Introduction

Several major theoreticians and observers of the new dynamics in international interactions agree that given the recent global power shifts and revised foreign policy paradigms, the criteria for gauging the strength and standing of countries are no longer based on purely traditional standards as was the case in the past. This comes in light of the back-to-back global shifts impacting the current hierarchal structure of the global order as well as the standing of regional and global axes. New international criteria have significantly emerged, which present the world’s countries with different challenges as a result of the change in the concept and tools of power due to international developments. These criteria include a state’s location, its geopolitical advantages on the map of axes and global trade and logistical corridors, especially the corridors that facilitate transformations in global economic movement and maritime trade. There are, thus, potential impacts on a state’s standing and weight based on its position within strategic trade corridors.

Leaders of the G20, which include the most powerful and influential economies within the global economic structure that met in New Delhi on September 9 and September 10, 2023, are aware of these changes in the criteria of measuring a state’s power. In a remarkable development that could strengthen the standing of the parties to the group, including the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, on the map of global logistical axes and achieving interests based on the concept of partnership, Saudi Prime Minister and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman announced on the sidelines of the G20 meetings the launch of a massive transnational economic corridor linking India, the Middle East and Europe. The corridor, if accomplished, will change the status of global interconnection as we know it.

This study sheds light on the impact and significance of the proposed trade corridor, which is expected to be a strategic turning point on the map of global corridors. A number of observers concerned with international trade predict that the corridor — if established — will take international trade to a new crucial stage with positive impacts analogous to the revolutionary introduction of maritime canals. The monograph also puts forward methodological interpretations of the scope of opportunities, gains, implications and consequences for the economies of several countries — providing a host of political approximations to pave the way for benefiting from this project. The corridor is also expected to impact the positions of rivals concerned about the project’s future impacts, particularly given that the countries involved in the project are all heavyweights, stretching from Asia to Europe. Some of these countries are classified as emerging, promising and rising economies — while others are deemed as advanced industrialized economies —according to international criteria. The study concludes with measuring the gains in comparison to the obstacles in order to ascertain whether adopting such a massive project could bear fruit.

The Global Economic Corridor’s Features and Routes

Several countries, including India, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Jordan, Israel and the EU countries, signed a memorandum of understanding to establish the so-called India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), according to the White House’s official website.[1] The move comes out of an awareness of the potential gains and implications for the standing (of each of these nations) on the map of global logistical axes as well as the position within the global order’s hierarchy and the massive influence on the movement of global trade. The following lines summarize the project’s most salient features:

Relative Weight of Participating Countries

The majority of the countries located within the scope of the corridor are endowed with massive economic (be they emerging or advanced, industrialized economies), political (possessing tools of influence on both the regional and global arenas) and geopolitical (possessing geopolitical advantages by virtue of their geographical location) capabilities. And given their enormous capabilities and huge resources, these countries play prominent roles that influence global affairs. The global powers located within the corridor’s scope make up a route that extends thousands of kilometers and links to Asia, a region marked by overall stability.

The corridor branches off into two routes. The first is located eastwards, and starts with India, a rising economic power and one of the major buyers of oil from the Gulf states. The corridor links India to the Gulf region, an oil-rich region that is politically and economically rising on the global stage due to its massive economic resources as well as the awareness of Gulf leaders of such capabilities. The second part of the corridor heads northwards, connecting the Gulf states with the industrially, technologically and economically advanced nations in Europe. These nations are in urgent need of alternatives in light of the mounting consequences of the global shifts in the field of energy and other vital resources, particularly the impacts of the Russia-Ukraine war and the emergent transformations in Africa.

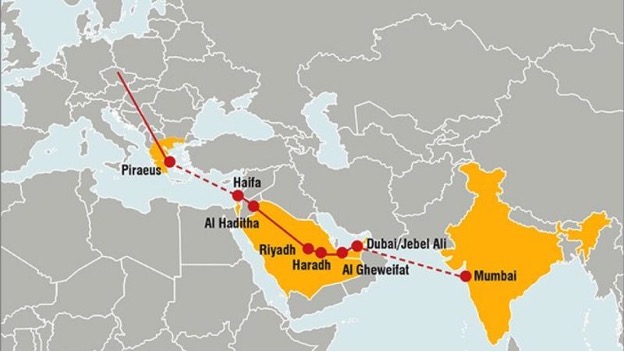

The economic route of the corridor begins by sea from India, which has a lengthy coastline that overlooks both the Indian Ocean and the Arabian Sea. Specifically, it runs from the port in Mumbai via the Arabian Sea and ends at Dubai Port in the UAE. The train line starts in the Gereida region of the UAE, continues through the Saudi territories, turns south toward Jordan, and ends in Haifa, Israel. The corridor’s course then resumes on the water, going from Haifa Port to Peraeus Port in Greece. Then, from Greece through the rest of Europe, the overland portion resumes.

