Introduction

The return of Turkish influence to Libya is an integral objective for the Erdogan government, given its promising investment opportunities, oil resources, and significant geopolitical location: serving as a springboard for Turkish influence into the Mediterranean and a land bridge connecting the Arab world, Africa, and Europe. Now, Turkey is exploiting the current conflict and divisions inside Libya to implement an old scheme, which was revived following the so-called Arab Spring, to expand Turkish influence in the Arab world through the Maghreb. For this scheme to be successful, Turkey must impose a type of soft “guardianship” over some Arab Islamic countries to exploit their current state of fragmentation.

Turkey’s entrance into Libya was recognized by the Libyan Government of National Accord and supported by radical Islamic currents. On January 20, 2020, the Turkish Parliament approved a motion submitted by President Erdogan to authorize the deployment of Turkish troops to Libya. Two memorandums of understanding (MoUs) were signed between Erdogan and Fayez al-Sarraj, the head of the Tripoli-based government – one MoU was on security and military cooperation and the second one was on the delimitation of maritime jurisdictions. As a result, Erdogan was granted the authorization needed to deploy Turkish troops in Libya. According to the motion, “The risks and threats are coming from Libya to Turkey and the whole region.” This was Ankara’s pretext.

This study aims to review Turkey’s political and economic influence in the Maghreb in general, Ankara’s motivations for supporting the Libyan Government of National Accord, the nature of Turkish support to Libya, and the consequences and risks of Turkish influence in Libya as well as its impact on the Arab region and the international community. The study aims to project the future scenarios of Turkey’s political and military presence in Libya.

There are two parallel governments operating in Libya: the Sarraj government, partially backed by the international community and General Khalifa Haftar’s rival government, supported by Libya’s elected Parliament. They have invoked dramatic and rapid changes in Libya. This internal division paved the way for several regional and international actors to intervene in Libya, creating a more fertile climate to expand Libya’s civil war over a longer period and across wider regions. This has made Libya one of the most complex conflict situations, where religion is intertwined with politics; geography with economics; and regional with international issues.

I- Turkey’s Objectives in the Maghreb

Turkey has a very long historical experience in ruling over colonies, which motivates it to expand its influence in the Maghreb. Nowadays, during Erdogan’s era, Turkish colonialism is carried out via cultural, economic and military means in a race to control the southern coasts of the Mediterranean. Erdogan directed Turkish military commanders to improve the country’s naval forces in order to entrench a Turkish presence in the Mediterranean. Furthermore, Erdogan has adopted a hegemonic naval strategy developed by nationalist Turkish military commanders called the “Blue Homeland Doctrine” [Mavi Vatan] to control the Aegean Sea and most of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.[1]

- Political and Ideological Interests

The Justice and Development Party (AKP) has developed the so-called “return of Ottomanism,” or “neo-Ottomanism” as a national policy. It has attempted to combine the republican values of Atatürkism with Ottoman glory, hence serving the party’s interests at home and abroad. The party has employed all propaganda tools available to introduce and convince the Turkish people of this new national policy linking their present to their old Ottoman heritage.

After gaining public acceptance of this new policy at the domestic level, following years of economic growth since the AKP took power, the Turkish leadership has worked to expand its vital spheres of influence across the Middle East and North Africa, exploiting the power vacuum resulting from the Arab Spring. After the collapse of President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali’s regime in Tunisia in 2011, and the victory of Ennahda in the elections, which is an Islamist movement similar to the AKP, Turkish-Tunisian relations were boosted unprecedentedly. President Erdogan became a role model for Islamists in Tunisia.

Both the Turkish and Tunisian governments adopt convergent positions regarding the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord. President Erdogan in late 2019 visited Tunisia with the Turkish ministers of defense, foreign affairs and intelligence when they were preparing to deploy Turkish troops and military equipment to Libya in support of the Tripoli-based government. The visit of Rached Ghannouchi, head of the Ennahda Party and the Tunisian Parliament speaker, to Turkey on January 12, 2020, invoked harsh public criticism amid rising calls to propose a motion of no-confidence against Ghannouchi, accusing him of turning Tunisia into a Turkish logistical base. This harsh criticism emerged following reports stating that a Turkish plane loaded with aid to Libya had landed in southern Tunisia.[2]

Turkey-Algeria relations have prospered since the AKP came to power in Turkey in 2002. Since then, Erdogan has visited Algeria three times: the first visit in 2006 when he was prime minister; the second visit in February 2018; and the third visit in January 2020. Amid its efforts to find a peaceful way out of the Libyan crisis rising at its border, Algeria opened discussions with Turkey after it intervened in Libya. Though it adopts a similar position to that of Turkey regarding the Sarraj government – as an internationally-recognized government – it still has some reservations about Turkey’s military role in Libya, especially Erdogan’s deployment of Syrian mercenaries to Libya, triggering fears among Algerians of their impact on Algeria’s national security.

