Next year will mark the 40th anniversary of the Iranian Revolution. The Iranians are anxiously watching a sharp economic downturn expected to start on August 6 as renewed U.S. sanctions go into effect, emerged from the tough stance the Trump administration adopted against Iran in 2018. The Iranian people had already suffered a deteriorated economy over the U.S. sanctions imposed before 2016. In May 2018, the United States decided to withdraw from the nuclear deal and re-impose new wave of crippling economic sanctions in two stages— on August 6 and on November 4. First-round targets Iran’s acquisition of dollar bank notes. Second round hits Iran’s oil sector. Iran has suffered, for four decades, an almost everlasting economic crisis. Over four decades, Iran could have enjoyed prosperity and spectacular economic expansion if it developed its natural resource wealth.

The study aims to provide an intensive analysis of the impact of the nuclear deal on the Iranian economy and living standards of Iranians during the two-year period. It also measures the impact of the Trump administration stance against Iran on the Iranian economy in the first half of the current year. In addition, it forecasts the future of the Iranian economy and the instability that may occur following the re-imposition of US sanctions. Finally, it unfolds the Iranian response to the emerging economic crisis and the available options to face the U.S. economic siege.

Historical background

Five presidents ruled Iran since the 1979 revolution, were each elected for two terms. Some were radicals, believing in self-development economy and in being independent of forces of economic globalization and exploitation by foreign businesses. While others were reformists, seeking to forge relationships with global businesses and support inflow of foreign capital to boost the national economy. However, the government intervention in the economy and the concerns over the inflow of foreign capital are the bedrock of Iran economic philosophy, gearing the decision-makers, elite politicians and clerics since the revolution.[1] If any president attempts to deviate from this philosophical framework, he pivots back around or simply avoids direct confrontation with it.

Iranian economy relies on three main pillars: First, the public sector is the most dominant contributor to the Iranian economy and mainly dependent on oil, mining, industrial, and service industry. Second, the cooperative sector plays vital and variant roles in Iran’s economy and politics and most prominently led by Bonyads; charitable trusts that report directly to the Supreme Leader and are not subject to parliamentary supervision. The largest institution in Bonyads is the Foundation of the Oppressed and Disabled or “MFJ”. Listed as the second-largest firm after the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC), MFJ employs more than 200,000 people. In addition, there are IRGC-owned companies of various economic activities all over Iran that report directly to the Supreme Leader. Third, the private sector is the least contributor to the Iranian economy because it can not compete with the public and semi-public sectors and suffer from the international sanctions which banned transactions with Iranian banks.

Over forty years, the Iranian economy has been through many ups and downs due to internal and external crises or due to direct and indirect forms of intervention in the region. Moreover, Iran has been facing international sanctions marked by turbulence and uncertainty. The toughest sanctions imposed on Iran were during Ahmadinejad’s reign, in 2012, which increased fluctuations in economic growth and human development indices.

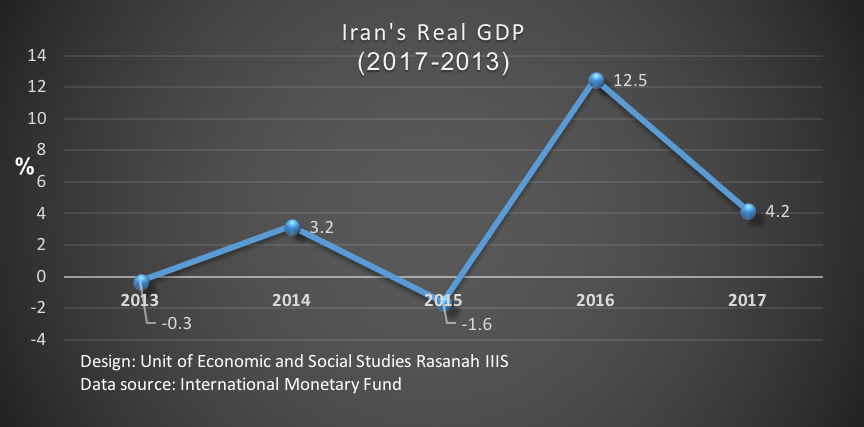

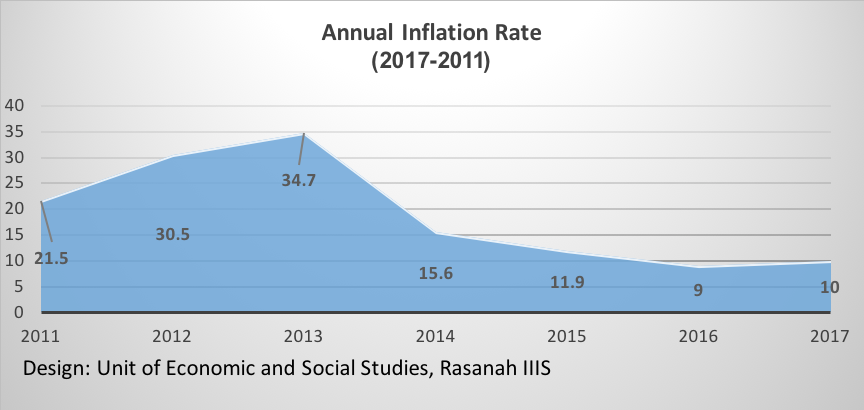

When Iranian President Hassan Rouhani came to office in 2013, the economic performance indicators were the worst ever in Iran with -0.3% GDP growth and very high inflation rate (35% reported in official statistics and %45 in unofficial sources). Iran reached almost a dead end. In 2016, the JCPOA 5+1 concluded with the Western great powers glimmered some light at the end of the tunnel. Rouhani was relying on the JCPOA to boost the Iranian economy, aspiring to find a way out of the financial crisis his county had been suffering. After the implementation of the JCPOA, oil revenues and foreign investment bounced back slightly, recorded a modest recovery less than expected.

In 2016, Iran’s economic growth was slowly increasing due to the relative oil contribution to the GDP and sluggish performance of non-oil sectors such as social development and unemployment adjustment policies. The internal crisis snowballed into protests over the deteriorating economic conditions in 2017. U.S. President Donald Trump threatened to pull out of the JCPAO and re-impose economic sanctions on Iran.

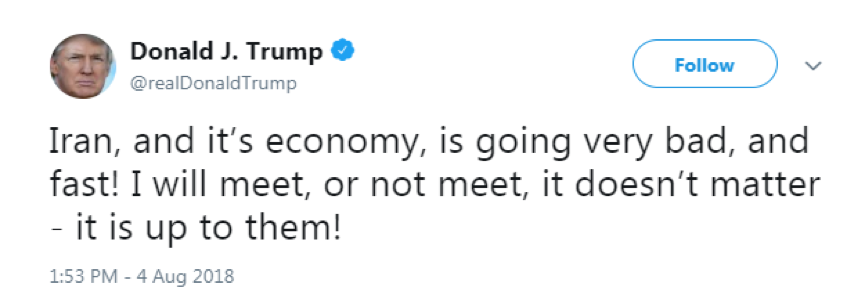

Following Trump’s decision to quit the nuclear pact in 2018, the United States re-imposed harsh economic sanctions in two stages in August and November, which will make the Iranian regime face another nasty crash in its unstable economy.