Map 1: The Corridor’s Routes and Lines

Source: Euroactive.[2]

The Multiplicity of Routes and Lines of Interconnection

In comparison with other global corridors, whether already functioning, partially implemented or merely proposed, the intercontinental infrastructure (lines of interconnection) of the proposed corridor are multiple and various. The infrastructure goes beyond the notion of a single line, as is the case with multiple proposed international corridors, instead involving additional lines serving multiple purposes. Thus, the corridor includes the establishment of a pipeline for exporting clean hydrogen, electricity and digital communications cables and railroads in order to enhance global energy supplies. This will in turn lead to a qualitative transformation in terms of enhancing economic and trade ties among the parties to the project. This will also facilitate the swift transportation of commodities and individuals, create job opportunities and reduce gas emissions, thus helping to protecting the environment. Several countries located within the project’s scope have shared objectives with regard to this project, including Saudi Arabia, which seeks to become the world’s biggest producer of green hydrogen by 2026 by producing 1.2 million tons of green ammonia annually — 600 tons of green hydrogen per day — and exporting it to global markets.[3] This of course is in line with the Vision 2030 priorities.

The Ambitions of the Parties Involved With Regard to Implementing the Project

In comparison to other global corridors, the parties to the proposed corridor are unanimous in their desire to avail of the benefits presented by this project — due to considerations unique to each participant that has its own calculus as well as regional and global ambitions to bolster its standing. The indications of such ambitions abound. For example, the parties to the project have announced a clear agenda starting within 60 days from the project’s announcement to prepare a clear action plan to start preparing the project’s infrastructure. These indications include the clear Indian desire to get heavily involved in the policy of global corridors and to emerge as a global force with formidable influence on the map of global logistics, corresponding with its vision to economically ascend (the Indian Dream). In addition, the United States was conspicuous in its support of the project at the G20 summit, where US President Joe Biden described the project as historic. There is a Saudi desire to diversify supply lines and corridors and support global supply chains. This project is in harmony with the 2022 Saudi Global Supply Chain Resilience Initiative and the 2021 National Strategy for Transport and Logistics. These indications come within the framework of the Saudi strategy of economic diversification in light of the Vision 2030 targets. Moreover, Saudi Arabia has the capacity to honor its commitments given the logistical infrastructure it possesses as well as the financial capabilities. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman asserted that the country is committed to allocating $20 billion for this corridor as part of the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII).[4] The move is driven by the growth rate posted by Saudi Arabia at the level of the G20 in 2022. The country also achieved advanced positions in terms of individual productivity rate according to international criteria; and it is the global stabilizer of oil markets. This enhances the country’s standing in the global economic arena. Domestic developments coupled with the shifts in the global arena are prompting European countries to effectively engage in the implementation of the corridor. This is reflected by the EU’s stance, particularly Italy, France and Germany, which all are staunch supporters of the project.

The Parties Involved Adopting an Inclusive Rather Than an Exclusive Approach

This corridor differs from others in its category in that it is founded on the participatory approach (the partnership principle) as opposed to the centralized approach, which is the centrality of a particular nation that typically captures the largest share of interests, benefits and revenues. This is the most outstanding feature of this proposed corridor. It is created in a way that does not only advance the objectives of a particular nation, which aspires to become the hub of this transnational, international network and infrastructure. Instead, it has been planned to forge a true global partnership that maximizes the interests of all parties. It is both the most significant motivation and opportunity.

The aforesaid feature, along with the US support and backing of the project as part of its strategic competition with China, constitute the project’s most salient features, setting it apart from other corridors. At the same time, it forms part of a series of opportunities that incentivize the process of moving ahead with implementing the corridor.

Potential Economic Objectives and Gains

The ambitious project aims to develop infrastructure and logistics connecting East and West in vital fields of high priority on the agenda of contemporary global interests and priorities in a manner commensurate with the growing needs associated with development. This includes conventional, new and renewable energy, technology and digital transformation, digitization, fast data transfer and commodities trading. All this would be done through energy and data transfer cables as well as extending railroad networks to transfer an array of commodities.

After completing the project, spanning thousands of kilometers and connecting Asia to Europe, a host of economic gains will be achieved. These gains will not only encompass the countries located along the corridor’s route, but also the surrounding nations as well as the global economy. This will be clarified in the following points:

Laying the Foundations for a New Phase of Strengthening International Trade Movement

- It is projected that the corridor will help move goods between the ends of the corridor 40% more quickly than is possible at present. India and the Arab Gulf nations have significant trading ties. After China in terms of trade, India is Saudi Arabia’s second-largest trading partner ($53 billion in 2022/2023). India ranks third among the UAE’s trading partners ($85 billion in 2022). Saudi Arabia’s trade with the Eurozone, on the other side of the corridor, reached $70 billion in 2022.[5]

- The establishment of the corridor will lead to creating new trade corridors that are complementary or rival, rather than an alternative, to the traditional routes such as the Suez Canal, through which passes 22% of the world’s container trade. Even the China-sponsored Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) could intersect in one way or another with the new corridor or use the same routes of the proposed IMEC. Compared to the massive role played by marine tanker shipments, which carry around 90% of all global trade,[6] land and rail transport cargoes have a small role. However, the advantage of rail transportation is that it is a rapid means of transportation, which is advantageous to the nature of some shipments and items, such as perishable goods or some raw materials and goods. Furthermore, the new corridor could be used in times of geopolitical crises.

The Growing Share of International Economic Influence of the Parties Involved

The signed memorandum includes important economic and trade heavyweights in the global markets, particularly in the fields of trade, exports and energy, not to mention the contributions to global GDP. The following schedule shows the economic indicators for 2022. We find that the Eurozone economy contributed 12% to global GDP, with commodities and services exports accounting for 25% of global commodities and services. India alone contributed 7.3% to global GDP and a 2.5% share of the world’s total exports, with a major consumer market that is home to 18% of the world’s population.