2-Economic Interests

Turkey has exerted considerable efforts to penetrate the Maghreb economies. According to statistics released in 2018, the estimated population of the Maghreb is approximately 110 million people (43.3 million in Algeria, 42.1 million in Morocco, and 12 million in Tunisia, 7 million in Libya and 3 million in Mauritania). After the Arab Spring, Turkish exports to the Maghreb countries bounced to $6.570 billion in 2018, compared to $4.857 billion in 2010 due to Turkey’s rapprochement with the new political systems, in which Islamic parties play a greater role. On the contrary, the Maghreb countries have not increased their exports to Turkey; their exports declined to $2.4 billion, registering a huge trade deficit.[3] In particular, Morocco’s trade deficit with Turkey increased dramatically moving from 4.4 billion Moroccan dirhams (approximately $496 million) in 2006 to 16 billion dirhams ($1.66 billion) in 2018.[4] Tunisia shuts down 374 textile manufacturers every year due to the competition they face from global textile firms, especially from Turkish and Chinese ones. Tunisia’s trade deficit with Turkey grew to more than $750 million.[5] Turkish investments in Algeria, Turkey’s largest trade partner in Africa, increased to more than $3 billion. The two countries seek to boost it to $5 billion.[6] Algeria ranked fourth among Turkey’s gas suppliers; in 2014 it was agreed to supply gas to Ankara for 10 years. Its natural gas exports to Turkey increased to 4.4 bcm in 2018.[7]

3-Getting Closer to Africa

Turkey’s growing foray into Africa started when President Erdogan came to power in 2003. Ankara spearheaded the strengthening of relations with the African countries, declaring 2005 as the “African Year.” Ahmet Davutoğlu, the former Turkish foreign minister, crafted Turkey’s strategic policy towards Africa. He presented, back then, the general framework of Turkey’s foreign policy pursued by the AKP; restoring Turkey’s historical presence in the Ottoman Empire’s former territories. The party opted to revive the Ottoman Empire’s historical heritage to reap vital economic and political gains. Africa is blessed with fertile soil, mineral treasures, and oil resources. It is seen as a high yielding market for Turkish products and investments. “The rise of Africa will support the rise of Turkey and vice versa. We will strengthen our historical special ties in every field and the 21st century will be the century of Africa and Turkey,” said Foreign Minister Davutoğlu.[8]

Since 2005, President Erdogan has made 40 visits to 26 countries in Africa and has inaugurated several embassies. Africa has become a strategic region for Turkey. During the Bashir reign, Ankara leased Sudan’s Suakin Port in the Red Sea – opposite Jeddah Port — with $4 billion, which Qatar paid.[9] Suakin island was of great strategic significance to the Ottomans, it was – for a short period of time –the capital of the Ottoman Empire’s Habesh Eyalet, from which it managed control over maritime navigation. The Sudanese revolution in December 2018 was a dramatic turning point for Turkey-Sudan relations; calls were made to rethink the agreement regarding Suakin Port. The Sudanese transitional government believes that the Turkish presence in the country supports the former Sudanese government because of shared Muslim Brotherhood links.

Turkey has employed soft power tools in Africa to present itself as a just country compared to the Western countries which have a foothold in Africa. Ankara has succeeded in establishing a partnership with Africa, its population exceeds 1.2 billion people and domestic production is valued at nearly $2.5 trillion. Turkey’s trade volume with the African countries was more than $20 billion in 2019 compared to $3 billion in 2003 and $100 million in 2000. Turkey signed agreements for trade and economic cooperation with 46 countries in Africa. Further, it concluded bilateral investment treaties – to protect and stimulate trade – with 28 countries and treaties to avoid double taxation with 12 countries.[10]

4- Bargaining Chip Against Europe

Turkey had been negotiating to be a member state of the European Union (EU) since 2005; the accession negotiations were halted in 2016. Subsequently, Turkey resorted to blackmailing the EU with Syrian migrants – Ankara opened its border, allowing them to flood into Turkey and then into Europe. Approximately 900,000 migrants entered Europe from Turkey in the early months of 2016 ( January and February). The EU, as a result, signed an agreement with Turkey to stop the flow of migrants to the EU, offering Turkey 5.6 billion euros (approximately $6 billion to $7 billion) in this regard.[11] Apparently, Erdogan is planning to conclude a similar deal with Europe via his intervention in Libya, using the card of illegal migrants once again in Africa, if the Government of National Accord falls.[12]

Map1: Countries of the Mediterranean Sea

II- Motives Behind Turkey’s Presence in Libya

During the era of Ottoman invasion, the Turks occupied Libya for nearly 360 years. It was a period marked by oppression leading to the eruption of several revolutions. Eventually, the Ottomans relinquished Libya to the Italians in 1912 in return for restoring the Aegean Islands (the Dodecanese) to the Ottoman Empire in the Treaty of Ouchy (also known as the Treaty of Lausanne). Based on this historical record, Erdogan has said that there are 1 million Turks living in Libya, adding that he should fight like Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who was a soldier in the Ottoman army in Libya.[13]

The Libyan crisis has dramatically shifted in favor of the Libyan National Army, prompting the Sarraj government to request Turkey’s military assistance to strengthen its forces to confront the progression of the Libyan National Army. Within a few months of Turkey’s military assistance, the balance of power tilted in favor of the Sarraj government; consequently, Sarraj is now in a much better and more powerful position to negotiate a settlement regarding Libya’s future. The most prominent motives driving Turkey’s intervention in Libya are as follows:

1- Economic Motives

A- The Power Sector

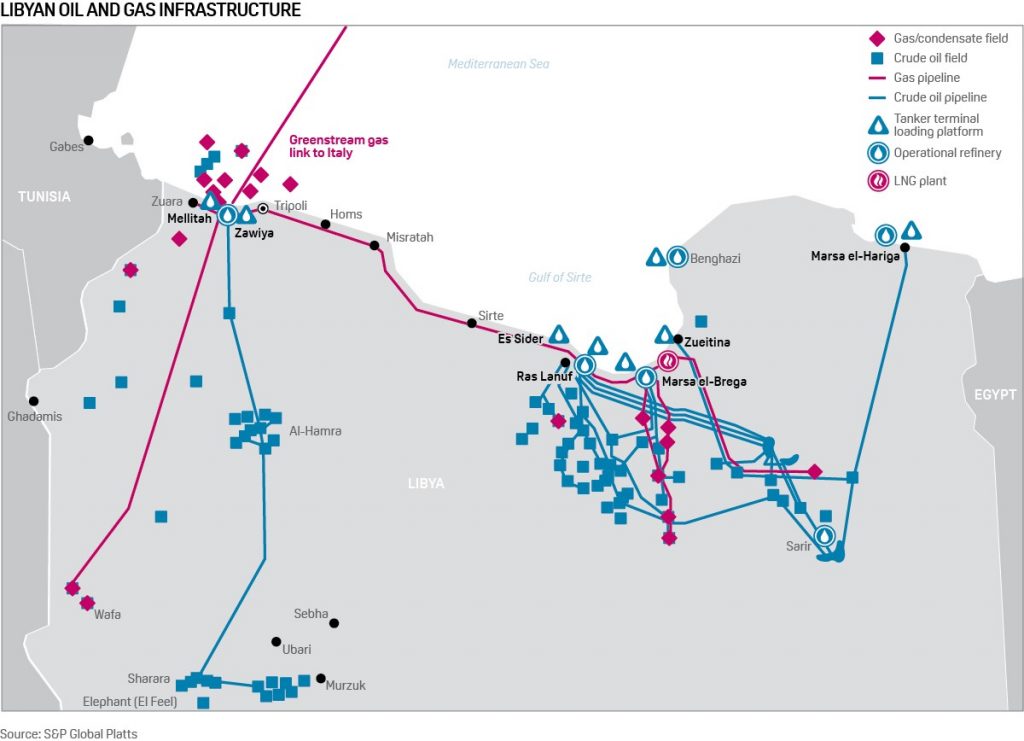

Oil was first discovered in Libya in 1958 and officially produced in 1961. It constitutes 94 percent of the country’s revenues, covering the costs of various Libyan sectors. Since the Libyan uprising, oil production and exports were hugely impacted leading to most oil companies that were involved in oil exploration, production and maintenance withdrawing from Libya. Oil production was halted in January 2020 by tribal leaders as they closed most of the ports and oilfields in eastern Libya, accordingly, living conditions worsened.

Turkey has taken various steps to reap considerable gains from the Libyan war to secure a permanent power supplier. For 20 years, Turkey has been importing nearly 95 percent of its oil needs from Libya. It aims to be Libya’s oil distributor to Europe, replacing Libya’s National Oil Corporation. According to OPEC’s Annual Statistical Bulletin 2017, Libya has the fifth largest-proven oil reserves in the Arab world with 48.5 billion barrels; 3.76 percent of the world’s oil reserves. Saudi Arabia is home to the world’s largest-proven oil reserves, estimated to be 263.9 billion barrels; 20.7 percent of the world’s reserves. Further, the bulletin confirms that Libya is ranked eighth in the list proven natural gas reserves in the Middle East with 1.5 trillion cubic meters.[14]

Libya is the largest shale oil producer in the Arab world and ranks fifth in the world. Its reserves increased from 48 billion barrels to 74 billion barrels. These huge shale oil reserves are in Libya’s northwestern and southern regions. They have increased the default age of oil production in Libya from 70 years to 112 years. Further, Libyan natural gas reserves have increased their threshold; from 55 trillion cubic meters to 177 trillion cubic meters. Libya’s total reserves of shale oil are estimated to be 613 billion barrels.[15]

Map 2: Libyan Oil and Gas Infrastructure

The state-run Turkish Petroleum Corporation (TPAO), with investments in Libya exceeding $180 million, had officially started oil exploration in Libya in 2000 and stopped in 2014. It resumed its oil activities after concluding a new agreement with Libya which focuses on oil exploration operations in Turkey’s exclusive economic zones that were finalized in the agreement. TPAO will further, according to the agreement, develop joint energy projects in the so-called “Oil Crescent;” a region in northeastern Libya.[16] However, major global oil firms have a strong presence in Libya such as: the French oil company Total; the Italian oil company Eni; the US oil company ConocoPhillips Hess Corporation, and the German gas and oil producer Wintershall.

B-The Construction Sector

Turkish contracting companies have handled a considerable number of projects since 1974, but after the Arab Spring, Turkish exports to Libya sharply declined and its economic projects – worth $19 billion – stumbled, affecting the Turkish laborers in Libya. Furthermore, Libyan tourists to Turkey decreased.[17] As part of its efforts to restore its assistance and economic activities and ensure more investments – especially in the construction sector – Turkey sought to secure a larger number of potential investment opportunities in Libya’s construction sector and infrastructure worth $120 billion.[18]

2. Political and Ideological Motives

Turkey believes that its presence in Libya boosts its influence and projects its power. It seeks to entrench and deepen its influence there to achieve several factors, most prominently: create a new regional order to transform its role from solely being a regional player into a more powerful and outstanding major player that can strengthen the Muslim Brotherhood’s presence in the Maghreb and Egypt.