First: Post-JCPOA economic environment (2016-2017)

Evaluating the economic performance depends on a number of indicators giving a clear view of the economic growth such as real GDP,[2] unemployment, and inflation in addition to monetary and financial variables such as the budget deficit, the balance of payments situation, and public debt.[3]

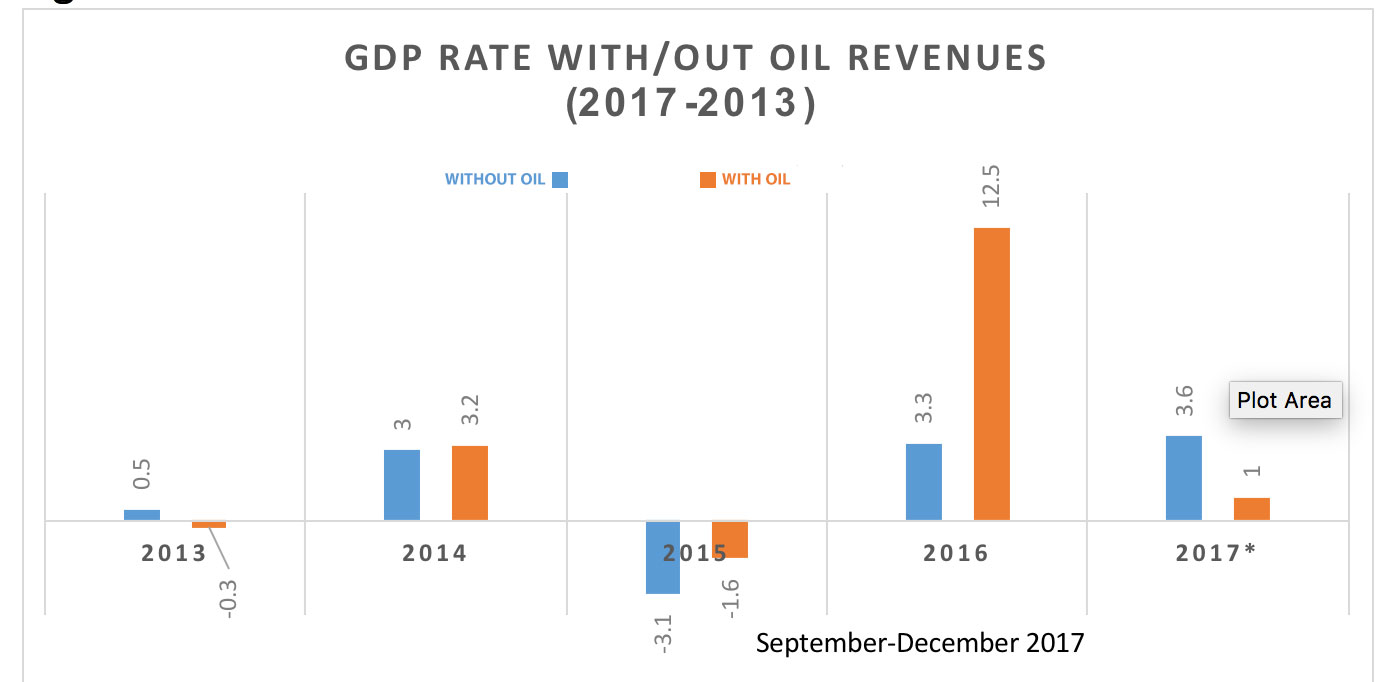

However, oil revenues boosted the GDP, but the Iranian people did not feel this economic bounce in their daily life. Iran’s economic situation during this period can be displayed as follows:

- Real GDP in 2016, including the oil sector, recorded high growth of 12.5% over the previous year (see figure 1). But the non-oil GDP growth reached only 3.3%. That shows how the Iranian economy became too dependent on oil revenues. It seems the non-oil sectors do not have the ability to jump-start the Iranian economy.[4] (See figure 2).

- The unemployment rate in 2016 was at 12.4%, according to the statistics of the Central Bank of Iran (CBI). In 2017, real unemployment -especially among youth and graduates, reported by unofficial sources, at 45-60% —though such increases were not corroborated by the official statistics.[5]

- During the past five years, the inflation rate was the lowest reaching only 9%. The Rouhani government recorded here a great achievement after years of skyrocketing prices (see figure 3). Relaxing sanctions played a vital role in smoothing the path for exporting final goods and raw materials. In 2017, Inflation slowly increased and put 1% higher than the rate recorded in 2016, according to official statistics. However, non-official sources claimed that the inflation in 2017 was higher. The unofficial statistics are in fact true if we consider that the Iranian government went on a wild money-printing binge, reaching an increase of 30%,[6] as well as, food and housing prices jumped by 50% in the same year.

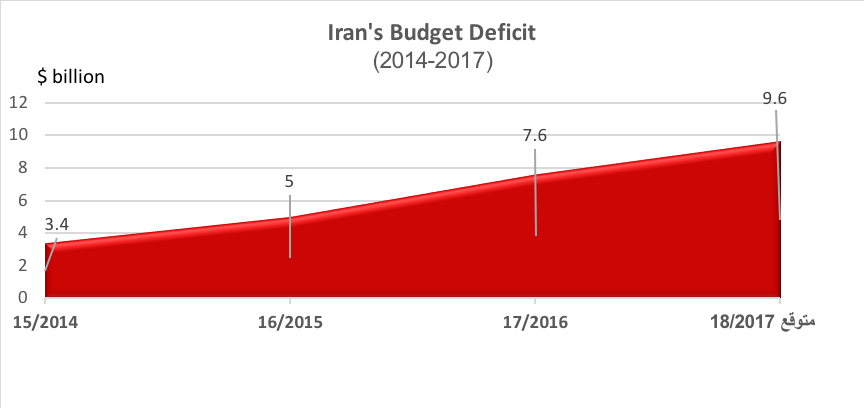

- The general government deficit has been increasing since 2014 with $7.6 billion in 2016 to $9.6 billion in 2017. The deficit is expected to worsen, as the actual income is lower than expected due to difficulties in collecting oil revenue payments and spending beyond budget. Budget policy is characterized by an increase in operating expenditures and decreases in investment, sending unemployment rates soaring.

- The current account balance significantly rose in 2016, compared with the percent in 2015. That is due to foreign capital inflow and lifting the embargo on oil exports. Although a foreign investment agreement of $12 billion was concluded in 2016, the actual investment gains did not exceed $2.1 billion[7] while the current account balance reached $16.3 billion in 2016, compared to $1.2. billion in sanction period, 2015. This sharp rise subsided within the first nine months of 2015 to $10.9 billion with a decrease of 8.4%, as compared with the same period of last year. The current account balance is based on real net exports of goods and services and transfer payments (e.g. foreign aid).[8] [9]

