative seems appealing and has several advantages, it is difficult to make a final evaluation as its details are still under review. The number of participants is also small. Military cohesion among the forces participating in this initiative will continue to be a challenge. The problem with this initiative, in my opinion as a researcher, is that it is focused on responding to what some European countries, such as France, see as a threat to its interests in the Middle East and Africa, displaying the same old colonial mindset. It has paid no attention, knowingly or unknowingly, to potential threats to Europe, such as those from Russia, or to threats impacting EU internal security such as terrorism, drug trafficking, natural disasters, domestic violence and separatist conflicts. Therefore, after the Ukrainian crisis ends, Europeans may believe that it is logical and effective to support and join this initiative, while restricting its military activity to protecting the European continent from direct threats and not expanding beyond European borders.

Is the European Strategic Independence Project Still on the Table?

Before the Russian invasion, terms like sovereignty, strategic autonomy and strategic sovereignty emerged, particularly in French discourse. All of these terms reflect the same idea: “We as Europeans should work together and independently whenever possible.” In fact, the semantic debate between NATO supporters and proponents of strategic autonomy continues. Some European countries, particularly in Eastern Europe, believe that distancing from the United States is a curse, whereas others, particularly France, believe that Europe should consider giving more confidence to European institutions and support strategic autonomy, including the capacity to resist and respond at a military level.

The EU is already an economic and normative power (competition law, regulation, and compliance law; General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) and REACH, which is one of the most far-reaching and comprehensive pieces of environmental legislation issued by the EU), as well as a trading powerhouse. The EU has signed more than 50 trade treaties to date, compared to 18 by Japan and 14 by the United States, and it provides more than half of the world’s official development assistance. Moreover, it is an air and space powerhouse (Ariane, Airbus, Galileo/Copernicus).[24]

In my opinion, the EU’s problem is not economic, but it lacks a unified army or joint defense force. So far, the EU has failed to develop the infrastructure to safeguard its collective security. It also lacks a joint defense policy, and its military operations are small in comparison to those of NATO.

France has laid out the strategic autonomy project, which aims to transform the EU from a geopolitical powerhouse into an international geopolitical player in order to gradually achieve independence from the United States. This idea gained popularity in Europe, particularly during the term of US President Donald Trump (2017-2021), as growing European submission to the United States was not desired at the time, compared to President Obama’s tenure (2009-2017).

The problem lies in the conflicting interests of the European countries and each country focusing on their bilateral ties with Washington. This is a major obstacle to the European strategic autonomy project. There is another obstacle, which is that the EU, in its essence, is not a military bloc but rather a joint economic marketplace. In other words, it is the lack of political will rather than the lack of resources that prevents the EU from becoming an independent military force in the international arena. The EU member countries do not agree on a unified geopolitical vision nor on threats. Achieving European strategic autonomy hinges on the ability of French diplomats to convince their European allies that there should be a new European military organization alongside NATO. The project’s success is also contingent on approval from the United States. For political reasons, the Biden administration may agree to it. However, the Pentagon is likely to oppose it.[25]

For its part, Paris faced criticism because of its one-sided bilateral dialogue with Russia. During the period from 2019 to 2020, French President Emmanuel Macron invited the Russian President Vladimir Putin to start a dialogue with Russia without consulting key EU partners. This is one of the reasons why the Baltic or Eastern European countries do not support the French initiative for strategic autonomy. Additionally, in an interview with The Economist, Macron said that NATO was brain dead.[26]

This criticism of NATO harmed Macron’s credibility not only in the United States but also in most European countries. Following the pressures on France, it appears that the strategic autonomy project shifted its focus from creating an alternative to NATO, as desired by France from the outset, to supplementing the alliance rather than supplanting it.

French decision-makers are convinced that this pragmatism will help them persuade most EU member countries of the significance of the strategic autonomy project. Paris has always advocated for European sovereignty through the EU. But it at the same time has honored its commitments toward NATO through deploying its forces to Romania and Estonia. However, some European countries, which are likely to be harmed the most by Russia’s geographical expansion, Poland, the Baltic states and the Scandinavian countries, continue to turn to the United States and NATO as guarantors of security.

In the face of the Russian invasion, divergences have emerged between the EU’s eastern and western member countries. While Poland and the Baltic countries have reiterated the importance of NATO in countering the Russian danger, the rest of the European countries such as Germany, France and Hungary have opposed this orientation. French President Emanuel Macron categorically ruled out any NATO intervention in Ukraine or establishing a no-fly zone or any possibility of the alliance partaking in the war. Poland and Hungary are moving toward division in the European Council. Poland is exerting pressure to impose sanctions on Russian gas, oil and coal imports and for sending a NATO humanitarian mission to Ukraine. Hungary, along with Germany, are obstructing sanctions on Russian energy imports and are seeking to avoid any NATO embroilment. They fear sanctions on Russian energy imports will trigger a European recession.