Saudi Arabia alone contributed 1.3% to global GDP and accounted for 1.4% of the world’s exports, in addition to exporting 14% of the world’s oil. The Middle East and Central Asia, meanwhile, had a 7.6% share of global GDP and 6.7% of the world’s exports, with a huge market encompassing 11% of the world’s populace.[7] This means that trade opportunities among these parties are both promising and could influence the global economy.

Table 1: Global Indicators for 2022 of IMEC Countries

| Country | GDP Share | Exports Share | Population (out of the global populace) |

| Eurozone | 12% | 25% | 4.4% |

| India | 7.3% | 7.3% | 18.3% |

| Saudi Arabia | 1.3% | 1.4% (14% of the world’s oil exports) | .04% |

| Middle East and Central Asia | 7.6% | 6.7% | 10.7% |

Source: IMF.[8]

Maximizing Economic Gains and Opportunities for All Parties

- It is expected that the project would take advantage of the conventional resources (oil and gas) of the Gulf states in general and Saudi Arabia in particular. They will be connected with direct pipelines that meet the needs of neighboring markets in dire need of energy such as India and Europe. This means that conventional energy resources can be exported at a minimum cost and at a maximum profit. This also means ensuring sustainable markets for this commodity as well as enhancing the energy security of these markets through diversifying energy supply options.

- Increasing the interconnection between India’s ports and those of the Gulf states and Europe, thereby increasing trade flows between the two sides. This will facilitate swift transportation from ports to consumer markets via high-speed rail, not to mention the increase in energy exports from the Gulf states to Europe via electricity cables.

- Creating job opportunities and opening new consumer markets, plus the possibility of engaging and benefiting other countries in the region adjacent to the corridor such as Iran and the rest of the Gulf states via ports on the other side of the Arabian Gulf. Egypt could also benefit via the Red Sea ports or the Suez Canal in case the corridor extends to the Red Sea coast.

- Supporting global efforts to shift to renewable and clean energy and taking advantage of the potential and resources of the Gulf states such as solar energy, wind power and hydrogen. This is in addition to attracting foreign investment in these fields and diversifying regional countries’ exports. There will also be support for Europe’s strategic objectives in this regard, particularly after the energy crisis it suffered following the Russia-Ukraine war.

Bolstering the Gulf States’ Standing on the Map of Global Supply Chains

- Strengthening global supply chains and transforming the Gulf, particularly Saudi Arabia, into a vital global transport and logistical hub. This is in order to support the economic diversification plan as part of Vision 2030 and rendering effective the Global Supply Chain Resilience Initiative launched by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in 2022, for which $3 billion from the government budget was allocated.

- Transforming Saudi Arabia into a regional and global hub in the field of digitization and high-speed communications. This will accelerate the Middle East’s shift toward digital transformation.

Mitigating the Impact of Potential International Emergencies on Global Trade

This would happen through contributing to the continued flow of international trade during geopolitical emergencies and crises that the major conventional waterways — on which the world is depending — could face.

Enhancing Cultural Bonds Among the Countries Located Along the Corridor

If completed, the corridor would lead to enhancing cultural bonds among the corridor’s contributing nations in addition to boosting tourism, with an increase in tourism between the ports connecting the corridors and the railroads passing through the major cities and capitals along the economic corridors across the Gulf such as Abu Dhabi and Riyadh. This is in addition to the possibility of connecting to the Arabian Gulf high-speed train project, while reducing the intensity of competition and instead promoting collective advancement.

Implications and Significations of Announcing the Global Corridor

The declaration of the new corridor is expected to have a number of implications for the countries located along its route. Foremost among these implications include the following:

Asserting the Standing of Saudi Arabia and the UAE Regionally and Globally

Saudi Arabia and the UAE’s participation in the proposed corridor, which seems to be of utmost priority for the Biden administration, point to two important issues. The first is the Saudi-Emirati success in emerging as two essential actors in the current regional and global interactions to the point that they cannot be bypassed. This repositioning came in the context of diversifying partnerships rather than alignment or siding with a certain camp over the other. Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states prioritize balanced relations, abandoning alignment with axes and supporting regional security. The second is the shift in the US approach to the Gulf states. The proposed project reveals that the Biden administration has undergone a substantial review and has transformed its strained relations with the Arabian Gulf states. Biden’s remarkable reception of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman during the G20 summit, focusing on Saudi Arabia’s role during the G20 summit and on Saudi Arabia and the UAE in the project are of particular significance with regard to the Biden administration’s desire to integrate Riyadh and Abu Dhabi into one of the world’s US-sponsored economic projects. The US move is indicative of the two regional powers’ economic significance and geopolitical clout, which would help assert Washington’s standing on the international arena. This in turn could help restore the lost trust, bringing relations back to their effective, strategic nature. [9]

The Desire to Further Stabilize the Middle East

The region’s countries, particularly the Gulf states, pay special attention to the economic aspects. There is a desire to move to the post-oil era, diversify economic sources, rely on clean energy and achieve technological quantum leaps in light of global artificial intelligence advances. The IMEC will help increase mutual reliance among these countries, boost opportunities, curb the state of negative competition and dispute and achieve economic cooperation between the countries of the region through which it passes. It is expected that the corridor will contribute to the upgrade of infrastructure and the revival of transportation companies and that cooperation will include connecting ports, enhancing trade movement and transferring technological expertise and energy surpluses from the region’s countries, given the influential international participation.