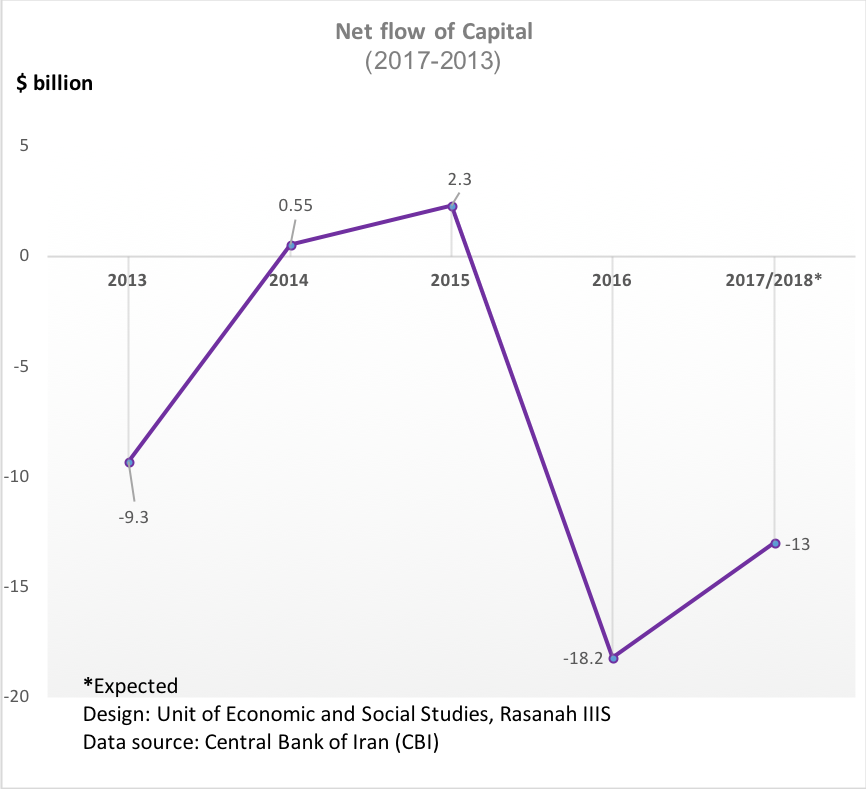

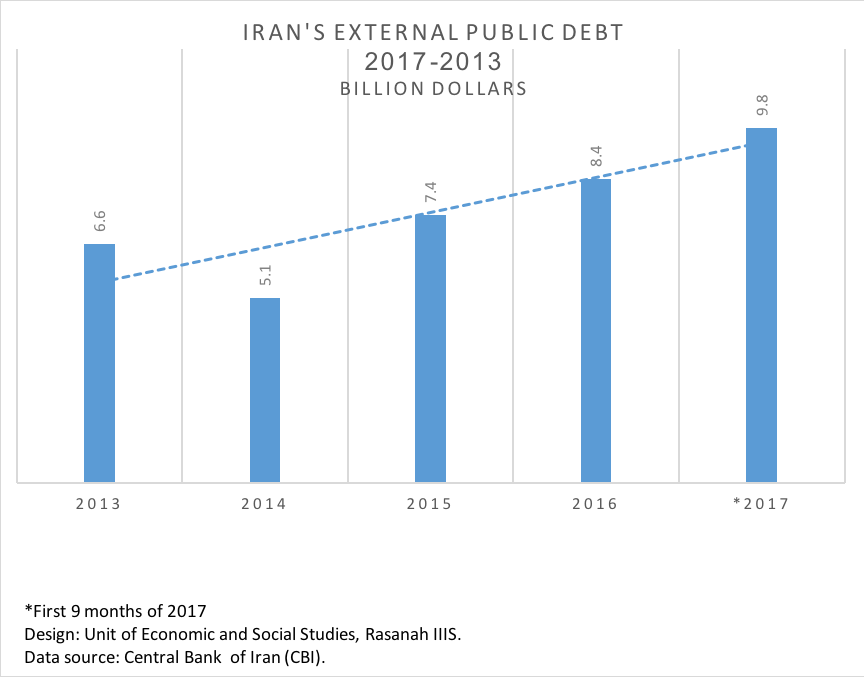

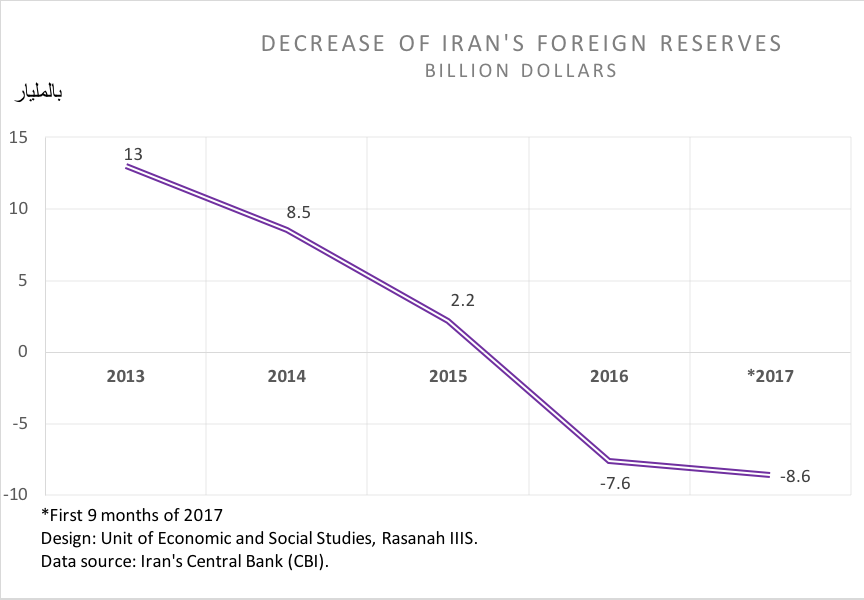

On the other hand, the capital account experienced a dramatic recession following the nuclear deal (see figure 6). It decreased to $18.2 billion in 2016 and $13 billion in the first quarter of 2017. This fall is due to the fact that the Iranian government maintained foreign currency at the fixed exchange rate, lower than its actual value. Iranian people save their money by purchasing real estate abroad or large quantities of gold, causing a rapid outflow of foreign currency.[10] Fixing exchange rates with the U.S. dollar made monetary reserve fall in 2016-2017 with a decrease of $6.7 billion and $8.6 billion respectively (see figure 8). - External public debt increased from $6.6 billion in 2013 to $8.billion in 2016, but it increased slightly in the first nine months of 2017 reaching $9.8 billion, according to the statistics of Iran Central Bank (see figure 7).[11] Though it is increasing but has not yet exceeded the risk-free The external public debt is only 3% of GDP, yet it places further pressure on foreign exchange rates when subject to payment of beneficiary’s debt.

- The monetary policy aims to stabilize the exchange rate and inflation in times of turbulence.[12] Iran’s monetary policy over the period 2016-2017 could not unify official and black market exchange rates. The official rate increased gradually trying to bridge the gap with the black market, however, the difference in rates remained constant. Moreover, the government managed to curb the 2016 inflation to less than 10% then it increased slightly more than 10%. This was accompanied with an increase in banknotes, a decrease in dollar resources, modest growth in non-oil sectors, and shrinkage in domestic products.

In a nutshell, most of the economic indicators in 2016 were good with a slight bounce due to the partial return of oil exports and foreign investments along with a weak contribution of non-oil sectors. Also, this year experienced a sharp fall in foreign exchange reserves, followed by an outflow of domestic capital. In 2017, as oil revenues diminished relative to GDP, economic performance and Real GDP declined. The balance of payments, budget deficit increased, followed by a jump unemployment rate and money-print without constraints. It is worth mentioning here that over the two years the total economic growth did not boost the living standards of Iranian people, it actually worsened their daily life; unemployment rate living costs increased. The monetary policy failed to stabilize the economic situation or at least slightly unify the official exchange and black market rates. All of this fueled the 2017 protests spread in various Iranian cities.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

| Figure 7 |

Figure 8

Second: Economic situation in the first half of 2018 after Trump’s decision to pull U.S. out of JCPOA

President Trump’s decision to pull the U.S. out of the nuclear deal and re-impose sanctions is a turning point in the Iranian economy. Before Trump’s decision went into effect, big foreign investments remained well-hedged and cautious to enter Iran’s market while other investments concluded after the nuclear deal were postponed.

Following Trump’s decision, foreign investment, oil revenues, exchange rates were all affected. Before studying thoroughly, the current economic situation in Iran, it is necessary to understand the nature of the U.S. sanctions re-imposed against Iran in two stages:[13] First is due to come into effect Aug. 6, including sanctions on the purchase of U.S. dollar by the Iranian government. The second batch of sanctions will be on November 4, targeting oil exports, ports and shipping sectors and transactions with Central Bank of Iran including SWIFT payment system.[14]

Several economic indicators varied in the first half of 2018, as compared with the average over the past two years. Over a relatively short period of time, the Iranian economy lost many economic gains reaped in the past two years, slipping down to a critical turning point, as follows:

- Oil exports decreased in the first half of June with 10%, recorded the largest decrease since Dec. 2016. Oil and gas majors like French Total and Royal Dutch Shell ceased imports of Iran’s crude oil. And many other international shipping firms halted shipments of Iranian oil. 70% of Iran’s oil is shipped by Iranian shipping companies, collaborating with Indian and Libyan companies. This dramatic change reflects the circumspection of new sanctions the U.S. will impose within few months and foretells the difficulties Iran’s oil sector has to face in the upcoming days if there is no way out.

