Introduction

Public participation in Iran’s presidential election, held on June 18, 2021, dominated the political scene in Iran, as it was the most significant election ever held in the history of the Iranian republic. The Iranian political system, including all its branches and leaders, emphasized the significance of this election, intensifying their efforts to mobilize voters. On the other side, the opposition groups and individual activists, at home and abroad, called for boycotting the election. The turnout was 48.8 percent; the lowest ever in Iranian presidential elections since 1980 and with approximately 4 million votes cast as blank or void (around 12.9 of the total votes). It was the largest protest vote in Iran’s history. The election outcome exposed important changes in the policy of the electorate, reflecting the more significant changes politically, economically, socially, and demographically.

These changes trigger many questions, most prominently, about the motives behind the government’s keenness on ensuring a high turnout in the 2021 presidential elections; the political, social and geographical aspects of voter turnout; and the ramifications of the election on Iran’s political system amid the current conditions the country is facing. The study aims to answer these questions through discussing four main topics: first, voter turnout amid calls for mobilization and boycott, second, the nature of voter turnout in Iran’s 2021 election, third, the factors accounting for low turnout, fourth, the ramifications of the low turnout.

- Internal Conflicts Between Mobilization and Boycott

Two groups competed in the 2021 presidential elections: one group called for intensifying participation while the other called for boycott. Their positions and motives are explained as follows:

1.1. The Significance of Voter Turnout for the Iranian Political System

It was quite vital for the Iranian political system to make people participate in the election because it has adopted the republican system with periodic elections to transfer power between government institutions and for significant government posts such as the president of the republic, the Assembly of Experts, the Majles (the Parliament) and local councils. It was also highly significant to legitimize the various power structures in the country and the whole Iranian political system. This is in addition to emphasizing the popular support for the principles and continuity of the 1979 revolution, and popularizing the political system’s decisions and policies whether inside or outside the country, ensuring the political and economic interests of the ruling elites, and countering external foes.[1]

Over the course of history, Iran’s political system has prioritized voter turnout, taking pride in intensified public participation in Iran over the last 40 years as it reflects the legitimacy of the system. The voter turnout rates recorded interesting numbers; the lowest turnout reached approximately 50 percent, a good rate in comparison to elections held across the world.

The 2021 voter turnout was ultimately significant for the Iranian political system due to the decline in legitimacy indicators at home, facing unprecedented external pressure, and moving to a critical transfer of power. The election coincided with a series of measures taken by the supreme leader to rearrange the political scene in the country. Among these measures was election engineering, which was undertaken to pave the way for a specific candidate to win the election, namely Ebrahim Raisi. These arrangements aimed mainly to unify the orientations of the ruling institutions as the country is facing the most critical juncture in its history. These measures were also implemented to ensure the continuity of the Velayat-e Faqih ruling system by paving the way for Raisi to be the next supreme leader after Khamenei’s death. Raisi is a strong believer in the revolutionary principles and the perspective of Khamenei and Khomeini. He is, according to the political system, the safeguard of the future of the Iranian Islamic Republic.[2] According to the supreme leader’s representative in the Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) Abdullah Haji Sadeghi, the Iranian political system is in need of “a revolutionary, religious, young, and Velayat-e Faqih government […] a government which obeys the supreme leader and believes that the fundamental system for society relies on the supreme leader. [It is] in need of a president for the republic who is like Qassem Soleimani; a soldier loyal to the Velayat-e Faqih, and whose soul at the same time, is against arrogance and fights the enemies of the revolution.”[3] To legitimize their insistence on election participation, the supreme leader argued that voter turnout is a religious duty and boycotting it is religiously illegitimate. “Based on this fact, if we want to reduce and eliminate the economic pressures of the enemies, i.e. sanctions and other pressures, we must increase the turnout in the elections and show the public support of the regime to the enemies,” Khamenei said in a televised speech.[4] “Those who have influence should call on people to participate in elections as it is a religious duty,” he added.[5] A semi-organized campaign was launched in which all institutions, figures, and parties affiliated with the political system emphasized that voter turnout is a form of defending the republic and countering a foreign conspiracy targeting Iran. The mobilization made the presidential election look like a referendum on the political system itself. Ahmed Khatami, interim Friday prayer leader, deemed voter turnout as voting “yes” for the system of the Iranian Islamic Republic and

“renewing of bay’a (a pledge of allegiance) to the Islamic system.”[6] Sunni clerics joined the campaign, urging people to participate in the election.[7] The general staff of the armed forces also issued a statement calling on people to participate in the presidential election.[8]

To secure large-scale voter turnout, all political parties in the country, including the “reformists” — despite their criticism of the election’s lack of transparency — supported the campaign. Though the Guardian Council excluded and relegated many candidates such as former Parliament Speaker Ali Larijani and former Vice President Eshaq Jahangiri, neither Larijani nor Jahangiri boycotted the election, instead they called on people to participate. Even former President Hassan Rouhani and his Foreign Minister Javad Zarif were called to participate in the election though they had faced wide-ranging criticism during their tenure. Zarif received a political death blow when audio recordings were leaked in which he complained about IRGC interference in foreign policy. The tapes were released to affect his political future.

- The Weapon of Boycott by the Opposition

Boycotting the election for the opposition abroad and many Iranians at home was as important as voter turnout for the Iranian government. The boycott delegitimizes the political system, causing it embarrassment at home and abroad as it does not enjoy popular support.

