Introduction

The nuclear deal has been a turning point in the course of Iranian-European relations. The governments of the European Troika (France, Germany and the UK) and their Iranian counterpart contributed significantly to concluding the agreement and reaching common ground. This was done in order for both parties to reap the political and economic benefits from lifting the UN sanctions on Iran. This was in addition to monitoring Iran’s nuclear program. When the Trump administration decided to pull out of the nuclear deal, the European parties clung to the deal and adopted a neutral position with regard to the recriminations between the two parties (the United States and Iran) to prevent the total collapse of the deal.

The policies of Russia and China clash with those of the United States. As a result, they denounced the US pullout from the deal and rejected the sanctions imposed on Iran. Along with Iranian diplomatic efforts, the three parties seek to persuade the European countries to adopt a position which is in opposition to Trump’s unilateral policies. On the other hand, the United States is exerting significant efforts to influence the Europeans so that they abandon the nuclear deal. The United States points to Iran’s continuous breaches of the nuclear deal and its threat to maritime navigation and regional stability. Iran commits these breaches as a blackmailing tactic. The United States has also warned of the mounting Iranian missile threat. As for the consequences of the political and diplomatic standoff between Iran, Russia and China on one side, and the United States on the other, the European position on the deal has become the fundamental basis which all the signatories depend on, ensuring the future of the deal.

On January 14, 2020, the European Troika decided to opt to activate the deal’s dispute settlement mechanism (DRM). This development came after Iran revealed the fifth step in its series of nuclear violations. Iran began doing so on May 8, 2019, announcing that it would no longer abide by the restrictions placed on uranium enrichment. This escalation represents the biggest threat to the future of the nuclear deal as it contradicts the efforts by the two parties to uphold the deal.

Despite Germany carrying out the first INSTEX transaction for humanitarian purposes in April 2020, the debate that arose was about the Europeans possibly continuing with INSTEX transactions while facing tremendous US pressures. This time the pressure is aimed at extending the arms embargo imposed on Iran scheduled to expire in October 2020. This lifting of the arms embargo is in accordance with the nuclear deal signed between Iran and the P 5+1 in 2015. The Europeans harshly criticized Iran for launching a satellite into space. They considered this move as a prelude to Iran developing its ballistic missile program, which is extremely concerning for the European parties.

Undoubtedly, there are a host of strategic and vital interests that govern the relationship between Iran and Europe, such as political interests emerging from their respective regional and global positions and scopes of influence. This is in addition to the political relationships between the two sides in regard to areas of conflict and mutual influence, especially the Gulf region, as well as European economic gains after the signing of the nuclear deal. This is in addition to Europe’s economic interests in the entire region and Iran’s role in influencing the flow of strategic commodities to Europe and the world, as well as European strategic and security interests, as Iran is an influential regional power impacting the security and stability of the region. The Iran nuclear deal has been of great importance since its signing for both the Europeans and Iran. It has become the most important factor affecting their mutual relations as it is considered a vital strategic and security interest. This is probably the reason for their eagerness to uphold the deal despite the US withdrawal on May 7, 2018 and the continual pressure imposed on both sides by the Trump administration to force them to withdraw from it.

This study assesses the hypothesis that common interests between Iran and the Europeans led them to sign the nuclear deal and uphold it. Thus, if these common interests are no longer present, the Europeans are likely to change their position on the deal. They might trigger the DRM. According to the hypothesis, the study is structured as follows:

I. European and Iranian Motives for Signing the Nuclear Deal

II. The US Withdrawal and the European Pledges to Maintain the Deal

III. The Factors Causing a Shift in the European Position on Iran

IV. The Diminishing Importance of the Nuclear Deal

V. The European Position and the Future of the Nuclear Deal

I. European and Iranian Motives for Signing the Nuclear Deal

The nuclear deal is significant for Iran and the Europeans because it serves their mutual interests:

1- The Significance of the Nuclear Deal for the Europeans

According to the European viewpoint, the nuclear deal is of utmost significance as it aims to resolve one of the most long-standing and dangerous nuclear proliferation crises in the Middle East, thereby preventing regional countries from engaging in a nuclear arms race.[1] Through implementing the restrictions and provisions set out in the agreement, the Europeans aim to delay the possibility of Iran developing a nuclear weapon via hindering its ability to produce fissile material at its declared nuclear facilities.[2]

The European Union had four major goals in concluding the Iran nuclear deal:

- ensure the security of the Gulf sates; the largest and most important energy producers that control/maintain a balance in global oil trade;

- defuse regional conflicts to protect Europe from new waves of immigration — following the immigration wave resulting from the Syrian crisis — and further terrorist attacks;

- diversify European energy sources to reduce depedence on Russia;

- and enhance European exports, especially industrial commodities by expanding the scope of economic partnership with Iran as it represents a golden opportunity for European firms, taking into account that US firms have gained the lion’s share of investment opportunities in the Middle East.[3]

However, the Iranian missile program, posing a danger to the European territories, had not been included in the nuclear deal. Perhaps this is attributed to European considerations and the policy of former US President Barack Obama, which was based on the premise that integrating the Iranian economy with its Western counterparts is instrumental in encouraging the Iranian government to adopt more moderate behavior. Therefore, this could lead to a harmonious relationship between Iran and Europe.[4]

Gérard Araud, the French negotiator involved in the Iranian nuclear negotiations between 2006-2009,[5] said that the reason for not including Iran’s missile program in the nuclear deal was because it was important to address the nuclear crisis separately from the other files. There are agreed upon opinions and shared visions among the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council in addition to Germany.