At home, Erdogan, via his intervention in Libya, aims to boost support for the AKP in the upcoming elections; he is exerting all efforts possible to secure the votes of nationalists and Islamists by appealing to their nationalistic and Islamic sentiments and by creating a crisis that provokes the international community. Erdogan also strives to export his ideology to the Arab countries, whom he still views as strategic and ideological rivals, accusing them of destroying the Ottoman Empire. The architects of Turkish polices aspire to establish a fake Turkish identity amongst Libyans living in the country’s western regions, based on historical inaccuracies about the Ottoman era. The Turkish National Intelligence Organization (MIT) and its branches have been endeavoring to achieve this goal by promoting Turkey’s narrative about Ottoman heritage and the Turkish language.[19]

III- The Nature of Turkey’s Military Assistance to the National Accord Government

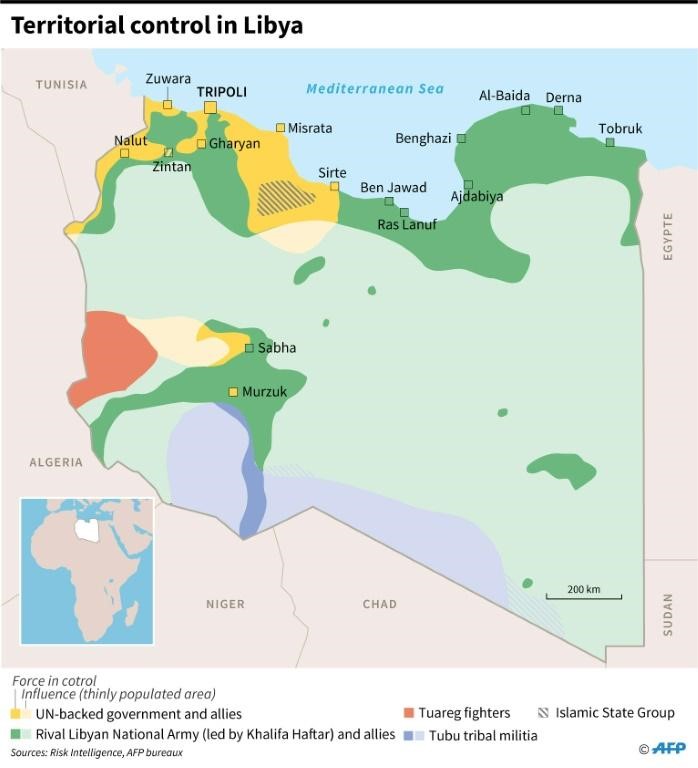

In 2014, General Khalifa Haftar emerged as a key player in Libya’s crisis. He expelled the radical Islamists from Benghazi, conquered with the Libyan National Army eastern Libya and started unifying the country by creeping westward to attack Tripoli to topple the Sarraj government. Haftar’s forces retreated from the outskirts of Tripoli back to Sirte, 450 kilometers east of Tripoli. He lost what he had achieved in the long months of fighting. The losses experienced by Haftar’s forces were a direct result of a change in the balance of power on the ground, following Turkey’s military assistance to the Sarraj government. Turkey’s intervention had started years ago when Haftar launched Operation Karama (Dignity); a war against terrorism in Benghazi.

Map 3: The Forces Involved in the Fighting in Libya Before Turkey’s Military Assistance (January 8, 2020)

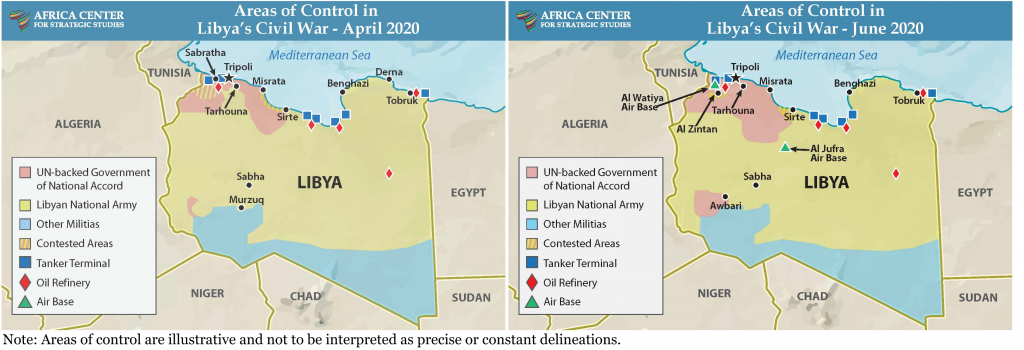

Libya from April-May 2020 witnessed dramatic and influential changes in favor of the National Accord Government at the expense of Haftar’s forces. The government managed to expand its control stretching over 7,000 square kilometers. The map below shows the areas controlled by the Government of National Accord in April and early June 2020.

Map 4: Shifts in Areas of Control in Libya

On June 25, the Turkish troops launched a wide scale ground offensive to control the Oil Crescent region in eastern Libya, involving F-16 fighter jets and Turkish frigates. The Turkish army crept eastwards up to the power plant in Sirte before retreating to Buwairat Al-Hassoun. By this military move, Erdogan aimed to capture the oil fields to enable the Government of National Accord to compensate Turkey’s new and old losses in Libya.[20]

- Sending Troops

Before concluding its agreement with the Government of National Accord, Turkey had sent an advisory committee with its troops to Libya. Turkey’s military presence expanded in the country after the Government of National Accord requested a wide-scale intervention, which turned the tide of Libya’s war in favor of the Sarraj government. The military MoU concluded between Turkey and Libya and the approved motion submitted by President Erdogan to authorize the deployment of Turkish troops to Libya enabled Turkey to provide all types of military and security support to the Government of National Accord, including the establishment of Turkish bases in Libya. It is worth mentioning that the MoU between President Erdogan and Sarraj provides a “quick reaction force” to Sarraj’s security and military forces. It also includes sending Turkish military advisors; forging joint military plans and exercises; and Turkey’s financial and military equipment assistance to Libya. The Erdogan-Sarraj MoU also allows bilateral cooperation on intelligence and operations; weapons systems; and using military equipment of ground, air, and naval forces. According to the MoU, a joint office for defense and security cooperation shall be established in Turkey and Libya. Further, Ankara and the Government of National Accord discussed allowing Turkey to use the Misrata naval base and Al-Watiya airbase in Libya. [21]