In terms of defense, it appears that EU member countries are reviewing their defense policies and have realized that a deterrence force is needed in the future. Germany has expressed a desire to play a larger defense role in the aftermath of Russia’s attack on Ukraine, which clearly influenced Berlin’s decision-makers. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz announced a €100 billion special fund to enhance the country’s armed forces’ defense systems. “We will create a special fund for the German army to use for pumping investments in the defense field,” he told lawmakers. “It is clear that we must significantly increase investments in homeland security to ensure our freedom and democracy.” He advocated that the army’s fund should be enshrined in the German Constitution, while also calling for a rise in defense spending – more than 2 percent of total GDP, rather than the current 1.5 percent.[27] This indicates a long-term shift in Germany’s role in European defense and a sharp reversal of the military policy that Germany has pursued since the end of World War II.

Even if the immediate threat posed by Russia fades, the Europeans recognize that they cannot continue to operate in silos. Even European countries that are typically concerned about EU defense cooperation may reconsider their positions. Denmark, the most recent example, announced in July, 2021 that it will hold a referendum on whether to join the EU’s CSDP. Unless EU member countries agree to massive investments in the bloc’s defense, it appears likely that the Europeans will continue to coordinate and exchange efforts through the bloc while remaining aligned to NATO.

Indeed, the United States, Canada and Norway have already been invited to join the EU’s PESCO project on military mobility, which is expected to serve as a model for future cooperation. The United States is likely to play a significant role in the EU’s ability to become an independent geopolitical player: it is already pushing for the EU to become the geo-economic arm of transatlantic security cooperation. The EU’s geopolitical position will also be determined by the United States, in particular, Germany and Eastern Europe will await Washington’s green light before committing to intensive coordination within the EU. At the same time, the EU is likely to emerge as a more autonomous geopolitical representative following Washington’s chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan and the formation of the AUKUS alliance, as well as in light of the possible election of a Trump-like candidate in 2024. The aforementioned factors are likely to advance the initiative for European strategic autonomy. The Russian invasion of Ukraine also reflects the United States’ preference to empower and equip its European partners so that they are responsible for their own security rather than deploying direct external force. In this context, the United States has refused to establish a no-fly zone over Ukraine, but allows NATO member countries, including Poland, to deliver combat aircraft to the country.

Even after leaving the EU, the UK remains a key partner in European defense. Since the beginning of the European crisis, the UK has demonstrated its credibility as an ally through engaging in active dialogue with Russia and providing tangible support to Poland. In the face of the ongoing tensions on the Ukrainian border, the UK defense secretary reiterated that 350 Royal Marine troops would be deployed to Poland in the coming days to support the Polish armed forces through joint drills, emergency planning, and capacity building. This assistance is provided on a bilateral basis and is not part of the UK’s NATO offer.[28]

While an agreement on security cooperation between the EU and the UK remains out of the equation, bilateral defense cooperation remains a decisive operational tool in addressing the continent’s security challenges. Moreover, the UK is included in defense cooperation mechanisms with other European countries, such as in EII and Nordefco, which has five members: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. Its goal is to strengthen member countries’ defense capabilities by identifying areas of cooperation and promoting effective solutions.[29]

These small defense formulas can fuse into forming a European defense system that coordinates European efforts with NATO’s in accordance with a unified strategy. The Versailles Summit provided encouraging signs that this period of European awakening may result in enough European political will to strengthen the EU’s energy, autonomy and defense capabilities, allowing it to move away from complete dependence on the United States.

Conclusion

We are aware that the EU has made slow collective progress since its inception. Its progress was only fueled by the shock of crises, much like the GCC, which appears united only when faced with a specific crisis. All of the EU’s impressive achievements, from the second half of the 20th century to the present, have occurred during times of crisis, not peacetime. When everything is fine, each country rushes to defend its own interests and national visions. All EU-level collective decisions are contentious or take a long time to reach consensus.

Today, the EU is going through a critical juncture, which necessitates it to take major strategic decisions in case it wants to remain strong and cohesive. The first decision in the short run is reaching a unified European strategy that prevents Russia from absorbing Ukraine within its orbit and stopping Russia’s advancement toward other Eastern European countries.

The second decision in the medium and long run, from my point of view, is regarding the future of European military defense against current and future threats. Will Europe continue to fully depend on NATO for militarily defense? Or has Europe learnt the Russian lesson? Is it willing to accept the French initiative on strategic autonomy to start building its own joint defense force? Or will it be a bird flying with two wings, NATO’s and its own joint force?

In any case, it appears that the EU has entered a period of geopolitical transformation. In the coming months and years, the EU’s political leaders will be forced to engage in political debates, dialogues, and revisions of the bloc’s status quo/current situation in order to identify the approach that is most suited for the future. This approach will be critical in determining its position on the global stage, and its future fate. Perhaps several upcoming variables will help reawaken the old continent: the return of Russia as a geostrategic threat to the Eastern European countries, China’s rise and its imminent overtaking of the United States as the leading global economy, China’s economic penetration into Europe and the rapid growth of its hard power, the Turkey-Greece crisis (which has compromised the EU’s border arrangements ), and finding solutions for the current crisis through transatlantic cooperation has rendered clear the divergence of interests between the United States and Europe. The concept of European autonomy in the field of defense and energy will be the subject of political debate over the coming decade between European leaders within the context of their ongoing pursuit to find security alternatives to the United States as well as to find alternatives to Russian gas, which Moscow can use at any time to paralyze the European economy.