In a meeting with former Iranian President Mohammed Khatami, the Combatant Clergy Association criticized the rejection of the Guardian Council’s large-scale disqualification of many candidates running for the election, deeming it as “unprecedented negligence” of the people. The council warned that this step would reduce voter turnout. Mahdi Karoubi and opposition candidates in the 2009 election criticized “the illegal interference” in the 2021 election.[9] “I will stand with those who are fed up with humiliating and organized elections and who will not give in to decisions made behind the scenes in secret,” Mir-Hossein Mousavi said in the statement.[10] Moreover, former Iranian President Ahmadinejad announced that he will not participate in the election, calling on the public to cast a blank vote.

At home, some political currents and blocs as well as political figures and activists from religious and “reformist” currents announced they would boycott the election. The families of the victims of the 2009 protests, the Ukraine plane crash, and executed politicians boycotted the election.

Political activists launched social media campaigns to boycott the election months before its due date using hashtags such as “I will not vote,” “blank vote,” “no to the Islamic Republic.” Thirty-two political groups affiliated to three political organizations (Congress of Nationalities for a Federal Iran, the Council for a Democratic Iran, Solidarity for Freedom and Equality in Iran) decided to boycott the election.[11]

Social media platforms created unrestricted space for discussion. The suspended candidates and political figures used Clubhouse to express their views on the election while the government banned many accounts of political figures and activists and the state-run television gagged any anti-government voice. These discussions were mainly about the future of the Iranian republic amid the political deadlock exposed in the 2021 election.[12]

Abroad, more than 200 Iranian activists living overseas, including human rights activists, academics, writers, journalists, lawyers and artists, issued a statement on June 4, 2021, to support the active boycott of the election, describing the structure of the Iranian republic as “unreformable.” Some opposition organizations and figures critical of the Iranian republic, inside and outside Iran, joined in the boycott of the election.[13]

The campaigns incited fear amongst members of the ruling class about the voter turnout rates, recalling the 2020 parliamentary elections — which had recorded the lowest voter turnout since the 1979 revolution with 42 percent. Back then, the country was facing challenges due to growing public discontent and widespread criticism over the government’s performance, holding it responsible for the harsh living conditions. As a result, a wide wave of protests erupted from 2017-2019 —including wide factional protests in 2018, which are still going on in some Iranian cities. Slogans against the political system and its religious and political figures were chanted in the protests, foremost among these, slogans against the supreme leader. Later, this discontent grew to wide-ranging campaigns to boycott the election.[14]

In response, the ruling system mobilized its supporters and took punitive measures against activists calling for a boycott. Dozens of civilians have been summoned and interrogated for several hours by the security services over the past month for allegedly publishing information urging citizens to boycott the presidential election. Further, citizens whose identification cards are not marked to vote, particularly state officials, had to face some consequences.[15]

- Aspects of Voter Turnout in the 2021 Presidential Elections

28.6 million Iranians out of 59, 310, 307 eligible voters cast their votes, i.e., the voter turnout stood at 48.8 percent. Void votes reached 3, 726,87 votes; 12.9 percent. Upon these figures, we conclude the following:

- The Lowest Voter Turnout in the History of Iran’s Presidential Elections

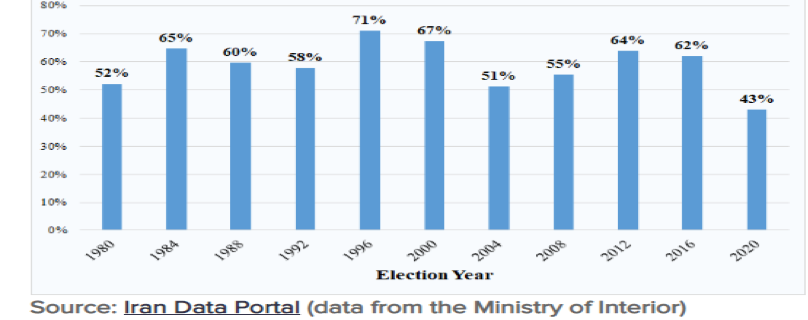

The 2021 presidential election has recorded the lowest voter turnout in Iranian elections since the 1979 revolution; for the first time it dips lower than 50 percent (see Figure 1). The level of voter turnout in 1997 was 80 percent and in 2009 was 85 percent of eligible voters. Ahmadinejad won the 2009 elections, yet doubts swirling around the election results led to the eruption of the so-called Green Movement protests. The voter turnout in the 2013 and 2017 elections was 73 percent, which Hassan Rouhani won.

Holding both presidential and local council elections at the same time should have resulted in a higher turnout rate but this did not happen. Probably, if the two elections were not carried out at the same time, the turnout would have been even lower.

Figure 1: Turnout in Iran’s Presidential Elections 1980-2021

Source: Garrett Nada, “Raisi: Election Results Explainer,” United States Institute of Peace, June 23, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3ACn1j1