2-Arms Supplies and Operational Support

Turkey transfers arms to Libya by sea and air routes. It has allocated a huge budget to develop and manufacture fast and sophisticated vessels and submarines, advance air force capabilities and to expand its drone fleet. The Turkish cargo ship “Amazon,” arrived at Tripoli port in May 2019 loaded with 40 armored vehicles for the Government of National Accord-backed militias in Tripoli. The Libyan National Army announced in August 2019 that it shot down a Turkish military cargo plane loaded with ammunition, drones, and multi-service drones.[22]

Turkey’s military assistance has gone through three tracks: first, Turkey’s production and delivery of drones, armored personnel carriers, anti-tank warfare, light and medium arms to Libya. Second, the supply to Libya of old arms stored in Turkish depots, including aircraft, tanks and artillery. Third, Turkey’s purchase of arms from Eastern Europe and the United States for its army and then re-selling these to its militias in Libya at a profit.

Through its operational support, Turkey aims to control one side of Tripoli’s outskirts, thus demarcating these outskirts as Tripoli’s new border. The Turks would then enhance their military presence to defend the newly controlled outskirts and attack the territories nearby, hence effectively drawing dividing lines so that they can announce Tripoli as a state on its own. Later, the Turks will continue their battles to control the rest of the Libyan provinces. The Libyan army revealed that Turkey mobilized its troops in eastern Misrata and “deployed advanced military equipment, including surface-to-air missile platforms and long-range field artillery batteries, in addition to large quantities of various war munitions.”[23]

However, Turkey faces several strategic hurdles in its supply of arms to the Libyan Government of National Accord, including problems related to combat and logistical support, and weapon capabilities, and their endurance in operations. Another obstacle is that Turkey is 1,500 kilometers from Libya, raising many logistical problems for Ankara, which is not used to deploying its troops in faraway regions. Further, Turkey cannot impose complete control over Libya’s airspace because it cannot sufficiently carry out in-flight refueling for its air forces and cannot provide close air support (CAS) for its troops and National Accord ground forces.

3- Re-recruitment of Syria’s Missionaries in Libya

Erdogan and his government enjoy strong relations with Libya’s militias, most prominently, the militias affiliated to the Muslim Brotherhood and the Kataib Misrata (Misrata Brigades). This is in addition to his strong relations with the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) and other militias fighting against Libya’s national army.[24] Turkey’s objective behind establishing ties with such groups is to recruit them in its proxy wars, given the possibility that the Turkish people may object to risking regular Turkish troops.

Through its proxy militias, Turkey recruited thousands of Syrian fighters in Libya. According to statistics, the number of Syrian fighters Turkey deployed in Libya is more than 10,000 fighters. The first wave of these fighters arrived in Turkey in late 2019, later they were sent to Libya. The National Accord government promised them monthly salaries and accommodation. [25] International law prohibits the recruitment of missionaries and using them for terrorist acts, however, Turkey is still keen to use them for two main reasons: first, to prevent the influx of militias into Turkey in case the Syrian regime manages to completely control northern Syria; second, to support the Sarraj government and further expand Turkish influence in Libya.

IV-Repercussions of Turkey’s Intervention in Libya

After Turkey and Libya’s Government of National Accord signed an MoU on the delimitation of maritime jurisdiction areas in the Mediterranean and an MoU on security and defense on November 27, 2019, Libya entered a phase of increasing tensions prompting many national and international parties to curb Turkey’s acts in Libya. The two MoUs faced local and international rejection because they exceed the powers of Sarraj as identified in the UN brokered agreement in Skhirat. In addition, the maritime treaty violates international maritime law as there is no sea border between the two countries.

- Violating Libya’s Sovereignty

Turkey aspires to be the most influential power in crafting Libya’s political future. It applied for an exploration permit in the areas included in the signed maritime treaty. According to the Turkey-Libya maritime treaty, exploration and pipeline construction must be agreed by the two countries. The Libyan National Army, the Libyan Parliament, and the temporary government rejected the two MoUs because they are illegitimate/illegal.[26]

2-Turning Libya Into a Terrorist Hotbed

The looming danger of creating a terrorist hotbed poses a significant threat to the North African countries, especially to Egypt. In addition to deploying fighters, radical ideologies will be exported as well – Turkey is exploiting the insecurity and militarization across Libya. It will be more dangerous if Arab and African young men, who suffer from harsh living conditions and unemployment, are recruited to join these militias. Given the attractive financial package offered to fighters in Libya, it is expected that fighters from other nationalities will move to fight in Libya, which will eventually turn into a hotbed for terrorists and missionaries.

3-The Control of Militias Affiliated to the Muslim Brotherhood

Turkey seeks to maintain the Muslim Brotherhood’s project in North Africa after it declined in Tunisia, Algeria, and Egypt. If Turkey succeeded in achieving this goal, Libya will be the bedrock of the Muslim Brotherhood project in the region to revive its power after losing political significance. Libya is the best country for the Muslim Brotherhood for several reasons: Libya’s geographical location between Egypt and the Maghreb countries; wealth and abundant natural resources; and the tribal psychology of the Libyan people as they have resisted and struggled against occupiers in the past.

