The 2021 Iraqi parliamentary elections drew attention from domestic and external actors. This attention was because of Iraq’s centrality and geopolitical significance in their strategies and in light of the cutthroat contest between two opposing domestic currents over the future of Iraq. The first current supports the transition towards establishing a nation-state that enjoys independence, sovereignty and edges closer to the Arab sphere. On the other hand, the second current clings to the “non-state” idea, and seeks support from Iran. Iran exerted efforts prior to the Iraqi elections to create strong partisan alliances in order to enable the pro-Iran political wings to form the biggest parliamentary bloc. This would allow them to have a significant say in the designation of a new prime minister to serve Iran’s agenda in Iraq. In response, regional and international actors exerted efforts to curb Iran’s influence over the election results to prevent Tehran from securing greater domination over the Iraqi equation and to push Iraq towards meeting the aspirations of its people through resolving chronic domestic crises such as the electricity crisis; fighting corruption; charting a balanced path in its foreign relations; and transitioning the country towards full sovereignty and independence.

The election results will have a significant impact on the balance of power equation whether inside Iraq or between regional and international actors. This is because the results will lead to the establishment of new blocs and if a bloc has the majority of seats, it will be in pole position to designate the prime minister and decide whether or not to transition the country to statehood or maintain the “non-state” situation. The election results will be instrumental in outlining Iraq’s political map in the coming four years. The study, therefore, analyzes the election results, forecasting two potential tracks that Iraq might pursue. This is in addition to shedding light on the implications of the elections for Iran’s future role in Iraq through discussing the following: the electoral environment, Iran’s central role, the map of political alliances and contesting parties, electoral issues, election results, seats won by each alliance, significations of the shift in the electoral landscape and the impact of the election results on Iran’s role in Iraq.

- The Parliamentary Electoral Environment and Iran’s Pivotal Role

The early parliamentary elections were held at a time and in an atmosphere different from those held in the past. In 2005, the elections were held under a transitional government two years after the US invasion of Iraq. The 2010 elections were influenced by the efforts of Iran and its allied factions to strengthen sectarianism inside Iraq. In 2014, the Iraqi elections were held following the US withdrawal and the outbreak of the Arab popular uprisings. The 2018 elections were held following the Kurdistan independence referendum which was held in September 2017, and after the announcement by former Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi in 2017 that ISIS had been militarily defeated and the Iraqi Parliament in 2016 approving the law to integrate the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) into the regular Iraqi army.[1] All electoral cycles have been characterized by instability which has been part of the Iraqi scene ever since Iran started to intervene in the country following the US invasion of the country in 2003.

At home, the 2021 parliamentary elections were held against the backdrop of three main variables that influenced the outcomes of the elections and the entire Iraqi political landscape. These were as follows:

- The outbreak of the October 2019 protests. These popular mass protests spread across all of Iraq’s provinces, especially the southern provinces where Iran’s massive Shiite popular incubators exist. These protests highlighted Iraq’s worsening crises and the popular rejection of external interventions in Iraq’s affairs, especially Iranian interventions. Protesters from all factions, communities, affiliations and regions of Iraq, raised slogans and chants against Iran and its proxies in Iraq such as “Iran out, out….Basra is free, free,” and “Iran out, out…Iraq will remain free.”[2] Protesters set fire to the Iranian consulate in Najaf three times during the protests as well as the Iranian consulate in Karbala which is visited by millions of Shiites annually. They also burnt the Iranian flag in several Iraqi provinces, especially in the Shiite-majority ones.[3] They also pelted shoes at pictures of Iran’s supreme leader and the late Quds Force Commander Qassem Soleimani in several Shiite-majority provinces.[4] The protesters targeted the headquarters of the pro-Iran armed militias in some Iraqi cities. The protesters changed the name of Khomeini Street to 1920 Revolution Martyrs Street.

Social media users in December 2019 launched online campaigns against Iran such as the hashtag “Let it rot” on Facebook and Twitter[5] to boycott Iranian goods which they described as corrupt commodities. They posted photos of the most famous Iranian products distributed in Iraqi markets, calling for these to be boycotted and replaced with Iraqi products.

A young Iraqi man set fire to his Iran-made Saipa vehicle, a move expressing anger and rejection of Iran’s influence in Iraq. Furthermore, video footage that went viral on social media showed a group of protesters dancing over an Iran-made Peugeot car. It was clear that the protesters wanted to destroy the vehicle. The car owner’s reaction was somewhat strange. “This is an Iranian vehicle. I don’t want it anymore,” he said, while laughing.[6] The protests urged the then-prime minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi to tender his resignation in November 2019.

These protests indicated the enormity of Iraqi popular anger and discontent against Iran’s growing clout, represented in the expansive role of Iranian-affiliated armed militias at the expense of Iraqi interests. These demonstrations also reflected the growing awareness and realization of Iraqis about the most urgent dangers facing their country. Iran, therefore, is now facing new challenges regarding the implementation of its cross-border sectarian project in the country which is critical to its regional expansionist project. The attacks mounted by Iran’s proxies against the protestors who rejected Iran’s role in the country had a significant impact on how voters behaved in the recent elections, with Iraqis voting for alliances not backed by Iran. At present, there is great popular pressure regarding the formation of the new government, particularly to designate a new prime minister who meets the demands outlined in the 2019 October protests.

- Electricity is a lever used by the Iranian government against the Iraqi government. The Iranian government has refused to deliver to Iraq its gas share under the pretext of Baghdad not paying its debts. But experts argue that Iran is using the electricity issue as a lever against the Kadhimi government as the latter wants balanced foreign relations and to transition Iraq towards independence and sovereignty. Iran rejects such moves as these will undermine its gains in the Iraqi arena and thwart the implementation of its expansionist schemes. The Iranian gas share to Iraq generates nearly one third of the country’s total electricity production.[7] Hence, Iran’s reduction of gas supplies to Iraq since October 2020 and the total suspension[8] of electricity supply lines on June 29, 2021 are among the reasons behind Iraq’s present electricity crisis. In light of Iraqi awareness about the Iranian role in complicating the electricity crisis, in July 2021 Kadhimi questioned the reasons behind successive Iraqi governments limiting the country’s electricity interconnection to only Iran over the past 17 years while all countries worldwide diversify their electricity supplies.[9] Therefore, his government floated a project to diversify the country’s electricity supply by connecting with the Gulf states, Jordan, and Egypt.