By reviewing the history of the European desire to open up towards Iran politically and economically, we find that one of the most important European motives was their desire to play a pivotal role internationally, competing head-to-head with US hegemony — which has been increasing since the Cold War and after the collapse of the Soviet Union. This explains the European insistence on not allowing the United States to unilaterally tackle regional crises and consequently reap investment opportunities.[6]

Economically, European financial companies welcomed the nuclear deal, considering it the most “lucrative economic bonanza” for Europe since the collapse of the Soviet Union. The then-German Minister for Economic Affairs and Energy Sigmar Gabriel visited Iran on May 14, 2015, immediately after announcing the nuclear deal. Heading a large delegation of businessmen and commercial sector affiliates, the minister aimed to conclude investment contracts with the Iranian side. The French Foreign Minister Laurent Fabius visited Tehran two weeks after the signing of the nuclear deal for the same purpose. Britain also sent a delegation of 300 businessmen to Tehran in August 2015.[7]

Apparently, the resumption of political and economic connections with Iran was explained in the public sphere by Germany in particular and Europe in general as part of a policy to change Iran’s behavior via trade and rapprochement (CTTR) — this resulted in the resumption of ties which were immune from any objective appraisal.[8]

2- The Importance of the Nuclear Deal for Iran

As for Iran, the nuclear deal saved it from sanctions, blockade and isolation which it had been enduring since the presidency of Ahmadinejad from 2005 to 2013. Iran adopted a confrontational approach towards the international community; it abstained from negotiations after the United Nations imposed sanctions on its economy, including its financial system. These sanctions were issued through nine resolutions by the UN Security Council. This is in addition to a 10th resolution issued in 2013 and an 11th resolution issued in 2014, as well as 13 unilateral sanctions imposed by the United States and the European Union during the same period.[9]

The United Nations and the United States had placed an almost total economic embargo on Iran. It had a catastrophic impact on Iran’s economy and targeted its trade exchange with the world. The economic embargo froze its assets overseas and suspended its financial transactions with international banks. Its oil exports, constituting 80 percent of government revenues in 2012, had been restricted. In 2011, Iran was exporting 2.5 million barrels of oil per day (bpd). The figure declined to 1.2 million bpd in 2012 due to tightening UN sanctions.[10] The economic embargo resulted in the Iranian economy suffering huge losses, and a decline in the value of the national currency — it lost two thirds of its value against the dollar since the tightening of sanctions in 2011. The inflation rate rose to 40 percent amid a rise in the price of edibles and fuel, leading to a decline in gross domestic production by 20 percent and the unemployment rate increased to 10.3 percent.[11]

There is no doubt that the harsh economic sanctions during that period were the main trigger for Iran to sit down at the negotiating table. They forced the Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei to accept and support the Rouhani government’s policies. It intended to negotiate with the P5+1. At that time, Iran began negotiations from a relatively weaker position. But the outcomes of the nuclear deal helped Iran turn its nuclear program into a bargaining chip, reaping more political, economic, and regional gains.

During the nuclear negotiations, Iranian diplomats sought to achieve a complicated series of strategic objectives. These included, first, convincing the world that their country is working in accordance with its right to develop civilian nuclear technology.

Second, they sought to show the government’s diplomatic skills in handling sensitive issues. Third, they focused on highlighting the differences between Iran and countries that had been in conflict with the international community over developing nuclear capabilities such as Libya and North Korea. This is in addition to highlighting that Iran is a strong regional actor and a modern state that respects international laws. Finally, they sought to ensure that making concessions under the nuclear deal will lead in the end to the flow of Western investments into Iran.

At home, the nuclear issue was important as it allowed the government to mitigate the legitimacy crisis which it had been facing since the 2009 Green Movement.[12]

According to the Iranian nuclear program, conflicts between Iranian nuclear scientists had been instrumental in pushing the government to open up to the world. The scientists required sophisticated technology to develop Iran’s nuclear program. The conflict deepened further reaching the main apparatus of the country’s nuclear program; the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI).

There are two opposing views with regard to Iran’s nuclear program, represented by the positions of Ali Akbar Salehi and Fereydoon Abbasi. One needs to study their respective positions to understand better the debate that erupted between Iranian nuclear scientists. The debate was reviewed by Ray Takeyh, Iranian-American Middle East scholar, and published in the National Review.[13]Abbasi, led the AEOI at different times. Takeyeh said that Abbasi “believed that Iran must continuously expand its nuclear capacity, even if that meant relying on primitive technologies. He kept adding vintage IR-1 centrifuges to Iran’s growing stock of machines and talked about enriching uranium at ever-higher levels. In the firebrand Ahmadinejad, Abbasi found the ideal patron, a president whose truculence required an expanding nuclear program.” Afterwards, the two attempted, through the powers granted to them, to enrich uranium at high levels with the aim of reaching the threshold of making a nuclear bomb.

On the contrary, the opposite team believed that the plan pursued by Abbasi was fragile as the facilities established to achieve the plan elicited international attention and were vulnerable to US or Israeli strikes, given the sharp mounting condemnation by the UN. When President Rouhani came to power, Ali Akbar Salehi oversaw the AEOI. He defended the nuclear deal, which curbs the enrichment of uranium for a certain period but gives Iran an opportunity to have a program for nuclear development and research. Moreover, it enables Iran to renovate its nuclear infrastructure and renew the centrifuges used to enrich uranium that are capable of producing a nuclear bomb. The aforementioned will happen with more efficiency as soon as the time comes to lift the restrictions on Iran’s nuclear activities under the nuclear deal.