V-Regional and International Reactions

1-Arab Reactions

A- The Reaction of the Arab League

The temporary Libyan government in eastern Libya called on the Arab League, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, and the African Union to take urgent steps to withdraw their recognition of the Sarraj government and to condemn the Turkish mobilization in Tripoli. The Arab League expressed “serious concern over the military escalation further aggravating the situation in Libya and which threatens the security and stability of neighboring countries and the entire region.”[27]

B-Egypt’s Position

Egypt has serious concerns over the impact of Turkey’s presence in Libya on its national security, given the 1,000 kilometer shared border with Libya. Thus, Egypt condemned the Erdogan-Sarraj agreement from the very beginning and endeavored to mobilize international efforts to thwart Turkey’s military presence in Libya, stressing its support for the Libyan National Army led by Khalifa Haftar.

The pro-Turkey NGA militias crossing the Sirte and Al-Jufra line: a defense front, prompted the Egyptian army to cross Libya’s eastern border to protect and defend the Egyptian border. The Egyptian army is more likely to succeed militarily as its logistical supply base is quite near unlike the Turkish army, which does not have any logistical bases nearby.[28] The Egyptian army will advance to the extent enabling it to provide Haftar’s forces with logistical and combat support to boost their spirits and protect their rearguard. Then it will be easier for Egypt to creep further to control eastern Libya and probably Tripoli.

C-The Position of the Maghreb Countries

The Maghreb countries cannot overlook the rising tensions in Libya, which threaten their security and pave the way for the influx of migrants, who will constitute an unbearable economic burden on them. The Arab Maghreb Union (AMU) could not reach a common ground and adopt a clear position in regard to the Libyan crisis. The foreign policies of the Maghreb countries are impacted by many regional and international factors; therefore, they adopt different positions regarding Libya. Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, do not support Haftar, and are more politically inclined towards the Sarraj government, and welcome Turkey’s political role. Yet, officially, they express their opposition to Turkey’s military support to Libya due to concerns that Libya will turn into a “new Syria,” consequently, creating dangerous security problems for them.

Tunisia has lost its position in the Libyan market; it is no longer amongst Libya’s top 10 trade partners while Turkey has become the third largest exporter to Libya. There are only 20,000 Tunisians working in Libya. As the Tunisian presence is fading in Libya, Turkish products have increased even in territories outside the control of the Sarraj government. [29]

Amongst the Maghreb countries, Algeria is extremely concerned about the Libyan crisis and rejected Haftar’s military offensive. At the same time, Algeria declared its objection to any foreign powers in Libya.

Morocco has adopted the most reserved position regarding the Libyan crisis, though the UN-brokered agreement which led to the establishment of the Government of National Accord was held in the Moroccan city Skhirat. Though Moroccan official statements on Libya are quite few, they reflect the country’s support for the Government of National Accord. The Moroccans still believe that the Skhirat agreement is good and forging many other initiatives on the Libyan crisis will lead to disagreements.[30] However, Morocco will be more cautious regarding Libya’s crisis for the following reasons: first, any uncalculated engagement from Morocco in the crisis will invoke Algeria, which views Libya as its backyard. Algeria will consider any Moroccan military support to the Turkish troops as a direct threat against it. Second, Morocco is fully aware of the complexity of the Libyan crisis, which may last for years to come, so there is no room for taking risks.

2-The International Response

A- The United Nations

Turkey violated the UN arms embargo on Libya, according to the UN Panel of Experts report, which is released every three months as an update on the UN Arms Embargo Resolution. According to paragraph 13 (b) of Resolution 2009 (2011), “the supply, sale or transfer to Libya small arms, light weapons and related material, temporarily exported to Libya for the sole use of United Nations personnel, representatives of the media and humanitarian and development workers and associated personnel, are to be notified to the Committee, and should include the following information.”[31]

In a statement, UN Secretary-General António Guterres, called for an immediate ceasefire in Libya and warned Turkey against sending troops to Libya. He said, “Any foreign support to the warring parties will only deepen the ongoing conflict and further complicate efforts to reach a peaceful and comprehensive political solution.” In addition, a statement from Guterres’ spokesperson said, “The Secretary-General reiterates that the continued violations of the Security Council arms embargo imposed by resolution 1970 (2011) and as modified by subsequent resolutions, only make matters worse.”[32]

B- Europe and NATO

The Turkey-Libya agreement mapping out maritime boundaries deepened disagreement between Brussels and Ankara. In a statement, the EU leaders condemned the maritime treaty because it is a violation of “the international law of the sea, the principle of good neighborly relations and the sovereignty and sovereign rights over the maritime zones of all Member States [….] it does not comply with the Law of the Sea and cannot produce any legal consequences for third States.”

“The European Council also reconfirmed the European Union’s position on Turkey’s illegal drilling activities in Cyprus’ Exclusive Economic Zone and unequivocally reaffirmed its solidarity with Greece and Cyprus,” the statement added.[33]

It is worth mentioning that Turkey’s claim of searching for gas reserves in the eastern Mediterranean is increasingly worrying for Greece and Cyprus.

France and Italy condemned Erdogan’s interference in Libya and his dispatching of Turkish troops to Tripoli to support militias and the Sarraj government. They also denounced Turkey’s plans to establish two military bases in Libya. Recalling the resolution NATO made at the 2018 Brussels summit on Libya, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said on May 14, 2020 that NATO is ready to help Libya in the security and defense fields if Sarraj requests.[34]

C-The US Position

The United States’ involvement in the Libyan crisis was merely for monitoring and countering terrorist activities. After the EU failed to resolve the Libyan crisis as some EU countries supported the militias operating in Libya, and following Russia’s entrance into the conflict, Washington hastened to find a decisive resolution to the crisis. Washington is concerned that Russia may establish a strategic presence in Libya — exceeding its initial aim, to military support the Libyan army. The Russian presence might be entrenched later by the deployment of air defense systems to Libya. Libya will probably acquire a Russian air defense system, posing a danger to NATO.