- Iraq turned into an arena for the United States and Iran to settle their scores. Tehran adopted a military approach, waging attacks against US targets in Iraq through its armed militias. Through these attacks, Tehran placed further pressure on Washington to strengthen its negotiating hand and make Washington lift the crippling economic sanctions. The United States, during the Trump administration, adopted a military approach against the deployments of Iran’s militias in Iraq, carrying out several air raids against them in Iraq. In a deterrent message, Washington conducted the most significant air raid when it targeted the former Quds Force Commander Qassem Soleimani, the architect of Iran’s regional project along with Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, former chief of the PMF in January 2020. Iran responded by launching limited and symbolic (nominal) strikes against Ain al-Asad air base. The attacks launched by Iranian militias against US targets in Baghdad and Erbil are continuing during the term of President Joe Biden. The United States has responded by launching military strikes against the positions of Iranian-backed militias in Iraq and Syria.

At the regional level, the 2021 Iraqi elections were held while Saudi Arabia and Iran were holding negotiations on thorny regional issues, especially Iran’s influence in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen. Their fourth round of talks was held in the Iraqi capital Baghdad. The Middle East is also witnessing a new balance of power equation and multiple shifts; Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, Iran’s most important ally, has gained control once again over Syria (Iraq’s neighboring country) through the support offered by Russia and Iran. This has also increased Iran’s interest in Iraq in light of the mounting pressures it faces in Syria from both Israel and Russia. Iran also faces pressures in Lebanon due to consecutive protests rejecting Hezbollah — Iran’s most powerful proxy militia in the region.

The Iraqi elections were held only two months after the ascension of “hardliner” Ebrahim Raisi to the Iranian presidency. Raisi has signaled a greater role for militarization in Iran’s foreign policy and has given more space to Iran-backed militias to implement Tehran’s agenda in its spheres of influence, including Iraq.

Moreover, Iraq’s elections were held against the backdrop of a new US administration led by Joe Biden who took office in January 2021. It has adopted a diplomatic approach towards Iran to urge it to revise the nuclear deal, though it has applied limited military force on some occasions against the positions of Iran’s militias in Iraq and Syria. The Vienna talks on the nuclear deal remain stalled. These talks come at a time when Iran is seeking to move ahead with the arms deals signed with the Russians following the UN’s lifting of the arms embargo on Tehran which expired in October 2020. Hence, Iran could now modernize its military hardware and conclude more arms deals, whether for itself, or for its armed militias or allies in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. This will make Iran’s proxies very strong actors in the internal equations within Tehran’s spheres of influence.

The environment of the Iraqi parliamentary elections reflected the ongoing Iranian role on the Iraqi electoral landscape to create loyalist electoral alliances — to allow them to form the biggest bloc to name a new prime minister who is in harmony with Tehran’s objectives and regional schemes. Given the accumulating internal and external challenges regarding Iran’s influence in Iraq, Tehran does not have the luxury of time to accept any decline in its clout in Iraq; an integral country in its strategy given its geographic, economic, and cultural and security significance.

2. The Contesting Alliances and Forces

There are two major ethnic groups in Iraq: Arabs and Kurds, plus a small minority of Shabaks and Turkmen who make up 5 percent of the population. Regarding sects, Iraq is divided into two main religious groups: Muslims and Christians. Muslims, who represent the vast majority of the population, are divided into two sects: Shiites and Sunnis. The Shiites are mostly Arabs, although there are some other Shiites of non-Arab and Kurdish origin. Most Shiites are concentrated in Iraq’s southern provinces: Najaf, Karbala, Dhi Qar, Basra, Babylon, Wasset, al-Qadissiyah, Maysan and Muthanna. The Sunnis are concentrated to the north and west of Baghdad in Anbar, Sulaymaniyah, Nineveh, Diyala, Erbil, Salah al-Din, Kirkuk and Duhouk. Baghdad has a mix of Sunnis and Shiites. There are a small number of Christians and adherents of other faiths such as the Sabians in Baghdad who account for no more than 2 percent of the population.

Nearly 44 electoral alliances participated in the parliamentary elections. They included an array of political parties and entities — along with independent candidates — to elect 329 Iraqi lawmakers in accordance with the new election law[10] based on the Non-Single Transferable Vote (SNTV) system. According to this law, votes cast go directly to the candidate. Whoever wins the largest number of votes is declared the winner — unlike the old law which was based on a proportional electoral system, with voters voting for electoral lists. The following were the major electoral alliances competing for the biggest bloc in the new Iraqi Parliament:

2.1 Shiite Alliances

The Shiite factions competed in the parliamentary elections through multiple alliances, with some adopting deeply sectarian stances while others were cross-sectarian.

The Sadrist bloc: It is led by the head of the Sadrist Movement, Moqtada al-Sadr. The bloc included candidates only connected to the Sadrist Movement and fielded 95 candidates in the elections.

The Fatah Alliance:It is chaired by Hadi al-Ameri, secretary general of the Badr Organization who is close to Iran. Along with the Badr Organization, the alliance includes the political wings of some of pro-Iran militias such as the Sadiqoun bloc chaired by Qais al-Khazali who is the secretary general of Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, and the Jihad and Construction Movement chaired by Hassan al-Sari who is a leader within the Iran-backed PMF. The alliance also consists of the Sanad bloc chaired by the PMF leader and former lawmaker Ahmed al-Asadi, the Supreme Islamic Council headed by the former lawmaker Hammam Hamoudi and candidates linked to the Sayyid al-Shuhada Brigades chaired by Hashem al-Walaei. The alliance fielded 73 candidates in the elections.

The Harakat Hoquq (the Rights Movement): It is led by the spokesman of Kata’ib Hezbollah (Hezbollah Brigades), Iran’s most powerful ally in Iraq, Hussein Moanes (Abu Ali al-Askari). He resigned from the party in July 2021 and then announced the creation of the movement. The movement is the political wing of the Hezbollah Brigades. The movement’s goals include securing Iran’s objectives in Iraq, especially expelling US forces from the country. The bloc fielded 32 candidates in the elections.

Dawlat al-Qanoon (State of Law Coalition): It is headed by former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, who has close ties with Iran. The coalition includes other parties such as the Islamic Dawa Party, the Islamic Union of Iraqi Turkmen (Shiite), the Eradaa Movement, the al-Bashaer Youth Movement, the Together for Law Movement, and the Bedaya Movement (Beginning Movement). The alliance fielded 72 candidates in the elections.