A genius physicist and an expert in the field of nuclear energy, Salehi played an important role in convincing Khamenei to accept the nuclear deal given his position within the supreme leader’s inner circle of trusted advisers. The Iranian government saw the agreement as an opportunity to maintain Iran’s nuclear capabilities at a certain level to meet the country’s peaceful energy needs and satisfy its aspirations of nuclear research and development. “Through this agreement, we have paved the way for the country’s speedy development in the research field and for the progress of peaceful nuclear science,” Rouhani said.[14]

In a nutshell, we could say that both European and Iranian vital interests were shaped under the nuclear deal. Some of these are security interests represented in stopping a nuclear arms race in the region. There are also economic interests resulting from opening the Iranian market to European investments in exchange for lifting the sanctions which impacted Iran’s economic situation and posed a threat to the stability of the government.

This is in addition to the political interests represented in ushering in a new relationship with the West, integrating Iran into the international community and attempting to change the behavior of its political system and countering its threats. Iran also aims to develop its nuclear program to keep pace with international advancements in modern nuclear technologies, enabling it to evade regional and global monitoring and surveillance, and legitimizing its nuclear program.

II. The US Withdrawal and the European Pledges to Maintain the Nuclear Deal

After entering the White House, the administration of US President Donald Trump opted to pull out of the nuclear deal. The administration considered the nuclear deal, or what is known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), signed between Iran and the P 5+1, to be disastrous for several reasons. The administration said the deal maintained the nuclear capabilities of Iran when it comes to enriching uranium. The deal only curbed the level of enrichment instead of guaranteeing the elimination of this danger. Iran will continue to pose a danger due to the sunset clauses set out in the nuclear deal. As the period for these clauses expires, Iran will be relieved of the obligations stipulated in the agreement. For example, in October 2020, the ban imposed by the UN on Iran when it comes to the import and export of weapons will be lifted.[15]

In 2023, the ban imposed by the UN on Iran with regard to assisting Iran in its ballistic missile program will expire.[16]

In 2028, Iran will be capable of resuming the manufacture of advanced centrifuges. In 2026, most of the restrictions stipulated in the nuclear deal will be lifted. Five years afterwards, all restrictions will be completely lifted.[17]

In addition to the foregoing, suspicions surround the sincerity of Iran’s cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Also, the Iranian ballistic missile program is not included in the JCPOA[18] though Iranian missiles are deemed as a threat, not only to the security of the countries in the region, but also to the security of the European countries.

Finally, via signing the JCPOA and lifting the sanctions, it has become possible for the Iranian government to gradually secure $130 billion[19]of frozen Iranian assets. The main point here is that this huge sum of money was used to finance the terrorist operations of the IRGC and its proxies in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen. Access to these funds allowed Iran to continue with the implementation of its expansionist strategy and its illegitimate intervention in the affairs and policies of the countries in the region.

Although the European parties had reservations about Iranian regional behavior and the development of the ballistic missile program, they continued to deem the nuclear deal as important, a common vital interest between the two sides and the best available means to address the nuclear issue with Iran. Therefore, the European parties did not opt to withdraw from the nuclear deal, but European policy inclined to maintain the deal, as illustrated through the following:

1- Keeping Open the Channels of Understanding and Coordination With Iran

The European parties betted on the survival of the nuclear deal due to its international legitimacy and the testimony of the IAEA that the nuclear deal achieves the objective of curbing Iran’s nuclear ambitions and reduces the chances of transforming it into a program for military purposes.

Based on the aforementioned, and according to the outcomes of a previous ministerial meeting held in 2018[20] which included representatives of the European Union, the European Troika and Iran, the European Troika and the European Union pledged to offer sufficient guarantees to Iran in order to keep the deal in place. On top of these guarantees come: protecting the sale of oil from US sanctions, continuing to purchase Iranian crude oil, and European banks’ committing to ensuring trade with Iran.

The European enthusiasm represented in guarantees and promises did not last long. The beginning of 2019 resulted in a new European position taking shape. It was specifically revealed in the statement issued by the European Union on February 4, 2019[21] which referred to European concerns about Iran’s missile program, regional meddling, and commitment to pledges stipulated in the nuclear deal, and suspending Iran’s hostile activities in some European capitals. The Europeans have implementing a carrot and stick policy, with the financial channel INSTEX connected to the Iranian government’s agreement to all the regulations of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).[22]

Between the shift in the European position and the Iranian threat to breach commitments under the nuclear deal and resume uranium enrichment, the European Union countries, especially the European Troika countries which are signatories to the nuclear deal, were keen to continue cooperation with the Iranian government.

The aim is to keep the channels of understanding open. The manifestations of this cooperation appeared in the meetings of the joint commission of the JCPOA which were held in 2019, during different periods, until March 2002.

2- Setting up Financial Exchange Channel INSTEX

In September 2018, the former European Union foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini announced a new Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV),[23] or what could be called a financial channel with multiple purposes. It aimed to maintain trade dealings with Iran in accordance with European laws without being hit by US sanctions. The European Union, in its meeting on January 28, 2019,[24] failed to reach a consensus on the announcement of the SPV.