In addition to international measures, attempts are being made to achieve regional stability among the region’s countries. This is supported by the fact that the region’s governments are opting for truce and conflict resolution, and that the economic factors, in light of the regional and international challenges, are pushing in this direction. By virtue of this corridor, the Gulf states could become a point of connection between Europe and Asia and an economic hub influencing global trade, which enhances Asia’s standing, thus making it the center of power in the future.[10]

Supporting and Increasing India’s Presence on the Global Stage

The environment and timing of announcing the corridor indicates that the project is inextricably linked to the mounting cutthroat geopolitical competition between the United States and China over the leadership of the global order. This competition has recently been manifested in two courses: the first is expanding alliances and blocs. The second is the competition over international interconnection corridors.

With regard to the course of building and expanding alliances and blocs, the IMEC is enhancing the alliance with the United States in the Old-World continents and contributes to its policy aimed at encircling China, whether in its geographical neighborhood or at the international level. Perhaps the United States has succeeded, through this project, to send a message that the Chinese attempts to build blocs hostile to it and expand other groupings do not pose a major challenge to Washington’s standing. The corridor, the welcoming by the countries that are expected to join it, some of whom are invited to join BRICS, reveals Washington’s ability to exert influence and affirms that the United States holds most of the levers enabling it to control the global order despite the Chinese attempts to downplay the corridor and the impact it could have.[11]

In addition, the corridor — if successfully implemented —will help qualify India to become an economic counterweight to China in its geographical sphere and Lebensraum. The project will position India as a legitimate alternative to China in international trade, as well as an alternative to China in the Middle East and Europe. This step will undoubtedly assist India in settling on a position regarding US-Chinese competition, which comes in light of New Delhi’s aspiration for a larger global role and attempts to take advantage of ongoing international realities to shift Western investments to its territory rather than China, allowing the West to rely on it as an international trading partner rather than China.

With regard to competition for international interconnection corridors, the proposed corridor could be considered as an initiative rivaling the China-sponsored BRI, thus becoming an alternative consistent with the US desire. Through the BRI, China seeks to enhance its international standing; and the United States, meanwhile, through its partnerships spanning the three continents, in addition to the capabilities of its partners, is forging an economic partnership of a strategic nature that could negatively impact China’s progress on its megaproject.

Building on the foregoing, the corridor could impact China’s regional and international clout, including its clout in the Middle East, which is under close scrutiny from the Biden administration. The latter has reiterated that it will not allow Russia and China to fill the vacuum in the region. Of course, China will not stand idly by in the face of such a project that takes aim at its global aspirations. It could add more weight to its project and increase the financing which could water down the impact of the proposed corridor and maybe thwart it. Yet China will continue its efforts to enhance the alliances and blocs it leads such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS. Additionally, China could view this project as a source of threat to its ambitions and economic standing. Accordingly, it could lead to spoiling its relations with some of the region’s countries and impact its growing partnerships with these nations.[12]

Thus, it could be said that the project will heat up geopolitical competition between China and the United States in the East Asia region, extending westwards. This comes in light of the intersection of international interconnection corridors and the conflicting interests between the countries through which these megaprojects pass.

The Possibility of Easing the European Dilemma

The Russia-Ukraine war as well as the preceding Covid-19 pandemic have created enormous challenges for the European continent. The continent is living through a dilemma not seen since the beginning of the 21st century, with Russia suspending gas exports to Europe, a lever deployed against European decision-makers for their military support for Ukraine against Russia. Europe fears the potential consequences of a Russian victory over Ukraine in the war for European security and stability, not to mention the continent’s need for energy and trade. International reports have revealed that the EU is facing a natural gas shortage estimated at billions of cubic meters through 2023.

If completed, the corridor is expected to ease the European crisis resulting from the Russia-Ukraine war. The European Commission has described the corridor as a massive strategic project that connects the region with the Indian and Pacific oceans and the Mediterranean. The project is also in harmony with European objectives in terms of creating global trade alternatives. The EU previously allocated €300 billion for infrastructure projects overseas during the period from 2021 to 2027.[13] The continent is racing to remove the economic levers from Russia’s hands. After withdrawing the energy — oil and gas — levers, there remain some challenges, attention has turned to trade, out of a European desire to increase Russia’s isolation. The corridor also enhances connections with Arab, Gulf and Asian actors who have become effective and influential on the map of international political and economic interactions, which explains Europe’s staunch support for the project.

Europe could also benefit from the position of the parties involved in the corridor who have close ties with the Russians in order to influence the Russian position on the Russia-Ukraine war. This is in addition to providing a trading alternative by increasing trade with India, Saudi Arabia and the UAE — without the need to engage in trade with Moscow — especially given the current strengthened Europe-Gulf relationship and the possibility of Europe making trade and economic gains that end its crises. The corridor will allow the continent to optimize its exports while also allowing supply chains to move more quickly and via shorter routes across the Middle East and Asia. The corridor, on the other hand, will allow Europe to import crucial supplies at a faster rate.