The National State Forces Alliance: It is led by the head of the National Wisdom Movement Ammar al-Hakim. It includes the Victory Reform Alliance headed by former Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, and the National Conference Movement, as well as the al-Med al-Iraqi and Wataneyoun Movement. The alliance fielded 78 candidates in the elections.

The National Contract Alliance: It is led by the head of the Iran-backed PMF Falih al-Fayyadh. It consists of a number of groups, parties and movements such as the Ataa Movement, Harakat al-Hazm al-Watani, al-Thabat al-Iraqi Party, Warthon Islamic Party, the National Reform Movement and Tajamo’ Rijal al-Iraq. The alliance fielded 80 candidates in the elections.

2.2 Sunni Alliances

In the context of Iraq’s demographic makeup, the Sunnis are second to the Shiites. The Sunnis have ruled Iraq since the late 1960s until the early 2000s. The Shiites took over power in the country following the US invasion in 2003 that toppled Saddam Hussein’s regime. The following are the major Sunni alliances that participated in the 2021 elections:

- The Azm Alliance: It is led by the business tycoon Khamis al-Khinjar. Along with the Arab Project Party led by Khinjar, the alliance includes a host of other political parties such as the al-Wafaa Party chaired by former Electricity Minister Qassem al-Fahdawi; the al-Hal Party led by Jamal al-Karbouli, who is detained in Iraq on corruption charges; the al-Tasadi Party; Civil Track Party; al-Majid al-Iraqi Party; the Civil Society for Reform; and the Free Iraqi bloc along with heavyweight Iraqi figures such as Khalid al-Obeidi and Salim al-Jabouri. The alliance fielded 123 candidates in the elections.

- The National Progress Alliance (Front): It is headed by Iraqi Parliament Speaker Mohammed al-Halbousi. Along with the Progress Party chaired by Halbousi, the alliance includes the National Right Party; the Arab Choice Party; the Moqtadiron for Peace and Building; the Cooperation Society; the Tajammo’ Nahdaht Jeel; the National Initiative (al-Mubadara al-Wataniyah); and the Construction Party (Hezb al-Bena’a). The alliance fielded nearly 105 candidates in the elections.

- The Iraqi National Project Alliance: It is led by the Iraqi businessman Jamal al-Dari. The alliance includes a host of Iraqi opponents who called for an international conference on Iraq to be held in order to address the internal crises.

- The National Front for the Salvation: It is led by former Iraqi Parliament Speaker Osama al-Nujaifi.

2.3 Kurdish Alliances

The Kurds represent the third-biggest ethnic group in Iraqi society. As a result, they play an important role in designating the prime minister. The Kurdish alliances contested the parliamentary elections in Kurdistan with 146 candidates running for 46 seats. The following Kurdish alliances partook in the elections:

- The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP): It is chaired by the former President of Kurdistan Masoud Barzani. Its electoral list was limited to members of the KDP. It contested the elections with 55 candidates in 11 provinces inside and outside Kurdistan.

- The Kurdistan Alliance: It is headed by Lahur Sheikh Jangi — co-president of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan, the second-biggest Kurdish party in Iraq, along with Bafel Talabani. The alliance also includes other Kurdish parties and movements such as the Turkmen Justice Party; the Decision Party; the Will Party; the Turkmeneli Party; the Civilian Right Party; the Change Movement; the Turkmen Nationalist Movement; the Turkmen Wafa Movement; and the Turkmen-Iraqi Front. The alliance fielded 42 candidates in the elections. However, there were Kurdish parties that decided to contest the elections individually without joining this alliance such as the New Generation Movement; the Kurdistan Justice Group; and the Kurdistan Toilers’ Party.

2.4 Boycotters of the Elections

Several new parties and movements – born out of the protest wave known as the Tishreen (October) movement — along with some old alliances and parties such as the al- Wataniyah Alliance headed by the former prime minister and president of the Iraqi National Accord Party Ayad Allawi; and the Civil Democratic Alliance led by Ali al-Rafei. It also includes the Iraqi Communist Party; the Basma National Party; and the Social Democratic Movement.

It seems that there were a host of reasons behind the boycotting of the elections, such as not holding to account those who killed protesters, ongoing rampant corruption, failure to address deep crises such as the electricity, water, and unemployment crises. In addition, the Iraqi state has been unable to limit weapons to the state.

A political reading of the map of electoral alliances for the 2021 parliamentary elections reveals four main characteristics:

- The ongoing divisions amongst the electoral alliances on sectarian and ethnic lines as was the case in the 2018 elections.

- The divisions have seeped into the ethnic and sectarian factions themselves. The Shiite alliances splintered into more than five Shiite alliances, while the Sunnis into four major alliances. The most salient division during the 2021 elections was the division between the Qom and Najaf loyalists. The divisions between the pro-Iran political wings were also apparent, reflected in the differences existing amongst the pro-Iran armed militias in Iraq. Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq and Kata’ib Hezbollah, the political wings of the two biggest pro-Velayat-e Faqih competing militias, contested the elections under two different alliances. The political wing of Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq contested the elections under the Fatah Alliance headed by Hadi al-Ameri, while the political wing of Kata’ib Hezbollah contested the elections under Harakat Hoquq.

- Compared to the 2018 elections, the number of deeply sectarian electoral alliances in the 2021 elections increased. Kata’ib Hezbollah, Iran’s most powerful ally in Iraq, established a political wing to run in the elections headed by Abu Ali al-Askari. Falih al-Fayyadh, backed by Iran, established the National Contract Alliance to run in the elections. On the other side, the number of cross-sectarian alliances decreased. The cross-sectarian Sairoon Alliance, which appeared in the 2018 elections, fragmented. The Sadrist Movement, which made up the biggest bloc amongst the alliances, contested the elections alone without joining other Shiite alliances. Yet, the National Wisdom Movement Alliance and the Victory Alliance, which won advanced positions in the 2018 elections, merged and formed a new alliance called the National State Forces Alliance led by Ammar al-Hakim.

- The Shiite alliances contesting the elections increased as opposed to the Sunnis. There were six Shiite alliances, including deeply sectarian ones, that contested the elections while some new Sunni alliances and some Sunni parties had insignificant influence in the Iraqi equation.

The aforementioned factors led to votes being scattered among different ethnic and sectarian alliances. This perpetuated the inherent problem in all elections – the inability of a single alliance to form a new government on its own. Due to this problem, multiple scenarios arise over forming the next government and choosing the next prime minister. The political factions usually settle on a consensual candidate to form the next government. An alliance should win the majority of seats — 165 seats — to form the next government on its own.