- General Trends of Declining Turnout

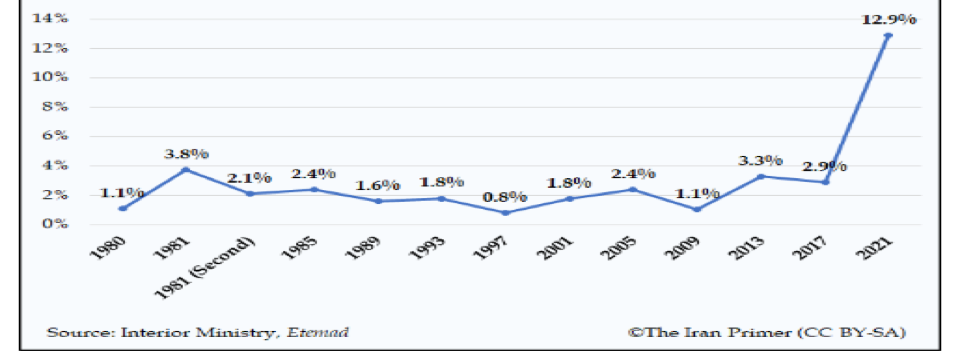

The 2020 parliamentary election had the lowest-ever turnout, reaching almost 43 percent. The highest-ever turnout in the parliamentary election was in 1996 with 71 percent, in which the “reformists” won the majority of seats. The year 2008 also reported a low turnout with 51 percent of eligible voters casting their ballots (see Figure 2). This indicates that the political system has lost its ability to mobilize, and the general reluctance of people to vote; perhaps due to the loss of trust in the election’s effectiveness. It means that the political system is facing a legitimacy crisis and a decline in popular support for its policies.

Figure 2: Turnout Amongst Eligible Voters in Parliamentary Elections ( 1980-2020)

- The Relationship Between Competition and Voter Turnout

Brazen election engineering was carried out by the Guardian Council in the 2021 presidential election to pave the way for an easy win for the candidate affiliated with the supreme leader’s current, Ebrahim Raisi. The same scenario was witnessed in the 2020 parliamentary election; the council deprived the “reformists” – including most of the 10th Parliament lawmakers – from running in the election to end up with the “hardliners” dominating the Parliament. The turnout back then reached the lowest in Iran’s parliamentary elections with 43 percent of eligible voters casting their ballots. Reviewing the elections over the past 20 years, the link between the competition (between the “hardliners” and the “reformists”) and the voter turnout rates becomes clear; in 2004 and 2007 the Guardian Council’s strict filtering of the “reformists” led to a decline in voter turnout (see Figure 2).

- Protest Votes

The election results showed an interesting phenomenon, an unprecedented increase in blank votes; many voters casted blank votes in the ballot, i.e., they did not vote for any candidate. More than 3.7 million void votes; 12.9 percent of the total vote, the Ministry of Interior reported. This percentage is triple fold of all void votes, which have been counted since 1980 (see Figure 3). This popular move is a sort of protest against the policies and procedures of elections, embarrassing the ruling elite to a great extent. It not less significant than the boycott campaign which was launched by the opposition under the slogan “I will not vote” and succeeded by making the voter turnout the lowest since 1979. The void votes posed a challenge to the supreme leader, who issued a fatwa prohibiting this form of voting.

Figure 3: Percentage of Void Votes in Presidential Elections

- Voter Turnout Decline in Urban Areas

By analyzing the ballots in major cities, it is clear that the voter turnout was less than 30 percent of eligible voters.[16] Low voter turnout in Tehran and other cities provides an indication of low turnout in urban areas where upper and middle classes live and the nature of economic and social changes Iran is witnessing. Only 3,346,580 votes out of the total 9, 815, 77 eligible voters cast ballots in Tehran Province, i.e., 34.38 percent of eligible votes in the province while voter turnout reached 26 percent in Tehran city alone and 29 percent in Tabriz.[17] The low voter turnout in urban cities might point to the fact that a wide range of the middle strata, affected by the deteriorating living conditions, gave up on supporting the political system. However, voter turnout was lower in the cities enjoying better living conditions. This is likely due to the absence of political competition, based on ideological and partisan considerations. The middle and upper classes are more interested in democratic values and criteria and ideological debates; thus, they are not interested in participating in the current political life neither in the elections which they deem non-democratic.[18] The low turnout in Tehran led to the loss of the “reformists” in the local elections as happened in the 2020 parliamentary election.

- High Voter Turnout in Rural Areas With Ethnic Groups

Voter turnout was high in rural areas where ethnic and sectarian groups live. This is due to the strong network of the political system in these areas and the influence of money in the poor areas to mobilize people. This is in addition to the local election conflicts in village and city councils, which coincided with the presidential elections. The local elections ensure that high a number of candidates’ supporters attend the elections. According to statistics released by the Ministry of Interior, more than 51,000 candidates registered their names in the local council elections and 248,000 registered in the village council elections. The high voter turnout in deprived areas, where people struggle with economic woes, is due to the religious beliefs of its citizens residing in the eastern-tribal region, who are tribally and religiously inclined.[19]

Table 1: Voter Turnout in Iranian Provinces for the 2021 Presidential Election

| Province | Turnout Percent | Province | Turnout Percent |

| South Khorasan | 74.38 | Zanjan | 53.45 |

| North Khorasan | 63.97 | Qom | 53.17 |

| Elam | 63.11 | Qazvin | 52.30 |

| Sistan and Balochistan | 62.75 | Ahvaz | 49.98 |

| Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad | 62.59 | Markazi | 48.94 |

| Golestan | 61 | Fars | 48.73 |

| Mazandaran | 60.75 | Lorestan | 48.16 |

| Kerman | 60.58 | West Azerbaijan | 44.25 |

| Bandar Bushehr | 58.73 | Hamedan | 46.48 |

| Hormozgan | 58.70 | Kermanshah | 46.04 |

| Yazd | 58.45 | East Azerbaijan | 44.25 |

| Gilan | 57.35 | Isfahan | 43.81 |

| Razavi Khorasan | 55.09 | Alborz | 41.35 |

| Ardabil | 54.38 | Kurdistan | 37.37 |

| Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari | 54.48 | Tehran | 34.39 |

| Semnan | 54.24 | Nationwide | 48.8 |

Source: “Provinces’ Participation in Presidential Elections Announced,” Khabar Online, accessed July 5, 2021, https://bit.ly/3xXvZFj