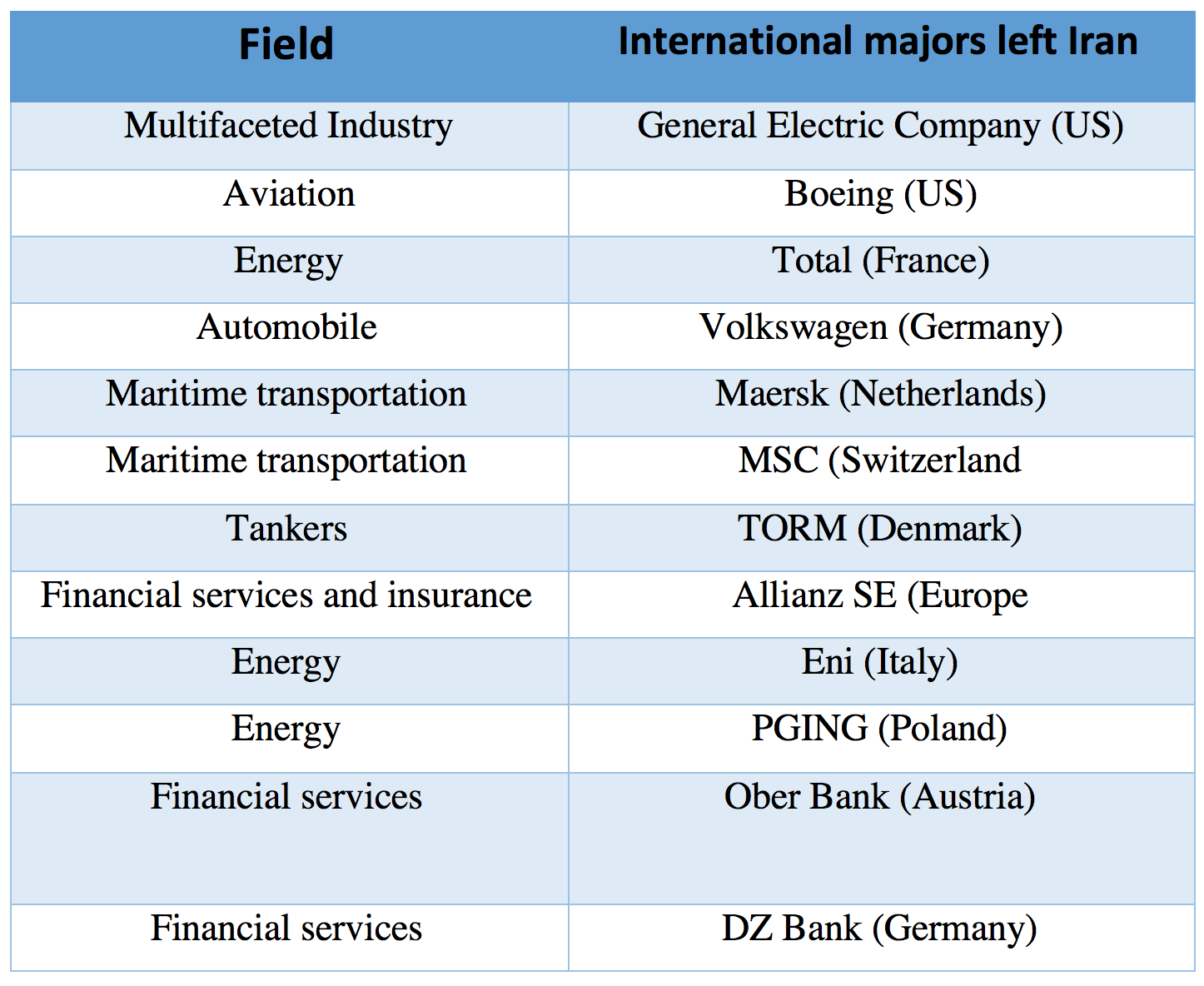

- International firms working in Iran announced leaving Iran within the 180-day deadline set by the United States, so they avoid paying fines under the U.S. sanctions and jeopardizing their existing interests with the U.S. markets. Most of these firms work in vital economic sectors in Iran such as oil & gas, aviation, banks, maritime transport, and industries (see table1). The U.S. aircraft giant Boeing canceled deals worth $16 billion with Iran. The direct foreign investment reached $5 billion in 2017, recorded the highest rate since 2012.[15]

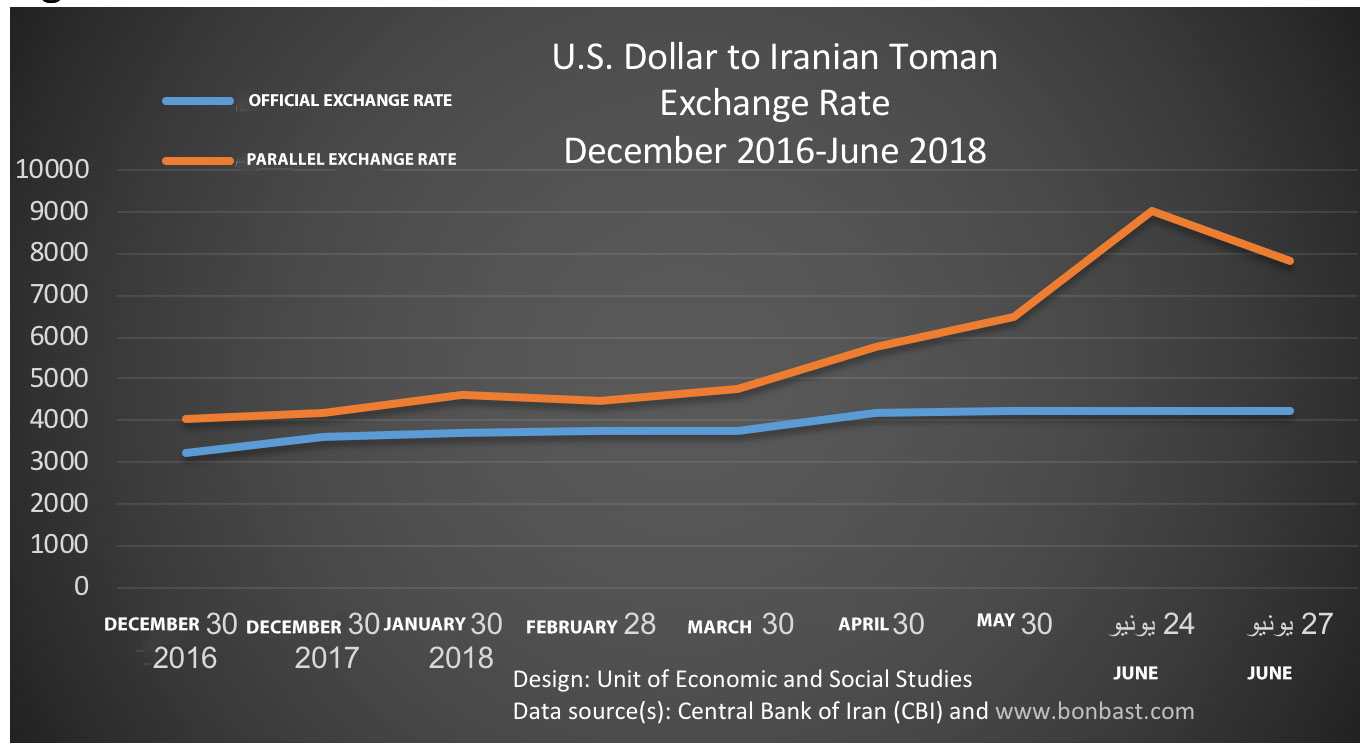

- Three rapid and sharp jumps in dollar exchange rate against the toman in the black market occurred in 2018: January, April, and June. The last jump rate was the most critical although the Iranian government banned owning foreign funds worth more than $12 thousand; increased the toman exchange rate against the U.S. dollar; and fixed at 4200 toman/$1. In the first half of 2018, the gap between the official exchange rate and the black market yawned further — the official rate unexpectedly fell to just double the parallel rate. The U.S. dollar-to-toman exchange rate jumped to 110% in the black market: 4200 toman/1$ in 2017 to 900 toman/1$ on 24 June 2018 (see figure 5).[16]