The growing divisions between Iran-backed political and military parties are related to the death of Qassem Soleimani and Iran’s declining financial and logistical support to them. In addition, Iran’s spheres of influence have been shrinking and US airstrikes targeting militia sites have contributed to the widening divisions between them. These divisions are related to the competition between the Najaf and Qom marjayas. Ayatollah Sistani rejects Iran’s control over Iraqi affairs. He believes Iran is attempting to diminish Najaf’s influence in favor of Qom —especially as there is a historic difference between the Najaf and Qom marjayas over the theory of Velayat-e Faqih. The Najaf marjaya rejects the theory of Velayat-e Faqih, calls for religion to be separated from the state and supports the establishment of a civil state.[11] Hence, Shiite alliances were divided into two camps:

- Supporters of the Qom Marjaya: They included the Fatah Alliance; Harakat Hoquq; and the State of Law Coalition, which received huge support from Iran. This support was a bone of contention between Qom and Najaf, as the latter rejected it. The mass protests staged in Iraq, especially in the Shiite-majority southern provinces, reflected the plummeting popularity of the Iranian political system in general and Khamenei in particular among Iraqi Shiites.

- Supporters of the Najaf Marjaya: Najaf has rejected Iranian attempts to wrestle control over Iraq’s internal and external decision-making and is against weapons outside state control. This means it has a desire to support the transition to statehood based on total sovereignty and independence. The Sadrist bloc and some aligned with the Islamic Dawa Party support Najaf’s aims. Sistani wields massive influence in Iraq, as thousands of Iraqis heeded his call to take up arms against ISIS following his religious decree regarding the “individual obligation of jihad” in June 2014. There was also heavy turnout by Iraqis in the 2005 elections following his call to cast votes and vote on the Constitution. In contrast, in late September 2021, his call for Iraqis to vote in the 2021 parliamentary elections had little impact in light of the apparent increase in apathy among the people.

Iran has ramped up pressure before the parliamentary elections in Iraq since 2003 to boost the chances of its aligned factions winning and naming the next prime minister. This has enabled Iran to implement its schemes and achieve its ambitions since the Iraqi political system is parliamentarian in nature according to the Iraqi Constitution approved in 2005. Under the Constitution, the prime ministerial post holds extensive executive powers and purviews.[12] He is the top executive official, who responsible for the state’s general policy and is the commander-in-chief of Iraq’s armed forces. He has the right to sack ministers upon approval from the Parliament. The Parliament approves the names of those nominated by the prime minister for the following posts: ambassador, chief of staff, intelligence and security chiefs. He also negotiates and signs international treaties and agreements and proposes bills. Hence, Iran is keen on naming an Iraqi prime minister who is loyal to Tehran.

3. Electoral Issues and Programs

The electoral programs of the alliances competing to win the most seats in the 2021 elections included a number of issues linked to the current phase. These issues were not very different from those that dominated the 2018 parliamentary elections such as corruption and Iraq’s identity and future. These issues had a major impact on the elections results. The most prominent electoral issues for this year’s elections were as follows:

3.1 Addressing Deteriorating Services and Combating Unemployment and Poverty

Most of the alliances addressed the consequences of the electricity outage crisis, how to address it and ways to counter corruption. Leaving the electricity crises unaddressed has been the biggest challenge facing successive Iraqi governments, as the crisis led to the massive protests in which people took to the streets and toppled former governments such as that of former Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi. It will remain a huge challenge facing the new government due to the lack of resolve to address its root causes. Iran’s refusal to deliver Iraq’s share of electricity to the country is considered among the multiple levers used by Tehran against the Iraqi government to impede its transition to statehood based on independence and sovereignty — the lack of these two critical elements have perpetuated the electricity crisis in Iraq.

Corruption also played a central role in the programs of the electoral alliances contesting the elections. In 2020, Iraq’s low ranking on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index was a cause for concern. It ranked 160 out of 180 countries.[13]

Corruption led to approximately twice the value of Iraq’s gross domestic product (GDP) vanishing since 2003. The Iraqi Commission of Integrity set up to fight corruption after Prime Minister Kadhimi assumed power has estimated that nearly $500 billion vanished over 17 years through the signing of fictional contracts. The commission stated that that it recovered approximately $3 billion embezzled over the past two years alone after it had been invested in real estate purchased in London.[14] Fighting corruption is a key priority for Iraqis as it has turned Iraq, which possesses massive oil resources, into an impoverished state incapable of meeting public needs. Corruption has also led to a shortage in public services such as electricity, water, health and education. These shortages led the Iraqi people to take to the streets in large numbers.

Iraqi columnist Muthanna al-Jadergi said, “Corruption’s normality and extensive nature in Iraq is due to different reasons, maybe the most important and dangerous is the role of the Iranian regime — which wields the biggest and worst influence over Iraq.”

He added, “For this regime to ensure its survival and the continuation of its clout in an important and strategic country like Iraq, it must remove the personalities with patriotic sentiments and orientations from leadership positions. It must make these people submit to its surrogates and not defy its orders.” Jadergi indicated that fighting corruption, totally eliminating it, and removing the impact of its far-reaching damage on the Iraqi people, begins with countering the clout of the Iranian government.[15]

3.2 Iraq’s Independence and Sovereignty

The electoral programs of some alliances such as the Sadr Alliance, the Victory Alliance, the Wisdom Alliance and others backing the Najaf Marjaya prioritized Iraq’s sovereignty and independence. Hence, these programs centered on the necessity of Iraq restoring its leading position, sovereignty, and independence through transitioning to the phase of statehood and returning to the Arab fold. In addition, priority was accorded to banning weapons outside state control, curbing the clout of pro-Iran armed militias deployed across Iraq and halting foreign interference, particularly from the United States and Iran. Meanwhile, the programs of other alliances such as the Fatah Alliance, the State of Law Coalition and others who back the Qom Marjaya remained heedless of Iraq’s sovereignty and independence. These alliances stuck to the “non-state” approach by approving weapons outside state control. This issue was critical when it came to casting votes or abstaining from voting for certain electoral alliances.

3.3 Establishing Balanced Foreign Relations

The programs of the cross-sectarian electoral alliances struck a balance in foreign relations by calling for Iraq to return to its Arab fold and to break away from its submission to Iran and its proxies which has harmed Iraq’s historic stature and position. Iran’s interference in Iraq has led the country to be amongst the most crisis-ridden states — despite its massive oil resources. Nonetheless, the programs of some sectarian pro-Iran alliances such as the Fatah Alliance and the State of Law Coalition focused on keeping Iraq within Iran’s sphere of influence. Establishing balanced foreign relations was a focal point prompting Iraqi voters to cast votes for electoral alliances prioritizing Iraq’s Arab dimension in their electoral platforms. Many voters looked to Iraq as a state with a civilization that is authentic, lofty and deep-rooted.