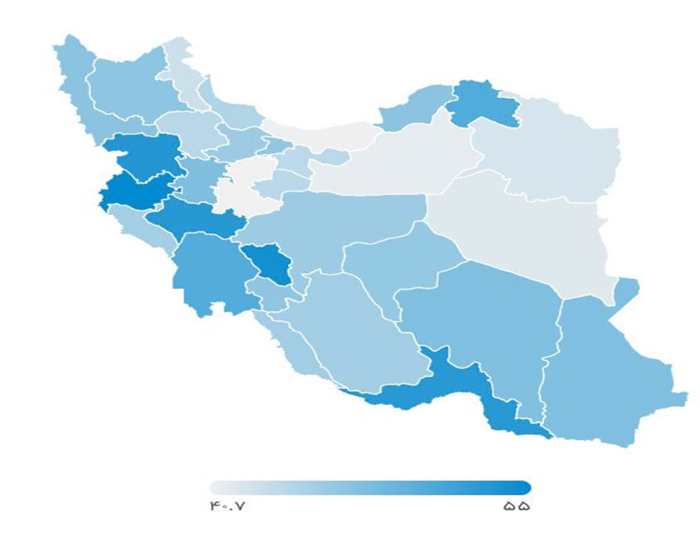

- Inverse Relationship Between Poverty and Voter Turnout

There is a strong inverse relation between voter turnout rates and the misery index. According to the Statistical Center of Iran (SCI), with regard to inflation and unemployment in 2020, the misery index exceeded 50 percent in seven provinces: Kermanshah 46.04, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari 54.48, Kurdistan 37.37, Lorestan 48.16, Hormozgan 58.70, North Khorasan 55.09, and Ahvaz 49.98. When comparing the distribution of the 2019 protest map with the misery index map, it becomes clear the strong correlation between deteriorating living conditions and the spread of protests as well as with the low voter turnout. The 2021 elections witnessed a sharp drop in comparison to the 2017 elections in the provinces ranking high on the misery index.[20]

Map 1: The Misery Index in Iran’s Provinces

Note: Dark and light blue represents low and high misery index

Source: “What Is the Relationship Between Low Voter Turnout Rates and Misery?” Iran Wire, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3depXZ5

- Reasons for Low Voter Turnout and High Protest Votes*

The low voter turnout in the 2021 election and the high number of protest votes are due to several reasons, most prominently:

- Demographic Changes and the Aspirations of the Younger Generation

According to the population census for mid-year 2021, the population of Iran is nearly 85 million; people age 18-40 years constitute 40 percent of the population and 45 percent of eligible voters, i.e., the majority of voters are young who have not experienced the Iranian revolution, neither have they been exposed to the revolutionary ideology at its peak time. The younger the voters, the more they are disappointed and discontent with the ruling system, the restrictions on personal freedoms, the Basij acting as the morality policy and repressing protests, and the banning of major social media networks. [21] The gap between the young people and the religious rulers of the system is quite wide and deep. They aspire for change and are influenced by modern global values; most of them participate in anti-government protests while others resort to immigration. Iran’s skilled, qualified and professional youth prefer to immigrate because they cannot adapt themselves to living under the cultural and religious guardianship; leading to the increase in brain drain from the country.[22]

Reviewing the latest social changes, it becomes apparent that Iranian families aspire for more modern economic and social values, which naturally conflict with the traditional vision imposed by the ruling system on society. For example, the supreme leader urges Iranians to have more children; however, the family size has declined over recent decades. Iranians have turned a deaf ear to his calls. This modernist outlook has affected the participation of this category in political life; including the elections.[23]

Table 2: Number of Voters in Iran 1980-2021

| Elections (Year) | Number of Voters |

| 2021 | 59,310,3071 |

| 2017 | 56,410,234 |

| 2013 | 50,483,192 |

| 2009 | 46,199,997 |

| 2005 | 46,786,418 |

| 2001 | 42,170,230 |

| 1997 | 36,466,487 |

| 1993 | 33,156,055 |

| 1989 | 30,139,598 |

| 1985 | 25,993,802 |

| 1981 (October) | 22,687,017 |

| 1981 (July) | 22,687,017 |

| 1980 (January) | 20,993,643 |

Source: The Iran Social Science Data Portal, accessed July 5, 2021, https://bit.ly/3qUJLX3

- Urban Growth

The Iranian people have become more urban; 75.5 percent of the population is urban as most Iranians were born and raised in big cities. This category of the population is more interested in urban management, transportation, environment and pollution, as well as in issues related to freedoms, democracy, and openness. The young people in urban cities have their own vision of life, which is extremely divergent from that of the ruling system. For example, the number of single women (20-34 years) have increased while 50 percent of young men (within the same age range) are still single. Some of them resort to the so-called mariage blanc (marriage without consummation) and cohabitation. This category of the population does not relate to strict traditional and religious values and it is very difficult to find a candidate who is able to attract them.[24]

- Women’s Voter Turnout Amid Cultural and Religious Restrictions

Women, who constitute almost half of the Iranian population, struggle with harsh realities. More than 3 million women are heads of households; their number is increasing.[25] In 2020, out of 1,000 marriages, 318 divorces were reported. According to statistics, about two decades ago, there were only 80 divorces recorded out of 1,000 marriages. This means that divorces have quadrupled in Iran;[26] amid the harsh working conditions and the rising feminist movement, which have led to a counter-wave against the ruling system to defend civil and political rights. Without a doubt, these new social trends have affected voter turnout and the voting method in the presidential election. The young people, who represent the majority of voters, reject the traditional religious elites, who deem modern developments as a threat to their stature and to the religious and traditional identity of Iran. The decrease in the population in urban areas and the melting down of the middle-upper and middle classes mean that voter turnout in elections is mainly affected by the harsh living conditions.