Global Positions and Reactions

International reactions have varied, with countries welcoming the corridor (the direct stakeholders with interests in establishing the corridor, and indirect but supportive parties such as the United States and the EU). However, there are countries that question the possibility of carrying out the project, its benefits or its implications for the future of their corridors. This includes the countries that fear their interests and place on the map of global corridors may be undermined such as China, Iran, Turkey, Pakistan and Egypt. The following indicates the most salient positions of these countries toward the project:

China

China has considered the proposed economic corridor a welcome initiative.[14] Beijing previously welcomed all similar regional and international initiatives which help developing countries enhance and bolster their infrastructure and connect them to international corridors — as long as they are not weaponized or used as a tool to strengthen the geopolitics of certain nations at the expense of others outside the corridor’s scope. However, despite China officially welcoming the corridor, the Chinese geopolitical concern appears evident, according to what was reported by the Chinese media and political circles.

The Chinese concern could be construed in the context of the cutthroat international geopolitical competition with the United States, the world’s most powerful state which is seeking to encircle China globally and hold on to the monopolar global order versus the multipolar world order sought by China. It is also construed in the context of Beijing’s establishment of a similar international transboundary trade corridor (the BRI) launched by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013. The corridor has been a geopolitical step from which China has taken advantage of its direct and indirect neighbors in the Middle East, Africa and Central Asia through rallying support from several emerging markets referred to as the Global South. This has led to enhancing relations with the countries located within the BRI’s scope, particularly economic relations.

Some Chinese voices believe that the proposed Indian corridor could restart the discussion about assistance in the field of development and infrastructure globally, thereby undermining China’s advantage and leading to its emergence as a global rival. This would happen through finding options that could be alternatives to the Chinese project. Opinions have differed on this point; some hold the view that the new corridor will surely bring about some competition and will have some impact on the BRI but could also supplement the Chinese project in light of the attempts by all stakeholders to revitalize the global economy through facilitating the transfer of commodities, technology, raw materials and industries. There perhaps could be a door open for Chinese firms to invest and sign agreements to carry out sub-projects by offering primary products and complementary services for future projects.

Iran

Iran has considered the proposed corridor as one of the several global corridors surrounding its geographically. However, the corridor passing through neighboring countries excluding Iran is viewed by the latter as an exclusion from the corridor’s routes.[15] And this reflects a negative international outlook for Iran, its credentials and infrastructure required for acceding to international corridors. This comes despite the fact that Iran possesses an important geopolitical position and resources similar to that of Saudi Arabia. But the difference (between the two nations) lies in their ability to create competitive advantages out of their geopolitical locations by connecting with the world and creating an influential role regionally and globally.

Iran views with suspicion the advance of its rivals in the region toward enhancing their positions and securing their integration into the global economy and the trajectories of development at a faster rate. Conversely, Iran has lost the ability to take advantage of its geographical location in securing economic and trade gains through participating in corridor projects and international economic development. This presents Iran with an additional challenge, coupled with the exacerbating internal and external crises in Iran.

Excluding Iran from the proposed corridor reveals that the Iranian model of governance has created a state unqualified for international development participation. This is due to the fact that Iran has become a crisis-ridden nation at home and is bearing the brunt of the economic siege externally. The security apparatuses are controlling the decision-making processes. Therefore, Iran’s standing has declined in terms of participation in global corridors, since its priorities include the pursuance of nuclear and expansionist policies rather than focusing on development and civilizational policies which aim to build both the state and citizens. Thus, Iran has lost the qualifications for the role required to be part of the world’s global corridors, thereby losing the support of the actors holding the biggest sway in establishing these corridors. Iran’s status as a priority for several projects on international corridors such as the International North-South Transport Corridor, the BRI and the Zangezur corridor, despite its geopolitical position, promising resources and economic, trade and investment opportunities.[16]

Perhaps the proposed corridor, as well as the other corridors, will encourage Iran to turn inwards, rebuild a suitable infrastructure and develop the economy rather than support expansionist projects, which may be one of the reasons why its significance on the map of global logistical projects has declined.

Turkey

Turkey has expressed its stance on the proposed corridors through official remarks by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The Turkish president has revealed his opposition to the corridor since its current structure bypasses Turkey.[17] He considers his country to be the most suitable for the passage of trade between East and West, “There will be no corridor without Turkey. And the most suitable route for the passage of trade from East to West is the route passing through Turkey.”[18] He reiterated a previous proposal to establish an alternative corridor connecting the Gulf states to Europe via Iraq and Turkey, called the Development Road. This is what Erdogan attempted to promote during his recent trip to the Gulf states, which included Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, Oman and Iran.

The Development Road faces multiple challenges, foremost of which are those facing the country that has proposed the project, Iraq. This is in comparison to the IMEC in terms of the powerful nations involved, the level of stability, financing and advanced infrastructure. Baghdad is suffering from political, economic and security crises. This is added to the passage of the project in the regions disputed between the government of Baghdad and the Kurdistan Regional Government, the security challenges posed by the proliferation of arms outside state control and the refusal of the armed militias to hand over weapons to the state, all will cause the rest of the countries located within the project’s scope to question the possibility of the project’s success. There are also challenges related to the sources of financing of the project and the divergent positions of the states located within its scope. Every single state will have its own position on the project, a position associated chiefly with their calculus of the level of profits and losses from the project. Additionally, there are complicated disputes and crises between many of the countries that are proposed to partake in the project. The infrastructure in some of these countries is dilapidated due to the prevailing political and sectarian disputes which have been raging for years.