Therefore, the European Troika countries found no way but to announce a “financial mechanism to support commercial exchange” known as INSTEX. France, Germany and the UK announced on the sidelines of the meeting of European foreign ministers in Bucharest[25] on January 31, 2019 the launch of INSTEX to continue trade with Iran, initially confining it to food and medicine transactions.

For INSTEX to succeed, the European Troika countries sought to get official consent from all the European Union’s 28 countries. Although there has been no supportive response since the statement for launching the financial mechanism was made, six European countries (Denmark, the Netherlands, Finland, Norway, Sweden and Belgium), announced in a joint statement on November 29, 2019,[26] that they would be joining the financial mechanism, enhancing the position of the founding countries.

The year 2019 ended with INSTEX not being implemented for different reasons which prevented both parties from moving ahead with their procedures. For its part, Iran does not accept the conditions of the FATF and does not deem INSTEX as an outlet which would prevent its economy from collapsing. As for the Europeans, they cannot force the firms working under the umbrella of the European Union to conduct dealings with Iran via the mechanism, which makes them subject to US sanctions. They also do not have the ability to undermine the decisions of the US administration by including the Iranian oil sector in the transactions conducted via the financial mechanism.

3- Supporting the Mediation Efforts Between the US and Iran

Due to the mounting tensions in the Arabian Gulf, and Iran’s announcement that it plans to reduce its nuclear commitments, France delegated Emmanuel Bonne, adviser to French President Emanuel Macron, to Tehran for the second time to submit his proposal for a “mutual freeze.”[27] This means that sanctions would be halted and in return Iran would stop the reduction of its nuclear commitments.

The Iranians expressed a “vague” rejection of the French proposal via media outlets to maintain the European meditation efforts. When the French president attempted at the end of August[28] to bring together the Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif and the representatives of the G7 summit including US President Donald Trump, Zarif boarded his jet immediately to achieve this end. But the attempt did not result in a meeting between the Americans and the Iranians as the Americans turned down this initiative.

The French president did not stop at the previous attempt, but he repeated it. This time, he wanted to bring together the US and Iranian presidents in an unofficial meeting away from the media limelight during the UN General Assembly meeting in New York.[29] But this attempt also failed for reasons brought forward by both the Americans and the Iranians.

4- Using the Files of Human Rights and Terrorism

The human rights and terrorism files are among the most important tools used by Europe to pressure Iran. Iran’s human rights record and terrorism are the main moot points between the two sides. The European Parliament leveled criticisms at Iran over violating human rights. European Parliament members, on March 14, 2019, called on Iran to immediately release human rights activists and journalists who have been jailed for exercising freedom of expression and their right to peaceful assembly.

Also, several European countries, including France and Norway, criticized the verdict issued against the Iranian lawyer and human rights activist Nasrin Sotoudeh.[30]

In the same context, on April 13, 2019, the European Union extended its sanctions in relation to human rights violations in Iran for one year.[31] These sanctions ban travel and freeze the assets and properties of 82 Iranian personalities and entities. The sanctions also include preventing EU countries from exporting equipment which could be used in domestic crackdowns and surveillance. These sanctions were imposed in 2011 and have been extended on an annual basis. They impact senior military officials, judges, police and intelligence officials, as well as commanders in the armed forces and directors of prisons.

As for the pressures in relation to the terrorism file, on January 9, 2019, the European Union approved sanctions on Iran over the involvement of Iranian diplomats in plotting terrorist operations in the Netherlands, France and Denmark. The sanctions included money and other financial assets owned by the Iranian Ministry of Intelligence as well as individuals affiliated with it being frozen.[32]

In the same context, the German government terminated the operating license granted to Mahan Air in Berlin on January 22, 2019, citing reasons related to safety. In addition, the Germans suspected that the airline was being used for military purposes.[33] Also, on March 20, France cancelled flights operated by Mahan Air as of April 1, 2019.[34]

III. The Factors Causing a Shift in the European Position on Iran

Despite the enthusiasm displayed by the European parties to maintain the nuclear deal after the US pullout from it in 2018, the European position in the latest phase has been impacted by several factors, including:

1- Refusing to Join the FATF

The Europeans said that the implementation of INSTEX depended on Iran approving the FATF bills, which would lead to Tehran amending laws related to money laundering and financing terrorism, while obliging Iran to make progress on other files. These files include Iran’s ballistic missile program, human rights violations, terrorism, and regional interventions. As a result of complications in activating INSTEX, the Expediency Discernment Council blocked the approval of the FATF bills and did not take any step forward in this direction until the grace period granted to Iran by the FATF expired in February 2020.

2- Ballistic Missile Tests

Iranian ballistic missile tests have raised concerns in Europe. These missiles pose a threat to the European territories. At the beginning of February 2019, the Iranian government released a short video featuring the test-firing of Hoveizeh.[35] The government claimed that the testing of the missile’s capabilities had been carried out for security and defense reasons. In another escalation, Iran tested the Shahab-3 missile on July 24, 2019.[36]

3- Threatening Navigation in the Gulf

Iran moved from the phase of political and diplomatic pressure to the phase of confrontation and hostility via attacking oil tankers, seizing them and posing a threat to navigation in the Arabian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz, through which one-fifth of the global oil supply passes per day. A series of incidents known as “the second Tanker War” led to the IRGC’s abduction of the British-flagged oil tanker Stena Impero.[37]

4- Iran’s Reduction of Its Nuclear Commitments

Since the beginning of the year, and given the policy of push and pull from the European side, Iranian officials made remarks in which they threatened to breach the nuclear deal and resume the enrichment of uranium as a means to exert pressure on the Europeans to prompt them to accelerate their diplomatic efforts and implement their promises.