- The Government’s Failure and the Loss of Trust Between the People and Decision Makers

Certainly, the social and economic changes over the last decade have impacted the methods of political participation in general. Iranian society has experienced complete disappointment since the 1979 revolution and this has become a hot topic of discussion amongst a wide strata of the Iranian population. The loss of trust has been growing massively day by day amid widespread corruption and cronyism.[27] This indicates clearly that there is a wide gap between the people and the decision makers. The government has failed to meet its promises: mitigating people’s suffering, implementing its plans for equality and openness, and resolving foreign policy problems. The same loss of trust fueled the Green Movement protests which erupted following the 2009 elections and the 2017 and 2019 protests as well as many other factional protests, which are still intensively taking place in Iran until now.[28] In the second tenure of Rouhani, the working class and the youth — including students, traders and craftsmen— led large-scale protests in 2018. In the same year, laborers also protested over deteriorating economic conditions, low income, widespread corruption, the government not meeting its promises and low government performance in general, especially in addressing the COVID-19 crisis and delivering vaccines.

- Absence of Competition and Election Engineering

To facilitate authentic and democratic elections, it is necessary to ensure appropriate procedures and rules are devised when formulating policies for popular participation. Furthermore, it is important to empower citizens and protect their right to take part in political life by granting all citizens the right to compete for executive and legislative posts and allowing them to exercise their powers. This cannot be ensured without a peaceful power transition and protecting people’s right to political competition, given the fact that the people represent the source of power and the government’s mandate is basically to represent all people, i.e., it does not represent a specific person, group, or party. On the ground, there has not been an appropriate environment for voter turnout in elections. The Guardian Council refused to make key amendments in the election law to permit the holding of free and fair elections. This led to the denial of a fundamental election condition; competition. The council had excluded prominent figures such as Mostafa Tajzadeh, a “reformist” politician. It not only excluded prominent “moderates” and “reformists” from the presidential race but also outstanding “conservative” figures such as Ali Larijani, the former Parliament speaker. Since then, it has become apparent to most observers that the “hardliners” loyal to Ali Khamenei who constitute the so-called “hardcore of power” had been working to make Raisi win the election at any cost.[29] According to a survey conducted by the Group for Analyzing and Measuring Attitudes in Iran (GAMAAN), some respondents explained that their main reason for boycotting the election was the Guardian Council’s disqualification of their preferred candidate.[30] The election’s competitiveness was fragile and the ideological polarization was blurred because all candidates were maneuvering under a ceiling that cannot be exceeded. Elections are a process through which divergent political trends or attitudes are chosen; this cannot be implemented in Iran under a ruling system based on Velayat-e Faqih.[31]

- Loss of Trust in the Ability to Influence Political Decision Making

Election engineering has made the Iranian people lose confidence in their ability to influence political decision making in their country. The ruling system imposes its own electoral structure as a fait accompli. The people do not have any influence over choosing their representatives, so, accordingly, they cannot influence decision making in respect of domestic and foreign policies. The latest changes in the political system have revealed the marginality of the Iranian presidency. The president does not have power to implement any “reformist” agenda/plan at home, neither can he take a foreign policy decision without receiving direct orders from the supreme leader and the Revolutionary Guards. This was apparent during the tenures of former Iranian Presidents Khatami, Ahmadinejad and Rouhani; back then, some state institutions were intensively and clearly operating out of the government’s control such as the Revolutionary Guards.[32]

- Fragile Partisan Structure and Absence of Programs

The partisan structure in Iran is weak and fragile; elections have been mainly based on the person not on the program by nominating influential and popular figures.[33] Thus, the programs of election candidates were not realistic or practical and the candidates could not convince voters about the effectiveness of their programs.[34] Most candidates did not present any alternatives or clear frameworks for solving economic dilemmas. They resorted to explain the dilemma itself, instead of proposing effective solutions. For example, a candidate during his campaign listed the country’s economic woes instead of illustrating the deeply rooted reasons for these problems.[35] Thus, people’s expectations for effective future economic reform and for candidates meeting their campaign promises declined.[36] Voters, through the passage of time, have become pessimistic about the benefits and effectiveness of elections. This was apparent in their views and actions in the latest presidential election.

- The Government’s Failure to Address the COVID-19 Pandemic

Concerns have been rising over the spread of the COVID-19 virus in Iran, taking into account that the Iranian government failed to address the crisis from the very beginning. It had also hidden the extent of the pandemic’s spread from the beginning to ensure large-scale voter turnout in the 2020 parliamentary election. Data about the spread of COVID-19 in Iran is not transparent and authentic. This is probably the reason behind some people’s refusal to vote.

- Consequences of Low Voter Turnout

The low voter turnout in the 2021 presidential election exposed a serious crisis that the Iranian political system has been experiencing. The dimensions of this crisis can be explained as follows:

- Growing Disappointment and the Erosion of Legitimacy

The Iranian people feel that they do not effectively partake in political decision making; their opinions are not considered. It is common knowledge that weakening legitimacy often leads to popular discontent and outrage. This legitimacy deficiency has translated into rebellions and protests against the state; over the course of 40 years. Iran has witnessed several cycles of protests and revolts starting from minority revolts in the early 1980s; the student protests in 1999; the 2009 presidential election protests; the 2017 protests; the 2019 fuel protests; and the violent protests against the government in economically and politically marginalized regions of the country. The length of time between major protest waves has dramatically shortened in recent years, indicating that the Iran’s political system’s legitimacy have eroded further. Factional protests have risen noticeably, reflecting various dimensions of the legitimacy crisis facing Iran’s political system as these protests represent an array of political, economic, and social groups.