4. Election Results and Alliance Quotas

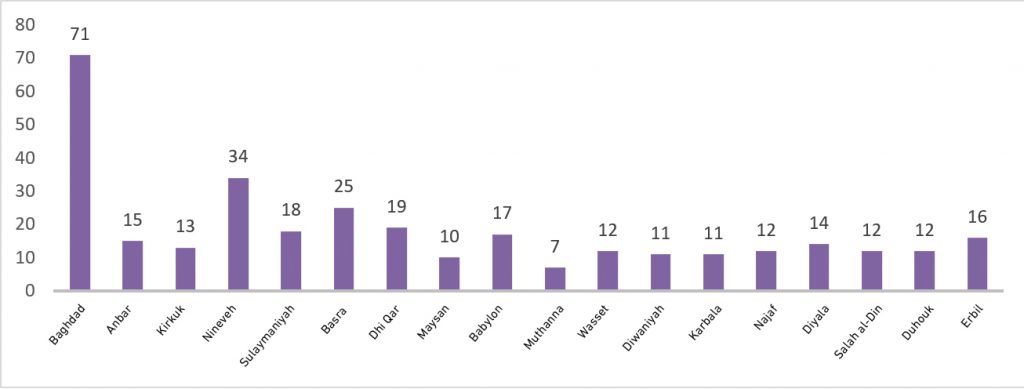

The Iraqi Parliament comprises 329 seats. According to the new Law No. 9 of 2020 concerning the election of parliamentary representatives, the seats were distributed across 18 Iraqi governorates based on the population of each governorate as illustrated in Figure 1. The seats were divided into 237 regular seats, 83 quota seats, 74 seats for women and nine seats for minorities: five for the Christians in Baghdad, Nineveh, Kirkuk, Dohuk and Erbil, one seat for the Feyli Kurds[16]* in Wasit, one seat for the Shabaks in Nineveh, one seat for the Yazidis in Nineveh, and one seat for the Sabians in Baghdad.[17] The number of seats allocated to Sunnis and Shiites totaled 320.

Figure 1: The Distribution of Parliamentary Seats Across the Various Iraqi Governorates

Source: Prepared by the Research and Studies Center, the International Institute for Iranian Studies, based on the data of Iraq’s Independent High Electoral Commission and the briefing about the distribution of seats for the 2021 Iraqi parliamentary elections, accessed October 11, 2021, https://bit.ly/3anJsg9.

According to the official website of Iraq’s Independent High Electoral Commission, the distribution of seats for the electoral coalitions in Iraq’s 2021 Parliament were as follows:

First Rank: The Sadrist bloc: It came first with 73 seats (22 percent) out of 329 seats in the Iraqi Parliament, with 19 seats ahead of the Sairoon Coalition, which came first in the 2018 elections with 54 seats. Thus, Sadr will be in a strong position in the negotiations regarding who will take over the highest executive position in the country.[18] The Sadrist bloc coming first was because of the characteristics related to its electoral program, such as the following:

- Cross-sectarian: The Sadrist bloc is the most important, popular and powerful Shiite force in Iraq for several reasons: it met the demands of the protesters who rejected the quota system, committed itself to national interests, rejected sectarianism, and called for Iraqi sovereignty to be safeguarded in accordance with Iraqi identity. In addition, it called for the end of foreign interference, weapons to be limited to the state and army, rejected the hegemony of the Qom Marjaya in regard to Iraqi decision-making, and demanded that Iraq return to its natural Arab surroundings.

The aforementioned was reiterated in Sadr’s speech after the preliminary results were announced. He described the victory of his bloc as a victory for reform. He said, “It is the day of the victory of reform over corruption, and the day of the people’s victory over occupation, militias, poverty, injustice and slavery. It is the day on which sectarianism, ethnicity and partisanship were removed to open the gates of Iraq. For Iraqis, there is no difference between any of them and we are their servants.” He added, “It is the day of the oppressed minorities, and the day of the deprived Shiite, the day of the oppressed Sunni, and the day of the concerned Kurd.” In a message to the international community he said, “All embassies are welcome as long as they do not interfere in Iraqi affairs and the formation of the government. If there is any intervention, we will have a diplomatic response or perhaps a popular response befitting the offence. Iraq is for Iraqis only, and we will allow no intervention at all. From now on, arms must be limited to the state, and they must not be used beyond its writ. People have the right to live without occupation, terrorism, or militias that kidnap, intimidate, and negatively impact the prestige of the state. Iraq is the place of the marjaya, wise people, and dignitaries.”[19] It is obvious that Sadr is committed to limiting weapons to the state, rejects foreign interference, including Iranian interventions, and intends for Iraq to regain its independence and sovereignty.

- Understanding the concerns of the Iraqi people: In its program, the Sadrist bloc prioritized countering corruption and the crises facing the Iraqi people. It emphasized that it will prioritize solving the electricity, unemployment and water crises. This is in order to raise the standard of living of the Iraqi people in accordance with the country’s resources, history and civilization. Its supporters have in the past chanted slogans against Iran, its armed militias and corruption in Iraq, stressing the need for independent decision-making in Iraq.[20]

- Sadr’s good relations internally and externally: Sadr has good relations internally with many Sunni and Kurdish coalitions such as with the Kurdistan Democratic Party, as well as cordial relations with communists and secularists owing to his loyalists supporting them in the protests that followed the 2018 parliamentary elections against corruption. He has good relations externally with many Gulf and Arab countries that welcome Iraq returning to its Arab fold. Sadr is palatable to the West and America for two main reasons. First, he emphasizes the independence of Iraqi decision-making and opposes Iranian hegemony. Secondly, he is open to Washington’s regional allies, especially Saudi Arabia, because of his intention to return Iraq to its Arab environment.