- Social instability, caused by never-ending protests over deteriorating living-standards, first started with teacher protests in Yazd city, followed by the protests of steelworkers in Ahvaz and railway workers near Tabriz city.[17] The protests rose up in late 2017 and early 2018 against the same problems and spread across 85 cities. The protestors were angry at their country spending their money in Syria, Yemen, and Iraq while they are starving at home. The protests emerged again in June led by bazaar merchants who are affected badly by the sharp decline of the exchange rate and U.S. dollar shortage, causing prices to skyrocket and demand goods fall.

- Iranian elites and clerics bashed the performance of the government economic team. They ratcheted up their criticism of President Rouhani, calling on their leader to testify before parliament to explain why the economy deteriorated this far. Iran Supreme Leader Ali Khomeini criticized the economic downturn, calling on the government to return to the resistive economy and urging people to be patient and hold on. Apparently, semi-government firms of the IRGC such as Khatam Anbiya and many other state-fund organizations affiliated with the religious or military authority are expected to engage in economic activities.

Table 1: International Firms left Iran’s market

Third: Futuristic reading on Iran’s economy and the available options for the regime

The Iranians cannot see their future without fear. They are not exaggerating nor to be blamed either. They have suffered harsh living conditions resulting from crippling economic sanctions. The Iranians and observers of the Iranian affairs wonder whether the Iranian economy would survive this time or the old crises and economic ramifications would rise again, leading to the final collapse of the whole economy. Would the tough stance of the U.S. administration against Iran make Iranian decision-makers change their behavior in foreign affairs? Expecting the future of a crisis-experienced economy is not easy. Laying down various scenarios can help find stabilization for the upcoming economic fluctuations in Iran.

- The first scenario: the very acute economic situation

Perhaps those forecasting the most optimistic scenario for the future of the Iranian economy recognize the difficult economic situation in the future, not to mention the difficulty of the current situation, after the US withdrawal from the nuclear agreement has concrete consequences on the ground. Also, sanctions have not taken effect yet as we explained earlier. Now it seems Iran is heading for a stage in which the economic performance will see a severe weakness in terms of the overall economic indication, decline in financial performance, and rise in the day-to-day cost of living. This speculation emerged based on a host of indications:

- Crude oil exports drop: A report by the British oil industry giant British Petroleum (BP) suggested that the Iranian crude oil exports may fall between 300,000 barrels and one million barrels per day in the future (decreased by 143,000 barrels per day in the first half of June 2018).[18] In a statement, Iran’s Oil Minister Bijan Zanganeh in June, acknowledged there are problems relating to transporting and securing the Iranian oil, asserting there is difficulty in generating revenues from oil exports, although US sanctions have not yet taken effect. Some very simple mathematics will indicate that Iran’s oil exports drop from 300,000 to one million barrels a day will lead to government revenues’ drop by between $ 22.5 million and $ 75 million per day at current oil prices (within $ 75 a barrel), taking into account the orientation of oil producers, inside and outside OPEC such as Russia, to increase the oil output globally. This increase may lead prices to fall. At this point, Iran will be faced by two challenges: lack of oil exports and a possible decline in future oil prices.

- Impact of oil exports’ decline on the GDP: there is a clear relationship between the continuation of oil exports to the outside world and the acceptable growth rates posted by the Iranian economy. In 2012, the growth of the oil sector declined to -36.5%. The Iranian economy grew by -6.8% in the same year.[19] When the nuclear agreement was implemented and oil exports rose, the economy achieved record growth rates, as we have seen. That’s why US-based Fitch’s BMI forecast a weak GDP growth rate of 3% by the end of the year and less than 1% in 2019.[20] The economics professor at the University of Virginia Tech, Javad Saleh Esfahani, also predicted that the economy’s growth rate will remain low in the coming years. The economics professor at the University of Virginia Tech, Javad Saleh Esfahani, also predicted that the economy’s growth rate will remain low in the coming years.[21] The impact of lack of financial resources on the budget deficit and cost of living: The decline in government financial revenues will limit their ability to implement the annual budget plans, and will be forced to reduce expenditures, possibly at the expense of social and development programs, or deficit spending. They will resort to internal or external borrowing. Or may they resort to the worst means ever: unchecked banknote printing – as it was the case last year – bringing about more inflationary pressures that increase the Iranians’ day-to-day cost of living. Oil revenues are the biggest financial sources of Iran’s foreign currency stockpile. The lack of this resource will affect Iran’s credit rating and the foreign exchange rate against the toman, leading to more inflationary pressures and higher living costs if the Iranian state does not find alternatives to preserve its foreign currency sources.

- Significant trade losses expected if Iran’s most important trading partners – especially from the EU – decide to stop or reduce trade with Iran in order to preserve their broader trade interests with the United States. If only the European partners decide, for example, to align themselves with the US, it means that Iran will lose vital imports from the EU, which hit $ 10.8 billion in 2016, mostly machinery, industrial spare parts and technical products.[22] This will be seen in more factories non-oil sectors’ shutdowns, job losses, and production cuts.

- Capital flight and the inability of domestic investment to push growth up: Trump’s hard-line tackling of the Iranian file led to the flight of a huge amount of capital outside Iran, amounting to about $ 13 billion in the Iranian year 1396 (March 2017 / March 2018) according to the Research Center of the Iranian Parliament. Other sources have reported as much as $ 30 billion flew away from Iran[23] so far, including the actual or potential capital. Local investments are not dependent on economic growth. The rise in the domestic interest rate (above 20%) has led to a decline in fixed investment to 20% of GDP, a 10% below the rate required to bring down the unemployment rate, while government investment with less than 3% of GDP is barely enough to maintain and repair available infrastructure. “The banking system is stumbling and shackled with bad debts and has been unable to pump investments since 2012,” says a professor of economics and a fellow of the Brookings Institution of Iran, Javad Saleh Asfahani.[24]

Bijan Khajehpour, an Iranian economist, says that the current internal situation of the government’s low economic performance and the increasing pace of protests will boost the likelihood of “economic crises” with unprecedented social and political consequences. He cites the recent wave of protests by Bazaar traders as proof of what can befall Iran in case the government does not intervene. To avoid economic collapse, the government should stop playing the victim’s role – the government’s shifting the blame to networks of corruption for sabotaging the economy – and begin immediately organizing markets based on economic rules and a long-term vision.[25]

Sanam Vakil, a British academic and a fellow of the British Chatham House Institute, sees the future from a perspective worth reflecting. The Iranian regime has been accustomed to critical crises since the Iranian revolution in 1979. It can be said that Tehran survived the 1980-1988 Iran, the death of Khomeini in 1989, and decades of confrontations with the international community over the nuclear program from 2003 to 2015, due to the united political elites – to some extent – in the face of external challenges. But the situation today is different, and the unity among political elites seems to be hanging in the balance. Political elites are fighting not only for the future of the Islamic Republic but also for their position. Fackel, a specialist in Middle Eastern studies, argues that the continuation of the ideological struggle that has been going on for years over the identity of the economic system between Iran’s competing rivals, the radicals, and reformists, will eventually lead to a new crisis and stagnation, or lead to the development of the Iranian state in case the regime managed to turn the foreign pressures into gains and mobilized elites’ ranks for a genuine economic and political reform.[26]

- The second scenario: Could the Iranian economy collapse?