- Decline in the Social Capital of the “Reformists”

With the disinclination of voters to participate, the “hardliners” made a ruthless grab for power and have excluded the “reformists” completely. The latter failed to present themselves as a suitable political alternative, or as effective political opposition. Schisms within the “reformists” have grown unprecedentedly. They failed to implement major reforms needed to safeguard their grassroots support. Their position has revealed that they have become part of the ruling system; granting it the legitimacy needed through creating a veneer of political competition. Faezeh Hashemi Rafsanjani, daughter of the former late Iranian president, explained why she would not vote in the presidential election, saying that the candidates are from the political system and are part of the status quo. She added that the performance of the “reformists” triggered her not to vote.[37] Apparently, the popular mood has shifted strongly, not solely against the “hardliners” but also against the “reformists.”[38] But the phenomenon of blank votes, i.e., ballots not filled out but cast, drew great attention because they indicated that multiple segments in Iranian society do not believe in the framework of the existing political process, yet they are keen to partake in political life beyond the traditional conflict between the “conservatives” and the “reformists.”[39]

- Decline in the Political System’s Support Network and Revolutionary Rhetoric

The decline in the political system’s grassroots support has become blatantly evident. The system, perhaps, has lost its appeal; the role of seminaries has shrunk as the revolutionary and theocratic ideologies have started to fade. Though the theocratic establishment monopolizes sources of income, its popular support has shrunk, particularly among the urban youth. High-ranking clerics complain about the decline of religious zest in the youth, wringing their hands over a significant decline in the number of youth volunteering to partake in their organizations. Though the system has repeatedly underpinned the significance of voter participation in the election, the Iranian people turned a deaf ear. The narrative to encourage a high voter turnout stressed supporting the Iranian republic and countering the West. The low voter turnout indicates that this narrative is no longer effective in mobilizing the Iranian people.

- The Schisms Within Iranian Society and the Expansion of Internal Opposition

Approximately 50 percent of eligible voters boycotted the election, in addition to 13 percent of voters who casted blank votes as a form of protest. The supreme leader argued that the protest voters are supporters of the system in an attempt to hide the expanding opposition and protests against the political system. The foregoing was crystally evident during the 2021 presidential election. On the ground, the scope of internal opposition has been expanding steadily due to the simmering public outrage in recent years. This will most likely have ramifications if the internal crises remain unresolved, particularly the economic crisis. If the ruling system fails to mitigate the deteriorating conditions , a new wave of protests against the whole political system is highly expected to erupt.[40]

- Resorting to Protests as Forms of Political Participation and Expression

Amid a lingering political impasse as their voices were not heard by Iranian decision makers, the Iranian people resorted to protests including non-political, non-traditional and sometimes illegal activities to snatch economic and political privileges from the system. Iran, in recent years, has witnessed multiple forms of agitation: demonstrations, factional protests, and writings on public walls. Some movements resorted to armed resistance due to the spread of unemployment, rising inflation and deteriorating living conditions, which may worsen further under the new President Ebrahim Raisi – given his militant policies towards the West, which will probably mean the continuation of UN sanctions against Iran and its international isolation. Large-scale protests erupted in the country in June and July in 2021 due to the harsh economic conditions; most prominently over the worsening water and power crises as well as other protests held by oil workers over their working conditions. So far, the Iranian authorities seem to be containing this wave, yet the simmering popular outrage following Raisi’s ascent to power, somehow, is similar to the popular discontent which erupted against the Shah of Iran Reza Pahlavi.[41] Both came to power with low popular support amid public resentment over widespread corruption in decision-making circles, coercive power, and extensive international opposition.

- Absence of Accountability and the Lack of Popular Support for Decision Makers

The low voter turnout along with the protest votes means that the legitimacy of the sitting President Ebrahem Raisi is uncertain while his loyalty will remain with the supreme leader of the ruling system who granted him the position. He will not be held accountable before the Iranian people, i.e., he will simply implement the supreme leader’s orders without paying attention to public opinion. Raisi is not viewed as a representative of the Iranian people rather he is seen as a follower of the supreme leader, a loyal soldier of the ruling system. This will be clearly apparent through the domestic and foreign policies that he will pursue. .

At home, Raisi will not counter the rampant corruption within the ruling system. Forbes reported that the number of Iranian billionaires, who are above reproach, has increased while the number of poor people has dramatically risen amid the complete absence of justice.[42] It seems that the political system benefits from sanctions and the economic crisis. Raisi will not address the IRGC’s hegemony over the country’s economy. Abroad, Raisi will also be committed to the supreme leader’s approach, allowing further guardianship over the government from parallel institutions (operating under the supreme leader) such as the Supreme National Security Council and the IRGC. He will not respond to the public demand to halt the ruling elite’s foreign interference and its funding of Iran’s expansionist project. Raisi is expected to mainly focus on tackling the economic crisis through reviving the nuclear deal while maintaining the existing pillars of Iran’s foreign policy — enmity, nationalism, independence, and regional hegemony. For the first time, the Iranian government because of a low voter turnout in the 2021 election will lose its ability to speak on behalf of the people to the outside world, recalling here the remarks of Mohammed Javad Zarif, Iran’s former foreign minister, who said “I am a minister of a country where 73 percent of its people turn out to cast their ballots in the elections.”[43]