Second Rank: Unlike the 2018 elections, in which Sunni alliances were at the lower end of the rankings, the National Progressive Coalition, one of the most prominent Sunni alliances through which the Sunni forces contested the 2021 parliamentary elections, made very significant progress, by displacing the Iran-backed Fatah Alliance which came second in the 2018 elections. It won 38 seats in the 2021 elections. This success reflects the confidence of Sunni voters in their leaders once again, and their awareness about the importance of casting their votes to compete against other parties and achieve some balance of power with the Shiite alliances – especially after Sunni quotas declined during the past electoral cycles since the Shiites controlled the government and adopted a policy of elimination and displacement against the Sunni community. This policy was in line with Iran’s policy to influence the outcome of the elections in favor of Shiite alliances.[21] Furthermore, the poor turnout in the past reflected the Sunnis’ lack of confidence in the nominated Sunni leaders.

Third Rank: The State of Law Alliance which has close relations with Iran, fared better in the 2021 election compared to the 2018 elections when it came fourth with 26 seats. It ranked third in the 2021 parliamentary elections with 37 seats, indicating the coalition’s ability to mobilize people during the elections.

Fourth Rank: The Kurdistan Democratic Party won 25 seats in the 2018 parliamentary elections, but this time fared better as well, ranking fourth with 32 seats. This means it won seven more seats in the 2021 elections. This indicates that Iraqis voted for the coalition because it apparently supports the country’s transition to statehood and intends to meet protester demands from October 2019.

Fifth Rank: The Iran-backed Fatah Alliance dropped significantly in the rankings. It fell from second position in the 2018 parliamentary elections when it won 47 seats to fifth position in the 2021 parliamentary elections when it won only 14 seats, a loss of 33 seats. The result indicates its deep regression in Iraqi political life. This regression may be because of Iraqis realizing the danger posed to the future of the country by Iran-backed Shiite alliances. Iraqis themselves can sense the net results of Iran’s influence in the country over the last decade and a half. Economic conditions have declined; political life has deteriorated; the Iraqi people are divided across sectarian lines; economic, security and political problems have accumulated, and the country has turned into an arena where international actors settle their scores.

The Shiite forces in general and the Fatah Alliance (the closest ally to Iran) in particular suffered a resounding defeat in the 2021 elections. Therefore, it was not surprising that the Shiite Coordination Framework (a group including armed Shiite parties and forces, mostly from the Fatah Alliance) announced in a joint statement their total rejection of the preliminary results of the early elections. Fatah Alliance leader Abu Mithaq al-Masari confirmed that the alliance faced great injustices during the elections.[22] The Shiite Coordination Framework held the Electoral Commission “fully responsible for the failure of the electoral process and its mismanagement, which will negatively impact the path towards democracy and societal reconciliation.”[23] By not recognizing the election results, the Shiite alliances intend to pressure the winning alliances into making concessions in their favor when it comes to the negotiations regarding government formation and designating a new prime minister. The winning alliances will be in a tight corner if they want to avoid Iraq slipping into a new cycle of violence or another extended political crisis.

The Lower Ranks: The Patriotic Union of Kurdistan took sixth place with 15 seats, the Azm Alliance ranked seventh with 14 seats, and the New Generation Movement took eighth place with nine seats. The State Forces Alliance’s loss, which surprised political circles at home and abroad, was unexpected and resounding. This alliance includes both the National Wisdom Movement led by Ammar al-Hakim and the Victory Alliance led by Haider al-Abadi. The Victory Alliance was ranked third in the 2018 elections after the Sairoon Alliance and the Fatah Alliance. The Victory Alliance won 42 seats, and the Wisdom Movement won 20 seats in the 2018 elections. However, the two alliances scored only four seats in the 2021 elections.[24] This means that they lost about 58 seats out of the total number of their 62 seats in the 2018 parliamentary elections. The PUK lost some seats.

5. The Implications of the Shift in Iraq’s Electoral Scene

Based on the election results and the seats won by the Shiite, Sunni and Kurdish alliances in the 2021 parliamentary elections, the following conclusions can be drawn:

5.1 The Dilemma of the Largest Bloc

The election results indicate that no one alliance won an absolute majority of seats (165 seats) to form the new Iraqi government. Therefore, the likely scenario is that some alliances will arrive at a consensual position when it comes to forming the next Iraqi government.

5.2 The Shift in the Awareness of the Iraqi Voter

There is growing Iraqi awareness, evident since the 2018 elections, of Iraq’s rich history and civilization and its natural affiliation with its Arab fold. Moreover, Iraqis have realized the danger of sectarian alliances reflected in their support for the cross-sectarian Sairoon Alliance in 2018. Iraqi voters were even more aware during the 2021 elections, as they dealt a resounding blow to the Shiite alliances with sectarian inclinations. They did not vote for them except for the State of Law Coalition. The Fatah Alliance fell to fifth place after it held second place in the 2018 elections, and the Victory and Wisdom alliances also fell significantly behind by winning only four seats. They collectively lost 58 seats when compared to their seats in the 2018 Parliament.

5.3 Iran’s Grave Miscalculation of Iraqi Voter Perceptions

Iraqi citizens have played a significant role in the country’s political and electoral processes, particularly during the past five years, and thwarted former Iraqi Prime Minister Dr. Haider al-Abadi’s plan to secure a new term after the 2018 elections via launching mass protests, and overthrew the government of Adil Abdul-Mahdi in November 2019 during the October 2019 protests. The protesters forced the Iraqi state to hold early parliamentary elections, shifting them from 2022 to October 2021 and strengthened the current Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi’s hand to form a political program and supported his quest to transition Iraq to a phase of statehood and independence and to bring the country back to its Arab fold despite Iran’s dislike of this transition. Iraqi citizens, especially the youth, do not accept the ideological dictates of clerics anymore; they have become more open to the world and look to the successful experiences of other countries, and they aspire for freedom, human rights and fighting corruption in their country. This is a significant development and should be invested in and relied upon against Iran’s project in the Arab region because the younger generation has no interest in it. Iran has misread the intellectual transformation that has taken place among the youth, as reflected in the 2021 election results. Iraqi voters dealt a serious a blow to Iran-backed Shiite alliances. They voted for the cross-sectarian Sadrist bloc which has spoken about their concerns, issues, and promised to meet protester demands.

5.4 Lack of Voter Confidence in Traditional Institutions

There was a decline in voter turnout from 44.5 percent in the 2018 elections to 43 percent in the 2021 elections. According to the Independent High Electoral Commission’s statistics, 9.6 million voters out of 22.1 million eligible voters cast their ballots, reflecting the ongoing crisis of voter confidence in the electoral process — as well as the dissatisfaction with the political and legislative processes felt by citizens and protesters who participated in the protest movement that overthrew Abdul-Mahdi’s government. In addition, the low turnout reflects their lack of confidence in the Parliament’s capacity to meet protester demands, especially the prosecution of those who killed protesters and activists and its ability to address serious problems such as the unemployment, electricity and water crises, as well as the rampant corruption crisis existing across all state institutions. Further, the low voter turnout indicates that the Iraqi people are no longer responsive to the calls of politicians and clerics (the Supreme Marjaya in Najaf) to participate in the elections. The 2021 elections witnessed a low voter turnout compared to the high turnout in the 2005 elections in response to the calls of the marjaya and the thousands of Iraqis who responded to its call to fight against ISIS during 2014.