Map 2: The Proposed Development Road

Source: https://cutt.us/Bg8T3

Pakistan

Pakistan[19] views the issue of its exclusion from the proposed corridor with doubt and suspicion due to considerations related to the efforts of the Pakistani government to open the border and trade with India. The aim is to make Islamabad a hub for logistical and trade transport at the heart of the multiple global logistical and trade projects. Yet Pakistan fears being impacted due to the potential implications for the transnational Chinese project (BRI). Pakistan is part of the Chinese project. In the context of growing Gulf-India relations, enhanced by ambitious economic interconnection projects, it is a relationship that Pakistan does not favor or prefer, for fear of impacting its bilateral relations with the major Gulf states. This comes especially in light of the historical competition between Islamabad and New Delhi in attracting the Gulf states to side with one party over the other.

Egypt

The proposed corridor has stirred up controversy as to whether it will impact the future of Egypt’s Suez Canal, the linkage between the East and Europe. About 13% of international trade passes through the Suez Canal, a considerable level compared to other international corridors. In addition, 22% of the world’s container trade passes through the canal.

Due to the difference in the nature and cost of transport between the two corridors, and also because of the large number of containers transported by huge tankers at a significantly low cost, several discussions have circulated in the Egyptian media that the proposed corridor cannot be considered a strong rival to the Suez Canal. Still, it could reduce the transport movement through the canal to an extent. They do not view the corridor as an alternative to it or something that will significantly impact it.

Potential Challenges to the Implementation of the Corridor

Despitethe opportunities available for moving ahead with the proposed project, it is likely that the IMEC will face challenges of various dimensions: political, economic and security. These can be summed up in the following points:

Political Challenges

The IMEC stands out as a rival to China’s BRI, which enables some parties such as Saudi Arabia to diversify its options and benefit from both projects in a way that serves its economic interests, whether producers, consumers or for transit purposes.[20] However, there will be wrangling among the competing actors. It is likely that the coming years will see the establishment of new alliances and organizations against the backdrop of the development of the global map of corridors. This will lead to a competition that sees each alliance attempting to weaken its rivals’ projects using various tools and methods, which will prevent the realization of the project’s objectives.

There are several parties such as China, Iran, Turkey and others that are wary of the impact of the proposed corridor. These countries, individually or collectively, have the ability to create alternative frameworks for cooperation. The project will impact existing political alliances, pushing those impacted to search for their interests with other powers. In light of the Chinese corridor, Beijing could make concessions to the other countries involved (offer advantages) to render the IMEC a failure.

Notwithstanding the attempts by the parties involved to confine the project to the economic sphere, separating it from politics will be highly difficult. The Russian and Chinese presidents missing the G20 summit is one of the indications of the influence of geopolitical contexts. In one of its dimensions, the project is considered an indirect threat to China and Russia’s interests as it opens up new corridors that undermine the Chinese route. It will also provide Europe with energy, thereby amplifying its geopolitical significance compared to Russia and its ability to employ the geo-economic dimension in its competition with Europe, as was the case at the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine war. From this perspective, it is not unlikely that Russia could take advantage of the resentment of the parties impacted, forging alliances with them with the aim of undermining the opportunities for the success of the corridor.

Economic Challenges

The high financial cost of such corridors poses an important challenge to their progress, especially in times of economic depression or decline in global oil prices. We speak here about hundreds of billions of dollars that should be allocated to purchase a large number of new trains, extending railroads, installing electricity cables, energy pipelines and digital fiber cables extending thousands of kilometers, not to mention developing the maritime and overland infrastructure along the corridor’s route. This requires drawing up clear financial plans and timeframes to ensure compliance with the implementation of this vital project.

In addition, transporting commodities via trains, though speedier, is not necessarily lower in cost compared to maritime transportation via containers which account for 90% of global trade. This is because the maritime means of transport carry massive amounts of containers on every tanker, which reduces the cost of transporting a single container compared to rail transportation. This is compounded by the need to load and unload cargo on two additional occasions if the proposed corridor is completed. The first occasion will be at the Arabian Gulf ports after arriving from India while the second will be from the Israeli port, before heading to the European continent, and vice versa.

However, carrying commodities by rail has the advantage of providing quick transit for perishable products as well as those that are light and expensive. The Gulf states will benefit more from it in terms of ensuring food security and lowering the cost of food imports from India through the faster transport of its imports from India to the eastern ports where delivery takes place on the Arabian Gulf, as well as the major consumer markets in Riyadh, Abu Dhabi and Dubai. This is because there will be no need for loading and unloading, as well as the previously noted benefits of the corridor.

Security Challenges

The corridor’s length could face some security challenges. The corridor’s heart is the crisis-stricken Middle East with some of the participating countries involved in the ongoing conflicts as well as regional and international parties such as the dispute between Israel and Iran and between Israel and Iran’s proxies. Therefore, parts of the corridor could fall within the range of Iran’s fire in case of any potential confrontations. The corridor will pass through areas where the interests of several regional and international actors intersect; there could be escalation at any time to protect these interests.

Among the challenges is the fact that the confrontation and competition between the backers of competing corridors is not confined to these countries directly. New fronts could be inflamed in various parts of the world with the underlying aim of one corridor dealing a blow to the other. This is highly plausible given that India and China overlap in some spheres of influence in Asia. For example, if Iran finds itself excluded from these economic projects and suffers exacerbating political and social crises, it could go back to square one, spoiling its relations with Saudi Arabia in order to sabotage these projects. In this context, it is worth noting that technological advancements reduce the importance of the geographical dimension in terms of influencing the corridor. It is not unlikely that proxy actors affiliated with Iran or other parties would carry out strikes against the corridor using missiles or drones, which have been commonly used in wars in recent years.