Before embarking on this scenario, the term “economic collapse” should be clarified and distinguished from the concept of “economic crisis”. The concept of “economic collapse” is defined as a severe state of economic recession (the recession is a depression of two years or more. It is characterized by a decline in production rates and increased unemployment) that will continue to decline for years and perhaps for decades. The macroeconomic collapse has a host of characteristics such as sustained recession and stagflation, hyperinflation, civil unrest, high levels of poverty and disruption of financial markets.[27] Among the signs of economic collapse are compulsory holidays for banks to control withdrawal of funds, strict controls over capital and its transfers, and the overthrow of stable governments.

The so-called “Great Depression” of the US economy in 1929 was the most landmark economic collapse in recent economic history. It happened after the fall of the stock market and the economy’s recession[28] (for 3 years or 3 years and a half) where nearly 25% of US GDP meltdown). Poverty and unemployment rates reached unprecedented levels (24%). Also, there is the collapse of the Argentine economy, which lasted for years during the 1980s and 1990s. The economy there has repeatedly recorded negative GDP, the value of the local currency has plummeted, and inflation has risen at a staggering rate of close to 5000 percent in the 1980s.[29]

The concept of collapse is different than the concept of crisis in terms of the associated effects, the duration thereof and impact on society. For example, the global financial crisis of 2007-2009 lasted less than two years, and the US GDP, for example, posted negative rates for a year and a half (5%) while unemployment surged to 10%.[30]

Back to the Iranian situation, Columbia University associate professor Richard Nephew sees the idea of Iran going to the brink of economic collapse is “exaggerated”. He argues that this speculation stems from the belief that such a collapse would lead to a revolution which will lead to forging positive ties with the outside world after the economic drop that will lead to a revolution that ousts the regime from within.[31]

Based on the foregoing we conclude that the concept of economic collapse, from a purely academic perspective, does not apply to the Iranian case at the time being. This is unlike describing the looming future economic crisis that could happen due to the regime’s countermeasures. But this means also that the economy may be heading for collapse in case the following theorems, or some of them, happen on the ground:

- Moving ahead with funding huge military expenditures abroad at the expense of economic reform and the balance of the financial and monetary performance of the state, putting into account that $ 350 billion is the estimated total expenditures incurred by Iran as a result of its military and political intervention in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Lebanon to date. Therefore, the Iranian economy is not expected to achieve financial or monetary stability if increased spending on conflicts beyond borders continues (128% increase in spending over the past four years).[32] At the same time, financial resources are eroding after the US sanctions.

- The duration of the crisis: i.e., if the crisis dragged on for years and indicators of the economy (mentioned above) and living conditions worsened/declined year after year and the government’s interventions did not pay a dividend and failed to curb the deterioration of the economic performance in the short-run.

- The continuation of the American blockade and the global boycott of the Iranian economy. But this depends on Iran’s changing of its foreign policy behaviors and boosting cooperation with the outside world for this siege to come to an end. In the above-mentioned points, we reviewed the impact of the regime’s openness, and the lack thereof, on the level of the economic performance.

- Unrest at home has surged as well as social woes, given the youths makeup about half of the Iranian society, and this society is plagued with high rates of unemployment and poverty. this could to the outbreak of a popular uprising in the end that could oust the deep-seated regime, which is not in tune with the ideas of those youths who are open to the world despite the restrictions the regime is placing on them.

Some analysts tend to bet on the reaction of society, especially youths, in deciding the fate of the economy. In other words, they bet on the people’s inability to endure economic additional pressures, after showing patience towards a weak economic performance for 40 years after the 1979 revolution. Since Khomeini had promised to achieve social justice, nothing has been made so far. There has been a large disparity in the distribution of income and wealth. For 40 years, the GDP growth rate was weak, at an average of 2% per annum, lower than the annual rate of population growth (2.4%) during the same period. Also, GDP per capita declined by an average of 0.4%.[33]

On the other hand, the United States wants to exert pressure on Iran by all possible means to bring about a change in Iran’s foreign policy as a condition for resuming negotiations and lifting the embargo on Iran’s economy, or strangling it on the domestic and foreign levels until it reaches its desired goal.[34]

- The options that the Iranian regime has in the future

The options before the Iranian regime may include a wide range of economic and political solutions/tricks that the regime can depend on one or more of them to face the economic repercussions of the US sanctions. They can be summed up as follows:

- Making political concessions to the US administration in the last minute and returning to the negotiating table. This is known as the brink policy the regime resorts to when things get complicated and reach an impasse. It implements the policy to prevent the regime’s fall or any internal collapse. After the revolution, the Iranian regime resorted to this policy more than once throughout its history. This tactic is backed by an Iranian activist: daughter of one of the most prominent figures within the regime: Faeza Hashemi Rafsanjani. She saw it deems necessary for the regime to implement non-economic solutions, notably changing the Iranian foreign policy. She also declared support for any possible change that may happen as the time passes, given if things have gone worse and reached the brink for the country not to suffer more harm or be liable for collapse.[35] “We used to solve the problems after reaching critical points, as we did when we released the American hostages in 1981 and accepted peace with Iraq in 1988,” Rafsanjani said. “We will do the same with Trump. She noted: “Our Shiite understanding allows us to modernize Islam. So why don’t we change or foreign policy.” It seems that option is highly likely in light of the historical experiences of the regime when it comes to sanctions as the regime accepted to resume negotiations that led to signing the nuke deal in 2015. This happened after the Iranian economy and people bore the brunt of sanctions.

- Adopting urgent economic reform programs. They are either real reform programs or ones aimed at gaining public support and maintaining the stability and security of society in the first place. In other words, these reforms may be just sedatives to lull the situation such as such as the cash subsidies to the poor that were endorsed by former President Ahmadinejad during the economic siege. But when president Rouhani came to power, he scrapped it to cut spending. They may also disburse unemployment benefit for the youths to contain their anger. Of course, the government’s budget is shackled enough with financial burdens. Thus, these temporary solutions will be at the rational economic performance. They will lead to increase these burdens in the future, delaying the effective solutions to the following governments. Furthermore, the government may turn to the outside world for borrowing or increase the smuggling activities to maximize the resources of the state. The regime may adopt real economic reform programs aimed at revitalizing the economy, but it will not gain the popular support required in the coming period. The regime may layout programs to follow specific fiscal or monetary policies, such as reducing public spending to the maximum and increasing the state’s financial revenues Increase taxes (eg. value added tax) or further reduce subsidies (energy and others).