- The Widening Gap Between the Ruling System and the Younger Generation

Since they are perceived as unfair, Iranian elections have not mobilized the Iranian people nor achieved high voter turnouts. Due to exclusionary tactics, new political actors have not had the opportunity to exercise political power – despite the efforts to bring in new faces and orchestrate competition between the “reformists” and the “conservatives” to make the elections seem authentic. Thus, Iran has not witnessed significant changes in its political pyramid for 40 years; no new figures have been able to secure influential positions, nor have they participated effectively in policy making. The ruling system has controlled elections through nominating and ensuring the victory of its supporters. It has manipulated election rules at every stage: nomination, voting, ballot counting, and announcement of results. This is to maintain the status quo; to keep the Iranian people governed by the same religious elites for longer. As a result, the Iranians, including the young people, have been denied their right to effectively participate in internal politics. This has been done to prevent new political actors from emerging and gaining power.

- Opportunities for Political Transition in the Post-Khamenei Period

The results of the 2021 presidential election show that the system is keen to maintain a coherent and integrated power structure in which the “reformists” and the “moderates” take high ranking positions. Furthermore, many traditional “conservatives” like Ali Larijani have been marginalized, i.e., excluded from power. The main reason for the current election policies, according to some observers, is that the political system is preparing for a potential transition of power with a new supreme leader taking Khamenei’s position after his death. Although the “hardliners’” ruthlessly grabbing power and dominating the three branches of government may reduce their fears about the post-Khamenei era in the long run, their thirst for power may generate serious challenges in the short run. The ruling system may face further internal schisms; former President Ahmadinejad now leads an influential current inside the system. Ahmadinejad scathingly criticized the supreme leader as the latter deemed the election a great victory, saying, “Could it be more laughable to call this a great victory?” He added, “They put aside the people [in the election] and are trying to explain it away.” Referring to Khamenei, Ahmadinejad remarked that this is “a pity for him.” [44] The “hardliners” had held the “moderate” President Rouhani responsible for all the country’s social and economic problems. However, if the “hardliners” led by Raisi fail to address the country’s problems, their legitimacy will deteriorate to a great extent, impacting the smooth transition of power in the post-Khamenei era.

Conclusion

According to the late Samuel Huntington, a longtime Harvard University professor, elections – including voter turnout – are considered to be forms of political activity to influence decision-making. In addition, political activity requires legal rules and protocols to create an effective environment for political participation; the Iranian people lack the latter. The nature of the theocratic ruling system; its ideology based on the theory of Velayat-e Faqih, does not take public opinion into consideration not only in jurisprudential issues but also in all walks of life. Velayat-e Faqih advocates a guardianship political model, assigning the supreme leader as the guardian of society.

On the ground, the Iranian ruling system undertakes various actions to undermine the will of people; the disqualification of candidates carried out by the Guardian Council is an example of this. Through this process, the system paves the way for its loyal candidate to be victorious without the need to engage in election fraud. This measure was probably effective in the 2017 presidential election. However, the unprecedented large-scale boycotting campaign and protest votes during the 2021 election sent direct messages to Iran’s religious leaders, particularly to Khamenei and Raisi, and to the whole ruling class that “we are not with you” or “ we are so sick of this game.”

The ruling system is inflexible and does not intend to respond to the huge social changes and is still determined to maintain its policies, and militant rhetoric, as well as keep in place revolutionary loyalists. This, as a result, widens the gap between the Iranian people and the ruling system, which will continue facing a legitimacy crisis, which will grow over time. The system will probably face a popular revolt like that of the 1979 revolution.

[1 “Yazd’s MP: the enemy is after decreasing people’s turnout in the election”, IRNA, June 7, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/2SXAK2C. [Persian].

[2] Bobby Ghosh, “Iran’s Election Is All About Supreme Leader’s Toxic Legacy,” Bloomberg, June 15, 2021, accessed July 7,2021, https://bloom.bg/3jYOBRw

[3] “Representative of the Supreme Leader in the IRGC: We want the president to be a pure soldier to the country,” Asr Iran, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3potwAO. [Persian].

[4] “The nation will bring honour to the country and the system with its presence,” The Office of the Supreme Leader, June 16, 2021, accessed August 9, 2021, https://bit.ly/3AqcSoS.

[5 Reza Naqdi: Iran’s 2021 Presidential Elections: Calls for Non-Participation in Elections Seek to Destroy Iran,” Fars News Agency, June 5, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3pnmGLS. [Persian].

[6] “Ahmad Khatami: Voting is a “yes” vote to the Islamic Republic / Those who failed to say “yes” to this system at the beginning of the revolution June 18 is the day of their re-allegiance to the regime,” Entekhab, June 2, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3wUSA55.[Persian].

[7] “Sunni Friday Imam of Bandar Abbas: We call on the leader of the revolution to participate as much as possible/ Government should use the capacity of the Sunni elite,” Tasnim News Agency, 3 June, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3uJC4TN. [Persian].

[8] “Calls of the General Staff of the Armed Forces to the people to turn out in the elections,” ISNA, June 17, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3cOXn07. [Persian].

[9] “Karroubi condemns “illegal interference” in 1400 (2021) elections,” Radio Farda, June 3, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/34K0ORx. [Persian].

[10] “Iran’s presidential election: Who boycotts it and what is its significance? BBC, June 16, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bbc.in/3xobjGO. [Arabic].

[11] Ibid.

[12] Golnaz Esfandiari, “With Much of Debate Hampered Ahead Of Presidential Vote, Iranians Turn To Clubhouse – Analysis, Eurasia review,” Radio Farda June 15, 2021, accessed on 08 July 2021, https://bit.ly/3APe59u. [Persian].