Gen. Stephen J. Townsend, commander of the US Africa Command (AFRICOM), cited US concerns over Russia dispatching 14 MiG-29 and Su-24 fighters to Libya. AFRICOM rang the alarm bell, accusing Moscow of destabilizing Libya, adding that Moscow is attempting to establish strategic presence points in southern Libya at the expense of innocent Libyan souls.[35]

VI-Russia and Turkey: Collision or Collusion to Divide Spheres of Influence

1-Libya in Russia’s Policy

After toppling Gaddafi in 2011, Russia’s role decreased in Libya. Russia’s President Vladimir Putin aims to achieve several long-term strategic goals: establish maritime influence in the Mediterranean, gain access to a large share of Libya’s oil and gas investments to strengthen Moscow’s hand to control global energy policies; benefit from Libya’s strategic location because it is a gateway for trade with northern and southern Africa; and secure a strategic foothold near NATO bases in southern Europe. If Russia manages to entrench its presence in Libya, the deep-water ports of Tobruk and Derna will be useful for Russia’s navy logistically and geopolitically, just like Syria’s Tartus port. Hence, Russia will have noticeable influence in Europe.

2-Dual Support

Haftar in 2015 visited and called on Moscow, asking for support. In exchange, he promised to grant Moscow the energy deals and port access it had coveted. Putin accepted his offer. Their cooperation started with Russia flying dozens of Haftar’s injured soldiers to Moscow for treatment. Russia provided Haftar with diplomatic support and military advice and increased the number of Russian military trainers in Libya.[36]

According to an article published in The New York Times on November 5, 2020, Russia had “introduced advanced Sukhoi jets, coordinated missile strikes, and precision-guided artillery, as well as the snipers.”[37] At the level of energy cooperation, a joint Libyan-Russian oil and gas project began operations in Benghazi in April 2020.[38]

Though Moscow is clearly in line with Haftar, it established ties with the Sarraj government, reflecting Russia’s duality in Putin’s regional strategy; establishing links with all vital actors to position Putin as a decisive decision maker.

3-The Future of Russia-Turkey Relations in Libya

The future of Russia-Turkey relations in Libya is dependent on whether there is direct/indirect military confrontation, or an understanding is reached on dividing spheres of influence. According to the first scenario, their interests may diverge or clash leading to confrontation and further complicating the Libyan crisis. A direct military confrontation may erupt between the pro-Turkish forces and pro-Russian forces, reigniting tensions which they had overcome in 2015 when both countries managed to evade a very dangerous diplomatic crisis to safeguard their mutual collaboration in Syria.

The second scenario is about finding a strategic Russian-Turkish self-serving partnership to divide the spheres of influence and secure respective interests in Libya. The Turks and the Russians showed us that despite the tensions and crises between them, they know how to evade direct confrontation. In recent years, their relationship in Syria indicates that Erdogan can work with his Russian counterpart despite their divergent military positions.

Findings

The Turkish intervention in Libya reflects the AKP’s vision; reviving the glory of the Ottoman Empire and expanding Turkey’s regional plan which it began following the Arab Spring. To achieve this dream, Tukey provided political and military support to the National Accord Government, aiming to destabilize the regional balance of power and benefit as follows:

- Turkey’s direct military intervention will escalate war between Libyan rivals, undermine the political settlement, and make Libya a gateway for Turkey to penetrate deep inside the Maghreb and the Mediterranean Sea.

- The UN mission failed to implement the Skhirat agreement, especially the items related to security such as dismantling militias and taking control of their weapons.

- Securing a foothold in Libya will provide Turkey with a stable and secure oil and gas source, which it really lacks. This will also help Turkey to create a new regional order and position itself as a powerful/unique player, so it can support Islamists and strengthen the Muslim Brotherhood in the Maghreb and Egypt.

- The maritime treaty will allow Turkey to control part of the Mediterranean Sea stretching from the Bosphorus Strait in southern Turkey to the Gulf of Sidra in Libya.

Endnotes:

[1] Henri J Barkey, “Turkey’s ‘Blue Homeland’ Doctrine on the Mediterranean Takes Shape in Libya,” Ekathimerini, June 23, 2020, accessed July 15, 2020, https://bit.ly/3fynmZ7

[2] “Controversy After Libya-Linked Turkish Plane Lands in Tunisia,” Asharq al-Awsat, May 9, 2020, accessed January 11, 2020, http://bit.ly/3ny7bhB. [Arabic].

[3] Ali Rajab, “Why Turkey Penetrates Into the Maghreb,” Islamist-Movements, February 8, 2020, accessed June 14, 2020, https://bit.ly/2Yx6bjn. [Arabic].

[4] Abdullah Hattos, “Does the ‘New Ottoman’ Pose a Real Threat to Morocco’s interests?,” Al3omk, March 6, 2020, accessed June 11, 2020, https://bit.ly/2zmyzfw. [Arabic].

[5] Basil Torjeman, “Trade Deficit Affect Tunisia-Turkey Relations,” Independent Arabia, February 12, 2020, accessed June 14, 2020, https://bit.ly/2MSJsJ8. [Arabic].

[6] “Strategic Objectives of Erdogan’s Visit to Algeria,” Spuntik Arabic, January 26, 2020, accessed June 1, 2020, https://bit.ly/2UwkNOY. [Arabic].