Conclusion and Findings

The significance of the criteria related to a country’s geopolitical location on the map of global trade and logistical corridors is increasing, given that these criteria have emerged as important indicators for measuring state strength and the effectiveness of different models of governance and administration. In addition, geopolitical factors can be used as tools for exerting influence regionally and internationally and increasing a country’s weight in the strategies of major international actors — as they thus become actors that cannot be bypassed when outlining the future of the region and the world. The following are the most prominent results of the study:

The Expansion of Saudi Arabia’s Influential Role, Transcending From Regional to Global

The study’s premises highlighted international actors’ awareness of the importance of including qualified and stable Arab and Gulf actors into their global corridors for the latter’s effectiveness to be ensured. The study also revealed that Saudi Arabia is among the stable countries eligible for linkage with the global corridors, given the country’s unique competitive advantages. The Saudi leadership has sought to enhance and increase the impact of these advantages on the global map through a policy of good governance at home that has fostered security and stability and a balanced foreign policy overseas that has enhanced the confidence of major international partners. Therefore, the competitive advantages possessed by the country are recognized by global actors. This gives Riyadh a central position not only for defining the future of the Middle East but also for maximizing its influential presence on the intentional political and economic arena. This is because of its ambitious vision and the realization of its leadership to transform these competitive advantages into sources of exerting influence overseas that maximize the country’s standing and role in regional and international affairs. The proposed corridor has drawn attention to the repositioning of the Saudi geopolitical location in international trade corridors.

Arab Actors Shifting From Merely Adapting to Policies to Formulating Policies

The study has also revealed an important step down the road of dispensing with the traditional rules represented in the Arab nations adapting to international policies — of a unilateral Western character. Though preliminary, this shift signals hope for Arab countries that they will transition from a world shaped by others to the stage of engaging and even initially taking steps in creating a world that other actors cannot shape alone, but rather with the participation of Arab and Gulf actors. Saudi Arabia, the only Arab member of the G20, has won the right to play a part in shaping the region and the world’s future according to its vision for building strategic partnerships with major international actors exerting huge influence over international affairs such as the United States, China, India and the EU. At the G20 summit, the Saudi role shifted from mere participation to the actual development of initiatives. The centrality of the decision-making pertaining to the world’s future, is, by extension, no longer outlined in the corridors of the UN and its agencies, led by the United States, foremost of which is the Security Council. Rather, this process of decision-making has moved to other international organizations and entities such as the G20, BRICS and the Group of Seven.

Foreign Policy Models and Roles a Criterion for State Strength

Among the study’s prominent results, in addition to the transformations in the standards used to gauge state strength in light of the major global shifts, is that the world’s future cannot be shaped only through military force available to certain countries although it remains an important indicator during wars. Rather, the world’s future could be shaped through the ability to create roles and develop frameworks, not through policies that could destroy capabilities of countries and weaken them as a means for the rise of this state. Rather, this would happen through an ambitious civilizational and developmental strategy that focuses on transforming a state’s capabilities to tools of exerting outside influence. This begins essentially with focusing on building individual character, technological progress, innovation, combating unemployment, poverty and corruption, making commodities available, conducting foreign trade and respecting countries’ sovereignty and territorial integrity. Thus, Saudi Arabia has presented a different model, setting a unique example for regional and international actors to follow in terms of how to create a role and model through the available national capabilities and resources rather than destroying the potential and resources of countries and peoples.

The Opportunities for Establishing the Corridor Outweigh the Challenges Facing It

The study’s premises indicate that the advantages of the project outnumber the obstacles facing it, given the weight of the countries involved in this massive corridor on the global political and economic maps. This is in addition to the relative harmony among the countries involved, and their strategic need for completing the corridor, given its important global geopolitical implications and gains, which could lead to strengthening these countries’ standing on the global stage. For example, all parties agreed before leaving India to arrive at a swift action plan for the project while taking into account the possibility of seeing surprising new shifts on the global stage which could impact the countries’ decisions in relation to its implementation and the fulfillment of their pledges in this regard.

The Possibility of Stepping Up Global Geopolitical Competition

Perhaps China missing the G20 summit meeting, according to the study’s premises, is related to Beijing’s belief that the West — Europe and the United States — is working to move the international geopolitical competition to the Asian arena — thereby pitting India against China. The West, according to the Chinese belief, enhances India’s strength and role in Asia and globally, with the Indian Dream intended to turn into the most powerful rival to the Chinese Dream, given New Delhi’s numerical population superiority and technological edge. This point in particular is a good maneuver by the United States, revealing that it still retains levers of power. China also views the US move as part of its policy to reach agreements with allied Asian powers in order to deprive Beijing of its “factory of the world” status by betting on increasing the strength of India and other allies against Beijing. It is no accident that Vietnam was the second stop on Biden’s tour after New Delhi, thus sharpening competition over the global economy that involves global logistical and economic corridors and axes.