[13] “More than 200 activists outside Iran call for boycott of presidential election,” Radio Farda, June 5, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3puL6mU. [Persian]

[14] “Campaign ‘No Islamic Republic in Iran.’ Expands on the anniversary of the ‘referendum on order,’” Iran International, April 10, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3wn7f8r.

[15] “Iran’s presidential election: Who boycotts it and what is its significance?

[16] Amir Bar Shalom, “The Unwritten Agreement between Israel and Iran,” Times of Israel, July 4, 2021, accessed July 5, 2021, https://bit.ly/2V6VWEh. [Hebron].

[17] “The enemy spent a lot of money to influence the recent elections in Iran,” Tasnim News Agency, July 18, 2021, accessed July 25, 2021, https://bit.ly/3x0UCA9. [Persian].

[18] “Rouhani: We mustn’t sacrifice the lofty goals of the system for the sake of elections,” Tasnim News Agency, June 23, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3qwkbaV. [Persian].

[19] “Causes of low voter turnout,” Aftab Yazd, June 26, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3vVtLoM. [Persian].

[20]Ali Razipour “What is the relationship between low voter turnout rates and misery? IranWire, July 13, 2021, accessed July 14, 2021, ، https://bit.ly/3depXZ5. [Persian].

[21] Akram Alfy, “The rhetoric of the Iranian elections,” Ahram Online, 10 Jun 2021, accessed July, 07 2021, https://bit.ly/3yr4Zyc .

[22] “Candidates are far away from the people,” Aftab Yazd (cited in Pishkhan) June 10, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3vaiVdW. [Persian].

[23] “Parliamentary Research Center – Iran’s Birth Rates Continue to Decline,” Jadeh Iran, November 15, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3qPWtXf. [Arabic].

[24] “What is the story of the controversial ‘mariage blanc’ in Iran?” BBC, July 15, 2019, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bbc.in/3AFG10i. [Arabic].

[25] “The Suffering of Iranian Women Under Valayet-e Faqih,” Marsad.Ecsstudies, January 2020, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3AEueyY. [Arabic].

[26] “Iran’s divorce rate hits record high,” Iran International, July 4, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3wlGykr. [Arabic].

[27] “Why is social participation declining in Iran?,” Jameh24, July 2, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, accessed July 9, 2021, https://bit.ly/3dya9R4. [Persian].

[28] Bijan Khajehpour, Iran’s Youth Key to Elections,” Al-Monitor, May 31, 2013, Accessed 7 July 2021, https://bit.ly/3yv5veH .

[29] Hamidreza Azizi, “Iran’s presidential election: three key implications,” Mena Affairs, 24 June 2020, accessed 07 Jul 2021, https://bit.ly/3vZsexU .

[30] Pooyan Tamimi Arab and Ammar Maleki, Why Iranians won’t vote: new survey reveals massive political disenchantment, The Conversation, June 10, 2021, accessed 07 Jul 2021, https://bit.ly/3dRfUcQ .

[31] “Why the names of Abbas Bouzar and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad were written in the ballots? Khabaronline, June 23, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/35LBH17. [Persian].

[32] Jalal Khoshchehreh “The difficulty of crossing the wall of people’s distrust,” Ebtekar News, July 7, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/34VyY4X. [Persian].

[33] “Hashemi: Reforms need new blood,” ISNA, June 28, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3wWRrdA. [Persian].

[34] “Correcting the election culture,” Jomhouri-e Eslami, June 26, 2021,accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3wWRrdA. [Persian].

[35] “Ignoring seven key issues: Why didn’t the candidates’ “difference in perspectives” become clear? Donya-e-Eqtesad, June 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3gdqb3m. [Persian].

[36] Abas Arkon, “Mechanisms needed to meet promises,” Tejarat Newspaper, June 9, 2021, accessed July 8, 2021, https://bit.ly/3x79Cgu. [Persian].

[37] “Faezeh Hashemi: The reason I didn’t vote is mostly the performance of the reformists,” Bultan News, June 18, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3wPuMQB.

[38] Khatami: Low voter turnout is a sign of the people’s dismay,” Radio Farda, June 21, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/35LqJZi. [Persian].

[39] “ The 2021 election phenomenon: Who are casting invalid votes?” Khabar Online, June 21, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3cX51G5. [Persian].

[40] Jon Gamrell, “Analysis: Subdued Iran Vote Will Still Impact Wider Mideast,” The Associated Press, June 15, 2021, accessed July 8, 2021, Https://Bit.Ly/3adylgx .

[41] In 1976, Iran witnessed blackout across different regions, which erupted wide-scale discontent. Opponents to the Pahlavi ruling system seized the crisis, wrote anti-Shah slogans and launched protests. See, Ali Salehabadi, “Why the country regressed instead of progressing, what is the root cause? Setaresob Online, July 10, 2021, accessed July 10, 2021, https://bit.ly/3yHvm37. [Persian].

[42] “Confronting big shots is prerequisite for economic reform”, Tejarat Newspaper, July 8, 2021, accessed July 7, 2021, https://bit.ly/3h47hh4. [Persian].

[43] Ali Salehabadi, “Why did JCPOA go into a limbo?” Setareh Sobh Newspaper, July 9, 2021, https://bit.ly/3jCVTdG

[44] “In New Video, Ahmadinejad Criticizes Iran’s Khamenei,” Iran International, July 2, 2021, accessed August 16, 2021, https://bit.ly/3jSKPHU.