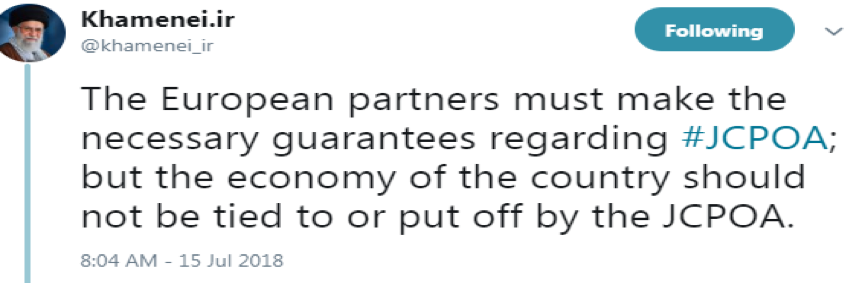

- Revisiting the resistance economy, which is preferred by the supreme leader Khamenei. He called for implementing it in 2012 in response to the Western siege to Iran. It is based on encouraging the domestically-manufactured products and abandoning the imported items and foreign investments. This means a bigger role for the government and the quasi-government institutions in the economic activities. This will further marginalize the private sector in the future. The semi-state institutions are commercial establishments affiliated to the religious authority or the so-called Bonyads along with the IRGC-run institutions. They are many. One of these institutions is Khatam Anbiya Construction Headquarters. It owns about 300 firms working in the fields of oil, gas, petrochemicals, industry, mining, and infrastructure. The firm is employing tens of thousands of workers. This would be added to allegations related to the involvement of the IRGC-run firms in illegal activities such as smuggling goods, arms, oil, and others.

- Circumventing sanctions to increase the financial resources and alleviating the impacts of the US blockade on its economy. The regime may use means such as smuggling foreign currency through agents, traders or supportive countries. It may also sell oil in exchange for US dollars via a neighboring nation or selling it at a lower price in return for getting cash payments. Or may it resort to trading goods and services with the Iranian oil? There are countless means indeed. Such tricks were exposed after reports of arresting managers of Iranian firms who were bearing forged passports of Comoros so that they could establish international commercial firms and transfer money away from the US controls.[36]

- Desperate threats to the security and stability of neighboring countries and perhaps the world: The Iranian regime sometimes resorted to threats by saying it will inflame terror, threatening to close shipping routes to international trade or harassing international merchant ships passing through the international corridors. Furthermore, the Iranian president Hassan Rouhani, backed by the chief of Quds Force Qassem Suleimani, threatened to flood the region with drugs, block regional countries from exporting oil and close the Strait of Hurmuz.[37] In other words, the regime hints at the possibility of threatening security and stability of the entire world, especially the industrial countries. Although the possibility of Iran closing the Strait of Hurmuz is ruled out, policy-makers there will be heedless of the fact that they are waging a war against the whole world, giving the international community a case for using force to restore stability for the energy sector globally.[38]

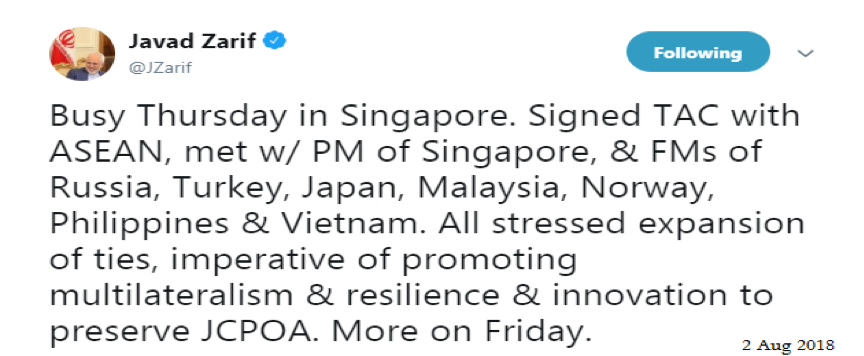

- Depending on allies to gain economic support and solidarity: this will be whether from neighboring countries such as Iraq, Qatar or Turkey, or from trade allies such as the European Union and the most important buyers of Iranian oil, such as China, India, South Korea and Japan, or perhaps political allies such as Russia.

But in practice, what can each of the above-mentioned allies do to support the Iranian economy in the coming period?

- Qatar, Iraq, and Turkey: Commercial and political relations between Qatar and Iran have grown following the Gulf States’ boycott since 2017. Trade relations between the two countries have flourished during the first three months of this year by 214%. There were also exchanges of visits between senior officials of the two countries as well as mutual coordination at highest political and economic levels (Emir of Qatar and President of Iran) to raise the volume of trade to more than 5 billion dollars and facilitate business between the two countries. Although this is possible over the years, there is little hope to count on increasing trade volume between the two countries which reached about $ 250 million in 2017) in easing the US embargo on the Iranian economy in the short term. To Iran, Qatar may be reliable in terms of its huge financial resources as it is the world’s number one exporter of LNG. It is culminating colossal amounts of money if compared to its scant number of populations. Thus it can generously back Iran through non-repayable grants, soft loans, bank deposits for long terms with political aims. Qatar did this before when Egypt’s foreign exchange reserves declined to alarming levels in 2013 under Mohammed Morsi of the Brotherhood. Qatar gave the government there $ five billion, four of them were deposited to the Central Bank, and the other $ 1 billion was a non-repayable grant.[39] The Egyptian government paid back all this money at the request of Qatar following the downfall of the Muslim Brotherhood’s rule in 2013. As for Turkey, the trade exchange between it and Iran is deep-rooted and varies widely from that with Qatar. Turkey imports about a third of its energy needs, especially natural gas comes from Iran.[40] And Iran imports industrialized Turkish products. Therefore, after the US withdrawal from the nuclear agreement, both the Turkish President and the Minister of Economy were quick to stress the continuation of economic relations between the two countries. “Despite the decision of Washington, Turkey will maintain its commercial relationship with Iran and will not respond to anyone in this regard,” said Turkish Economy Minister Nihad Zibekji.[41] The two countries are seeking to sign trade agreements, exchange currency and raise the volume of trade between them to $ 30 billion. But if we look at the volume of trade exchange between the two countries, we can see a significant decline in recent years, reaching about $ 9 billion by the end of 2016 down from $ 20 billion in 2012. However, the recent devaluation of the Turkish lira against the US dollar may serve to boost its export abroad. But with the recent dollar shortage in Turkish markets, it will be difficult for Iranians to smuggle the dollar through Turkish banks and front companies, as was the case during the years of blockade before signing the nuclear deal to secure dollar resources for the regime.[42] The Iraqi-Iranian cooperation is at a critical stage in its history after the great rapprochement following the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime. And signs of this new relationship are already taking shape at the present in light of the recent developments on the Iraqi arena such as the demonstrations against the Iranian intervention in Iraqi affairs and the use of Iranian electricity for political leverage on Iraq. Yet there is a growing Iraqi rapprochement with its Arab and Gulf neighbors and the Iraqi economy’s need for boosting cooperation with the regional and global powers, not being at odds with them as the war-torn country seeks to aid in reconstruction efforts after years of fighting ISIS. Therefore, Iraq is unlikely to engage in alliances that harm its interests with the international community for the sake of Iran by smuggling the Iranian oil through the Iraqi ports. But Iraq will not prevent the Iranian militias from attempting to find loopholes to alleviate the US pressure on the Iranian economy as long as it is present inside Iraq.

- Trade with European allies: EU countries are Iran’s fifth largest trading partner (measured by total exports and imports between the two countries) and provide most of Iran’s needs in civil aviation, automobiles and spare parts. Therefore, Europe adhered to the nuke pact and called on the US to exempt its firms from the sanctions related to trade with Iran. The US administration has refused to grant this exemption so far. Even if the US agreed to grant this exemption, will this exception compensate European companies for straining their trade interests with the US government? There is nothing logical for the big European companies – even if their governments have stuck to the nuclear deal – to cede making a profit from the world’s largest economy, whose volume amounts to $ 20 trillion, for the $ 400 billion, or a little bit more, Iranian economy whose future is volatile. The majority of European companies that have business in Iran transfer their money in US dollar, which puts them under US sanctions when dealing with the Iranian side. Total, for example, which rushed out of the Iranian market after the US withdrawal funded 90% of its work through US banks, and 30% of its investors are US citizens.[43] Based on the fact that capital is agnostic, it is unlikely that Iran’s dependence on most of the European partners, or even all of them, will work in case the US shifts its position on the Iranian regime.