Another Challenge Added to the Host of Challenges Facing Iran

The study has also revealed another external challenge facing Iran: it lacks the required qualifications for joining global trade and logistical axes despite its geopolitical location and massive resources. This could be attributed to the priorities of the Iranian model of governance and administration. This model has resulted in a state reeling from economic, social and security issues, with the ruling establishment prioritizing regime survival over citizens’ wellbeing, which is a top priority in the Saudi worldview. This is also evident in the effects of the siege on the Iranian economy. As a result, Iran’s competitiveness in joining global economic and logistical corridors such as the International North-South Transport Corridor has diminished. Moreover, Iran’s opportunities within the BRI have been limited, in addition to its exclusion from the IMEC. This is simply because it has not been qualified in terms of infrastructure, financial capacity, or ability to capitalize on investment opportunities.

To conclude, preparing models for globally influential external decision-making needs a leadership that is well aware of the state’s relative capabilities and competitive edges. Moreover, the leadership should know how to transform these capabilities from a state of latency to potency on the condition that they should maximize the state’s standing and weight in the regional and global sphere, with the outside world sensing this role in the region and globally — as is the case with Saudi Arabia, which is a rising and influential power due to its maximization of regional and global tools of influence and levers. This is happening through an ambitious national vision that relies on a dynamic and stable economy as well as a wise and well-considered policy that takes into account the country’s domestic interests in the first place while at the same time strengthening relations with the outside world. In doing so, the country adopts principles such as good neighborliness, noninterference and seeking to achieve grand ambitions for the sake of this global model.

[1] “Memorandum of Understanding on the Principles of an India–Middle East– Europe Economic Corridor,” The White House, September 9, 2023, accessed September 18, 2023, https://cutt.us/TCfhb

[2] “At G20, US, India, Saudi, EU unveil alternative to Belt-and-Road,” Euractiv, September 10, 2023, accessed September 18, 2023, https://bit.ly/4009fUo.

[3] “First Industrial License in Oxagon for NEOM Green Hydrogen Company Issued,” Al Arabiya, February 1, 2023, accessed September 18, 2023, https://cutt.us/XRCjM. [Arabic].

[4] “G20 Summit: ‘Economic Corridor’ in Parallel With the ‘Belt and Road!’” Sky News, September 11, 2023, accessed September 18, 2023 . [Arabic].

[5]“The Direction of Trade Statistics, Exports and Imports by Areas and Countries,” IMF, September 15, 2023, accessed September 18, 2023, https://cutt.us/cBh2c.

[6] “Shipping and World Trade: World Seaborne Trade,” International Chamber of Shipping, September 16, 2023, accessed September 18, 2023, https://cutt.us/CidJk.

[7] “World Economic Outlook: A Rocky Recovery,” IMF, April 2023, 120, accessed September 18, 2023, https://bit.ly/3FnKMyX.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Abdel Aziz Aluwaisheg, “The Far-reaching Implications of the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor,” Reuters, September 12, 2023, accessed September 19, 2023, https://arab.news/v3dz5.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ahmed Aboudouh, “An India–Middle East–Europe Corridor Is Unlikely to Boost Saudi–Israel Normalization,” The Guardian, September 15, 2023, accessed September 19, 2023, https://bit.ly/404lvDF.

[12] Mihir Sharma, “This Silk Road May Actually Lead Somewhere,” Bloomberg September 14, 2023, accessed September 19, 2023, https://bloom.bg/48X3CKS.

[13] “US-European Support for a Corridor Linking India to the Middle East,” Independent Arabic, September 9, 2023, accessed September 17, 2023, https://cutt.us/e2fJj.

[14] “China Says It Welcomes India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor So Long It Doesn’t Become a Geopolitical Tool,” The Economic Times, September 12, 2023, accessed September 13, 2023, https://bit.ly/3raIXCb.

[15] “Iran’s Exclusion From the Silk Road and the Officials Deceived by the Temporary Agreements/ Iran’s Exclusion From the Three Corridors North, West and South,” Economy 24, accessed September 13, 2023, https://bit.ly/3rl4gkr. [Persian].

[16] Mohammed Alsulami, “Why Iran Is Ignored When Nations Plan Transboundary Trade Routes,” Arab News, September 19, 2023, accessed September 20, 2023, https://www.arabnews.com/node/2375786.

[17] “Erdogan Says No India-Mideast-EU Economic Corridor Without Turkey,” Middle East Monitor, September 12, 2023, accessed September 12, 2023, https://bit.ly/3rmJCAg.

[18] “Erdogan: Turkey Is Most Suitable for the Economic Corridor Between India and Europe,” Anadolu News Agency, September 11, 2023, accessed September 16, 2023, https://cutt.us/BAA07.

[19] “Why Did Pakistan Get Upset Due to India’s Proximity to Saudi Arabia?” India Posts English, September 12, 2023, accessed September 13, 2023, https://bit.ly/3LtoCPn.

[20] According to columnist Abdul Rahman al-Rashed, Saudi Arabia sells 2 million barrels of oil to China and roughly 1 million barrels to India. The two countries are Riyadh’s two main markets today and in the coming years. In 2030, India’s oil imports will rise from 5 million to 7 million barrels per day, contrary to Prime Minister Modi’s vow to cut imports in half. According to estimates, its imports will more than double. Rising nations will intensify rivalry over geographical oil resources, particularly in the Gulf. It was a critical pillar in major countries’ high-level policy plans till the middle of the 20th century. See: Abdul Rahman al-Rashed, “Our Region Between the China Belt and the Indian Corridor,” Asharq Al-Awsat, September 11, 2023, accessed September 18, 2023, https://2u.pw/XyGsUkl. [Arabic].