5.5 Growing Divergences Amongst Shiites Parties

The Sadrist bloc secured first place in the early elections as Sadr’s plan to move Iraq to the phase of statehood and independence and return the country to its Arab fold as well as to limit weapons to the state and achieve a sense of balance in foreign relations resonated with the Iraqi people. The Shiite Coordination Framework and the Fatah Alliance, however, rejected the election results entirely. It is expected, therefore, that the divisions between Shiite parties will rise, particularly between those who support the Iranian agenda, such as Shiite alliances with sectarian inclinations, and those who support the path towards statehood and independence, such as the cross-sectarian Shiite alliances. Shiite partisan divisions will deepen further as they work to form the largest bloc to designate a new prime minister. It is true that the divisions between the Shiite alliances are not new, but the results of the recent elections indicate that the divisions will reach new acute levels and will impact the shape of the Iraqi government, its power, its alliances and external relations. The divisions are expected to deepen further after the US withdraws its forces and ends its combat missions in Iraq by the end of December 2021.

5.6 Societal Shift Towards Women’s Participation in the Parliament

In previous parliamentary elections, it was difficult for women to win seats despite the quota allocated to them, but in the 2021 elections, they won 97 seats. Fifty-seven women won by their voting power alone without the need to resort to the quota allocated to them, due to their strong participation in the October 2019 protest movement against the country’s unemployment, electricity and water crisis, and extensive corruption and external interventions. This outcome is a great development in regard to changing Iraqi culture and carving a role out for women in the Parliament alongside men.

5.7 Increasing Opportunities to Secure a Balance in Iraq’s Foreign Relations

For more than a decade and a half since the United States invaded Iraq, the country has depended on Iran and those who support the uncontrolled supply of weapons and the proliferation of non-state actors, thus thwarting its ability to achieve a balance in foreign relations. However, it seems that Iraq is facing a turning point and has an opportunity to achieve a balance in its foreign relations. In the past electoral cycle, Iraqi voters supported the cross-sectarian coalition Sairoon and in this cycle voted for Shiite and Sunni cross-sectarian alliances, and rejected Shiite alliances with sectarian inclinations. This has increased the likelihood of securing a balance in foreign relations. This in turn boosts Iraq’s attempts to return to its Arab fold, and facilitates greater Iraqi, Arab and Gulf coordination on issues of common concern to reduce Iran’s influence in Iraq.

6. The Limits of Iran’s Influence Following the Election Results

The early elections unveil a new Iraqi equation for the next four years. The Iraqi people have realized and rejected Iran’s agenda and its sectarian proxies in their country. They, despite the 2021 low turnout, are still keen to participate in elections. Their votes favored the cross-sectarian Sadrist bloc. The results indicate that the voters avoided the Shiite alliances with sectarian tendencies. This was a severe blow to the Fatah Alliance, Iran’s closest ally in Iraq, foreboding the decline in Iranian influence in Iraq in the future.

In light of the recent electoral results, which reflected the deep losses experienced by Shiite coalitions allied to Iran, it is expected that Iran will be concerned about its influence in Iraq, the most important arena for Tehran’s strategy. Therefore, some media circles revealed a secret visit of the Quds Force Commander Ismail Qaani to Iraq after the preliminary electoral results were announced. This visit was initiated to restore the influence of Iranian-backed alliances in the new government, to ensure Tehran maintains its gains in order to implement its strategy.

Iran understands that the formation of an Iraqi government which is not submissive will transition the country to the phase of statehood and end the role of non-state actors. This means the creation of obstacles in front of the Iranian project in Iraq if the new government pursues the same line as Kadhimi to limit weapons to the state, end sectarianism, establish a balance in its foreign relations and take steps to return the country to its Arab fold. The above is to be achieved by the new government presenting an alternative national project different from Iran’s sectarian project, and promoting the independence of Iraq’s decision-making and ending the influence of Iran-affiliated militias.

To maintain its gains, which it will not give up easily, Iran will use all its cards in Iraq to designate a prime minister who is palatable to it, as witnessed during the process that led to the appointment of Kadhimi as Iraq’s prime minister. Some of its arms may resort to escalation to prove that Iran has influential cards. Iraq is of geopolitical significance for Iran because it is an important link along the Iranian corridor that connects Tehran with the Mediterranean, and it is a main corridor for arms smuggling to its militias in Syria and Lebanon, and an economic outlet to alleviate the impact of US sanctions. Iraq is also ranked second in the Arab world after Saudi Arabia in terms of possessing the largest crude oil reserves. We cannot ignore the proliferation of Shiite shrines in Najaf and Karbala. Iraq has the largest number of Shiite marjayas in the world. Najaf hosts the largest scholarly university for Shiites known as Al Hawza Al-Alamiya. As a result, Iran has continuously attempted to pull the rug from under the feet of the Najaf Marjaya in favor of Qom.

Iran also fully understands that the historic opportunity provided by the United States after its invasion and overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s regime will never occur again, and the emergence of a strong and regionally active Iraq once again in the regional equation will challenge its influence and exacerbate threats on its western borders, especially if a pro-US Iraqi government works to encircle and strangle Iran. On the other hand, the presence of an Iraqi government loyal to Iran ensures Tehran has secure borders on the western side and will help it to extend its sphere of influence. As a result, Iraq will always be of great strategic importance to Iran, which explains Tehran’s rapid extension of influence into Iraq after the US invasion of the country, until it turned into the most prominent player in the Iraqi arena.

Conclusion

The results reveal that Iraq will enter a new stage of political maturity with a completely different political orientation compared to the previous stage. This will include accumulating challenges to Iran’s presence in Iraq as Iraqi voters dealt a major blow to Iran-backed Shiite alliances with sectarian tendencies. The Fatah Alliance, a prominent Iranian ally, lost its strong presence in the new Iraqi Parliament, while cross-sectarian Sunni and Shiite blocs won a remarkable number of seats, heralding their rise.

