Contrary to the expectations of Iranian observers, Iran has resumed uranium enrichment up to 20 percent after duly notifying the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The new nuclear law passed by Iran’s Parliament is intended to ratchet up the country’s nuclear activities. According to the law, Iran will enrich uranium up to 20 percent, install 1,000 advanced centrifuges and produce at least 120 kilograms of highly enriched uranium.

Ali Akbar Salehi, the head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI), told a Persian-language news site, “Based on the latest news I have, they are producing 20 grams (of 20 percent enriched uranium) every hour, meaning that we are practically producing half a kilo every day.”

Kazem Gharibabadi, Iran’s Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the UN in Vienna, added more clarity by tweeting, “The IAEA DG reported today that upon provision of an updated DIQ for Fordow, the Agency carried out a DIV at the Site and confirmed that a cylinder containing 137.2 kg of uranium [enriched] up to 4.1 percent has been connected to the feeding line and production of UF6 enriched up to 20 percent started.”

When the Iranian Parliament passed the nuclear law, which was eventually approved by President Hassan Rouhani, it was viewed as an Iranian attempt to exert further pressure on the new incoming US administration rather than Tehran proceeding with another consequential violation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Amongst the JCPOA signatories, only Russia backed Iran’s move to increase its enrichment levels while blaming US policy towards Iran. Tehran mentioned that its move is in line with its correspondence with the IAEA in 2018, when the United States withdrew from the JCPOA. It informed the nuclear watchdog about its plans to produce silicide advanced fuel. Its argument, prime facie, remains that the use of uranium metal as an intermediate product to produce uranium silicide fuel is safer and better than the currently-used uranium oxide-based fuel. As per the JCPOA, Tehran cannot enrich uranium beyond 3.67 percent, however in order to pursue its nuclear deterrence program, it must possess the strategic metal with 90 percent enrichment levels.

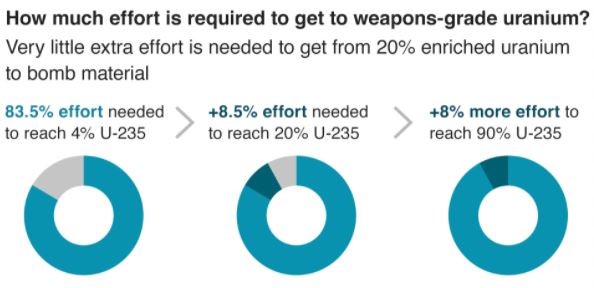

Prior to the JCPOA, Iran was enriching uranium at 20 percent, thus, its resumption will not be a technological feat. Though Tehran has not removed IAEA monitoring equipment or its inspectors, there is still a red flag. Iran enriching uranium up to 20 percent will drastically reduce the effort needed to get to 90 percent enrichment levels that are necessary to make a bomb. The effort required to reach the different enrichment levels is illustrated in the diagram below (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Effort Required Reaching Weapon Grade Uranium

It begs the question: why worry if Iran is keeping the IAEA in the loop while complying with IAEA inspections and verifying its commitments? Critics see it as an anticipatory Iranian move to go nuclear. Here is how: if the prospective talks with the Biden administration fail to yield Iran’s desired outcomes, it can notify the UN about quitting the NPT with a three-month notice period – in line with its oft-repeated threat and following in the footsteps of North Korea – and conveniently “dashing” to the nuclear bomb.