Amid the United States and the Europeans tightening the noose around Iran and its economy, Tehran has undertaken several measures at an accelerating pace. The aim was to pressure the European countries. Iran announced a plan to reduce its nuclear commitments stipulated in the nuclear deal in phases.

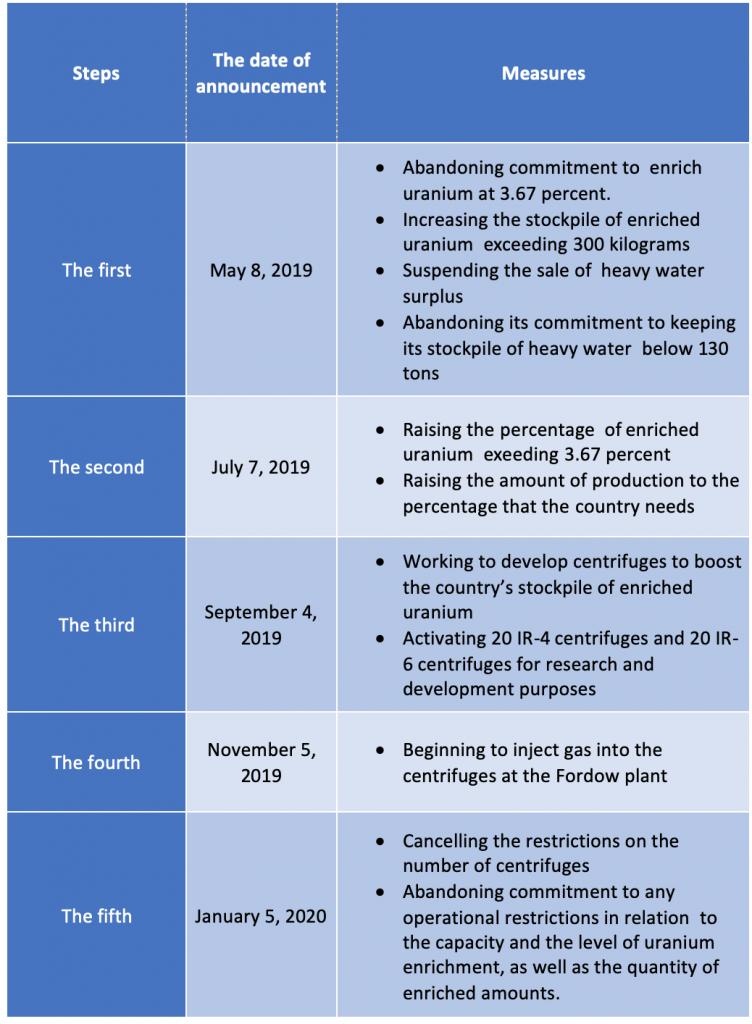

Table (1): Timeline of Iran Reducing Its Commitments Under the JCPOA

Source: Arms Control Association[38]

IV. The Diminishing Importance of the Nuclear Deal

Iran continued to reduce its nuclear commitments by taking the fifth step on November 5, 2020, announcing that it would fully abandon all restrictions imposed on the amount and percentage of enriched uranium as well as on the number of centrifuges.[39] The European Troika countries responded on January 14 in a joint statement, announcing the invocation of the dispute settlement mechanism as a deterrent measure against Iranian breaches.[40]

High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell indicated during a visit to Tehran following the European decision to activate the dispute settlement mechanism that the European parties do not seek to refer the nuclear file to the UN Security Council or cancel the nuclear deal. On the contrary, they seek to maintain the nuclear deal. He also reiterated the will of the European countries to avoid initiating the dispute settlement mechanism’s 15-day consultation period or moving ahead with the legal procedures arising from it in accordance with the deal, so that the concerned parties are able to negotiate and resume their commitments to the deal.[41]

It is worth mentioning that the meeting of the JCPOA joint commission was held afterwards on February 26, 2020. It resulted in easing the rising tensions among the European countries and Iran at the time.

The benefits arising from the deal were called into question by the European side after the US pullout and the increasing Iranian violations of its commitments over the past two years. The European gains have dwindled due to US sanctions and mounting security concerns following the Iranian testing of ballistic missiles. Moreover, Iran, on April 22, 2020, launched a military satellite named Noor-1 into space[42] which raised more concerns about its ballistic missile program.

Here, it should be noted that electing a Democratic administration in place of US President Donald Trump does not mean that it will be easy for the United States to return to the nuclear deal. The new US administration would face political and economic hindrances, such as the expiration of several clauses of the deal. Within months or within the next few years, a new US administration would witness curbs on Iran’s nuclear program being lifted. Second, it is difficult to revoke sanctions as US President Donald Trump has gone too far, with sanctions targeting Iranian citizens, entities, and institutions in Iran, which makes the cancellation of sanctions extremely difficult politically and logistically. Third, the Iranian presidential elections are approaching, which will be held six months after the US elections, with it highly likely that a candidate from the “conservative” trend will win the elections. This trend rejects the outcome of the current nuclear deal and opposes the principal of holding negotiations with the West.[43]

The European position on Iran since the end of 2019 has edged closer to the US position. The manifestations of this similarity were evidenced in the significant pressure exerted by the European countries on Iran in the files related to terrorism, and human rights, as well as their criticism of the ballistic missile tests and the recent condemnation of launching a military satellite into space. This shift in the European position coincided with the continued US pressure on them in the file related to extending the arms embargo on Iran in particular.