Finally, the reactions of European leaders to the current and future shocks will reveal to what extent the EU has the political and popular will to achieve its unity project; it has succeeded in this endeavor to a large extent. And now there are mounting calls by European voices that demand the EU now succeeds in developing a unified military vision too. The EU member countries realize that they cannot solely contain the looming threats or attempt to act individually as strong players in a multipolar world order which is taking shape in front of our eyes. They recognize that strengthening EU collectiveness is no longer an option, but rather a strategic necessity dictated by the need to overcome the current Ukrainian crisis and its economic and security ramifications, as well as to prepare for a future shrouded in uncertainty, volatility and chaos, not just in Europe, but throughout the world.

[1] “Mapped… This Is How NATO Forces Are Deployed in Eastern European Countries,” Al Arabiya, March 27, 2022, accessed March 31, 2022, https://bit.ly/36G3QL7. [Arabic].

[2] “NATO’s Military Presence in the East of the Alliance,” NATO, March 28, 2022, accessed April 3, 2022, https://bit.ly/3LUEkkr.

[3]Ibid.

[4] NATO, Twitter post, 12:45 pm., March 24, 2022, accessed March 31, 2022, https://bit.ly/3lYZKS8.

[5] “Russia’s Search for Strategic Depth,” GPF, November 17, 2020, accessed April 12, 2020, https://bit.ly/3xmuS4X.

[6] Dalal Mahmoud, “The Ukrainian Crisis: The Real Objectives of Russia and the United States,” The Egyptian Center for Thought and Strategic Studies, February 22, 2022, accessed March 21, 2022, https://bit.ly/3wnQpdb. [Arabic].

[7] “A Confrontation Between the American Missiles Defense and the Russian ‘Iskander.’ Which One Will Prevail?” Al-Jazeera, February 11, 2022, accessed April 17, 2022, https://bit.ly/3JNB2h5. [Arabic].

[8] “US Missile Defense in Eastern Europe,” Defense, September 2020, accessed April 13, 2022, https://bit.ly/3rj7Nwr.

[9] John Ismay, “Russia Deploys ‘Mystery’ Missiles Capable of Spoofing Air-Defense Radars,” The New York Times, March 14, 2022, accessed April 13, 2022, https://nyti.ms/3G5OsVG.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “Russia’s War on Ukraine: the EU’s Geopolitical Awakening,” GMF, March 8, 2022, accessed April 4 , 2022, https://bit.ly/3K6yMm1

[13] Ibid.

[14] “EU Adopts New Set of Measures to Respond to Russia’s Military Aggression Against Ukraine,” European Council, February 28, 2022, accessed April 10, 2022, https://bit.ly/37BCqpW

[15] “Germany’s Foreign Policy Took a Dramatic Turn on Sunday,” GMF, February 28 2022, accessed April 10 , 2022, https://bit.ly/3jpAYtb .

[16] “Russia’s War on Ukraine: the EU’s Geopolitical Awakening.”

[17] “Britain Announces the Largest Military Budget in 3 Decades,” Al Sharq, November 19, 2020, accessed: April 25, 2022, https://bit.ly/3EJzTGw

[18] “Russia’s War on Ukraine: the EU’s Geopolitical Awakening.”

[19] “Why Europe Is so Dependent on Russia for Natural Gas,” CNBC, February 24, 2022, accessed April 25, 2022, https://cnb.cx/3xQCvRz

[20] « Déclaration de Versailles, 10 et 11 Mars 2022, » Présidence Française du Conseil du L’Union Européenne, March 11, 2022, accessed April 10, 2022, https://bit.ly/3LXf5xR. [French].

[21] « L’Europe de la Défense à Travers l’Initiative Européenne d’Intervention (IEI), » Institut Talleyrand, March 23, 2021, accessed April 25, 2022, https://bit.ly/3LdO2Ox. [French].

[22] “The European Intervention Initiative: Why We Should Listen to German Chancellor Merkel,” IRIS, July 16, 2018, accessed April 25, 2022, https://bit.ly/37GQLSp

[23] Ibid.

[24] “European Sovereignty, Strategic Autonomy, Europe as a Power: What Reality for the European Bruno DUPRÉ Union and What Future?” Foundation Robert Schuman, January 25, 2022, accessed April 25, 2022, https://bit.ly/3v9b7MW

[25] “The Future of NATO and the European Strategic Autonomy Project,” Rasanah, November 3, 2021, accessed April 11, 2022, https://bit.ly/3jso25P

[26] Ibid.

[27] “How Did Putin Awaken ‘the European Sleeping Giant?’ Germany Strengthens Its Arsenal,” Sky News, February 27, 2022, accessed April 11, 2022, https://bit.ly/3E2AX8b. [Arabic].

[28] “Defense Secretary and Polish Counterpart Reaffirm Commitment to European Security,” GOV.UK, February 8, 2022, accessed April 11, 2022, https://bit.ly/3JA5QBP

[29] “Russia’s War on Ukraine: the EU’s Geopolitical Awakening.”