The results also reveal that there exists a cross-sectarian national Iraqi bloc that is against sectarianism and Iran’s influence within Iraqi institutions. The bloc managed to expose the reality of Iran’s expansionist plans and accordingly delegitimized these. It showed to the Iraqis and the world Iran’s failure in making Iraq – a central country in Iran’s expansionist agenda – a model to be followed by other countries. This bloc will take advantage of the opportunities to transition Iraq to statehood and render Iran’s transnational project a mere delusion. This aim will be helped by the emergence of a younger Iraqi generation which rejects clerics and ideologues. This raises the cost of Iran continuing with the implementation of its regional project. However, establishing a nation state by controlling arms and curbing the influence of militias in Iraq is still fraught with danger due to the escalation of violence by militias which wield immense influence in the Iraqi equation. There are many potential scenarios revolving around electing the new prime minister, however, it is most likely that a larger bloc will be formed which will designate the new prime minister.

Endnotes:

[1] “The House of Representatives Votes on Bill Integrating the Popular Mobilization Forces Into the Army and Begins Reading the Bill Regulating the Commercial Agency,” The Iraqi House of Representatives, November 26, 2016, accessed October 21, 2021, https://bit.ly/3n74K7q . [Arabic.

[2] “Iraq’s Demonstrations Chant: Baghdad Is Free, Free .. Iran…Out, Out,” YouTube, October 4, 2019, accessed October 21, 2021, https://bit.ly/3naWCDb [Arabic].

[3] “Iraqi Tweet: Shovels That Destroy the Idol Khamenei on Twitter,” al-Arab, October 8, 2019, accessed October 21, 2021, https://bit.ly/3vufFfk [Arabic].

[4] “Pictures of Soleimani and Khamenei Under the Shoes of Iraqi Demonstrators,” YouTube, November 3, 2019, accessed October 21, 2021, https://bit.ly/3m13gMJ [Arabic].

[5] Hashtag on Facebook, #Let it_Rot, December 13, 2019, accessed October 21, 2021, https://bit.ly/3aTQdqh, and hashtag on Twitter #Let_it_Rot December 10, accessed 21 October 2021, https://bit.ly/3G3m4D8 [Arabic].

[6] “Hostile Chants, and the Burning of Consulates… Why Did the Iraqis’ Anger Increase Against Iran?” al-Istiqlal, December 08, 2019, accessed October 21, 2021, https://bit.ly/3aURQnl. [Arabic].

[7] “Electricity of Iraq: What Is the Iranian Dimension in the Electricity Crisis That Iraq Is Experiencing?” July 2, 2021, BBC Arabic, accessed October 20, 2021, https://bbc.in/3E2iPtK. [Arabic].

[8] Joe Snell, “Intel: Iraq’s Power Crisis Prompts Resignation of Electricity Minister,” al-Monitor, June 30, 2021, accessed January 20, 2021, https://bit.ly/3lZujIg

[9] “Years of Failure… Questions Emerge About the “Electrical Interconnection” for Iraq,” Sky News, July 4, 2021, accessed October 19, 2021, https://bit.ly/3G6rGMO. [Arabic].

[10] For more on the new Iraqi electoral law for 2020, see the official website of the Iraqi House of Representatives, the Iraqi Parliament Election Law, accessed October 20, 2021, https://bit.ly/2Z72vcf. [Arabic].

[11] Mustafa Habib, “They Disagree About the Idea of Wilayat al-Faqih: Al-Sistani and Khamenei… a Historical Conflict Being Rekindled in a Political Way,” Iraq.net, September 4, 2015, accessed October 20, 2021, http://cutt.us/KLA2 . [Arabic].

[12] For more information about the powers and prerogatives of the Iraqi prime minister, the full text of the Iraqi Constitution can be seen, the Constitution of the Republic of Iraq 2005, accessed October 20, 2021, https://bit.ly/3n7KhPS. [Arabic].

[13] “Iraq in the Corruption Perceptions Index 2020,” Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index 2020, accessed October 20, 2021, https://bit.ly/3G0tRl4. [Arabic].

[14] “Mediapart: Iraq Has Been Plagued by Corruption for 18 Years, and the People Are the Victims,” Al Jazeera, February 17 , 2021, accessed October 20, 2021, https://bit.ly/3lYu6VY

[15] Muthana al-Jaderji, “The Fake War on Corruption in Iraq,” Kitab, March 27, 2021, accessed October 20, 2021, https://bit.ly/2Z7xJQv.

[16] * Feyli Kurds are Shiites and speak a Kurdish dialect which is different from the Kurds in Iraqi Kurdistan.

[17] “The Independent High Electoral Commission, Distribution of Seats of the 2021 Iraqi Parliamentary Elections,” accessed October 11, 2021, https://bit.ly/3anJsg9

[18] “In Regard to the Primary Election Results: the Sadrist Bloc Is in the Lead and Al-Fatah Alliance Falls Behind,” Alsumaria, October 12, 2021, accessed October 20, 2021, https://bit.ly/2XBIv0M. [Arabic].

[19] “The Full Text of the Speech of His Eminence the Leader, Muqtada al-Sadr Delivered to the Iraqi People After the Announcement of the Results of the Parliamentary Elections on October 11, 2021,” The Private Office of His Eminence Sayyid Muqtada al-Sadr, October 13, 2021, accessed October 20, 2021, https://bit.ly/3niqLAx. [Arabic].

[20] “Al-Sadr Makes Progress in the Elections and His Supporters Chant Iran’s Departure,” Iraqi al-Yaum, May 15, 2018, accessed October 20, 2021, http://cutt.us/YKTUc. [Arabic].

[21] “Fixed and Variable in the Equations of the Iraqi Elections,” Deutsche Welle, January 20, 2021, accessed October 20, 2021, https://bit.ly/3vFdwg. [Arabic].

[22] “The Leader of the Al-Fatah Alliance Abu Mithaq Al-Masari: There Is a Great Injustice Against Our Alliance in the Elections,” Al-Fallujah Channel, October 13, 2021, accessed October 20, 2021, https://bit.ly/3npkdjB. [Arabic].

[23] “After Today’s Meeting, the Shiite Coordination Framework Takes One Decision,” Shafaq News, October 20, 2021, accessed https://bit.ly/3D9N7el. [Arabic].

[24] “In Regard to the Results of the Primary Elections: the Sadrist Bloc Is in the Lead and the Al-Fatah Coalition Falls Behind,” Alsumaria, October 12, 2021, 2021, accessed October 20, 2021, https://bit.ly/3C97esq. [Arabic].