The expiration of the embargo on selling arms to Iran according to the nuclear deal is among the clauses which encouraged Tehran to remain committed to the deal. According to the Center of the European Council on Foreign Relations, the European side is aware of the consequences of any decision to extend the arms embargo, which will definitely impact the future of the deal.[44]

On one side, the European support for US efforts could prompt Iran to pull out of the nuclear deal and pull out of the nuclear nonproliferation treaty, according to the remarks of Iranian officials.

On the other side, opposing US efforts will push Washington to undertake initiatives to reinstate UN sanctions on Iran in accordance with the terms of the nuclear deal.

In both cases, the European side is aware of the growing Iranian danger to regional security, extending to the European continent. It also notices the absence of economic, political, or even nuclear gains from the agreement. In the meantime, Iran continues to reduce its commitments under the nuclear deal. Whether Europe supports or opposes US efforts, the outcomes and gains from the nuclear deal are no longer at the level desired when the deal was signed in 2015.

IV. The European Position and the Future of the Nuclear Deal

Considering the aforementioned, we can summarize the likeliest scenarios in regard to the European position towards the nuclear deal as follows:

1- Keeping the Deal Alive and Enforcing the INSTEX Mechanism

This scenario envisages that negotiations will be the diplomatic solution taken by Europe, which shall lead to the preservation of the nuclear deal. This could lead to improving relations between Iran and Europe to overcome the current stalemate and distrust which were the hallmark of relations throughout 2019. The aim is to implement the INSTEX mechanism in a manner that protects European firms from US sanctions. This scenario is backed up by the following:

- Iran has expressed readiness to return to its nuclear commitments if the European countries activate INSTEX in accordance with Iran’s aspirations. The aim is to facilitate commercial exchange to help salvage the Iranian economy which is suffering from a downturn.

- The strategic importance of the nuclear deal and its role in upholding the security of the region, which is considered one of the areas threatening European security.

- Completing the first commercial exchange deal via INSTEX on March 31, 2020. Medical equipment manufactured by a German firm was exported to the Iranian government at the value of 500,000 euros.[45] This first transaction has prepared the two sides to facilitate future transactions with small and medium-sized European firms.

- The possibility of a consensus emerging among European countries to unite to bring INSTEX into effect.

2- Maintaining the Nuclear Deal Without any European Guarantees

This scenario indicates that the two sides, Europe, and Iran, are clinging to the current political gains resulting from keeping the nuclear deal in place for the time being. This comes amid the continuation of a carrot and stick policy adopted by the European Troika which is countered with deliberate blackmails by the Iranian side such as threatening maritime navigation and conducting ballistic missile tests. This scenario is backed up by the following:

- The continuation of the nuclear deal is considered a political and diplomatic gain for Iran as it prevents coordination between the United States and Europe, which would increase pressure on Tehran.

- The Iranian government’s refusal to approve the FATF bills, which impedes the European desired objective of financial transparency in order to activate INSTEX.

- The Iranian government’s appreciation of European humanitarian aid worth 20 million euros,[46] which was intended to enable Tehran to fight the coronavirus outbreak.

- The Iranian government depending on the outcome of the US elections in 2020 and the policies of the new administration in case President Donald Trump is not re-elected.

- The continuation of the European-European divergence on the activation of European guarantees, including INSTEX, as well as disagreements on the policies adopted in relation to the moot points with Iran.

- Keeping open the channels of dialogue for the two parties, which enhances the possibility of reaching the desired future outcomes, taking into account the element of time and the possible change in the US position.

3- The Europeans’ Curbing of the Nuclear Deal

This scenario argues that there is a crack in the European-Iranian relationship which is deepening because of the steps taken by Iran to reduce its commitments and the European Troika’s invocation of the dispute settlement mechanism. This is in addition to the US pressure on its European allies to extend the arms embargo on Iran. As a result of mounting Iranian threats to maritime navigation in the Gulf, and an intensification of missile tests which strengthen its ballistic missile program, the European countries may take a decision to withdraw from the nuclear deal. This scenario is backed up by the following:

- Iran’s escalation and violation of its commitments under the nuclear deal. It committed its fifth breach of the 2015 nuclear deal, discarding operational limitations set by the deal on its nuclear program. In addition, it breached the restrictions on the number of advanced centrifuges it can possses and the amount of uranuim it can enrich.

- The Irainan hardliners exploited the US killing of the Quds Force Commander Qassem Soleimani to make the Iranian government follow their agenda; consequently, this would exacerbate the disagreements between the Europeans and Iranians.

- The Iranian government is currently facing an unprecedent crisis at home which may lead it to adopt an offensive stance against regional countries and US allies.

- The European activation of the DRM under the 2015 nuclear deal after the US withdrawal and submitting the nuclear file to the joint committee. This would lead to the whole nuclear deal collapsing and the reimposition of the UN sanctions which had been imposed on Iran before the 2015 nuclear deal.