[7] Amar Lachemot, “The Algeria-Turkish Relations: The Historical and Geopolitical Dimension,” Ultra Algeria, January 26, 2020, accessed July 1, 2020, https://bit.ly/2BrlId1.

[8] “Foreign Minister Davutoğlu “21st Century Will Be the Century of Africa and Turkey,’” Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs, accessed January 11, 2020, http://bit.ly/39pA62k

[9] Jérémie Berlioux, “Turquie: Vers l’Afrique et au-delà,” Libération, February 18, 2019, accessed on June 14, 2020, https://bit.ly/3fqLRXV. [French]

[10] Rajab, “Why Turkey Penetrates Into the Maghreb.”

[11] Jassim Mohammed, “Does Erdogan Blackmail Europe?” EER, May 11, 2020, accessed June 21, 2020, https://bit.ly/3egId2u.

[12] “Erdogan Threatens: Road to Peace in Libya Passes Through Turkey,” al-Arabiya, January 18, 2020, accessed June 15, 2020, https://bit.ly/37ziLTw. [Arabic].

[13] “Turkish Intervention in Libya Puts Region on the Brink of War,” Asharq al-Awsat, January 4, 2020, accessed July 6, 2020, https://bit.ly/3f9NYja. [Arabic].

[14] OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin 2017 (Austria: OPEC, 2017), https://bit.ly/38A3ROF.

[15] “Shale Oil: Libya Ranked First in the Arab world and Fifth in the World,” Ean Libya, February 15, 2020, accessed December 3, 2020, https://bit.ly/36y3xz2. [Arabic]

[16] “Turkish Agency: Libya Oil Exploration Pays off Our Debts,” al-Arabiya, June 13, 2020, accessed June 16, 2020, https://bit.ly/3j85DtR. [Arabic]

[17] Fatimah Khadim Shirazi, “Objectives and prospects of Turkey’s presence in Libya – Part One,” IPSC, June 24, 2020, https://bit.ly/3j85DtR. [Persian].

[18] “After Borders and Influence: Turkey Looks for Libya’s Billions,” Sky News Arabia, March 8, 2020, accessed June 8,2020, https://bit.ly/3f3lBTg. [Arabic]

[19] “Turkey’s Long-Term Strategy in Libya,” The Libya Times, June 7, 2020, accessed July 14, 2020, https://bit.ly/2Cy27YS. [Arabic].

[20] Ibid.

[21] “Anadolu Agency: Libyan-Turkish Memorandum of Understanding for Security and Military Cooperation Comes Into Force,” Spuntik Arabic, December 26, 2019, accessed June 7, 2020, https://bit.ly/3onzbVW. [Arabic]

[22] Abdulmajid Abu’Ala, “Turkish Military Intervention in Libya: Its Forms and Implications for Terrorist Groups,” ACRSEG, January 12, 2020, accessed 15, June, 2020, https://bit.ly/2YBdjLF. [Arabic].

[23] “Turkish-backed Build-up Seen Targeting Sirte, Eastern Libya,” The Arab Weekly, December 24, 2020, accessed February 23, 2021, http://bit.ly/3uschRs. [Arabic].

[24] Abu’Ala, “Turkish Military Intervention in Libya.”

[25] “Libya: Is Erdogan embarking on an adventure fuelled by Syrians?”, BBC, June 9, 2020, June 22, 2020, https://bbc.in/2V87JiP [Arabic].

[26] “After Borders and Influence.”

[27] “Arab League Opposes ‘Interference in Libya’ After Turkey Accords,” Saudi Gazette, December 31, 2019, accessed February 24, 2021, http://bit.ly/3dBed3Y

[28] Yezid Sayigh “Is Cairo Going to War?,” Carnegie Middle East, June 22, 2020, accessed June 23, 2020, https://bit.ly/2BrR56V.

[29] “Analysis: Libya Turns Into a Treasure for Turkey and a Disaster for Egyptians and Tunisians,” DW, July 12, 2020, accessed June 14, 2020, https://bit.ly/30d0IPu. [Arabic].

[30] “After Erdogan’s Intervention. What is the Maghreb Countries’s Position on Libya’s Crisis?,” DW, January 30, 2020, accessed 23 January 23, 2020, https://bit.ly/2V9ogTP. [Arabic].

[31] “Arms Embargo | United Nations Security Council,” UNSC, [n.d.], accessed June 17, 2020, http://bit.ly/3aTdQ37.

[32] “Statement Attributable to the Spokesman for the Secretary-General on Libya,” UN, January 3, 2020, accessed February 24, 2021, https://bit.ly/2MlhpWf.

[33] “Answer Given by High Representative/Vice-President Borrell on Behalf of the European Commission,” European Parliament, March 20, 2020, accessed February 24, 2021, http://bit.ly/3byyMeP .

[34] “The EU Calls for Ceasefire and Expel of Mercenaries from Libya,” Sky News Arabia, June 10, 2020, accessed June 10, 2020, https://bit.ly/2BKP7yy. [Arabic].

[35] “What to Expect From Entente Between Moscow, Ankara in Libya,” Al-Monitor, June 5, 2020, accessed December 0, 2020, Via link https://bit.ly/3qCCrPa

[36] Anna Borshchevskaya, “Russia’s Growing Interests in Libya,” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, January 24, 2020, accessed February 24, 2021, https://bit.ly/3kfXJj2.

[37] David D. Kirkpatrick, “Russian Snipers, Missiles and Warplanes Try to Tilt Libyan War,” The New York Times, November 5, 2020, accessed February 24, 2021, https://nyti.ms/2OYKIP8.

[38] Borshchevskaya, “Russia’s Growing Interests in Libya.”