- Economic cooperation with Russia: the Russian-Iranian cooperation is stronger in the political aspects than in the economic ones. Most of the trade exchange between the two countries has focused on the military field in the past years, but even after the lifting of the Western sanctions on Iran, the volume of trade between the two countries did not exceed $ 2.2 billion by the end of 2016. The agreements whereby Iran could trade oil for Russian goods and equipment may go into force in the future on a bigger scale, keeping the reservation on quality and technique of this equipment if compared to that of Europe. This means that the Iranian consumer and manufacturer are no longer having the freedom of choosing among alternatives. Some voices speculate that Russia will boost dependence on the Russian civilian jets, of Sukhoi category, instead of the West-manufactured ones. But if we put into account that these jets have a short-range if compared to the European ones and some of its spare parts are made in the US, which will definitely lead to sanctioning the Russian firms. It should be noted that the Russian economy is the other has enough crises with an economic blockade of the United States and European countries over Russia’s intervention in the recent US presidential elections and Russia’s annexation of the Crimea in Ukraine. Russia needs to cooperate with the US to ease the siege imposed on the Russian economy.

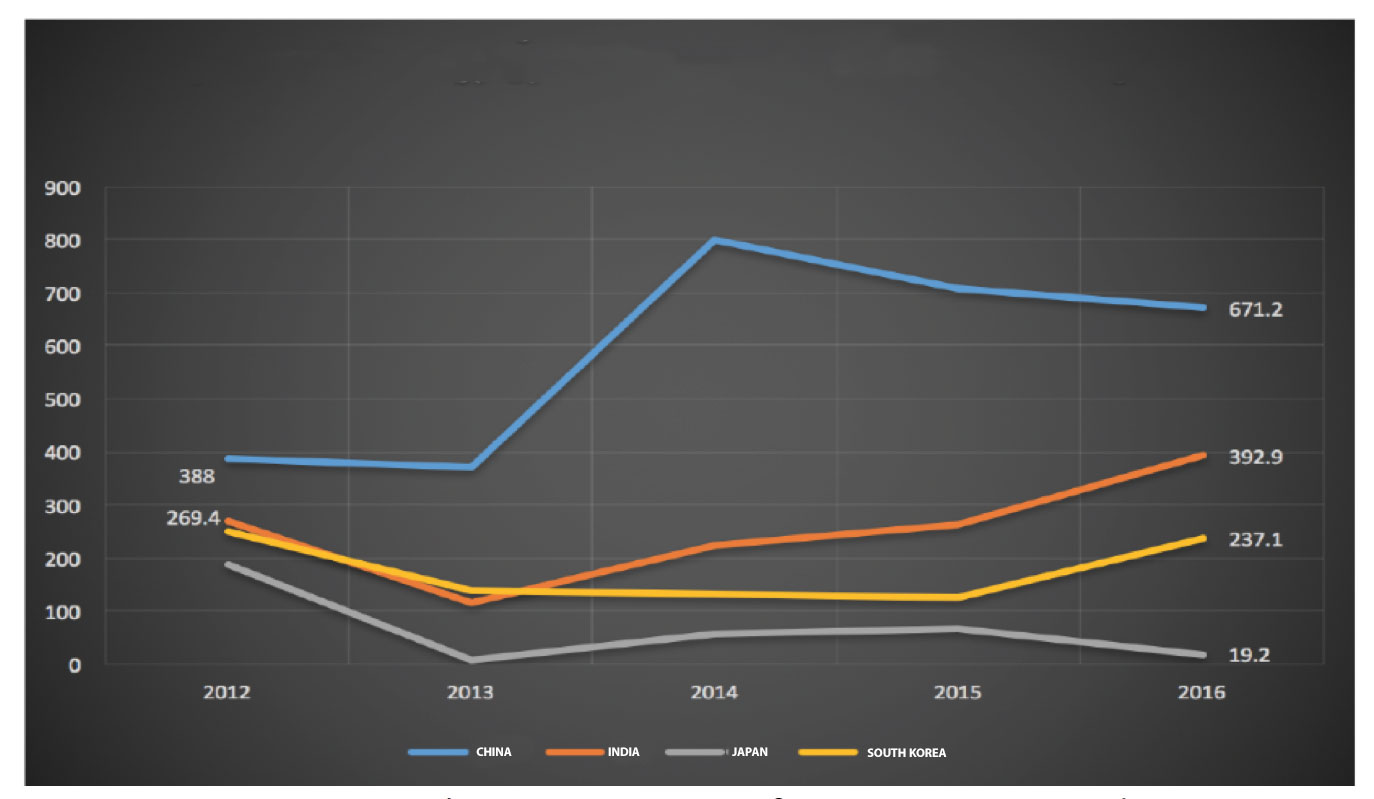

- Most of Iran’s oil importers: China, India, South Korea and Japan. These countries are the largest importers of Iranian crude oil and the most important financial supplier to the Iranian state. Before the US sanctions were reinstated, they imported more than two-thirds of Iran’s crude exports. The other one-third is exported to European countries. Therefore, these countries’ purchase of the Iranian oil is a prime aim for the Iranian regime in the coming period. The president of the US called on these countries to reduce Iranian oil exports to zero, and some of them, such as India, have already reduced their oil reserves and sought other alternatives with unconfirmed statements that India’s import of Iranian oil will be halted completely by November 2018.[44] As to China, which is the biggest importer of the Iranian oil in Asia, has not declared so far a clear policy towards importing the Iranian oil. But it is likely that it will tend to take measures that secure its massive economic interests with the US in light of the recent trade standoff over tariffs. China’s total trade with Iran is only 1% compared to the rest of the world. In other words, China will reduce, not stop, the imported oil from Iran as it was the case before signing the nuke pact (figure 9) and due to the high costs of shipment between the two countries. As to the means of payment, there is no problem in this regard between the two countries. Payment may be through postal transfers, in cash or euros.[45] South Korea and Japan are very likely to reduce their imports of Iranian oil to big levels as it happened in 2013 (see figure 9) in order to preserve the deep-rooted economic ties with the US and the interests of the major Korean and Japanese firms working on the US market such as Toyota, Hyundai and other companies working in industry and technology. In 2013, Japan’s import of Iranian oil fell to almost zero after tightening sanctions on Iran, compared to 200,000 barrels per day in 2012. South Korea’s and India’s imports of oil have fallen from slightly above 250,000 bpd to almost 100,000 bpd over the same period.[46] As to South Korea, its imports of the Iranian oil declined in July 2018 by over 40 percent, the lowest since 2015. This comes amid speculation that it will totally cease imports as it is not sure it will get exemptions from the US sanctions on the buyers of the Iranian oil.[47]

Figure 9: The Iranian oil exports, measured by 1,000 bpd in April each year.

Source: International Institute of Iranian Studies, 2016, https://goo.gl/vy8oNZ

Conclusion

In a nutshell, the Iranian economic massive capabilities may put Iran among developed countries. Iran has many natural resources including oil, gas, workforce and various capital assets, but these capabilities did not consist any integrated economic and human development renaissance, a matter that the Iranian decision-makers should heed for instead of directing the financial wealth of the country for non-state groups and militias to destabilize the region.

Over the last 40 years, the Iranian GDP has increased by 2% per year, which is less than the growth of population (2.4%). In other words, the expanding economy is not commensurate with the growth of the population and the GDP per capita decreased by an annual rate of 0.4% and the latter is an indicator of productivity and standard of living development of the Iranian individual for nearly 40 years.