- European-US rapprochement; the Europeans may support US efforts aiming to extend the UN arms embargo on Iran.

4- Reaching a New Nuclear Deal via European Mediation

According to this scenario, the Iranians and the Europeans do not have any further gains that can be achieved from the current nuclear deal; therefore, they are likely to agree to forge a new nuclear deal. The Iranians are likely accept a European settlement boosted by European-American coordination. This is a likely scenario because of the following:

- The deterioration of the Iranian economy to an unprecedented low level and the decline of oil exports which make up a huge portion of the government’s annual revenues to less than 300,000 barrels per day. This is in addition to the refusal of foreign firms and countries to conduct financial dealings or invest in Iran, which reduces the value of the Iranian currency and prevents the government from taking advantage of its natural resources.

- The worsening domestic problems and mounting popular discontent against the ineffectivness of the government in tackling sanctions and its monetary policies which have aggravated the situation further. The prices of foodstuffs and gasoline has increased as well as rampant corruption leading to popular uprisings against the government as was the case with the protests which broke out at the end of 2017 and November 2019.

- The costly alternatives on the table for the Iranian government. Nuclear escalation will not keep the country safe from US or Israeli strikes nor will the involvement in direct military confrontations prevent the government from collapsing at home because the Iranian military is in a woeful state. The government cannot necessarily keep things under control and remain in power.

- The European-American rapprochement in particular and the European perception that Iran has not honored its commitments under the nuclear deal is a pretext for it to break from the deal and to re-examine the negotiations on contencious issues regarding their disagreements with Iran.

Conclusion

The nuclear deal represents a vital interest for Europe, but it does not amount to a crucial and indispensable interest. The European countries insist on keeping it alive despite the US pullout from it since it has fulfilled its main objectives, particularly the supervision of Iran’s nuclear program under the auspices of the International Atomic Energy Agency and the P5+1. But as many of the nuclear deal’s benefits have disappeared, and particularly in light of Iran’s violations of its nuclear commitments, a decline in economic opportunities due to US sanctions, Iran’s threats to regional security/stability, and Iran’s intensification of ballistic missile testing, the European parties will not engage in hostilities with the United States for the sake of Iran.

Furthermore, the European position could turn out to be more consistent with the United States as time passes by, which was expected by Iran. Therefore, the Europeans may intend to keep the deal without promising any guarantees in the short run until the US elections are held, in case they can adopt a position which is different from their current stance. In the long run, it is likely that there will be a new nuclear deal with European mediation in case Iran stops showing hostility to the international community and abandons its expansionist ambitions. There is also a scenario based on European withdrawal from the deal in response to US pressures intended to extend the arms embargo on Iran or the ramifications of the European response to the extension decision which could cast a shadow of doubt over the future of the nuclear deal.

[1] “Understanding the Nuclear Agreement With Iran in Ten Minutes,” France Diplomacy – Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, https://bit.ly/3etxmTo, accessed March 15, 2020.

[2] “What Is the Iran Nuclear Deal?” DW, October 6, 2017, accessed March 3, 2020, https://bit.ly/2VimTCy

[3] Ali Fathollah-Nejad, “Europe and the Future of Iran Policy: Dealing with a Dual Crisis,” October 2018, Brookings Doha Center, https://brook.gs/38Y2fNm.

[4] Gary Samore, “The Iran Nuclear Deal: A Definitive Guide,” Harvard Kennedy School, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, August 2015, https://bit.ly/3h5VGvb.

[5] Gérard Araud, Kelsey Davenport and Elizabeth Philipp,“A French View on the Iran Deal: An Interview with Ambassador Gérard Araud,” Arms Control Today 46, no. 6 (July:August), 2016, 15-20.

[6] Suhaila Mahmoud Abdel-Anis, “Iranian-European Relations: Dimensions and Controversial Files” (Abu Dhabi: Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research, 2007) 126, 32-33.

[7] “Iran’s Economy in 2015,” United States Institute of Peace, December 17, 2015, accessed April 2, 2020, https://bit.ly/2xGvupG.

[8] Fathollah-Nejad, “Europe and the Future of Iran Policy.”

[9]Aisha Al Saad, “Parameters of Iranian Foreign Policy,” Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, November 2018, 23.

[10] “Iran: Two Years After the Lifting of International Sanctions,” Global Economic Dynamics, January 16, 2016, accessed April 20, 2020, https://bit.ly/3etyxCe.

[11] “5 Ways the Nuclear Deal Will Revive Iran’s Economy,” Time, July 16, 2015, accessed April 10, 2020, https://bit.ly/2VILRdy

[12] Al Saad, “Parameters of Iranian Foreign Policy,” 29-30.

[13] Ray Takeyh, “Why Iran Won’t Make Another Nuclear Deal,” National Review, March 19, 2020, accessed 08 Apr 2020, https://bit.ly/2VgJgZg

[14] Ibid.

[15] “Iran Sees Lifting of UN Arms Embargo in 2020 as ‘Huge Political Goal,” Reuters, November 11, 2019, accessed April 1, 2020, https://reut.rs/2wOPpCu

[16] “UN Security Council Resolutions on Iran,” Arms Control Association, August 2017, accessed April 10, 2020, https://bit.ly/2xGGbZu

[17] Fathollah-Nejad, “Europe and the Future of Iran Policy.” And see: Simon Gass, “Finding the Sweet Spot: Can Iran Nuclear Deal Be Saved?” European Leadership Network, March 1, 2018, accessed March, 2020, https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep17422.