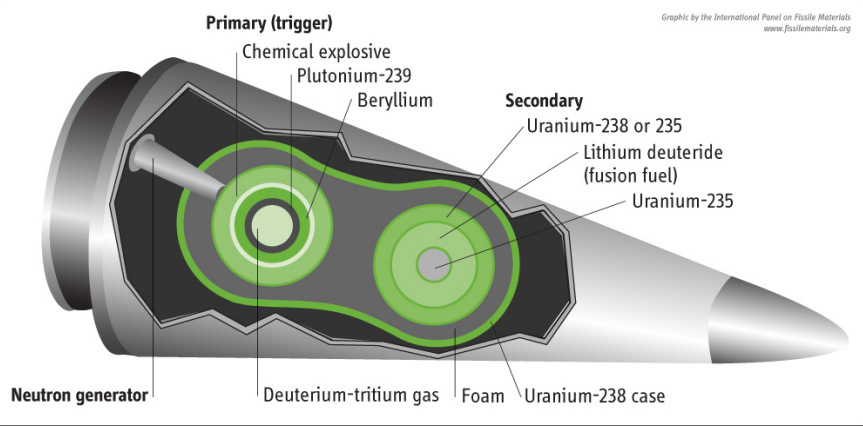

Khamenei’s decision to “break-out” and build one or more nuclear payloads will only be hindered by complications in fabricating (i.e. building) the bomb itself, which can also further depend on whether Iran chooses the gun-type or implosion-type bomb. The following graphic (Figure 2) illustrates the fabrication of a nuclear bomb.

Figure 2: The Fabrication of Nuclear Bomb

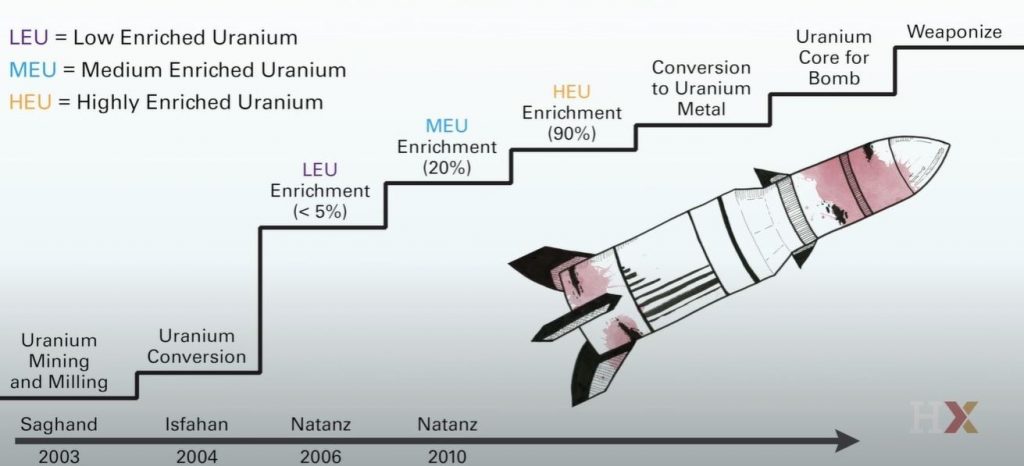

Yet some have argued that Iran had been enriching uranium at 20 percent prior to signing the JCPOA while it could have enriched at much higher levels. They contend that Iran was only raising the stakes prior to the nuclear negotiations and did not intend to produce a nuclear bomb. The following diagram (Figure 3) prepared by the Belfer Center, Harvard University, highlights the mining, conversion, and enrichment of uranium from 2003 to 2010. The Natanz nuclear plant reached 20 percent enrichment levels in 2010 only five years prior to the JCPOA.

Figure 3: Uranium Enrichment (2003-2010)

Iran’s fresh move has heightened concerns in relation to the country’s unknown nuclear enrichment and fabrication facilities which are undisclosed to the IAEA or other countries. Donald Rumsfeld, the former US Secretary of Defense, once famously mentioned in a new briefing about Iraq’s alleged weapons of mass destruction that there were nuclear facilities that were known, known-unknown (that are known to one or more global powers) and unknown-unknowns. In the context of Iran, it is the latter, the unknown-unknowns that will raise the alarm bell if Iran was to exit the JCPOA as well as the NPT. Hence, global pressure and diplomatic engagement can be simultaneously instrumental in reversing Iran’s enrichment-related ambitions and lead to a new broad-based agreement. By ratcheting up its uranium enrichment levels, Tehran is trying to impose more pressure on the Biden administration to rejoin the JCPOA or face the worst-case scenario.