[18] Emily B. Landau and Ephraim Asculai, “The JCPOA, Three Years On,” Institute for National Security Studies, 2019, accessed March 18, 2020, https://bit.ly/2AZgtB1.

[19] Aisha Al-Saad, The Determinants and Evolution of Iran’s Foreign Police Toward the Gulf State in the Context of Iran Nuclear Negotiation (Beirut: Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, 2018), 55.

[20] Peiman Seadat, “In 2019, the Nuclear Deal is Hanging by a Thread,” Euro News, January 4, 2019, accessed January 2, 2020, https://cutt.us/qxrig

[21] “The European Union Expresses Its ‘Deep Concern’ Over the Iranian Ballistic Missile Activities,” Radio Farda, accessed January 7, 2020, https://bit.ly/2Sf5oU8.

[22] “Complete Implementation of FATF Is a Must for Implementing INSTEX,” Mashreq News, accessed February 6, 2020, https://bit.ly/2UxCU4q

[23] “European Union Establishes Legal Entity to Continue Trade With Iran and Avoid US Sanctions,” BBC, September 25, 2018, accessed January 10, 2020, https://cutt.us/CKahc.

[24] “European Row Threatens Agreement on the Financial Mechanism With Iran,” Erm News, accessed January 10, 2020, http://cutt.us/xPDsV

[25] “INSTEX: Europe Sets up Transactions Channel With Iran,” DW, January 31, 2019, accessed January 2, 2020, https://cutt.us/RfrNm.

[26] “Six European Countries Join EU-Iran Financial Trading Mechanism INSTEX,” EurActive, November 29, 2019, accessed January 2, 2020, https://cutt.us/5yN6y

[27] “Adviser to the French President From Tehran: I Am not a Mediator and do not Carry an American Message,” Dot Gulf, accessed August 7, 2018, https://cutt.us/cZezu

[28] “Macron Tries to Arrange a Trump Meeting With Iranian Leader,” AP News, August 26, 2019, accessed January 10, 2020, https://cutt.us/Sd9pG

[29] “Macron Tried to Broker Meeting Between Trump, Iran’s President,” The Wall Street Journal, September 24, 2019, accessed January 15, 2020, https://cutt.us/WhREV

[30] “French Official Says Iran Does not Have a Carte Blanche for Human Rights,” Radio Farda, accessed April 3,2020, https://bit.ly/2FjbJ7p

[31] European Council, Iran: Council extends by one year sanctions responding to serious human rights violation, 8 April 2019, accessed 22 Jan 2020. https://cutt.us/0qQ4W

[32] “European Sanctions on Iran After Accusing it of Planning to Assassinate Dissidents in the European Union,” France 24, accessed February 17, 2019, http://cutt.us/PStzD

[33] “Bowing to US Pressure, Germany Bans Iran Airline From Its Airspace,” Premium Times, January 21, 2019, accessed February 6, 2019, http://cutt.us/Zjcro

[34] “After Germany, France Cancels Flights of Airline Affiliated With Revolutionary Guard,” Al-Arabiya, March 20, 2019, accessed January 20, 2020, https://cutt.us/RjKLm.

[35] “Iran Tests New Cruise Missile,” DW, February 1, 2019, accessed January 15 2020, https://cutt.us/HypCq.

[36] “In Escalation, Iran Tests Medium-Range Missile, US Official Says,” The New York Times, July 25, 2019, accessed January 17, 2020, https://cutt.us/8UaRz.

[37] “Annual Strategic Report for 2019,” The International Institute for Iranian Studies (Rasanah), accessed April 20, 2020, https://bit.ly/30aPif7.

[38] “Timeline of Nuclear Diplomacy with Iran,” Arms Control Association, January 2020, accessed January 23, 2020, https://cutt.us/dekah.

[39] “Iran Abandons Nuclear Deal Limitations in Wake of Soleimani Killing,” NPR, January 5, 2020, accessed March 3, 2020, https://n.pr/2TmymAe

[40] “Iran Nuclear Deal: European Powers Trigger Dispute Mechanism,” BBC, January 14, 2020, accessed March 2, 2020, https://bbc.in/39qC6q2

[41] “Iran: Remarks by High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell at the Press Conference During his Visit to Tehran,” European Union External Action, February 4, 2020, accessed March 3, 2020, http://bit.ly/39BfTp5

[42] “Iran Says It Launched a Military Satellite into Orbit,” The New York Times, April 22, 2020, accessed April 27, 2020, https://nyti.ms/357rH18

[43] “Washington’s Return to Iran’s Nuclear Agreement Almost Impossible Under any President,” Independent Arabia, July 23, 2019, accessed April 2, 2020, https://bit.ly/3cDrSUb.

[44] How Europe Can Avert a Clash Over the Iran Arms Embargo,” European Council on Foreign Relations, April 29, 2020, accessed May 19, 2020, https://bit.ly/3e4RpXs

[45] “Iran Daily: UK, France, and Germany Send Medical Supplies to Tehran, Bypassing US Sanctions for 1st Time,” EA World View, April 1, 2010, accessed April 1, 2020, https://bit.ly/2X2zzyY.

[46] “EU to Give €20 million to Aid Sanctions-hit Iran in Coronavirus Fight,” France24, March 23, 2020, accessed March 31, 2020, https://bit.ly/3aH3wZi